Читать книгу Helena Rubinstein - Michele Fitoussi - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

243 COLLINS STREET

ОглавлениеA thirty-year-old woman who was determined to succeed in a city like Melbourne could do only one thing: work. Just like the thousands of other single young women who, in those days, made up more than a third of the workforce.

Melbourne was a new city of over 500,000 inhabitants. Founded in 1834 at the mouth of the River Yarra by two of Her Majesty’s subjects, the city was named after the prime minister, Lord Melbourne. Twenty years later the land of convicts had become a promised land. And the rumour was spreading like wildfire: gold had been found in a river near Ballarat, just 65 miles north-west of Melbourne.

Eastern Australia experienced a gold rush frenzy comparable to that in California and Alaska. From all over the world men armed with picks and shovels disembarked in Port Phillip Bay and headed off to settle in the gold-mining towns that were spreading like weeds. The dream didn’t last long – four years at most – but that didn’t matter. Melbourne had begun to grow exponentially. There may have been little gold but the colonists were raking in money from real estate and finance. They were building churches, offices, cafés, restaurants, hotels and shopping galleries left, right and centre. Wide boulevards were laid out and parks were landscaped. In less than forty years Melbourne became one of the most important cities in the Empire and was known as the richest city in the world. Its stock exchange was as important as that of the financial hubs of New York and London, if not more so.

The economic crisis of 1891 brought a halt to the boundless expansion. Melbourne continued to develop but no longer with the frenzy of its early years. Before long, Sydney, the capital of New South Wales, had overtaken it. At the time of Helena’s arrival, the city inhabited by over thirty nationalities was still known as Marvellous Melbourne, or Smellbourne, after the sophisticated sewer system the city had just installed. Helena marvelled at how modern it all was, far surpassing anything she had ever seen. In comparison, Kraków, Vienna and even Brisbane seemed dreary.

The only cloud on the horizon was the poverty that crippled her. Her savings from the salary she had received from the Lamingtons would be just enough to cover the rent of a furnished room and basic daily necessities while she looked for a job. Without the means to pay for them, she could only daydream about concerts, shows and restaurants.

During the hot summers the people of Melbourne lived outdoors. The women were healthy and muscular from playing tennis, pedalling merrily on their bicycles, and swimming in the sea, modestly clad from head to toe. An Australian swimmer, Annette Kellerman, would soon invent a more revealing swimsuit.

However, despite the protection offered by hats and parasols, the sun still damaged women’s skin, and the winter wind chapped it, leaving premature lines around lips and eyelids. And, like the inhabitants of Coleraine and Brisbane, these city women did little to protect their skin.

As in all the major cities in Australia, novelty was more than welcome. The social system was far more advanced than in Europe. Workers’ rights were respected – the hard-won eight-hour working day had just been introduced. Suffragettes were particularly active. In Sydney, Louisa Lawson, a writer, publisher and journalist, campaigned for women’s rights. Ten years earlier she had founded The Dawn, a monthly journal with an all-female editorial team. Distributed throughout Australia and even overseas, the magazine discussed politics, domestic violence, and girls’ education.

Thanks to the activism of these feminists, most Australian women were given the vote in 1902, four years after the women of New Zealand. Only the Aborigines were left out. They would wait another sixty-five years to be granted full citizenship, even though they had lived in Australia for over 50,000 years.

The role of women in this pioneer country, where life was tough for everyone, was almost as important as that of men. No one found it surprising to see so many young saleswomen, secretaries, journalists, barmaids, chambermaids, waitresses or telephone operators at the brand-new exchange. They earned half as much as their male colleagues, but they were intoxicated by their new independence. Besides, once they had paid the rent, bills and food, they still had a little bit left over to spend on trinkets, silk stockings or cosmetics. And they didn’t refrain from spending.

