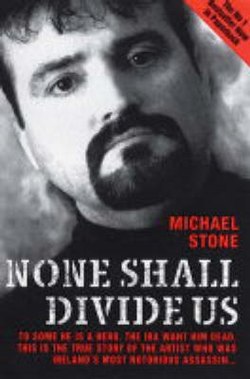

Читать книгу None Shall Divide Us - Michael Stone - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеI FIRST HEARD OF MICHAEL STONE IN MARCH 1988. HIS ATTACK ON THE REPUBLICAN FUNERAL OF THREE IRA VOLUNTEERS SHOT DEAD IN GIBRALTAR IS SEARED ON MY BRAIN.

As a child of the Troubles, for me there are incidents, too many to mention, that stand out for their stark cruelty, their horror and their futility. Milltown is one of them. Although I was young, I could not believe a lone paramilitary would do such a thing. I could not believe a terrorist would gatecrash the funeral of three IRA volunteers killed on active service, but there he was, flat cap and all-weather jacket, lobbing grenades into the crowd and reaching inside his jacket and pulling out a handgun – live on television. I can still hear the crack as the gun was fired, the thuds as the grenades were launched, the sound of women screaming as they grabbed children. I can still see the faces of people as they dived for cover behind gravestones. I remember thinking that nothing, not even funerals, was sacred in the sick, perverted place I called home.

In the days immediately after the Milltown attack the newspapers had a field day about his one-man attack on a high-profile Republican funeral. It took just two days for the UDA, the organisation he joined when he was just sixteen years old, to denounce him. It took just two days for Michael Stone, Loyalist volunteer of seventeen, to lose his identity and become nothing more than labels such as ‘Rambo’, ‘nutter’, ‘loner’, ‘madman’, ‘killing machine’ and ‘robot’ – words used by the print media to describe him. I saw the TV footage and I agreed with their choice of vocabulary. The man was all of these things and more. Only someone insane would even entertain the idea of such a mission.

But sadly the story didn’t end at Milltown. It concluded three days later at the funeral of one of Michael’s victims, IRA volunteer Kevin Brady. Michael’s attack at Milltown was the flame which ignited one of the worst and most barbaric incidents of the entire troubles, the deaths of Corporals Derek Wood and David Howes. The young soldiers served with the Royal Corps of Signals, ironically Michael Stone’s great-grandfather’s regiment, and were executed on waste ground near the Andersonstown Road in West Belfast. The two were attacked by a forty-strong crowd after straying into Brady’s funeral cortège. The crowd attacked because they thought another Michael Stone was attacking them. Republicans heaped on the blame, saying it all went back to Stone’s assault, but to right-minded people it was just another senseless death in Ulster’s war.

I first met Michael Stone in August 2001. He had been released the previous year after serving twelve years of his life sentence for six murders and a variety of other charges, including attempted murder, conspiracy to murder and possession of firearms and explosives. While serving his sentence he began to paint and fell in love with this new pursuit, which gave him expression and focus in his lonely prison life. Within a year of walking from the Maze Prison a free man he had his first exhibition, in a small gallery in Belfast city centre. The work showcased some of his remarkable prison art, painted on the back of bedside lockers and wardrobe doors, and several post-release paintings. It was a proud moment for Michael Stone and his family, but he accepted with a sad heart that most of the people who turned up at the Engine Room Gallery on the Newtownards Road did so for ghoulish reasons. They wanted to see what sort of pictures a murderer paints, what price he sells them for and who in their right mind would have them. Michael caught my imagination.

I did have fears about meeting this man, a Loyalist folk icon revered in song and verse. I was anxious that my opinions of the man, formed twelve years earlier, would compromise my reactions. I made mental notes to be open-minded but I wasn’t prepared for the quiet man who limped down a flight of stairs to greet me; barely able to walk because of the hip injury he sustained in 1988. I was not prepared for the warm handshake that greeted my arrival. I was not prepared for the well-read and intelligent man who enjoys Irish politics and history. I was not prepared for the man who makes a daily superhuman effort to stay alive and admits he is more of a prisoner on the outside than he was inside the Maze.

Most of all, I was not prepared for the man who spoke poignantly about his past as a UDA volunteer and the part he played in the deaths of four men. Nor was I prepared for the man who has the sharpest memory I have ever come across and could recall every heartbeat of his volunteer life with precision. I didn’t anticipate liking Michael Stone, but I did.

To my critics, of whom I expect there will be plenty, I would say just one thing: I do not intend this book to be a glorification of the life of Michael Stone. I do not intend this book to glamorise his life as a paramilitary. The book’s objective is to show what happens to young men, both Protestant and Catholic, who get sucked into sectarian warfare. It is Michael Stone’s story, but it is also the story of a handful of men who lived, and sadly continue to live, similar lives.

Michael Stone’s story is shocking but it needs to be told. It will show him to be more than the tabloid labels, more than Rambo, the volunteer, the killer, the crazed gunman, the prisoner and the artist. This is Michael’s story.

Karen McManus, 2004