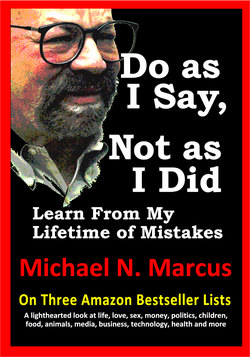

Читать книгу Do As I Say, Not As I Did - Michael N Marcus - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеMy Worst Mistakes

My worst mistakes (so far) involve money. Judging by the huge number of people and books providing financial advice, maybe most of other people’s worst mistakes involve money.

I became 68 years old in the spring of 2014. My wife and I collect several thousand dollars each month from Social Security. When we were younger we assumed that Social Security payments would buy us a second home and nice vacations. SURPRISE! We need the money for basic living expenses. I hear the same thing from many others.

Lesson: It’s tough to predict the future.

We have a big, beautiful house that’s theoretically worth a lot of money. We have lots of equity in the house, but we can’t eat the equity.

Lesson: If you need to buy food it’s much easier to liquidate an IRA than to sell a piece of a house.

My income went up from the early 1970s until around 2007. My wife and I didn’t live like Donald and Mrs. Trump but we could afford to pay nearly $100,000 for a swimming pool and more than $3,000 for a piece of French-made furniture. Today I’d much rather have the $3,000.

Lesson: Before you buy a non-necessity for $3,000 or even $3, think about whether at some time in the future you’d rather have the money.

My wife and I didn’t think we were rich, but we were “comfortable.”

Including non-liquid assets, we were multimillionaires for several years. We could easily afford anything that was important—and many things that were not important.

We bought flat-screen TVs and Blu-ray players before the prices came down. Our dog drinks Poland Spring water. (I am satisfied with filtered water from the fridge.)

On the other hand, we never gambled more than $25 at casinos, didn’t smoke or use recreational drugs or gamble on Wall Street—and spent almost nothing on alcohol, jewelry or vacations. We’ve owned three boats, but they were all inflatables that cost about $15 each.

We put a lot of money into IRAs.

We always tried to buy things on sale and make expensive purchases with a year to pay and no interest. We used credit card points and “miles” to pay for flights, hotel rooms and gifts. We had two timeshares on Cape Cod—bought cheaply from the estates of the previous owners.

We gave to a score of charities each year and helped some less-fortunate relatives.

We had dozens of credit cards with huge credit lines and perfect credit ratings.

In 2005 I turned down an offer of about $4 million for AbleComm, my telecommunications equipment business.

•I was not ready to spend the rest of my life on the beach.

•I liked what I was doing but didn’t want to do the same work for a boss instead of for myself.

•I didn’t know that the Great Recession was on the way.

Before the recession, the telecomm business was so good that my small company had over $100,000 in the bank, paid its bills early to earn discounts and even invested surplus funds overnight.

Then, in 2007, the shit hit the fan. It was called the “Great Recession” but “great” did not mean better than “good.”

Because of general economic malaise, more competition and lower sales prices caused by innovations in technology, my telecommunications business’s sales gradually decreased.

Now, in 2015, it’s increasing, but very slowly, and it’s unlikely to ever reach its previous high. Silver Sands Books, my tiny publishing business, provides me with hundreds of dollars each month—not thousands. I thank you for buying this book.

When the recession officially ended, we got a home equity loan to pay off high-interest credit card bills. We—and many experts—thought that happy days would soon be here again.

We optimistically, naïvely and foolishly agreed to a five-year loan with monthly payments of nearly $5,000 (on top of our first mortgage payments of about $1,800 per month).

In the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy in the fall of 2012, my business had no phone service, email or electrical power for a week. We did no business. I had no income. I asked our “friendly banker” to give us an additional ten days to make the scheduled huge mortgage payment.

Instead of authorization, I was given a bulging packet of forms to fill out for the “loss mitigation department.” There was no loss that needed mitigating. I just needed a relatively small favor from the “helpful, understanding, compassionate and community-minded” bank.

It would seem that the manager of my local branch, which had provided services to me for over a decade with no troubles, could easily authorize a ten-day extension. But, no. I’d have to fill out all the forms and send them to another state.

But wait—I left out the best part.

The bank manager told me it could take 60 to 90 days to find out if I’d be granted the ten-day extension.

I never filled out the forms and simply made the payment eight days late and paid an annoying penalty fee. Today, banks depend on fees for a substantial part of their income and are extremely reluctant to cancel a fee.

