Читать книгу A Guest in the House of Hip-Hop - Mickey Hess - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеOne

DON’T PUSH IT TOO FAR

I taught a class called Hip-Hop and American Culture, toting my infant daughter in a fabric sling they’ve since outlawed as a suffocation hazard; I fed her from a bottle while I led a discussion on cultural appropriation in popular music. Forty years after the first hip-hop parties in South Bronx rec centers, mine was one of the hundreds of hip-hop courses taught at US universities, from Turntable Technique at the Berklee College of Music to Queering Hip-Hop at Duke. Professors taught courses in the Rhetoric of Hip-Hop, Anthropology of Hip-Hop, and the Politics of the Hip-Hop Generation. The University of Arizona had instituted the nation’s first minor in hip-hop culture. Twenty years after professors wrote their first books on hip-hop—Houston Baker’s Black Studies, Rap, and the Academy, Tricia Rose’s Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture—Hip-Hop Studies was thriving.

I joined the English Department at Rider University in New Jersey as America prepared to elect its first black president, Barack Obama. Somebody wrote “nigger” on the wall of one of our dormitories. Sixty miles north, at Columbia University, somebody hung a noose on the door of a black professor. Two white reporters from our student paper came to my office toting a Halloween costume—a “Rap Star” complete with fake gold chain and fedora—hoping I’d wear it for the photo they’d run with their story on my class. I did not put on the costume. A white professor dressed up like Run DMC symbolized everything I feared could go wrong with a university teaching hip-hop; the fact that these two eighteen-year-olds didn’t see it convinced me I might do some good.

I scrounged around campus for money to pay guest speakers, determined to let no student of mine exit a rap class without having sat in a room with a rapper. I pieced together a 300-dollar speaking fee for a man who’d toured the world performing with the Wu-Tang Clan; he asked if we could pay him in cash so he wouldn’t risk messing up his public assistance. I brought in a childhood hero of mine, an old-school MC who sent me a last-minute request for an extra hundred dollars to pay his driver but then showed up alone, behind the wheel of a beat-up old borrowed car.

It paid better to teach a rap class than to rap, and how did we vet the professors? None of us had a PhD in Hip-Hop, after all; our degrees ranged from English to Architecture. We could have known nothing about rap music beyond how to use it to pack classrooms by pandering to our students’ interests, and rappers suspected as much. The legendary hip-hop producer Prince Paul smiled and shook my hand when I picked him up from the New Jersey Transit station, but I watched his eyes light up in my car on the way to campus when I asked him about an obscure De La Soul b-side he’d produced. “Wow,” he said. “So you’re really an old hip-hop head, huh?” Paul wasn’t the first guest speaker to express surprise that I knew the subject I’d been hired to teach. It puzzled me, at first; nobody would question if a physics professor were, you know, really into physics. Then I remembered that white people are so prone to steal—that’s how we ended up with a rapping Pillsbury Doughboy—that it wouldn’t surprise a rapper at all to see a rap class taught by a white professor who didn’t know the first thing about rap. Never mind Miley Cyrus twerking on MTV; this scheme goes so far back that white people took the Charleston from black people. White people stole the banjo—an African instrument—so conclusively that if today, in America, you said, “I know a guy who plays banjo,” no one would picture a black person.

I didn’t exactly exude hip-hop. Bouncers, as I approached a rap club, once asked me if I was lost. I once invited one of the most important women in hip-hop to campus and when I met her in the parking lot she awwed like she’d met an eight-year-old boy who taught a class on rap music. Was I so harmless as to inspire an aww, even though I was a white guy teaching a class on a music genre where many of the corporate moguls signing the checks remained white as ever and the black artists were still going to jail for the stories they sold in songs? In a country built on such a pattern of theft, I was full of myself to believe that one man teaching one class could do much good or harm. Standing behind the lectern, I looked like comedian Irwin Corey’s bumbling old white professor pausing to define rap music at the beginning of Run DMC’s “Rock Box.” I looked like Spalding Gray’s militant white professor goading Redman and Method Man to boycott his Black History class in their comedy How High. I looked like Fordham professor Mark Naison in his subtly self-deprecating turn as a white contestant on Dave Chappelle’s trivia game-show spoof “I Know Black People.” A white man teaching Black Studies: was it funny or tragic?

