Читать книгу The Lynchings in Duluth - MIchael Fedo - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Foreword

ОглавлениеWILLIAM D. GREEN

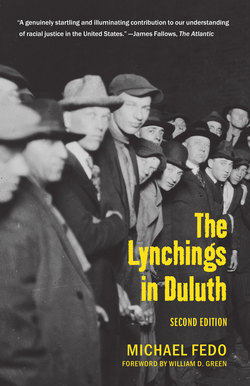

In Duluth, Minnesota, during the summer of 1920, between five to ten thousand people clogged the street in front of the police station to witness the hangings of three black men. Reporters of the two major newspapers of Minneapolis and St. Paul shocked their readers with lurid accounts of the event. In fact, leading newspapers throughout the North vilified Duluthians for having stained their city’s good name and castigated them for being no better than southern racists. Gov. Burnquist, then president of the St. Paul chapter of the NAACP, had commissioned his adjutant general to launch a formal investigation. Three dozen men were indicted for being in the mob. And one year later, in reaction to the event, the state legislature enacted an antilynching law. Yet, by 1992, it was as if the event had never occurred. I had never heard of the incident. No one I knew had heard of it. For most Minnesotans, the intervening years since the lynchings would obliterate their collective memory, leaving a diminishing handful to treat it, like all dirty little secrets, as something best left unspoken. It was then when I heard that a book by writer Michael Fedo recounted the event, but that the book was hard to find. None of my usual sources could help me locate a copy since it had been long out of print. However, through the tenacity of a bookseller friend whose avocation was tracking down out-of-stock books, I eventually was able to obtain a copy.

What I read was an astonishing chronicle of an event that defied everything I thought I knew, not only about lynch mob mentality, but about my adopted state of Minnesota. Indeed, the scope of the incident was as tragic as it was unbelievable. During that period the lynching of black men was typically a rural, southern phenomenon and conducted with impunity, and the Duluth incident was none of these (although only three of the lynchers were convicted and only for the crime of rioting). I was impressed with the sober treatment in which Fedo wrote the account, letting the facts speak for themselves devoid of self-righteous melodrama. I was impressed with the care he took in recounting the small but telling stories of individual participants and observers in a manner that cast them as ordinary people caught up in an extraordinary moment. Unfortunately, the work did not include footnotes, and this concerned me; but as a result of my own study into the legal and social consequences of the lynchings on the city, I have found myself able to vouch for the accuracy of Fedo’s research. It is an account on which the reader can rely and a story that needs to be told.

My own department of history at Augsburg College agreed with me when I wanted to hold a Day In May program with the Duluth lynchings as the theme. Not since the early seventies had the college used the first day of May as a time dedicated to serious discussion and reflection. Instead, over the years the Day’s observance evolved into a time for fun-filled celebration that heralded the arrival of spring and the end of classes, complete with balloons, loud music, and the fatted calf of college cuisine—cheap hot dogs and pizza. It hardly seemed a time for examining such a somber topic. Nonetheless, we put together a panel of speakers, which included Fedo, posted notices around campus, and secured a moderate-size room for the occasion. Because the day of the event was warm and sunny, and the discussion was to convene in the afternoon, no one expected many to attend. Already you could hear the persistence of bass guitars and drums booming from speakers in Murphy Park across the street when I entered the room, but what I found inside was stunning: it was standing-room only. Students, faculty and staff, and a sizable number of retirees filled the room. Though we hadn’t determined how long the discussion should last, I think we all anticipated that after an hour people would begin to leave. However, the discussion, in which the audience later participated, lasted for an astonishing three and a half hours. The topic proved to be not only one that was important to share but one about which people wanted to learn.