According to the Wall Street Journal, “years of low rates on mortgages and other loans have eaten into the income banks collect from interest charges, an important driver of bank earnings. ‘Banks have a revenue gap that needs to be recouped,’ said Greg McBride, chief financial analyst at Bankrate.com, which tracks overdraft fees and other charges.” Fuck ‘em.

Oh yeah, our health is deteriorating, too—just as the cost of medical care is increasing.

If I was sadistic I’d smile at the revelation that even doctors are having financial trouble. According to CNN, “Doctors in America are harboring an embarrassing secret: Many of them are going broke.”

Here in Connecticut, traditionally a very wealthy state, we’ve seen many businesses close (including some of my favorite restaurants, and two restaurants opened and closed before I had a chance to try them). Some neighbors’ houses have been foreclosed. I know people who say they will work until they die.

One couple we know used to spend a lot of money on designer clothes and other artifacts of affluence. The husband was a highly paid Wall Street executive and the wife was a busy stay-at-home mom with four high-maintenance kids. They had a big house in the country which they started enlarging—but one door goes nowhere.

The family’s finances deteriorated to the point where she delivered newspapers early in the morning and he worked part-time as a Kmart security guard.

Their house was foreclosed, they went bankrupt, sold most of their personal possessions and fled to Southeast Asia where they can afford to live on what Social Security pays them. They seldom get to see their children in the USA.

I used to think that their situation was both pathetic and avoidable. I’m not critical anymore and I wonder if they can find us a cabin and good doctors in Cambodia.

•In retrospect I probably should not have used personal money and credit lines to finance my telecommunications business—but most owners of small businesses do just that.

•In retrospect I probably should not have paid about $2,000 for merchandise displays that were hardly ever seen because most of our customers bought online.

•In retrospect I probably should not have paid about $5,000 for signs because most of our customers bought online.

•In retrospect, I probably should not have spent $1,500 on artwork and $2,000 on carpeting to make the office a nicer place to work than it would have been with bare walls and concrete floors—but we could afford it at the time.

•In retrospect I probably should have used ceiling fans in the warehouse and office instead of spending $8,000 on air conditioning (which the landlord inherited when we moved out)—but we could afford it at the time.

•In retrospect I probably should have spent $80, not $800, on an office refrigerator—but we could afford it at the time.

•In retrospect I probably should have spent $500, not $2,000 for a backup battery system for our phones and computer network—but we could afford it at the time.

•In retrospect I probably should not have paid $4,000 to business consultants—but we could afford them at the time.

•In retrospect I should not have paid $8,000 per month on Google advertising—but we could afford it at the time.

•In retrospect I probably should have fired an employee the first time I caught him stealing instead of giving him a second chance. (He stole again.)

•In retrospect I should have replaced an accountant the first time he made a mistake that cost me thousands of dollars in IRS penalties.

•In retrospect I probably should not have sent out beautiful color postcards to government purchasing agents—but it seemed like a good idea at the time.

•In retrospect I probably should not have sent out beautiful color postcards to pizzerias—but selling “pizzaphones” seemed like a good idea at the time.

•In retrospect I probably should not have let a bookkeeper decide that it was OK to pay bonuses to employees.

•In retrospect I should not have bought 1,000 souvenir pocket knives to commemorate our 30th anniversary—but it seemed like a good idea at the time.

•In retrospect I should not have set up a wholesale division—but it seemed like a good idea at the time.

•In retrospect I should have checked the computer skills of a guy who bragged about his skills—but could not use simple software.

•In retrospect I should not have hired a salesman who was terrified to speak on the phone.

•In retrospect I should not have waited so long to fire the employee who called in sick on at least one Friday or Monday each month.

•In retrospect I should have fired a nasty, disrespectful employee who made me hate going to work in my own company.

•In retrospect I should have gone to work earlier in the morning so I could have caught an employee who was running his own business with my inventory.

•In retrospect I should have spent less money on my commuter car.

•In retrospect I should not have tried to manage 40 websites for various facets of my business.

•In retrospect, I probably should have stopped renting a warehouse and office, fired some employees and squeezed the business into my house sooner than I did—but I kept hearing that the economy was improving. I believed the experts.

Some people say I should have just shut down the business—but it’s hard to abandon a business that provided a nice life for over 30 years, and still had inventory, customers, employees, websites and a good reputation.

It’s very difficult to say “I messed up” and just walk away.

Lesson: If someone offers you millions of dollars for your business, take the money and run.

From the U.S. Dep’t of Justice