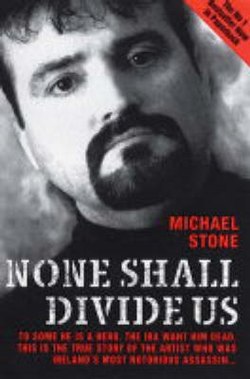

Читать книгу None Shall Divide Us - Michael Stone - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

TOMMY HERRON

ОглавлениеWHEN I WASN’T IN THE QUARRY BEING TRAINED I SPENT MOST OF MY TIME AT TOMMY HERRON’S HOME, SITTING ON THE STAIRS LISTENING, LEARNING AND TALKING TO HIM. He liked the stairs. He called them his neutral space and he always kept his legally held weapon within reach. Herron confessed that he was on constant alert for a gunman who might break in his front door and open fire. He would laugh and say he would do his best to blow their brains out first. Many of my new associates thought he was bad-tempered, stern, unapproachable and unpredictable. To me he was a father figure. He took a personal interest in my fledgling UDA career and I wanted to impress him. He singled me out for special attention and I wanted to repay the compliment. Under his guardianship, I thrived.

With Herron’s guidance my training became more intense and more specialised. He taught me martial arts and unarmed combat. He taught me how to punch someone in the heart to stop it beating and cause rapid death. In his mind the business of killing had to be swift and it had to be clean. I asked Herron where he learnt his skills and he just laughed in my face and told me to mind my own fucking business. To this day I believe he was a trained assassin and can only speculate as to where he learnt the skills he handed down to me.

It may seem unbelievable to some but Herron had a soft side and he liked to look after those he cared about and who were close to him. One day, as we practised shooting in the quarry, he said to me, ‘If you are ever in trouble and you need to leave Northern Ireland, call this number.’ On the paper was a name and a London telephone number. When I rang it a female voice answered. I asked for the person and was told he wasn’t available but to ring back on a certain day and at a certain time. When I finally spoke to the man, I told him I was a friend of Tommy Herron’s and that he’d given me the name and number plus a guarantee of help if ever it was needed. The voice on the other end of the phone said he could find me work anywhere in the world. He said he supplied top-grade ‘security’ for select clients all over the world. He asked whether I wanted to be on his books and I said yes. The man was hiring mercenaries.

I was enjoying my new life in the ranks of the UDA. I felt I had found what was missing in my life. In the first weeks after joining very little was asked of me by my superiors. I knew that time would change that. I knew it was inevitable that I would soon be on the road on active service. In the meantime I shadowed Tommy Herron. While I acted as his bodyguard, I was also learning. He had four men acting as his personal security, including me, and he rotated us at random.

I chanced upon a photograph of Herron recently and it awakened old memories. He’s been dead almost thirty years now but I can still hear his gruff voice. It was an old newspaper cutting illustrated by a very bad picture. In it he is frowning and looks like he is ready to blow someone’s head off. The photo revealed nothing about his personality and character. Herron was a hothead. He was rash and quick-tempered and probably would have blown someone’s head off, but he was also an intelligent and astute soldier. Neither the article nor the photograph showed anything of the Herron I knew and portrayed nothing of the man I remember, a man with a sharp brain, impressive intellect and remarkable powers of persuasion. Listening to Tommy speak, I really believed anything and everything was possible. Even the media were seduced by his charisma. Journalists flocked to his press briefings. He knew how to handle them and when he held court, anything was possible. Once he produced rubber bullets that he said had been doctored by the British Army. There had been rioting in East Belfast and four bullets were found with razor blades, four-inch nails and batteries attached to them. One was even split and rebuilt using fine wire. On impact it would have turned into a deadly bolas.

We spent a lot of time together in Davison’s Quarry and he liked to show off his shooting skills. He loved emptying magazine after magazine into oil drums and the bodies of scrapped cars. He had a good eye and could even shoot in circles or in rows. He would roll up his sleeves, coolly take aim and say to me, ‘Watch this.’ He was a first-class shot.

The Ulster Defence Association remains one of Ulster’s biggest paramilitary organisations and was legal until 1992, when the then Secretary of State, Sir Patrick Mayhew, proscribed it. It was formed in 1971, when Ulster was on the brink of all-out civil war, as an umbrella body for Loyalist ‘defence associations’ springing up in Protestant areas of Belfast, Lisburn, Newtownabbey and Dundonald. It adopted a motto, Quis Separabit, roughly translated as ‘None Shall Divide Us’, and the UDA quickly became a formidable force in Loyalist districts. Many young Loyalists saw the UDA as a replacement for the B Specials, a part-time paramilitary force that was abolished in 1969, and offered their support by the truckload. The UDA was distinctly working class and organised along military lines. When I joined, in 1972, it had a membership of forty thousand.