I think the importance of the book also is in its potential for serving as a device through which we can examine the terrible quandary of moral dilemma. Under horrific circumstances, would one exert strength in following a moral directive or choose to go with the crowd? As Fedo asked me over lunch recently, if one of us was the young man who had climbed the streetlamp in order to get a better view, how would we have responded when the large crowd of men, some of whom we knew, beckoned us to secure a rope that would be used to hang a man we didn’t know? At what point is one’s guilt by association manifest? When he fastened the rope? When he climbed the streetlamp? When he went downtown? In the false security of hindsight is it fair to judge him? Indeed, is it fair to ourselves to be judgmental? In asking such questions, will we learn enough about the forces that incite the bestial quality within our collective soul? Given the presence of dislocating forces on society that emanate from social, political, and economic forces, can we distinguish individual responsibility from the community’s? Is vigilance against mob action the central lesson that we must learn? And if so, can our society ultimately advance if vigilance keeps us from talking about race? The importance of Fedo’s work comes from the opportunity it provides by challenging us to navigate, as Homer’s Ulysses did, through straits made tempestuous by the twin demons Scylla and Charybdis.

During one of my weekly walks with a colleague from Augsburg, I began telling him of a tragic racial encounter in history that I was then researching. Although I was using him—a strong analytical thinker as well as a very good writer (notwithstanding his training as an accountant)—as a sounding board for some of the prickly issues I wanted to explore in an article I was struggling with, I was unmindful of how he was reacting to my anecdotes. Indeed, I was surprised when he told me how disturbed he felt at what I was saying; that otherwise reasonable people were capable of performing the most bestial acts imaginable, being motivated to do so not so much in the name of white supremacy but too often by far more banal instincts; that it happened so often, in so many different settings, at any prompting; and that such acts occurred with impunity. How could I live with such knowledge, he wondered. Didn’t it leave me haunted? Didn’t it fill me with rage? How on earth could I endure functioning as a scholar and teacher without giving in to the dark temptation of becoming an ideologue?

I was struck by both his questions and his passion, for he was reacting to the cumulative effect of incidences that I had shared with him over the years, while I in turn appeared clinical. I wondered what had happened to me. Had I indeed grown emotionally callous as I sought to unearth such incidences? In wanting to know about them was I spurred on by prurient design to debunk the reputed legacy of Minnesota Nice or seek retribution on white contemporaries for the sins of their fathers? I do not think so. This is not about exploiting white guilt. Tragedy is very much a part of the human drama, and as students of history we must know that it exists in order to fully know who, and what, we truly are. And yet, I was bemused by my friend’s assertion that I seemed so disassociated from the tragic episode. That I could speak dispassionately of such events did not mean that I was untouched by these occurrences. Quite the contrary. At times I wished that I never knew of such things, living instead in blissful ignorance; but it is a fool’s paradise.

For much of my life, I knew what was possible, that an otherwise banal event such as white drunks boasting idly, could suddenly get out of hand and turn ugly. Consequently, it governed my behavior, sharpened my instincts, enhanced my resolve to be discreet, vigilant. This was my upbringing. Survival often meant simply getting through the day. This, for sure, and thankfully, is a foreign concept to most people today. But for those of us raised in the Deep South during the fifties and sixties—whose racial forebears, too numerous to count, were victims of the rope—the wounds have healed but the scars remain. We can never forget. We must never forget. The test, of course, is what we do with the memory. Do we allow it to fester? Or do we use it to illuminate? Does knowledge of the event perpetuate our victimization? Or do we use it to set us all free?

In my youth we used to embark annually on monthlong family vacations that took us to various sections of the country, New England, the Southwest, etc. The car was our means of transportation; and even though for us it was the only cost-effective way to travel, my parents insisted that this was the best way “to really see America and get the feel for people,” as my father used to say. Getting the feel was indeed educational, for, coming from New Orleans, we would have to traverse over miles of southern roads, through innumerable southern towns and hamlets before crossing the Mason-Dixon. The plan was always the same: pack a lot of food, coffee, and juice; be on the road before sunrise and get as close as possible to the fabled Line before we needed to stop for a nature call. After all, this, during the late fifties and sixties, was still the unreconstructed South. Though my youthfulness cast the trip as an adventure, and my mother tried reinforcing that sense by reading to me, my father sat rigidly forward, both sweaty hands gripping the steering wheel, staring at the road. Neither parent chanced looking out over the southern countryside, as if to avoid at all cost making eye contact with passersby noting a carload of coloreds who had not stayed in their place. It was only after having left the South that you could feel the lifting of the quiet tension they felt. At last, they could both relax. Only then would my father insist that I take in the countryside. Here, my stately father—all six foot, three inches of him—was no longer Boy.

