Читать книгу A Guest in the House of Hip-Hop - Mickey Hess - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThree

“IT’S ABOUT CLASS, NOT RACE”

(NO, IT’S NOT)

Americans are tied to the idea that we’ve earned what we have. I belong here because I fought hard to get here, say the rappers and the politicians alike. It is our American mythos of overcoming the circumstances of our birth and escaping the place we came from, our American dream that a kid from Kentucky, no matter the hopelessness of his neighbors, can “one day leave those worthless hicks behind while still using their story to enhance my own credibility.”1 America tells me the stories I was most ashamed of growing up should become a point of pride now that I’ve made some money, that the value in these experiences is in looking back at them to congratulate myself on how far I’ve come. It benefits me to use these stories to brand myself a particular kind of white who still had things easy but not as easy as the white people who grew up rich. But having grown up on food stamps doesn’t qualify me to write about hip-hop, even if it does affect the way I look at its stories of rising out of poverty to buy your mother a mansion.

The more I read and write, the more I question the role of my race in relation to my subject matter. I used to find some solace in the fact that I’d spent more on hip-hop than I’d made from it, but with the hiphop class paying a piece of my salary that is likely no longer the case. Not to say I’m getting rich. I’m not making money like Lyor Cohen or Jimmy Iovine, the white record executives who’ve made millions from hip-hop. Tuition has skyrocketed, but students’ dollars haven’t exactly ended up in their professors’ pockets; by one estimation, tuition rose 72% more than the rate of inflation between 2001 and 2011, while faculty salaries at the end of that decade stayed right where they were when the decade began.2 Still, the money was good enough to lure me away from Kentucky for a move to my job at Rider. My wife and I rented an apartment in nearby Philadelphia, in a neighborhood where the tattooed twenty-somethings lived their lives like Kentucky grandmothers: they make and sell beeswax candles and butterscotch pies; they weed rooftop gardens and run knitting workshops. Many of them had degrees from elite colleges, but weren’t putting them to any vocational use other than to lean on theories they’d learned about late capitalism to rationalize their conviction that people should know how to make something other than money.

When faced with the birth of our first child, my wife and I turned to the Internet to ask where we should raise her. Our search began logically enough, with the Philadelphia Inquirer’s Murder Map and the National Sex Offender Registry, but—scared out of Philly—we found ourselves studying the standardized test scores and median household incomes of the South Jersey suburbs. How quickly the Internet presented me a pie chart of the racial makeup of each school. I’d like to picture a Mexican-American family seeking this information to assure their daughter she won’t be the only Chicana in her class, but I know it’s probably white people using it to make sure the whole school looks just like them.

I see myself as the kind of person who’ll send my daughter to public school. Philly schools were bad, so I moved to the small town of Haddonfield, New Jersey, where the schools were good. Friends of mine see themselves as the kind of people who live in the city; they want their daughter to grow up around diversity, so they stayed in Philly and sent her to a pricey private school where she met her best friends, that diverse body of kids whose parents can afford to send them to a pricey private school. Another couple I know found a lower tuition rate at a Catholic school, so they send their kids there, even though they aren’t Catholic and don’t want their kids to be. What a lot of effort we expend to protect our children from the other children whose parents can’t afford to choose where to send them to school.

Where we live is who we are, or at least who we look like to other people. I have set aside aspects of my identity in order to live in a small town where the schools score high on standardized tests I don’t even believe in teaching to. When I told a friend I was moving to Haddonfield, he frowned and asked, “But aren’t they all Republicans?” A whole town of Republicans: the prospect frightened me. What would they be like? What would they do to my daughter?

