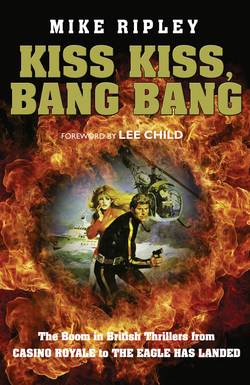

Читать книгу Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang: The Boom in British Thrillers from Casino Royale to The Eagle Has Landed - Mike Ripley, Mike Ripley - Страница 16

1960s

ОглавлениеThe Old Masters, Greene and Ambler, had been proving that ‘abroad’ equalled mystery, suspense, and intrigue for years and were continuing to do so.

Graham Greene’s The Quiet American (Indo-China) in 1955, Our Man in Havana in 1958, and The Comedians (set in Haiti) in 1966 are among his most famous novels. Eric Ambler, who had made his name with serpentine tales often set in old Byzantium, returned to the exotic eastern Mediterranean with The Light of Day in 1962 (filmed as Topkapi) and then tackled Africa in Dirty Story in 1967.

Our Man in Havana, Heinemann, 1958

The Dark Crusader, Fontana, 1963

One group who could travel more than most were journalists. There was certainly a tradition of having a journalist as a sleuthing hero in detective fiction, back to the days of E. C. Bentley, Philip MacDonald and Anthony Berkeley. Some of them, certainly, were rather dodgy characters though as Eric Ambler had warned his readers: ‘The transition from newspaper man to desperado is a more arduous process than some people would have you believe.’3

Hammond Innes – originally a journalist – was generally accepted to be the master of the ‘going foreign’ adventure thriller and he extended his research trips to include settings in south-east Asia, Greece, Malta, and Australia. Not far behind was another veteran, Victor Canning, and although Canning tended to limit his adventures to Europe and the Mediterranean in the Sixties he always preferred to set dangerous adventures involving Englishmen, in foreign locations because ‘in this country you could always call a policeman’.4

The big beast of the thriller pack, Alistair MacLean, certainly varied his settings, though the geographical location of his plots was always somehow secondary to the travails of the hero. In one of his lesser known works, The Dark Crusader, first published in 1961 under the pen-name Ian Stuart, British secret agent John Benthall, posing as a rocket scientist, ends up on a Polynesian island which at first glance could be the home of Dr No or Dr Moreau, possibly both. The reader, however, is not invited (or given the time) to dwell on the exotic setting other than to be reassured that the food served there by a Chinese cook ‘was none of this nonsense of birds’ nests and sharks’ fins’, as the more important concerns by far are: what’s going on, who can Benthall trust and how does he get past the armed guards and those Dobermann-Pinscher attack dogs which weigh between eighty and ninety pounds, have ‘fangs like steel hooks’ and which come at him out of the dark on a moonless night? That’s the sort of local colour the MacLean reader was after.

The undisputed heir to Hammond Innes, when it came to providing foreign locales and being a similarly enthusiastic traveller, was Desmond Bagley, whose novels from 1965 onwards were framed by carefully and often lovingly described scenery from the High Andes to British Columbia, and Sweden to New Zealand.

As was often said about Bagley, his books were not so much about spies or even crimes – though they certainly feature – but about a group of interesting people in an interesting, often dangerous, landscape. In the 1982 Whodunit? Guide to Crime, Suspense and Spy Fiction one of the editors (most likely Harry Keating) wrote Bagley’s entry in the ‘Consumer’s Guide’ section:

[Bagley] derives a good deal of his creative force from the choice of exotic settings, carefully visited in advance. These have ranged from Iceland (Running Blind) to the Sahara (Flyaway), from northernmost Scotland (The Enemy) to southern New Zealand (The Snow Tiger). But he never allows his research, however massive, to get in the way of his story, although what facts he does let on to the pages greatly enhance the authenticity and interest of those stories.

Bagley’s very natural, almost conversational, style convincingly imparts a local flavour without lecturing to his readers, as in Flyaway (1978) when he gives tips on riding a camel as his protagonists are about to cross the desert in Chad:

A camel, I found, is not steered from the mouth like a horse. Once in the saddle, the Tuareg saddle with its armchair back and high cross-shaped pommel, you put your bare feet on the animal’s neck and guide it by rubbing one side or the other. Being on a camel when it rises to its feet is the nearest thing to being in an earthquake and quite alarming until one gets used to it.

In those far-off days before the Internet, Google Earth or Lonely Planet Guides, this was useful information to the sitting-room traveller and had the feel of being written by someone who had been there and done that – as Bagley had. In many ways he could be credited with (or blamed for) being a forerunner of the tsunami of ‘Nordic Noir’ crime novels which was to flood Europe at the end of the century, when he used settings in Norway, Sweden, Finland, and particularly Iceland in his Cold War thriller Running Blind in 1970.