As a child of the city I never actually saw the bestial deeds of mob rule. That typically was a rural phenomenon. Nonetheless, as a child of the times, I learned that being an African American male alone made me perfect fodder for racial hatred that could show itself at any time. I knew about Emmett Till. Even more chilling was the fact that such acts could be random. Racism was as pervasive as the air we breathed. Not until all of America became glued to the Evening News that depicted civil rights demonstrators who faced the fire hoses, police dogs, and nightsticks that enforced the power of southern segregation did most people have a clue of what we experienced daily. It was always safer just to stay in our place when vacation time rolled around: never leave our neighborhood, never be exposed to the larger world, never know of the range of choices that black people lawfully had. I believe that our family vacations on the road were not just excursions to interesting spots in the country; they were for my parents, I now believe, no less than acts of defiance.

I had a sense of this during a return trip from Niagara Falls. The year was 1964. Congress had just passed the Civil Rights Act which forbade discrimination in, among other areas, public accommodations. Despite strong showings in northern primaries for George Wallace, Lyndon Johnson was favored to be reelected president. Nonetheless, it was also the year of the so-called long hot summer. Northern ghettos were exploding in civil strife. Southern cities staged Klan parades that protested racial equality. That August the liberal Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, whose delegates seeking to be seated at the national convention would be frustrated by party officials in favor of the regular segregationist delegation, held its first statewide convention. Days later, the martyred bodies of three voting rights activists—James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner—would be unearthed. But at age thirteen, as we drove home through Mississippi, I was only interested in seeing my friends

I remember that my father had mentioned that we were running low on gasoline and that he wanted to try to make it to Jackson, but we couldn’t. We had to stop in a service station in some small town whose Choctaw name was longer than Main Street itself. While gas was being pumped, my mother decided to go to the restroom. The gas station, as was typical in the South, had three restrooms. In the shadow of federal law, establishments like this gas station could no longer discriminate on the basis of race; and so, where signs depicting “Men,” “Women,” and “Colored” once hung were now simply “1,” “2,” and “3.” In this town, like most southern towns, federal law was at best a minor inconvenience. Each door now required a key to be dispensed by the attendant, and in this town he was a native son. When my mother entered the station office, the attendant was not present, so she took the key designated for “2.” By the time she returned with it, the attendant was standing at the desk talking with two other white men. All three took note of my mother’s breach of social custom, and they followed her outside and stood at the rear of our car, where they seemed to be studying our Louisiana license plate. Having paid for the gasoline, my father now sat anxiously behind the wheel, his neck turning red. As we drove down the lonely roads of southern Mississippi, I remembered how he constantly checked in the rearview mirror to see if we were being followed. It was at that point that I realized the full impact of abject terror though I didn’t then fully comprehend what was happening.

I never forgot that trip home and the fear I felt emanating from my father, but it wouldn’t be until adulthood that I would begin to understand. Along the roads we passed and off in the distance were groves of pine trees. How many bodies were buried out there? Black people who didn’t know their place. Innocents, perhaps, deemed nonetheless to be impertinent. It would be years before I realized the unique kind of terror that blacks felt, for it was the sort that came not only from realizing your own vulnerability to random or concerted acts of harassment, torture, and murder, but from being a victim with no one around to bear witness. Without such witness, an extinguished life is one without closure. It is in this spirit that these introductory remarks bear witness. It is only proper that such witness invites the reader into The Lynchings in Duluth, for within the following pages is Fedo’s own gift of closure for Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson, and Isaac McGhie, who died in Duluth on June 15, 1920.