I’ve never voted Republican. I’ve barely voted at all, considering the countless opportunities I’ve ignored in state and local elections. But as an eleven-year-old boy in Kentucky I wore a T-shirt with Ronald Reagan drawn, boardwalk-caricature style, as an Old West gunslinger: sheriff’s badge, sagging holster, spurred cowboy boot kicking the ass of a turban-headed Muammar Gaddafi. The shirt was an adult large, big as a nightgown on me, but I begged my mother to buy it. “Why?” she asked. I had never expressed an interest in politics. My knowledge of President Reagan came almost entirely from “Ronnie’s Rap,” a novelty record I played incessantly. One verse, in particular, made me laugh:

Met with Gorbachev in ’85

To talk about how everyone could stay alive.

And though he seemed to be a guy with class

If he doesn’t play ball, we’ll nuke his … country.

I begged for the Reagan shirt. Mom bought it for me on the condition I would not wear it to school, but I wore it anyway, the very next day. The gym teacher gave me a wink and a furtive thumbs-up. “How come you’re wearing that Ronald Reagan shirt?” my friend Scott Hurt asked. I didn’t know. There were two shirts for sale and I chose one.

“Democrat or Republican,” said my dad, “all of em’s crooks.” He shook his head at my Reagan shirt and told me the last vote he’d cast was for Richard Nixon, so he’d never vote again. We are all voting for crooks, yet we see ourselves as very different from a person who chooses the opposing crook. At what point did I come to hear Republican as a slur?

A Haddonfield neighbor who grew up in Georgia told my wife and me she was happy to see some more Southerners. I felt a tinge of pride at being so warmly called a Southerner, same as I’d felt insulted at the suggestion I would join the Republicans. Although I’ve never claimed either label. Although I once spent an hour trying to convince a near-stranger that Louisville was more Midwestern than Southern. He had written off the South so conclusively that it seemed easier for me to redraw the map than to change his mind. It’s a rare New Jerseyan who doesn’t see my leaving Kentucky as a move toward success. Mostly they congratulate me for having left the land of red-state Republicans. And now I’ve stumbled onto an exclave.

But if I can move to a garbage town, or a garbage state, what’s to say I can’t live in a garbage country? Our national elections are neck-and-neck races, each side certain the other is wrong, so most of us must believe America is 50% awful. Where do we draw the lines: Democrat vs. Republican? Rural vs. Urban? North vs. South? White vs. Not White? Rich vs. Poor? I like my news blunted by comedy; my mother likes hers panicked as a horror film trailer. You may not have much, her news tells her, but people less deserving are coming to take it; if the government would stop helping them take what’s yours, you might have been rich by now. My news makes fun of her for being so easily fooled. Mine tells me the rich—not the poor—are the villains, and I believe it.

I once saw a free concert—a rap group called Black Landlord—in Philly’s Rittenhouse Square and cheered along with the rest of the crowd when the MC pointed up at the expensive high-rises surrounding the park and said, “Fuck all those rich people up in them towers.” Weeks later, my department hired a new English professor and he moved right into one of those towers. He was no richer than I was. I was no less rich than he was. Yet I look at the people with houses bigger than mine and I harbor the illusion they do not deserve what they have. They were born rich, I tell myself. Or if they worked for it, they worked too hard, traded their lives for money, made a deal with the devil. Do I deserve what I have? Books about rap music bought me my house. Things could have gone very differently.

•

My Haddonfield neighbors convince themselves they’ve earned what they have and that they’re teaching their kids that hard work—not inheritance—will earn them a large home in a nice neighborhood. They assume I got here not only by hard work, but a legacy of it. “My father got up in the morning and put on his suit and went to the office,” a neighbor proclaimed. “I see people on food stamps and they’re perfectly happy to sit at home all day and wait for their handout to come in the mail. What kind of lesson is that for their kids? I mean, what did you see your dad get up and do in the morning?”