Helena Rubinstein’s spectacular rise in Australia could also be explained by her innate sense of timing, which, in business, as in love, is essential for success. She was in the right place at the right time, in a country where women were beginning to shake off the fetters that had been imposed on them for so long. In later years in London, Paris and New York, the scenario would be the same: her beauty expertise would keep step with women’s progress. There was nothing frivolous about wanting to be beautiful, and besides, political rights, work, and financial autonomy went hand in hand with an improved appearance. This last point even became an act of resistance. Helena fully understood as much: to succeed in life, a modern woman owed it to herself to have not only a good mind, but also the good looks to go with it.

But for the time being Helena had not given this too much thought. What she wanted above all was to earn money, and quickly. After so many years of hardship, nothing and no one could frighten her, except poverty.

She found a room in a family guesthouse in the suburb of St Kilda, and had no choice but to take up two waitressing jobs, which would just about keep her head above water. She worked at La Maison Dorée in the mornings, and in the afternoon and evening at the Winter Gardens Tea Room, a café frequented by writers, musicians and artists. Up at dawn, she worked like a dog, until her legs were swollen and her feet sore. When at last she returned to her tiny lodgings, well after midnight, she hardly had the strength left to lie down on her bed, where she would drift off the minute her head hit the pillow.

There were evenings when she was so tired that she neglected Gitel’s sacrosanct precepts: brush your hair, clean your face, apply your cream. But no matter how discouraged she became in such moments of extreme solitude and exhaustion, she had no intention of giving up. At dawn she would grit her teeth and head valiantly into the day.

She may have been down and out, but she had chosen her jobs wisely. La Maison Dorée and the Winter Gardens Tea Room were two strategic venues for meeting people. The salary was negligible, even if you counted the tips, but both were places where a clever young woman could easily hook a rich man and set herself up in a fine marriage. In Melbourne, as in Coleraine, men were easily swayed by Helena’s charm. But she wasn’t interested. She nimbly sidestepped any physical overtures.

Among her admirers were four friends who often came to drink a few pints together: Cyril Dillon was just starting out as a painter; Abel Isaacson had made his fortune selling wine, and always wore a fedora and a white silk tie with a pearl tie-pin; Herbert Farrow owned one of the most successful printing presses in the city; and finally there was Mr Thompson, manager of the Robur Tea Company, a firm that imported tea from India and China and manufactured porcelain and silver utensils.

Good-looking and something of a ladies’ man, Thompson showered Helena with flowers. He was married, but she no longer worried about principles. Was he her first lover? She must have got over her prudishness after three years in Coleraine and one in Toowoomba, but Helena remained unerringly discreet on the topic. All four gentlemen served as stepping stones to her extraordinary success in Australia, but she erased them from her own official version: her legend was hers and hers alone.

In the mid 1950s, Helena returned to Australia for the last time with her secretary Patrick O’Higgins; Abel Isaacson, who was still alive, told the young man about the role the four of them had played in Helena’s life. In 1971, when O’Higgins published his book about his employer,1 Cyril Dillon, whose paintings now hung in various museums throughout Australia and the United States, confirmed Isaacson’s story to an Australian journalist. In an interview with the Melbourne Herald,2 he spoke at length about the roles he and the other three had played.

Because she saw them every day, either as a group or on their own, Helena ended up befriending them. The young men were intrigued by her, and questioned her relentlessly until she revealed her ambitions to them. She would start working on her cream the minute her shift ended. She had used part of her wages to buy lanolin and added water-lily essence to give the cream a more pleasant fragrance.

When she talked to them in her broken English sprinkled with Yiddish and Polish, her face lit up and her eyes sparkled. Suddenly she became a determined, confident young woman, who was convinced that life owed her something. They took her seriously and decided to help her, each in his own way. Thompson explained the importance of marketing – a new word to describe the way one could influence the consumer if the product was presented in an attractive manner. The Robur Tea Company regularly bought space in the newspapers to run advertisements, and these had a real impact on sales. Once Helena had manufactured her cream she would have to do the same. Without advertising, you can’t get anywhere, he concluded. Helena would remember his advice.

Cyril Dillon drew her a logo with an Egyptian motif that she used to illustrate her packaging. Dillon was charged with the layout of the first brochures, which were printed by Herbert Farrow. They would hand them out on the trams and in the train stations. Abel Isaacson would help her with the logistics.

