Читать книгу A Guest in the House of Hip-Hop - Mickey Hess - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

WHAT SHOULD A WHITE ALLY DO?

Don’t start with this book. Or at least don’t stop with it. Read Ijeoma Oluo, Claudia Rankine, Reni Eddo-Lodge, Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, Patrisse Khan-Cullors and asha bandele, Michelle Alexander, Carol Anderson, Morgan Jerkins, Brittney Cooper, M.K. Asante, Ibram X. Kendi, Jeffrey O.G. Ogbar, Harry Allen, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Michael Eric Dyson, and other black writers at the heart of a renewed and much-needed conversation about race and racism in the United States. You certainly don’t want the only book you read about race to have been written by a white author like me. Nobody’s exactly clamoring to read what a middle-aged white guy has to say about hip-hop, but at the same time I see white authors too comfortable leaving the work of discussing race and racism to authors of color, which both overburdens their writing and reinforces the concept of race as a topic white people aren’t asked to think much about. My perspective certainly shouldn’t replace that of a black writer, but it may provide a point of entry to show the power of black voices on the developing mind of a white kid whose environment encouraged him not to listen. Too often white writers focus on showing they know the right things to say when it comes to race without addressing how they learned in the first place and how they worked to overcome the mistakes they made along the way. That’s the story I’ll try to tell here.

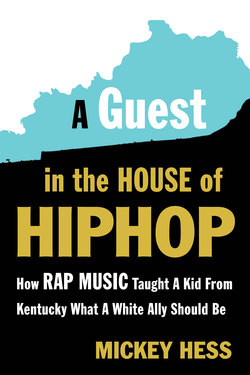

This is a book about how a white man born into racial isolation in small-town America grew up to study and teach the black culture of hip-hop. Born just outside of Science Hill, Kentucky, I grew up listening to the militant rap of Public Enemy while living in a place where the state song still included the word “darkies.” If it weren’t for hip-hop music and my mother’s belief in higher education, I could have slipped into a lifetime of closed-mindedness and casual racism. Growing up in rural Kentucky in the Eighties and Nineties, I had no black teachers, few black classmates, and no black members of my church congregation. This racial isolation fostered a smug certainty about our way of life and a fear that it was threatened by the mere suggestion that there were other ways.

I saw a knee-jerk reaction to the 1990s iterations of multiculturalism and political correctness. When I left home for college in Louisville—the big city to me—my neighbors, coaches, and teachers warned me not to let my professors brainwash me. This was the mentality with which I embarked upon higher education. What were my neighbors clinging to? What were they afraid I might learn? Education is not indoctrination. It’s no mystery why learning about black history tends to make white people less liable to buy into racist thinking and more likely to question the reasons whites invented and embraced those racist notions. It’s no coincidence that the more history I learned, the less I could buy that there was a conspiracy against whites—as my neighbors had suggested—and the more I’ve come to understand the longstanding national conspiracy to keep black people out of white schools, pools, and neighborhoods, as well as the advantages that conspiracy continues to give a white man in 2018.

Listening to hip-hop made me have to think about what it means to be white, while the environment in my hometown encouraged me to avoid or even mock such self-examination. I listened to so much hiphop, and read so many books about it, that when I went on to graduate school it was a natural choice of topic for my doctoral dissertation. Yet the more I studied hip-hop the more I came to look like part of the problem. I was another white professor teaching a black subject, landing a job that could have gone to a black scholar. My dissertation and the book it spawned got me a job teaching Hip-Hop and American Culture at one of the hundreds of US universities that offer plenty of hip-hop courses but employ embarrassingly low numbers of black professors. Schemes like this one make Americans mistrust white people who participate deeply in black culture, yet backing away from black culture entirely is too easy a solution. As a white professor with a longstanding commitment to teaching hip-hop music and culture, I maintain that white people have a responsibility to educate themselves by listening to black voices and then teach other whites to face the ways they benefit from racial injustices, even as I inevitably continue to benefit from them myself. As a white hip-hop scholar I can never allow myself to get too comfortable or too familiar, because writing about white people’s fraught relationship with hip-hop might be my most important contribution.

I have not written a self-help book, but since my subtitle mentions what a white ally should be, I should address from the outset what a white ally should do. It’s a sad fact that many white Americans put more stock in a white voice than a black one, so a conversation between whites offers me an opportunity to speak to America’s history of race relations and introduce the ideas of black thinkers. Such conversations, in my experience, provide frequent opportunities to broach the subject, because white people, when alone, tend to speak their minds on race in a way they’re afraid to do in front of people of color. The thinking goes that they won’t be rebuked because they’re among likeminded friends, and unfortunately, staying silent (as I’ve done too many times in my life) confirms my approval, or at least my acceptance, of hateful or ignorant thinking. In such conversations, I don’t intend to substitute my voice for black voices, but to use the familiarity of my whiteness as a way to introduce the ideas of black thinkers to whites who’ve had too easy a time avoiding them.