•

No matter how many guest speakers I brought in, my course was still designed and taught by a man rappers might mistrust. In 1993, in my first year of college, I sang along with De La Soul—“White boy Roy cannot feel it/but he’s first to try and steal it/dilute it/pollute it/kill it …” In 2016, I nodded along with Vince Staples—“All these white folks chanting when I ask them where my niggas at”—while Kanye West asked white people to please stop writing about hip-hop.1 Rappers welcome money from white fans, but they’ve always expected whites would someday take hip-hop away from them. Faced with Vanilla Ice in 1990, music journalist Havelock Nelson wrote, “Rock-and-roll was black back in the days when it began … I don’t know if rap in the year 2050 will be seen as white. But it damn sure could be.” I didn’t believe it could happen, but now, halfway to 2050—with Iggy Azalea, and Tom Hanks’ rapper son, and the scores of Scandinavian rappers—I’m starting to worry he may have been onto something.

The catch-22 for white rap fans is that deeper participation tends to look more suspect. It’s more okay to be a white guy who recognizes Jay-Z from pictures in People magazine than it is to be a white guy who wants to parse Jay’s lyrics and publish a book. Yet backing away from black culture seems too easy a solution. After all, white people have been ignoring black culture for years. It’s a problem that Elvis Presley got famous singing songs black artists had already recorded, but it’s a bigger problem that so many Americans never heard those songs until Elvis sang them. An older white professor once clapped me on the back and, with a condescension that said I’m so racially enlightened I avoid black art entirely, cracked a joke about a white guy teaching a rap course. He made jokes but I bet he couldn’t name ten rappers. Could he name ten black novelists? At one extreme, nobody wants an African-American Studies department staffed entirely with white professors. At the other, nobody wants a white professor to leave James Baldwin off her American Lit syllabus because she thinks white scholars shouldn’t teach black art.

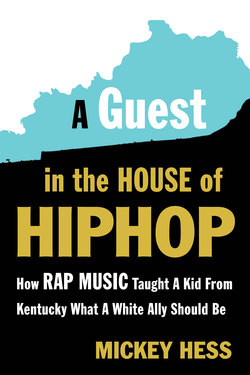

White people shouldn’t hide their silence behind the lofty ideal of avoiding cultural appropriation, but they also shouldn’t speak on black issues with a casual overfamiliarity. Ice Cube called his white fans eavesdroppers, but added that “even though they’re eavesdropping on our records they need to hear it.”2 Lord Jamar called white rappers houseguests. Macklemore used a song to promote tolerance—“If I was gay, I would think hip-hop hates me”—and Jamar took offense: “Okay, white rappers … you are guests in the house of hip-hop. Just because you have a hit record doesn’t give you the right, as I feel, to voice your opinion.”3 I found myself wanting to agree with Lord Jamar, a rap legend I once saw share a bill with Nice & Smooth on the deck of the battleship USS New Jersey. But I can’t agree entirely when I get paid to voice my opinion. I wouldn’t be much of a professor if I never said anything critical of my subject. I can’t agree entirely when he’s essentially complaining, We let a white guy into the party and he said we should let in gay people too. “Don’t push it too far,” said Jamar. “Those of y’all who really studied the culture, that truly love hip-hop and all that, keep it real with yourself, you know this is a black man’s thing.” (Notice he said black man.) The paradox for the white hip-hop scholar is that to know hiphop culture means to know it doesn’t always welcome criticism from white professors.

For me to accept this paradox is not to buy into the tired old nonsensical claims of “reverse racism.” First, the very fact that white people have to call it reverse racism reaffirms the direction the violence has flowed. There is no reverse bullying, reverse terrorism, or reverse rape. Second, it is not “reverse racism” when a white professor makes his living teaching a course on a black cultural form where some of the black musicians say they’d prefer whites step aside. Lord Jamar doesn’t exclude white people—the ones who’ve done their homework, at least—from participating in hip-hop; he just doesn’t want to see a white guest walk into hip-hop’s house and start changing the wallpaper. I imagine he’d approve of my taking a class in hip-hop, but tell me I sure as hell shouldn’t teach one. Michael Eric Dyson—one of the black scholars whose books I assign as required reading—sees a much bigger problem than one person leading one classroom. “I’m not saying,” he writes, “that non-black folk can’t understand and interpret black culture. But there is something to be said for the dynamics of power, where nonblacks have been afforded the privilege to interpret and—given the racial politics of the nation—to legitimate or decertify black vernacular and classical culture in ways that have been denied to black folk.” In other words, it’s not only about how well the professor knows hiphop; it’s about who approved the curriculum and gave that professor his job. My personal experience illustrates Dyson’s point: I wrote a doctoral dissertation on hip-hop that was approved by a committee of four white men and one black woman; I’ve published four books on hiphop but never been assigned a black editor. My work has, of course, gone through the anonymous peer-review which is the foundation of academic publishing, so I can hope—but not assume—some of the unnamed readers who voted to publish my writing were black scholars who specialize in the study of hip-hop. But it’s no stretch of the imagination to believe that a white man could become a credentialed and published expert in a black cultural form without ever having a black person check his work.