A fifth man also entered the scene, Frederick Sheppard Grimwade, the president of a well-known pharmaceutical company. Was he too her lover? Once again, it remains a mystery. But thanks to Grimwade, Helena obtained Australian citizenship in May 1907.3 Acting as a sponsor for his protégée, he signed the document. Better still, his laboratory provided the young woman with sophisticated tools that were indispensable for the manufacture of her cream – receptacles for mixing the ingredients, and cauldrons for high-temperature boiling.

Now known as Valaze, Helena’s childhood cream was at last reborn, almost identical to what she remembered.

The origins of the name Valaze, which rang as sharp as that of a French aristocrat and meant ‘gift from heaven’ in Hungarian, are unknown, but it had instant appeal.

The cream didn’t cost much to make, scarcely tenpence per jar. Thompson, who was also helping with the accounts, thought it should be sold for two shillings and threepence. ‘Women won’t buy anything that cheap,’ declared Helena. ‘When it comes to improving their appearance, they need to have the impression they’re treating themselves to something exceptional. Let’s see … let’s sell it to them for seven shillings and sevenpence.’

She had a perfect grasp of the psychology of her future customers. Not a single one would ever raise an eyebrow at the price tag; they all knew that beauty had a price. Before she had even found the premises for her shop, Helena put her jars on sale at local markets. She also went door to door to pharmacies, and left them with stock to sell. They took six jars the first week, then eight the next … And on it went.

Women bought directly from Helena, too. They enjoyed her banter and the way she wasn’t afraid to cheerfully scold them. The little jars sold like hot cakes. Every penny she took went into a cardboard box hidden under her mattress.

The Winter Gardens Tea Room was located in the Block Arcade shopping gallery which connected Elizabeth Street to Collins Street and Little Collins Street, three of the most elegant streets in town. Built in true Victorian style, the gallery filtered direct sunlight through its glass ceiling. As she came to know the neighbourhood, Helena found a tiny three-room apartment next to the restaurant at 138 Elizabeth Street. In all likelihood, Thompson and Grimwade lent her the money for her security deposit.

Helena also claimed to have borrowed $250 from Helen McDonald, whom she had met on the ship on her way to Australia. Whatever the case may be, she reimbursed her debts as soon as she could, as she hated owing money. One fine morning Helena handed in her waitress’s apron and moved her meagre belongings and jars of cream to her new apartment, which would also be her company headquarters and factory. She immediately had her name engraved on a plaque and put it up at the entrance to the building: Helena Rubinstein & Company.

Shortly before her death, Helena – who had always been evasive about the composition of this initial cream – showed Patrick O’Higgins a slip of paper she had found while sorting through some old files. It was Jacob Lykusky’s famous magic formula. She insisted the young man read it, maintaining it was a page of history.

On the torn, yellowed, time-worn paper were all the ingredients, written down in her large, old-fashioned handwriting, with its carefully executed upstrokes and downstrokes. O’Higgins, who had expected to find a list of exotic ingredients such as oriental almond essence and extract of Carpathian conifer bark, was disappointed. ‘Vegetable wax, mineral oil and sesame.’ That was it, although no doubt half the ingredients were missing from the recipe, and most importantly, so were the proportions in which they were to be mixed.

Right up to the end, Helena Rubinstein would keep the composition of that first Valaze cream a secret, and one can imagine that it had neither the fluidity nor the lightness of the products that came later. But it was full of promise, and had got off to a brilliant start. Thanks to the combined effects of marketing – Thompson’s lessons – and the initial articles devoted to her in the press, sales continued to rise.

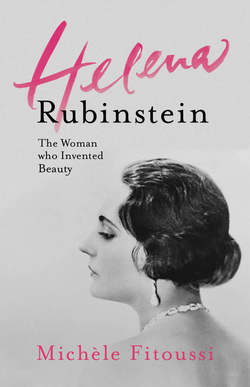

After only a few months, Helena was able to move from Elizabeth Street and in 1902 she opened her first beauty salon at 243 Collins Street.