Of course, racism is a more systemic problem than the ingrained prejudices of an individual white person. It’s no accident that white Americans aren’t asked to study black history much beyond a cursory nod to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr’s “I Have A Dream” speech once every February. Nor is it an accident that around one in four black men will end up in an American prison,1 or that one in four black Kentuckians has been permanently stripped of the right to vote.2 The United States was founded on racial disparity and designed systems to maintain this disparity via our institutions—our courts, police departments, and prisons, our neighborhoods, schools, and voting booths. In a very real sense, America won’t achieve true change until we change these institutions and systems, but don’t forget that our attitudes are a key part of these systems. The more whites buy into racist thinking, the more invested they are in preserving the systems that advantage whites. We’ve changed systems before—from fair housing to school integration to health care—but then seen the new laws barely enforced and chipped away at and reversed. For legislative change to last, we need to change the way people think.

As a professor, I can have the most influence within the institution of higher education, teaching classes that introduce the history of racial disparity to college students who typically haven’t learned much of it in twelve years of public education. Ideally, those students will become more racially-enlightened citizens who carry their educations forward to do some good in the institutions where they ultimately work. I’ve heard from graduates working as high school teachers and writers and editors. Some, like Robert Lefkowitz, have gone on to rap. J’na Jefferson writes for Vibe. John Gratton has done production work for dozens of hip-hop albums, including Chuck Strangers’s Consumers Park and Joey Badass’s All-Amerikkan Badass. Breanne Needles landed an internship booking shows for the Wu-Tang Clan and went on to work in publishing. Marcus Castro started a clothing line called 2 Familiar, which references an old joke from our hip-hop class. My former students are working as everything from TV cameramen to stand-up comics to cops. We need educated citizens in all those roles. Racism is so ingrained in American culture that it touches every aspect of our lives, so what should a white person do?

Listen to black voices. Study black history. “Education is the apology,” wrote Boston Globe columnist Derrick Z. Jackson in 1997. “White folks need to study slavery to see that they are in the same trap as the 1800s” when “elite white industrialists raked in the profits [while] shafted white workers were left with the consolation that they were still better than black folks.”3 Seek out black voices and you’ll find one introduces the next. I started with hip-hop, but I didn’t stop there. I first heard the names Huey P. Newton and H. Rap Brown in a Public Enemy song. I first heard of Steve Biko and Soul on Ice from A Tribe Called Quest. I heard the Oakland, California rapper Paris mention Frantz Fanon before I saw my college professors assign his writing. I turned up my headphones and headed for the library. But education that isn’t shared only benefits one learner, so make every effort to share your education with others.

Don’t expect black people to take it upon themselves to educate you. Don’t look to black people to reassure you your statements are inoffensive. Don’t assume that you haven’t said anything offensive just because a black person has not called you out.

Don’t assume your black friends or colleagues want to talk about your studies or your journey toward racial enlightenment, but do reach out to ask how they’re doing when a white nationalist march makes headlines, because, as my friend and colleague Sheena Howard once said, “This shit is traumatic.” Don’t say you can’t believe this is happening in this day and age, because your black friends very likely can.

Speak for yourself. Don’t present yourself as an expert on black thinking, but introduce your white friends and colleagues to the words of black thinkers. “Too long have others spoke for us,”4 wrote John B. Russworm and Samuel E. Cornish in the first issue of Freedom’s Journal in 1827. Nearly 200 years later, the book publishing industry remains nearly entirely white, and black professors make up only around 6% of the full-time university faculty nationwide. Russworm and Cornish saw the danger of such a lack of self-representation: “though there are many in society who exercise toward us benevolent feelings; still (with sorrow we confess it) there are others who make it their business to enlarge upon the least trifle, which tends to discredit any person of color; and pronounce anathema and denounce our whole body for the conduct of this guilty one … Our vices and our degradation are ever arrayed against us, but our virtues are passed unnoticed.”5

That problem hasn’t changed enough since 1827. Even with hip-hop’s cultural dominance, the control over what aspects of black lives get presented in the music can be traced back too often to white record executives.

Don’t get too familiar. Don’t believe that your track record of study or sensitivity allows you to make statements that might be considered racist if they came out of the mouth of a stranger. Don’t make having read books by black authors the new “some of my best friends are black.”