I saw my dad trade twenty dollars in food stamps for ten dollars in cash so that he could buy cigarettes. I saw my dad pull his own wisdom teeth with a pair of pliers and a bottle of Old Granddad. We didn’t have health insurance. My sister broke her arm when she jumped through our backyard sprinkler and landed on a beach ball; Daddy wanted to set it at home. I saw my mom, when she went to take a sip of her Pepsi, stop short and hold the bottle up to her eye like a pirate’s spyglass to make sure no roaches had crawled inside. Roaches infested our cabinets so we kept cereal boxes inside an old Styrofoam cooler on the kitchen table and stored our dishes inside our broken dishwasher. Fake brick paneling in the kitchen. Fake wood grain in the living room. What were we trying to hide?

Coalminers and war veterans on one side, farmers and schoolteachers on the other. My mom’s family made its living growing tobacco, the poison that killed my dad. The Japanese captured Papaw Hess during World War II and starved him until he was hungry enough to strangle and eat the chicken they tossed into his cell. He came home from the war different, I was told. Burned his son’s toys in the heat stove, laughed at him for carrying a baby doll, like a girl, until Daddy, seven years old, finally took an axe and chopped off the doll’s head. Daddy started smoking before he was ten years old, quit middle school to learn to rebuild cars. He spent months restoring a 1955 Chevrolet and, while he was serving in Viet Nam, Papaw sold it and spent the money.

Having taken his share of orders in the Air Force, my father refused to work for any boss but himself. He was too stubborn to look for a better-paying job painting cars for one of the lots down the road in the bigger town of Somerset. He played country guitar at late-night parties and slept through AM appointments while Mom dealt with customers. If it was a potential new paintjob, she’d pray they called back. If it was a friend or neighbor seeking a quick repair, she’d invite him into the house to try, himself, to shake Daddy awake. One morning, a man Mom knew from church stopped by and claimed he’d already paid, so she gave him his keys and he drove off with all Daddy’s hard work. When Daddy finally got out of bed and saw the car gone, he drove around town, raging, until he spotted the car parked in front of the Science Hill pool hall. He took a tire iron out of his trunk and smashed every part of that car that he’d fixed.

Daddy wasn’t home much and when he was he was in the body shop working and avoiding his family. I stayed in the house where I could watch TV and avoid him and his friends and the cars they worked on. I took Mom’s side because she talked about her side and he didn’t talk much. When she tried to talk to him, he broke a chair over the kitchen table. She asked her brother to talk to him, his brother to talk to him, but he would not listen to anyone. We were his wife and kids and he lived with us, but he also lived with some woman in a trailer behind Oran’s truck stop. When my dad was at home, I remember him most for his anger at me and my sisters for having woken him up watching our Saturday morning cartoons. He’d stomp through the kitchen to stir Folgers Crystals into a cup of microwaved water and sit silently at the table looking tired and introspective and put-out. He’d smoke a few cigarettes and then paint cars until it was time to play music again. Back home at 2:00 AM, still on a performer’s high, he’d brew a pot of coffee and paint some cars and finally go to sleep. He’d lie in bed until late in the afternoon, screaming, “Shut them kids up! I can’t take it.” He’d peel out of our gravel driveway and mom would say, “Well, you ran him off again. I hope you’re happy.”

My mother felt as tied to our house as my dad felt imprisoned by it. She told me I was going to go places in life, but she was scared to let me leave the front yard. She shook her head at the prospect of traveling an hour’s distance to take me to watch the Harlem Globetrotters at Lexington’s Rupp Arena, named after an old racist who never wanted to let black people play basketball. “I don’t know how to get there,” Mom would explain. “And even if I could get to Lexington I wouldn’t know how to drive once I got there.” She was comfortable driving only to places she’d already driven, and only until dusk, when she said her night blindness became too severe to drive anywhere at all. We left my friends’ autumn birthday parties before the cake, Mom wringing her hands and mouthing prayers that we’d make it home before nightfall. Back home, safely, she sat in her recliner underneath an electric blanket, her upper lip shiny with Vicks Vapo Rub, her eyes red and watery, toilet paper wadded in her fists and stuffed between the cushions, and anti-anxiety meds and a can of caffeine-free Pepsi on the floor beside her. “He’s not coming back this time. I just know it.”