American universities offer hundreds of hip-hop courses even as they employ embarrassingly low numbers of black professors—only around six percent of university faculty nationwide. I hope we are facing a sea change and that six percent will soon double and triple—there is certainly some momentum to the call for more black professors—but hiring more black faculty members won’t, on its own, correct an imbalance of power that is about more than percentages. Critic Alex Nichols, writing about the musical Hamilton, rejected the notion that filling more roles with black people solves racial disparity: “Contemporary progressivism has come to mean papering over material inequality with representational diversity. The president will continue to expand the national security state at the same rate as his predecessor, but at least he will be black. Predatory lending will drain the wealth from African American communities, but the board of Goldman Sachs will have several black members. Inequality will be rampant and worsening, but the 1% will at least ‘look like America.’ The actual racial injustices of our time will continue unabated, but the power structure will be diversified so that nobody feels quite so bad about it.”4 Electing a black president didn’t end racism; rather, the prospect of his election brought out the hangman nooses to a Selma, Louisiana schoolyard and the campuses of Maryland and Columbia, and his two terms inspired racists to run for office. If history teaches us anything, it’s that a boom in black professors will probably prompt a similar backlash. Race in America is more complicated than black vs. white, although every time we think we’ve moved beyond that binary something drags us back into the past.

Of course universities need to hire more black professors, and I can’t disagree with the assertion that black scholars should lead the discussion about black culture and vet the white scholars who research and teach that culture. White scholars studying hip-hop should first and foremost listen to black rappers and scholars, but to stop at listening alone is a cop-out. I worry that plenty of white professors would be happy to hire new black professors and direct minority students to them and leave matters of race to be taught in their classrooms so that the white professors don’t have to risk saying the wrong thing. Race permeates every subject; the university shouldn’t delegate to newly hired black professors the responsibilities of confronting race in the classroom.

But even though white professors can’t shirk the responsibilities of discussing race, we could read hundreds of books by black scholars and it still won’t completely wear down the edges of our blinders. Vetted by peer review or vouched for by rappers, a white scholar remains an outsider. I’m never all that satisfied with the self-justifications of the other white scholars, and I’m by no means looking to inspire a new legion of white people to become hip-hop professors. Yet I stand firm in my conviction that I’m a white person doing it well—even if the best way I know to do it is to keep questioning that conviction. I am undeniably part of the forces taking hip-hop further away from its roots, into college classrooms and onto library shelves. I know my hip-hop, but I don’t know how it feels to be black in America, so it would be grossly irresponsible for me not to ask my students to think about the problems and contradictions inherent in what their professor does for a living. But I haven’t quit teaching yet, so I don’t want to sound like I’m going through the motions of making excuses. Saying I know my history—even if it might look like I’m only repeating it—might come off as a self-serving and insincere gesture. My self-examination has to allow for the real possibility of my being wrong; otherwise it’s only a show I put on for my critics. But I can’t say I’ve studied hip-hop for this long just to reach the conclusion that I shouldn’t be doing it.

I’ve been teaching hip-hop in colleges for fifteen years, after all. Having recently turned forty-two years old—almost as old as hip-hop itself—I’ve become keenly aware that my students were born after Tupac was already dead. I am a forty-two-year-old white man who makes his living studying music created by black youth, and my course feels more and more like a history lesson. I can hustle to keep up with the new rappers, but I’ll still never quite get it. I’ll never hear the new songs the way a twenty-year-old hears them. It’s a harsh realization, but worse is its corollary: if I can get too old to write about hip-hop, was I always too white?