Don’t let having aligned yourself with black causes convince you that you’re better than other whites. Don’t congratulate yourself for being conscious, woke, or informed, or having worked uniquely hard to achieve racial enlightenment. If you’ve had educational opportunities denied to other whites, find ways to share what you’ve learned while remembering to acknowledge your own advantages, even down to the all-important factor of having been born to parents who encouraged, rather than discouraged, your learning. Don’t develop a white savior complex but this go-round the uncivilized natives are other whites. J. D. Vance in Hillbilly Elegy criticized poor whites in Kentucky for buying “giant TVs and iPads” rather than saving money, working hard, and pulling themselves out of poverty.6 White Americans have made that same argument for years about black Americans. It was wrong in that cross-racial context and it’s wrong when it’s whites speaking about whites.

Admit your own complicity and work to correct it, but don’t make a show of wallowing in white guilt. Don’t apologize on behalf of generations of racist whites by way of distinguishing yourself from the past or the white masses. Don’t cling to white pride by defending yourself (i.e., listing your antiracist credentials) or defending the white race (i.e., crying Not ALL Whites).

Don’t get defensive. When an eighteen-year-old student asks me why he should have to come to college and be made to feel bad for being white, there’s some power in my being able to admit I used to feel that same way—that I grew up encouraged to reject any talk of the advantages of white skin as an attack against white people. My goal is not to make him feel bad about being white so much as it is to make him think about what it means to be white in context of the history of this country. Since he’s concerned about feelings, I’ll have him read W.E.B. Du Bois’ The Souls of Black Folk, which asks, “How does it feel to be a problem?” or Moustafa Bayoumi, who borrowed Du Bois’s question for its title of his 2009 book How Does it Feel to be a Problem? Being Young and Arab in America. I’ll have him read the words of Mamie Till-Mobley, whose fourteen-year-old son Emmett Till was brutally murdered after he was accused of having whistled in the direction of a white woman. If this student is still stuck on the idea that the real injustice here is the assault on his feelings, he needs to keep reading.

Don’t expect to be congratulated. I stood at a New Jersey protest and vigil in the wake of the white nationalist march on Charlottesville, Virginia. One of the protest organizers—a white woman—kept encouraging cars at the intersection to honk their horns in solidarity with our cause. When a black motorist chose not to participate, the organizer, smiling, shouted, “Come on and join in! We’re doing this for you!” Don’t expect people of color to join in, or even acknowledge, whatever efforts you’re making. Anticipate that people of all colors might be puzzled and even put off by your efforts.

How could someone so committed to organizing protests say something so ignorant? My guess is that she got so swept up in protesting that she was temporarily blinded by self-righteousness. She got so swept up in her conviction that she was being a good person that for a moment she forgot how to be one. It wouldn’t be the first time I’ve seen it happen. I saw countless protestors step over a disabled veteran asleep by his cardboard sign as we marched to Philadelphia’s City Hall for a health care repeal die-in. Perfectly healthy citizens planned to play dead to put on a show for our senators, while this man was actually dying on the street.

Confront hate, but correct ignorance. Boycott corporations. Demand resignations from the CEOs and celebrities. But approach private conversations less with the intent of winning an argument than winning a listener. The racism expressed in everyday interactions has a particular insidiousness that can make black Americans worry that they’re being too paranoid or too over-sensitive or too stereotypically angry or that they can’t help viewing the present moment in the context of so many centuries of bad history. Claudia Rankine’s Citizen shows the poet finds it easier and more fulfilling to confront outright hate (a white man referring to a group of black teenagers as “niggers,” in front of Rankine, a black woman),7 than an insidious comment from a white professor interviewing her for a job (“his dean is making him hire a person of color when there are so many great writers out there”8) or a friend complaining that her son lost his legacy-secured spot in the incoming class at a prestigious university (“because of affirmative action or minority something—she is not sure what they are calling it these days and weren’t they supposed to get rid of it?”9). It may be easier and more fulfilling to confront outright racist aggression, but the most aggressive racists are also the ones least likely to be persuaded to consider your point of view. Facing covert racism, Rankine finds herself caught between biting her tongue versus reinforcing the stereotype of being too sensitive, too aggressive, too quick to play the race card. It would take a tremendous amount of poise and restraint for her to take it upon herself to educate her aggressors, to see each daily slight or microaggression as an opportunity to serve as a patient instructor. I won’t recommend black Americans remain patient in the face of ignorance. After all, it’s been more than fifty years since Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. wrote that he could no longer wait. Why should this work of patiently educating white Americans fall squarely in the laps of black Americans?

White allies can do their best work when they find opportunities to take on the work of patient education. The vast majority of white Americans have the luxury of never having to think much about race, but they sure like to talk about it. We may be unsure if offhand racist comments are rooted more in lack of education than outright hate, or if the intimacy of a one-on-one conversation between whites simply allows for a passive-aggressive masking of hateful attitudes with the excuse of having innocently misspoken. But we cannot make the mistake of using someone’s positive qualities (she’s a protest organizer, he volunteers every Thanksgiving at a homeless shelter) as a way to convince ourselves that such a good person couldn’t possibly mean the racist things he says. Instead, see his potential: he could be an even better person if he studied more history and listened to more black voices and learned how misguided his thinking is. I don’t mean to spare white feelings so much as keep a white friend or colleague from closing her ears to the message, but my strategic patience must not be mistaken for coddling ignorance or acknowledging ignorance as a position as valid as any other.