My father didn’t want to be an auto-body man with a wife and three kids. He was good enough at guitar to believe it should make him famous. He wanted to be on stage at the Grand Ole Opry. And when my sisters or I pled for a trampoline or cable TV, he’d say, “Well we don’t always get what we want, do we? I wanted to be a famous guitar player.”

It wasn’t enough to be famous in small town Kentucky, to play Saturday nights at his friends’ pig roasts and Sunday afternoons at the flea market. He wanted to be on television, so he hated the guitarists he saw on TV. I listened to him blame the stars for being more good-looking than talented, for having it too easy, for knowing somebody. He didn’t say much, but I latched onto the bit he said: things were unfair.

•

I saw white resentment of black success when I stayed up late to watch Saturday Night Live. Daddy and his friend Kenny watched me watch Eddie Murphy put on makeup to pass as a white man—a satirical reversal of the social experiment from Black Like Me, a book I’d seen on my teacher’s shelf. “Slowly I began to realize,” said the white Eddie Murphy, “that when white people are alone they give things to each other for free.”

Kenny shook his head. “Shoot, ain’t nobody ever give me nothin. Have they you, Mike?”

“They sure ain’t,” said my dad. “They wouldn’t give me air if I was in a jug.”

Kenny’s was a common resentment among the adults I knew: they resented that black people had cornered the market on pity; they resented that black people were free to assume white people had it easy by virtue of being white, even as black people had also—somehow, after centuries of being subjected to the offhand vitriol of whites—cornered the market on taking offense to jokes about race. In 1961, less than twenty-five years before I watched Eddie Murphy on Saturday Night Live, Dick Gregory—one of the first black comedians to regularly perform for white crowds—joked, “Segregation is not all bad. Have you ever heard of a collision where the people in the back of the bus got hurt?” In 1961, the joke was on segregation. In 1984, the joke was at long last on white people.

I laughed as the white Eddie Murphy sat, stiff and pale, as the last black man exited a bus and the remaining passengers—all white, or so they thought—began to sing and dance, free at last from the burden of his presence. I laughed at Eddie Murphy, in another SNL sketch, playing a grownup Buckwheat from the Little Rascals, mispronouncing the lyrics of popular songs. “Shoot,” said Kenny. “He don’t even know he’s making fun of himself, does he?” Buckwheat kept mispronouncing lyrics. “Well, that’s a nigger for you, ain’t it? Hell, I can’t stand ’em, can you, Mike?”

And Daddy said, “Aw, now I reckon some of ’em’s okay. There’s good ones and bad ones, same as us.” He believed that—or I choose to tell myself he did—but I watched him set aside his convictions to make a joke. I watched him get big laughs in our kitchen on Martin Luther King Jr. Day—the first one our school district had deigned to observe; Kenny asked why I was off school and Daddy shrugged and grinned and said, “Some nigger’s birthday.” Listening to him, I learned that it was okay to make jokes as long as you didn’t mean it. But as irresponsible as he was in leaving me with that lesson, I still find myself wanting to defend my dad, to say he dropped out of school in the eighth grade, didn’t have the advantages of a higher education, grew up in racial isolation in rural Kentucky, or was just joking. White Americans have spent so many decades making these kinds of excuses for our ancestors, and devoted so little time to trying to distinguish the jokes from the threats, or to ask ourselves if there was ever any difference at all.

I heard the word “nigger” as frequently in my dad’s body shop as I did on my N.W.A. cassettes. When presented with a repair estimate, a customer might respond, “Well, I ain’t got the money to fix it right, so I reckon we’ll just have to nigger-rig it.” To barely fix a car was to “nigger-rig” it, but to make a car look too flashy was to “nigger it up,” e.g., “My cousin put ground effects on his pickup, but it just looks too nigger for me.” Black people couldn’t win.

