Читать книгу The Lynchings in Duluth - MIchael Fedo - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Preface to the Second Edition

ОглавлениеThrough the decades since this book’s initial publication, I have discovered, to my surprise, that in many ways my life has been informed by the long-ago murder of three innocent black men on a downtown street in the city where I was born and raised. It begins with a question posed by the Zen philosopher: If a tree falls in the forest and no one is present, does the falling tree make a sound? For students of history, the question might be, if an event occurred and no one remembers it, did it happen?

By 1973 the story of the Duluth lynchings had been long absent from public discourse and classroom reference. The city—indeed, the state of Minnesota—had “forgotten” the historic event. Textbooks on Minnesota history, and even a detailed history of crime in the state, pointedly omitted the hangings in Duluth.

Serendipity would return the incident to public awareness, and I am grateful to have a part in this overdue conversation and remembrance. That year I determined to write my first novel, and for reasons long forgotten, I chose to place the story in post–World War I northern Minnesota. Prior to beginning the writing, however, I recalled something my mother had mentioned years earlier when I was a lad of nine or ten. She said that when she was a little girl, three black men had been hanged on a downtown street corner, slightly more than a mile from where we lived. I could not then, and still cannot place her reference in any context. Indeed, I still wonder what possessed her to relate this incident to me. I do not recall being struck by the story when I first heard it, but it lodged in the recesses of my mind for decades, suddenly surfacing as I contemplated my novel.

I considered including the lynching scene as a chapter in the new book, with a main character witnessing the killings. I sought to locate the book I assumed had chronicled the event fifty years earlier, read it for accuracy, and incorporate details into my own text. But no such book existed, and none of the half dozen Minnesota libraries I consulted had records of that fateful June night in 1920. No one, it seemed, had even heard of the murders. However, a librarian at the Minnesota Historical Society in St. Paul informed me that he had discovered a file on the lynchings and I was welcome to peruse it.

The manila folder contained several newspaper clippings and a pamphlet detailing what happened in Duluth during the evening of June 15, 1920. Following review of this material, I uncovered other information from the History Center’s archives, and after three Saturdays poring over old newspapers and records from the governor’s files, supreme court transcripts, and notes from other state officials, I had filled a spiral notebook. At this point, I abandoned the novel and set about documenting what happened in my hometown on a night that forever impacted racial attitudes of citizens in northern Minnesota, and perhaps throughout the Upper Midwest.

Moving forward with this project, the questions that impelled the research and writing were: How could such a thing happen in Duluth, Minnesota, a far-northern city of a hundred thousand citizens, with fewer than five hundred of them African American? And why did almost no one remember or even know about it?

There seemed a concerted effort on the part of many city officials to forget the tragedy happened, to expunge it from conversations and records. For more than half a century, lynching deniers held sway in northern Minnesota. Indeed, an employee at the St. Louis County Historical Society told me that the society had maintained a file on the lynchings for a number of years, but the director ordered it removed. Also the clerk of court in St. Louis County back in 1973 stated that all court records from trials following the lynchings had been ordered destroyed by a local judge. A neophyte investigative reporter, I believed him, and indicated this in the book’s initial incarnation. Several years later, following regime change at the clerk of court office, I received a letter from a Duluth high school student who said, “In your book, you claimed court records were destroyed. Well, I got them two weeks ago for a report in my history class.”

Even persons who agreed to talk to me wondered why I wanted to dredge up so unseemly a subject that would not reflect well on my hometown. Some book reviewers thought the same thing, as shown in this assessment from the September 23, 1979, Minneapolis Tribune: “Now, nearly 60 years later, Michael W. Fedo, a Duluth native … has chosen to rub our noses once again in the awful events.”

That most reviewers were more charitable and far less chauvinistic than the Tribune critic did not generate sales. “They Was Just Niggers” was an appropriate but inapt title. With a minimal advertising budget from the fledgling West Coast publisher, the book was relegated to back-of-the-store shelves under Regional or Sociology labels. Customers seeking the book were too embarrassed to ask for a book with the N-word. The initial edition quietly disappeared from stores within several months of its release.

The book soon disappeared even from remainder bins, and the story I assumed might generate interest in an important but forgotten incident seemed dead. But in 1993 Harlin Quist called and offered to republish the book. Quist, a former off-Broadway actor and producer, had earned a solid reputation as a Paris-based publisher of lavishly illustrated children’s books. Among the luminaries he published were Eugène Ionesco, Robert Graves, Edward Gorey, Mark Van Doren, and many, mostly French, illustrators who subsequently attained international eminence.