As a white ally, I can do my best work by heeding the calls for patience and politeness that it would be ridiculous to ask back folks to heed. Without letting racists off the hook or even taking it easy on them, white allies can strategically take on the burden of the restraint that America has for far too long encouraged from black activists. From Martin Luther King Jr’s “This ‘Wait’ has almost always meant ‘Never’”10 to the notion that Black Lives Matter should be more polite, critics have tended to see a particular rudeness in the calls for white Americans to stop killing black Americans. An ostensible commitment to politeness underlies the calls for us to listen to each other, but I don’t buy into the idea that we should give racists a platform so that they can explain where they’re coming from. Racist thinking is rooted in ignorance, and what good is understanding where someone is coming from if it’s a place of ignorance? “Whites, if must frankly be said,” wrote Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, “are not putting in a similar mass effort to reeducate themselves out of their racial ignorance. It is an aspect of their sense of superiority that the white people of America believe they have so little to learn.”11 Too often that white sense of superiority feels assaulted by the suggestion that talking about the lives of black Americans does not require that we give white voices equal time.

That sense of superiority often leads whites to want to dictate not only who gets to talk but how the conversation should sound. Many whites support black causes so long as the activism doesn’t make white people uncomfortable. After Black Lives Matter activists in Seattle snatched the mic at a Bernie Sanders fundraiser in 2015, Ijeoma Oluo wrote, “The reaction to these protesters shed light on the hidden Seattle that most black people know well—the Seattle that prefers politeness to true progress, the Seattle that is more offended by raised voices than by systemic oppression, the Seattle that prioritizes the comfort of middle-class white liberals over justice for people of color.”12 Just months later, the issue of politeness was raised again when Bill Clinton shouted at and admonished BLM protestors in Philadelphia. (The protestors didn’t like the 1994 crime bill that President Clinton signed into law, worsening the mass incarceration of black Americans, and they didn’t like Hillary Clinton’s having referred to youth offenders as “superpredators” in 1996.) Lincoln Blades found Clinton’s exasperation refreshing. “Often,” he wrote in Rolling Stone, “liberals are so well-versed on the polite conventions of respectable and appropriate speech that they can become talking-point robots rather than individuals who have their own set of beliefs … There’s nothing scarier for a minority than not really knowing what the person across from them actually thinks about their intrinsic worth and their fight against oppression.”13

Both writers above point to a particular self-satisfaction on the part of whites who consider themselves forward-thinking or liberal-minded. This self-satisfaction is also wielded against other whites via the schism in class and social standing that makes it easy for educated white liberals to become comfortable in their superiority to the unwashed masses of whites whom they blame for everything from segregation to the election of Donald Trump. If my ambition is to spread knowledge, I cannot approach education by looking down on those I intend to teach. It’s not enough for the most educated of whites to look down on the ones more dedicated to common sense and religion and anti-intellectualism. Attacking the white folks who sit around spewing offhand racism just makes them dig in their heels and take comfort in the old misguided notions of reverse racism and the liberal elite out to get them.

As a professor, I’m undeniably a part of this perceived elite. I won’t deny that I’m fortunate to have a sphere of influence as meaningful as the college classroom, where I, in professor mode, can exhibit a patience I don’t feel in the fight-or-flight reaction that kicks in in my everyday confrontations with my neighbors and cousins. When that student asked why he should have to come to college and be made to feel bad about being white, I didn’t feel myself freeze up and write him off as a lost cause the way I probably would have done with someone so sure of himself in a one-on-one conversation outside my classroom. After all, this student and I were trapped together, like it or not, for the duration of the semester, so I might as well make every effort I can to shake him out of his certainty that reading books by black American authors about black American issues is an affront to his security as a white American. As I said, I could see myself in that student. I could see me, an eighteen-year-old freshman, much quieter and less confrontational but still feeling that I was being somehow punished for my backwoods ignorance when my professors required me to attend a poetry reading by black feminists rather than wait in line at the record store to buy Snoop Dogg’s debut album Doggystyle. I can’t deny that my small-town Kentucky neighbors got into my head when they warned me my professors would brainwash me. I could see myself at eighteen when I looked at my student, but I could also see those screaming white faces from Charlottesville, those marching white nationalists with their tiki torches. Too much patience on my part risks losing him to the hate groups, but too much impatience risks pushing him right into their ranks. My best strategy is to admit I once straddled the same fence he’s straddling, and tell him the story of how I ended up on the right side.