My teachers and church deacons clung to the stereotype of the young black male criminal, but they didn’t like to see young black males getting rich rapping about being criminals. They told me rappers were not as poor as they claimed to be—if they were really from the street they wouldn’t even get past security to sign a record deal. It was all exaggeration, they assured me. The white grownups around me made jokes about black people using food stamps and stealing hubcaps, but they didn’t like to see them use crime or poverty as a means to succeed. “Just look at them waving their guns and their gold chains around,” they might say. “Martin Luther King would be ashamed of them, the way they act.” White people kept buying songs and movies that told those stories—the desperation of drug-dealing, the power of the gun—even as they used those same stories to keep black people right where they were.

White rock bands sued rappers for stealing little slices of sound, after all the moves rock bands had stolen from black guitarists. White rappers stole stories about growing up poor and desperate so that their biographies fit some stereotypical sense of what it meant to be black. White rapper Vanilla Ice outsold any rapper to come before him, his promotional materials presenting a “colorful teen-age background full of gangs, motorcycles and rough-and-tumble street life in lower-class Miami neighborhoods, culminating with his success in a genre dominated by young black males.”3 Black journalist Ken Parish Perkins pulled Vanilla Ice’s high school yearbook from the Dallas suburb of Carrollton, Texas—1,300 miles from Miami—and called Ice’s manager to question the contradiction. His upbringing “could have been well-off,” said his manager, “but maybe he chose to go to the street and learn his trade. When he said he’s from the ghetto, it may not be true that he grew up in the ghetto—but maybe he spent a lot of time there.”4 Makes sense. If there’s one thing rap tells us the ghetto welcomes, it’s well-off white kids dropping by for apprenticeships. “If you ain’t never been to the ghetto,” warned Treach of Naughty by Nature, “don’t ever come to the ghetto. Cause you wouldn’t understand the ghetto. So stay the fuck out of the ghetto.”5

Ice’s lies might have struck a nerve with Perkins, a black man who’d grown up in the kind of neighborhood Vanilla Ice only visited. One of the few black journalists at the Chicago Tribune, Perkins rejected the paper’s plan to publicize his rise from the housing projects to the Tribune newsroom in order to promote its commitment to diversity. He refused to allow the paper to publish his photograph with his column; “[Readers] see a black man,” he reasoned, “they think he’ll be a certain way.”6 A black journalist hid his face and his life story from readers, even as he exposed a white rapper for faking his life story to appear something closer to black. A black journalist brought down a white rapper for having stolen his struggle story from his black peers, but when it came to presenting his own struggle, he preferred readers assume he was white.

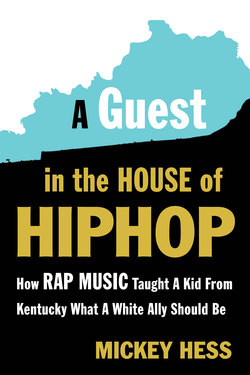

A white rapper cribbed his struggle story from black rappers and outsold any rapper before him. When black rappers complained, he tried to turn the backlash into a struggle in itself. “People are out to bust Vanilla Ice,” his publicist Elaine Schock told the Philadelphia Inquirer, “because he’s successful and because he’s white. I do think it’s reverse racism.”7 Was it, though? Vanilla Ice was a guest in the house of hiphop and he sneaked out with a piece of its foundation and stood on it to reach the top of the pop charts. Facing the backlash, Ice brought Public Enemy’s Flavor Flav with him to his interview on The Arsenio Hall Show, but his strategy backfired when Hall asked Flav to wait offstage while he took Ice to task. “A lot of black rappers,” he said, “are probably angry because some of the white people screaming [for you] didn’t buy rap until you did it, until they saw a vanilla face on the cover of an album.”8