The UDA has had a varied history and its thirty-year existence is littered with violence, strong-arm tactics in support of Loyalist protests and journeys into political thinking. Tommy Herron was an architect of all of these things, especially the Loyalist street protests. He told me he got a kick out of watching thousands of men assembling in combat gear and making themselves ready for action. In 1972 thousands of UDA men, many wearing masks, marched through Belfast city centre. I was one of them. Herron was one of the chief organisers. As I walked with my fellow Loyalists I felt I was living up to the solemn promise I’d recently made. I was making a difference. I was making a contribution. I was a defender of my community and here was the proof: my combat uniform and mask and a triumphant march through the streets of my city.

Herron was once again at the helm in July 1972, when plans to erect barricades between the Springfield Road and Shankill Road led to eight thousand UDA men, in full uniform and carrying iron bars, confronting three hundred members of the security forces. It was an ugly situation, the Protestant community turning on its police force. Herron regarded the offensive as a spectacular example of the speed and efficiency that an ‘army’ could be assembled at short notice. It was his intention to build on this in the months to come but his murder changed everything.

He particularly hated the Welsh Guards because they called all of us ‘Paddies’. He always encouraged us to get a riot going with them. Herron had a master plan for his young recruits: you get caught, you get sent to prison and you then get to finish the rest of your training in the ‘University of Terror’ – Long Kesh.

In my new role as a UDA volunteer many things were expected of me, including the procurement of funds and weapons. That meant I stole cars and took part in robberies. Three weeks before my seventeenth birthday I appeared before a resident Magistrate at Newtownards Petty Sessions. I was found guilty of handling stolen goods from two robberies and was given a twelve-month conditional discharge and ordered to pay compensation. My new life had begun.

No sooner had I walked from Newtownards Court when my superiors ordered me to steal weapons and ammunition from a sports shop in Comber, County Down. An accomplice stole a car; we broke into the shop after dark and took three shotguns and several thousand rounds of ammunition. I only got caught because my sidekick, high on adrenalin after the robbery, couldn’t keep his mouth shut. He bragged about the robbery to his girlfriend, she told her father, who was a policeman, and he was lifted and questioned. He even squealed on me. I got lifted and was charged. He went to court and got a suspended sentence. I went to court, Saintfield Petty Sessions, in June 1972, and was charged with possession of firearms and ammunition. I pleaded guilty.

Judge Martin McBirney asked me why I stole guns and bullets and I told him I needed to sell them to make a few quid to pay a debt. I didn’t tell him I was a member of the UDA and had been ordered to steal the guns by my superiors because they were needed for war. I was sentenced to six months in prison. Judge McBirney ordered prison because I was under licence from my last court appearance. He died very shortly afterwards when a Provo unit burst into his home and shot him dead as he ate breakfast with his wife.

My first experience of jail was the Women’s Prison in Armagh. I was on remand before being moved to Long Kesh, and shared a cell with two Republicans. I was the only Loyalist prisoner there. One of my cellmates, Fish, was doing time for a sniper attack using an M1 carbine on the Army sangar at Ardoyne. The three of us even played football together in the yard. The other two knew I was a Protestant because my cell card had my name and religion written on it, but I told them I was in for theft and they left me alone. Given my age, I should have been sent to Millisle Young Offenders Centre, but the police knew I was a bad boy and had me sent to the Kesh.

There I remember entering one of the large Nissen huts, which held up to forty prisoners. It was a mixed unit and we were kept in these ‘holding’ areas while we waited to be claimed by our organisations. There were groups of mostly young lads huddled together. In those days new prisoners were not immediately claimed by their groups. Each of us had to be assessed by men on the inside who passed messages to men on the outside to make sure we were who we said we were and not Special Branch plants. A network of coded messages confirmed our identities. While we waited for confirmation, Loyalists and Republicans lived together in the same huts. It was survival, but strangely there were never any cases of one side assaulting the other.

Within four weeks of entering Long Kesh I was accepted by the UDA leadership and moved to the Loyalist compounds. I was just a young lad and here I was doing my six months alongside men doing big time for murder and attempted murder. I never met Gusty Spence, but I did hear plenty about him. I did see him once, though, striding through the prison in a three-piece suit carrying a briefcase and accompanied by two prison officials. I thought he was one of the prison directors until someone put me straight. Spence, a UVF volunteer, was overall commander of the Loyalist internees and serving twenty years for the murder of Peter Ward. He was a strict disciplinarian and ran the University of Terror along military lines. Spence was deeply resented by the UDA prisoners. We saw him as hijacking the whole Loyalist cause.