Quist was on hiatus from his Paris operation, returning to his hometown to care for his ailing elderly mother. He was bored and searching for new adventures. He was going to refashion the downtown Norshor movie theater into an arts center where local artists, writers, and musicians would have a quality venue for exhibiting and performing. He thought profits from my book would help jump-start the operation.

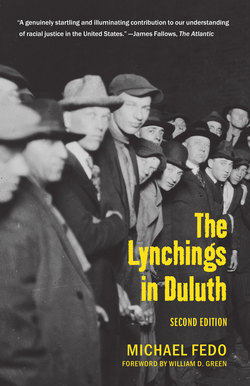

His newly designed book was retitled Trial By Mob, but it too quickly disappeared, as Quist, encountering financial glitches, left town—bills unpaid, no forwarding address. Fast-forward to November 1999. Sally Rubenstein, an editor with the Minnesota Historical Society Press, phoned. The press would like to reissue the book with a new title: “The Lynchings in Duluth.”

I signed a third contract for the book, and it was released in June 2000. This time, the reception was more favorable. The book received attention from the PBS News Hour and National Public Radio’s All Things Considered and was mentioned in the London Times and in Paris’s Le Monde and in an Atlantic blog by James Fallows. High school and college classes throughout the Midwest and beyond were reading and discussing the book, and I was often invited to participate in those discussions. Barry Schreiber, professor of criminal justice at St. Cloud State University, had adopted the book for his introductory class well before the 2000 edition was available (cobbling used copies for students), and in addition to having me talk to his classes, had lobbied for the book’s reissue. Further, Duluth citizens came together to form the Clayton Jackson McGhie Memorial Committee not only to oversee appropriate memorials for the victims, including art and poetry, scholarship funds, and an annual march to honor them, but also to join ethnic and religious groups together in unity against the evils of racism.

For this new edition of The Lynchings in Duluth, some minor alterations have been incorporated into the text. These changes, suggested by historians, were items that I, as a neophyte author back in 1970, missed while preparing the original manuscript. In a few instances, I may have relied too heavily on accounts given by persons interviewed, whose own recollections were fuzzy or took on greater import in their minds during the five decades between the lynchings and the time of those interviews. And, citing the absence of footnoted documentation, some academicians have been reluctant to use the book as a classroom supplement. However, more than forty years ago, my intention was to create an account that would have broad appeal to general readers.

The most notable change in this second edition is the inclusion of the real names of Irene Tusken—the alleged victim of the sexual assault that led to mob action and the hanging of three young men—and James “Jimmy” Sullivan, her escort to the circus on the night of June 14, 1920. In the original text I employed aliases for the two because I was told by two important interview subjects that they wouldn’t speak to me unless I altered the names of Tusken and Sullivan, with whom they were acquainted. Because their participation seemed necessary to complete the book, as a young journalist I acquiesced, much to my later regret, especially since, following the book’s initial publication in 1979, those names were widely published elsewhere. Unfortunately, I did not attempt to convince those interviewees that it might be disingenuous to alter those names.

This second edition still does not include the apparatus of an academic document, such as footnotes or end-notes, primarily because research materials recorded from 1970 to 1973 were lost or discarded following the original publication.

One reviewer suggested that I remove from the text quotes, dialogues, and references that cannot be documented. However, all of these came from sources with tangible connections to the story: relatives and acquaintances of eyewitnesses to the tragedy. Also, I was attempting to write a book that is more accessible to a general reader and wanted to sustain the hour-by-hour narrative incorporating a more immediate, more dramatic approach than the use of the indirect quote. If this be not scholarly, it is, I think, more readerly.

I have also made important corrections to the main body of the text, thanks to the attention and care of reviewers and scholars of this historical period. I subsequently learned that there was no activity by members of the Ku Klux Klan in Duluth preceding the lynchings, and I have corrected that in this edition. I relied on several interviewees who mentioned cross burnings in the city. While these did occur, none were prior to the lynchings. One reviewer pointed out that the connection between workers at the U.S. Steel mill in the Morgan Park neighborhood and racial tensions because black workers were brought in to keep white laborers from striking for higher wages in the aftermath of World War I was only speculative, as no strike occurred. True enough; however, three longtime black residents of Duluth (all since deceased) made pointed comments regarding the importation of a few southern cotton field workers, which, they said, helped convince current employees to not strike. I did not report that a strike occurred at the Morgan Park plant.

If Duluth was once a city with collective amnesia, it is now very much a city with citizens willing to confront its past, admit its sins, and move forward in a spirit of forgiveness and togetherness. And in the process they hope to heal the city’s open, unspoken wounds that had festered for decades.

MICHAEL FEDO

DECEMBER 2015