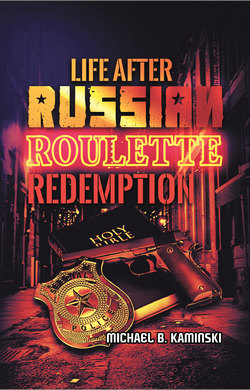

Читать книгу LIFE AFTER RUSSIAN ROULETTE: REDEMPTION - Michael Kaminski - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 4: THE LAW OF THE WEST

ОглавлениеThe first couple weeks were basically orientation into the environment of Western. Not only foot patrol assignments but, maybe more important, the unofficial and unwritten policies and procedures of policing the district.

I was assigned to sections of Pennsylvania Avenue and West North Avenue. As I walked and patrolled the blocks of Pennsylvania Avenue and looked at the buildings, I wondered why it was called "The Street of Dreams". It would not be long before reality in Western would come to light when the call came out for a possible jumper.

“Man on a roof threatening to jump,” the steady voice of the dispatcher advised. “Any units in the area of the 500 block of Cumberland Street respond.”

Being a rookie, the next call was always anticipated with some degree of anxiety, especially when you walked the post alone. Somehow, this one was different. It was not on my post but I was close enough to respond.

On foot patrol, your response time is only as quick as you can run. By the time I reached the 500 block of Cumberland Street, the sector patrol cars already arrived on the scene and a crowd gathered. It was a valid call. A man on the roof of a row house threatened to jump. As I watched, I could not imagine getting to a point in my life where I would have the courage, or lack of desire of life, or weakness to actually attempt suicide. Later in life, I would understand this man’s wish to want to end it all.

I was assigned to crowd control along with some of the other members of my squad who responded. As the supervisors in charge of the scene tried to talk with the man, the situation intensified as the crowd became more involved. The night was bitter cold and emotions were high as the man continued to yell and threaten to jump.

At some point, one of the police officers yelled, “If you are going to jump, then jump, it is cold out here.”

The man jumped and fell to the ground, dead. Suddenly there was deathly silence. Eventually the crowd dispersed and Sergeant Florey advised his squad to go back into service. I walked back to my foot post partially thinking about the outcome of the situation but also listening for the noises in the night. You can never be too relaxed after a situation like that when you wear a blue target.

After shift, we all gathered in the parking lot of Western, as usual, and discussed the events in the way we did most nights. We drank beer and talked about the calls. This was an unusually eventful shift. After our unofficial staff meeting and processing what happened, we threw the empty beer cans in the back of the Lieutenant’s pick-up truck and went home. After all, there was a law against littering. Who else could we talk to that would understand? How can you go home and tell your wife everything you did when she asks, “How was your night?”

I dressed to kill every shift. I always carried my custom made lead lined nightstick that came to a point. I carried a lead lined “slap jack” in my back pocket. A two-inch snub nose revolver was strapped to my right leg. And on my left leg I attached a razor sharp knife designed to fillet fish.

January and February in Western remained very quiet. We had our routine response calls to bar fights and domestic calls but nothing serious. During our informal staff meetings after shift, we continued to discuss the calls of the night over a couple cases of beer. We all agreed that bar fights were a lot safer than domestic disturbance calls. At least, on a bar fight call you know what you are walking into. Domestic disturbances can go either way and you do not know who is going to turn on you, especially the woman. Nobody really got drunk because it was always too cold to have long shift parties. Besides, who was going to arrest us? We were the police.

The different dynamics of our two squad leaders was an interesting study in police personalities. Sergeant Tim Florey was a very sensitive and gentle man. He really cared about his men. Glenn Russo, in contrast, had a completely different attitude and personality. Nothing bothered him. He was loud and very aggressive. He enjoyed having the power of being a police officer.

Russo never talked about why he was transferred from the Narcotics division to Western. Somehow, he went too far in his enforcement of the law. Ironically, I would also face the same consequences in my undercover drug investigations in a couple years. There is always a limit as to what you can justify, cover up and get away with.

Years later, when I was undercover in Narcotics and organized crime, I would learn that Sergeant Florey was committed to a mental hospital. Because of his sensitivity and concern for his men, Florey’s mind snapped after one of his squad was killed in a shooting. Sergeant Tim Florey, one of the most compassionate police officers I knew, had a psychological breakdown, stole a car, drove it to Ocean City and torched it. Sometimes you just do not know how to vent your anger or express your emotions as a cop. I was reminded of Florey’s way of coping with life when I was confronted with PJ’s death.

Unlike the security, warmth and semi-comfort of a patrol car, a foot post officer cannot just park his body on the street, or hide in an alley, and write incident reports. We always had reports to write before the end of shift. Actually, this limitation was really beneficial in respect to maintaining police-community relations.