“You saw Flavor Flav. Me and him, we’re homies,”9 Ice asserted, although only moments earlier he’d received the man’s handshake so awkwardly it looked more like they’d met for the first time ever right there on stage. “Is that why you brought him out? Just to show you have a black supporter?” asked Arsenio.10 I was fifteen years old when I watched this interview air live on Arsenio Hall, and it was the first time I felt like rap didn’t belong to me; I’d discovered it, after all, on that hike through the woods to Wolf Creek Dam. Now, re-watching the clip when I’m forty-two and preparing to teach a lesson on white rappers, I have to ask myself this question—when I bring rappers as guest speakers, how pure are my motives? I’m dedicated to having students talk face-to-face with rappers, but I can’t deny that I also mean to enhance my own credibility by making my course look legitimate enough that a rapper would drop by.

Vanilla Ice positioned himself as an anomaly among white people, telling Hall he was the unicorn among “the majority of white people” who “cannot dance.”11 Being white and thus rhythmically disadvantaged, Ice suggested, had made succeeding even harder for him, yet he overcame biology to develop an undeniable skill that sold records and concert tickets: “People who said I never could make it, that I’d never amount to S-H-I—you know the rest—said a white boy can’t make it in rap music, kiss my white … you know the rest.”12 Once it came out that he’d exaggerated his link to the ghetto, fans were less willing to take his word on his skills as an artist. Perkins exposed Ice’s lies, but Ice’s fans were at fault for finding his fake story compelling. Why were listeners so eager to hear about a white man who’d ventured into a black neighborhood and outshined the black musicians?

Vanilla Ice was so thoroughly discredited that for the next ten years, any emerging white rapper was haunted by his inauthenticity. No rapper wanted to look like another Vanilla Ice. House of Pain wore shamrocks and Celtics jerseys in a sort of racial rebranding effort. We’re not white, these symbols suggested; we’re Irish. The group’s frontman, Everlast, had released a solo album just two years earlier and never said “Irish” once, yet his House of Pain album included “Top O’ the Mornin’ to Ya,” “Danny Boy, Danny Boy,” and “Shamrocks and Shenanigans.” The Irish, who endured indentured servitude but never the chattel slavery that brought Africans to the Americas,13 had endured social and economic exclusion in the US at the hands of other whites, but that exclusion was very much in the past by the time House of Pain’s hit single “Jump Around” reached number 3 on the US charts, and number 6 in Ireland.

Not until 1999, nearly a decade after Vanilla Ice, did another white rapper reach (then exceed) his level of sales and fame. Eminem convinced listeners that not only did he really, truly grow up poor in Detroit, but Vanilla Ice had made things even harder for him by making white rappers look like liars. 8 Mile’s most powerful scene shows Eminem’s character B. Rabbit win a freestyle battle by revealing his black opponent, Papa Doc, is not who he appears to be. Rabbit disarms Doc by owning up to living in a trailer with his mom—“I’m a piece of fucking white trash, I say it proudly”—as he accuses Doc of posing as something he’s not:

I know something about you

You went to Cranbrook, that’s a private school.

What’s the matter, Dawg, you embarrassed?

This guy’s a gangster? His real name’s Clarence.

And Clarence lives at home with both parents.

And Clarence’s parents have a real good marriage.

The revelations rendered Doc mute, but I imagine that late that night, tucked into bed, he might have thought, Yeah, but a cop would still shoot me first.

If Doc could have thought faster on his feet in the battle, he might have put into rhyme the notion that when strangers see him they see a black man, rather than a man with a private-school diploma. Why do you think the crowd was so willing to believe I was a gangster, he could have asked Eminem’s character, and so unwilling to believe you’ve faced a struggle?