I served four months before I was released. Those four months turned me into a man – a cliché but true. I learnt things in the Kesh I couldn’t have learnt outside, and they complemented my training under Tommy Herron. The first thing I learnt was that I was militarily enthusiastic but naive. I spent my four months listening and learning from those who had practical skills I could use on my release. Through these men I learnt about active service. I learnt about explosives from bomb makers. I learnt patience by simply helping veteran Loyalist John Havern with his leatherwork. I learnt about my own history and also the history of my enemies. I now had clarity, determination and focus. I was back on the streets of East Belfast in October 1972 ready for action.

I was only out of prison three months when I was back behind bars. I needed a getaway car and was charged with ‘taking and driving away a motor vehicle’ and fined two hundred pounds. After refusing to pay the fine I was given a three-month sentence. I deliberately made the decision to go to jail rather than pay. I needed time away from the paramilitaries. I needed to step back. A teenager called Michael Wilson had been shot dead. He was Tommy Herron’s young brother-in-law and I had alarm bells ringing very loudly in my head.

Michael Wilson was ambushed as he slept in the house he shared with his sister, Hillary, and Herron. He was actually sleeping in Herron’s bed at the time because after an attack by a group of nationalists on the Short Strand his arm and shoulder were in plaster and his single bed was too small for the cast. Swapping bedrooms cost him his life. Two gunmen appeared at the Herrons’ front door in Ravenswood Crescent, asked for Tommy and were told by his wife he wasn’t in. Refusing to take no for an answer, they pushed their way into the hall and again asked for Tommy. His panic-stricken wife said he was out. One gunman held her in the front hall, put a gun to her head and the other rushed upstairs. He shot the sleeping Michael Wilson in the mistaken belief he was Herron. I was on an errand to the local shop and as I returned to the house saw the two men making their escape. One even got on a passing bus. The police were on the scene in seconds. Hillary was standing in the front garden screaming her head off. The children were running around the garden in a panic and a policeman was trying to catch them. The police wouldn’t let me into the house.

The death of the eighteen-year-old Wilson devastated Herron. Afterwards he went around in a daze. There was speculation that he knew about the killing and even organised it, but I know this to be untrue. The rumour was started by Loyalists in South Belfast who couldn’t wait to dance on Herron’s grave. Before Wilson was even buried, those same men had already hatched a plan to kill Herron himself. I asked him if he wanted retaliation against the IRA for the death of Wilson. I told him it was easily organised. He said just one thing to me: ‘Wrong side, kid.’

Herron now became a stranger to me; he wasn’t the man I’d known. He told me he was resigned to his own death and knew it was only a matter of time before his brother-in-law’s killers caught up with him. He actually excused me from my bodyguard duties, saying he didn’t need me any more. Disappear and keep your head down, he told me. Herron, who never left home without his Star pistol, started to go out without it. He even wandered the streets of East Belfast without security or his bodyguards.

Tommy Herron died in September 1973, three months after his brother-in-law, ambushed by Loyalists on a quiet road in County Down. His body was found outside Drumbo and his legally held firearm was still in its holster. He had taken a lift with someone he knew and obviously trusted. They drove for a few miles but a gunman was secretly hidden in the boot. As soon as the car stopped, the gunman pushed the back seat forward and shot him in the head. Herron didn’t stand a chance. His body was dumped in a lonely ditch and lay undiscovered for days.

Many of his close associates fled to England, America and even Australia, terrified they would be next. I wanted retribution for his death. I started to look for targets and went to Shandon golf course, where arms had been stashed, but the hide had been emptied. I had no weapons. The Braniel unit had run away and I was the last remaining member of the unit that Herron had set up.

I went to Herron’s funeral. The gunmen were there, and the men who organised his execution. The South Belfast brigade wanted Herron removed from the picture and had ganged up on other brigades to get their way. To convince the other members of the UDA’s Inner Council, South Belfast put out a rumour that the American journalist Herron that was romantically involved with was a CIA plant. The rumour took on a life of its own and it freaked out the UDA hierarchy. It was the final nail in Herron’s coffin.

Many years later I was told that the two gunmen were ordered by their brigadier to kill Herron or face death themselves. In the UDA, volunteers did what they were told.