I established three street offices – Leon’s Pig Pen, Sugar Hill and Little Willies. All three locales were hot spots for neighborhood socializing. In a strange way, I always felt safe. I felt at home. When you walk the streets, you learn from the streets. You have to create relationships and contacts or you will not survive. You need to use more than your own two eyes and ears to see and listen.

In the beginning, I chose Leon’s Pig Pen, Sugar Hill and Little Willies because of their suspected activities as well as to annoy and irritate the owners and patrons with my police presence.

Initially I would just walk into each location, introduce myself and ask to use a table or sit at the bar and write my reports. Reluctantly, the owners always allowed me. The tone and the loudness of the conversations always changed. How could they not feel uneasy? I was a white, uniformed police officer in an all black establishment. That was just not normal.

At first, the customers were very uncomfortable with my presence but eventually most people accepted me and I created a lot of good relationships. As a bonus to the owners, there were fewer fights and disturbances. I just walked in, sat at the bar, got a cup of coffee, said hello to everyone and wrote my reports. Every shift, I would choose a different location. I called it grassroots police-community relations.

Although each one of us, as probationary police officers with less than a year on the force, had our own personalities and home environments, when we came together on shift we were one unit. We had our differences of opinion as to how to enforce the law, but we were united by one common denominator. We were all police officers and proud of our profession. We even had a unique sense of pride in our assignment to Western. It was like a status symbol to us. And we knew that we could depend on each other, no matter what the situation.

Some of the guys had nicknames like “Igor” and “Swamp Gas” (use your imagination) but that was just comic relief during roll call as we prepared to walk the streets. We knew that each shift would bring new drama.

As the weather became warmer, our foot patrol squad became more aggressive. We decided to hold a contest to see who could make the most traffic stops and write more moving violations on foot within a month. It was an interesting game and a very competitive sport because of the degree of difficulty involved. Making a traffic stop on foot could be a challenge. We were determined to write more traffic tickets and have a greater number of motor vehicle arrests than the sector patrol cars.

Although it was a squad competition, traffic stops on foot was an individual sport. There was always a certain amount of risk involved in stepping out in front of traffic on a busy street and pulling over moving vehicles at random at night. You never knew what to expect. But that feeling of uncertainty only added to the thrill of the game.

In just a couple weeks, individually our small foot patrol squad pulled over more vehicles than the patrol cars. We checked drivers for valid licenses, registrations and insurance. And we increased district statistics.

It was a game of chance but we also produced results. Every ticket written was counted as an arrest. We had more DWI’s, drivers with outstanding warrants, unregistered vehicles and drivers with suspended or revoked licenses than any other unit in Western.

Some people felt like they were being harassed. And in a way they were. But we made our quota. The game was all that mattered and it passed the time between calls. Besides, harassment was such a relative term for the game. We were only enforcing the law, right? Was it legal? Was it ethical? Did the game produce end results?

The technique of ‘airmailing’ parking tickets was another fun game to play. If a driver would not stop or pull over, we would write down the license plate of the vehicle. We would call in for registration check and ownership information. Then we would write a parking ticket. We would then tear up the copy that goes to the registered owner of the vehicle, throw it into the air, and airmail it.

The driver, or the owner of the vehicle, would not be aware of the ticket and later fined. A warrant would be issued and need to be paid before license renewal. It was a simple and fun way to repay the people who did not respect police or the law. And we were the law in Western District.

By the end of March, the weather was changing from the dark and cold days of winter into the freshness of spring. It felt good to walk the streets of Pennsylvania and West North Avenues. I still carried my custom made nightstick and strapped the snub nose revolver and knife on my legs.

I continued to write my incident reports on the streets but now I found a fourth oasis, The Arch Social Club at the corner of Pennsylvania and West North Avenues. This was my daytime office. Leon’s Pig Pen, Sugar Hill and Little Willies were still my night locations.

Our squad began a new phase of training – after-shift drug raids. This was an all-volunteer operation because there was no authorized overtime. If you wanted to go on a drug raid, you did it for the thrill, for the experience and for no other compensation.

Glenn Russo had been apparently renewing his connections with informants on the streets. And now, as our training officer, he had his own mini drug taskforce.

I knew where I wanted to be in a couple years and this new dimension only reinforced my goal to be assigned to the Narcotics division. For me, these raids became the beginning of an addiction I had for the rest of my time as a police officer. I became addicted to narcotics work.

There is no way to express the euphoric feeling you have when you are rushing to knock down a door and run into a house without knowing what, or who, is really on the other side. The adrenaline rush is like a drug in itself. For me, the climax was never the arrest. It was that sense of knowing that you are about to win the game.

Once you get that injection of power in your veins, you are hooked, but only if you are good at it. In a sense, you develop a pathological disorder. There is no other assignment like Narcotics on the police force. In Narcotics work you actually have the ability to create the crime.