White rappers try to shift the discussion from race to class, as if the wealthiest boardrooms and schools and neighborhoods had not been designed to keep black people out, while ghettoes and prisons were designed to keep black people in. When I tell stories about my childhood, I don’t mean to suggest that class trumps race, or that food stamps even the playing field. My parents, unlike Clarence’s, didn’t have a real good marriage, but that doesn’t make me less white. Eminem certainly admits being white made it easier for him to sell platinum; he attends to the advantages white skin gave him in selling records to white fans who might not have owned one song by a black rapper: “See the problem is/I speak to suburban kids/who otherwise would have never knew these words exist … they connected with me too because I looked like them.” Yet Jimmy Iovine, the record exec who signed Eminem, claimed hip-hop had so torn down racial binaries in this country that 8 Mile was “about class, not race.”14 “A white label head,” responded Public Enemy’s “media assassin” Harry Allen, “discusses a movie, ostensibly about a Black art form, in which the lead character is white, the screenwriter is white, the director is white, the producer is white, most of the productions talent, no doubt, white, and, of course, the film itself owned by a company run by, mostly owned by, and deriving the majority of its income from white people. Yet, something or other is ‘about class, not race.’”15

Eminem’s childhood poverty was so verifiable that he could put his childhood home, at 19946 Dresden Street in Detroit, on his album cover. Eminem’s old neighborhood was so impoverished that in 2013, the Michigan Land Bank put the house up for auction, with bids starting at only one dollar, despite the house’s fame. A reporter dropped by for a firsthand look at the place Eminem grew up: “A man who lives on Dresden,” he wrote, “told me that the neighborhood has been terrorized by drug and gang activity for several years. He also mentioned, while walking a 200-plus pound pit bull on a choke chain, that I should be careful because dope dealers often prey on Eminem fans who stop by and visit the home.”16 A white rapper found success in a genre invented by black men; his old neighbors menaced his fans. The fans came on a pilgrimage, determined to see for themselves the unsafe neighborhood and the crumbling childhood home that had made the white rapper who he was. You’d think one of them might have put down a dollar to purchase the house, but before it could sell, it burned down. Eminem’s employees recovered bricks from the rubble and sold them to fans via his website.

Just across town, Ben Carson—a black, Yale-educated surgeon—was running for president. In a 2015 campaign video, he posed in front of a dilapidated house much like the one Eminem put on his album cover. “Poverty and the mean streets of Detroit could have defined my life,” he said. “I’m Dr. Ben Carson, and this is my story.”17 That was his story, maybe, but that wasn’t his house. Reporters traveled to the house where Carson actually lived as a child and a teenager, and found that it “sits on a tree-lined block of well-kept, middle-class houses.”18 Carson’s childhood neighbor, who still lives on the same block, said, “This has always been, I would say, a pretty decent neighborhood—people working, kids playing. We used to keep the doors unlocked. Doors would be open at night. You could just walk in.”19 A black man rose from a pretty decent neighborhood to run for President but settle for a cabinet position as secretary of Housing and Urban Development. He worried that if public housing were made too comfortable it wouldn’t inspire its residents to claw their way out of there, so he took $31,000 of the taxpayer money that could have gone to improve public housing and spent it instead on a dining-room set for his own office.20

Wasn’t this the American Dream? Ben Carson had beaten the odds to become a renowned pediatric surgeon, an inspiration to millions. He didn’t need to pretend he’d grown up in a worse house than he actually did. He didn’t need to claim to have overcome a “pathological temper”21 that caused him to attack and stab his classmates in incidents CNN was unable to verify. Ice-T suggested Vanilla Ice didn’t have to lie either: “One of his mistakes was he came into the rap business saying he was from the street. He didn’t have to say that. All he had to do was say hey, I’m a white kid, I’m trying to rap, and I want to be accepted. You don’t have to lie and say you’re from someplace you’re not, you know?”22 We had become obsessed with whether or not our public figures were telling the truth—and rightly so—but our fact-checking distracted us from the bigger problems with our impulse to buy into such stories. Being born poor made for a good story, once you got rich. Growing up poor was worth so much that our rappers and politicians were willing to lie about it, yet all it did for most people was keep them poor for the rest of their lives.