Bagley and his wife Joan spent a month researching in Iceland in 1969 and their visit was clearly a big news event locally as all the Icelandic media reported a press conference they gave towards the end of their stay. When asked the inevitable question ‘why Iceland?’ Bagley, very honestly, replied: ‘Iceland is a very unusual country. It is also helpful, because so few people live here, so should I write some nonsense, then nobody knows what is right except in Iceland.’ A little more seriously, he said, ‘I choose my setting depending on whether people know a little or a lot about the country,’ and acknowledged that in Britain, the popular awareness of Iceland was limited to newspaper headlines about fishing disputes and ‘Cod Wars’.5

Long Run South, Panther, 1965

Snake Water, Panther, 1971

Running Blind, which was filmed by the BBC, was another bestseller for Bagley and in an article in The Writer in May 1973, he said: ‘The plot that was worked out in Running Blind came directly from the terrain and peculiar institutions of Iceland and I do not think that specific plot could have been set in any other country.’

Certainly the television adaptation was well-received and the week after it was shown in 1979, The Observer newspaper ran an advertisement for an ‘Icelandic Safari among the glaciers, hot springs, and volcanoes’ – holiday with the adventurous imprimatur ‘In the trace of Desmond Bagley’.

Yet Bagley was not the first British thriller writer to discover Iceland. Journalist and foreign correspondent Alan Williams had used it as the setting for a key section of The Brotherhood (later retitled The Purity League) in 1968, where the hero, (a cynical, fairly right-wing journalist), flees for his life from the puritanical and very right-wing Brotherhood across an Icelandic glacier, before moving to the final shoot-out climax in communist Poland.

From the start of his career as a thriller writer, Alan Williams had offered exciting foreign locations, recalled from first-hand experience as a foreign, or often war, correspondent. His first novel, Long Run South (1962), was set in Morocco and quickly followed by the excellent Barbouze, which begins among ancient Greek monasteries and meals of bread, olives, dried fish, ouzo, arak, and retzina, all of which (including bread other than white sliced) being rare and exotic things in most of Britain in 1963. Barbouze then becomes both more exotic and also politically topical by switching the action to Algiers, slap-bang – literally – in the middle of civil strife caused by the de-colonisation of Algeria by France.

In his third novel, Snake Water (1965)6, Williams pulled out all the stops when it came to impressing the armchair explorer, setting his treasure-hunt thriller in a rather vaguely located South American country blessed not only with a corrupt ‘banana republic’ government but a topography which included volcanoes, mountains, deserts, swamps, and jungle, not to mention a tribe of native Indians with a ferocious reputation. The plot concerns an ill-assorted quartet of two innocents and two natural-born killers following a treasure map to a hidden cache of diamonds, first across a desert called The Devil’s Spoon:

They woke with the sun hanging like a fireball in the corner of the sky. The glare had gone and they could now see the great hollow of The Devil’s Spoon below. From here it looked less like a spoon than a frying-pan full of steam. The rim ran the length of the horizon in a dark line that was the cliff called the Chinluca Wall. The sky above was the colour of asphalt; below there was not a single land-mark – not a drop of water or blade of grass or cacti or weed or insect; not the smallest thing.

Having crossed this heartless terrain, our intrepid travellers then have to face the hostile wildlife. Blocking their path through the mountains is a phenomenon which any natural history presenter, Sir David Attenborough included, would give their eye-teeth for: the mating dance of highly poisonous snakes seen by the light of a full moon:

Less than ten feet along the ledge were about a dozen snakes. They were thin and long, striped yellow, black and green, twisting and looping with astonishing speed, their scales making a soft rustling sound on the scree. About half of them were moving flat on the ledge in rapid figure-of-eight patterns, the others crawling in and out of holes in the rock, streaking upwards, their diamond heads flashing like the points of spears, then plunging back into the sand to reappear a few feet away, always in the perfect arabesque movements of a meticulous ritual.

This being a red-blooded thriller and not a nature programme, however, the scene does not end well for one of the treasure hunters – nor for the snakes ‘dancing’ in the moonlight. Yet more dangers lurk in ambush for the ragged bunch of adventurers along the way, this time as they enter insect- and leech-infested swamp country.

Then, under the mangroves about thirty feet away, he saw a movement. At first he thought it was a trick of the shadows: a broad undulating mass of copper-red helmets, each the size of a soup-plate, moving slowly towards them like a battalion of surrealist troops without heads or bodies. There must have been more than fifty of them, stretching back under the trees, creeping round the roots in several streams; and along the front ranks, where the faces should have been, there were hundreds of thin white legs like macaroni, treading the mud in a steady rhythmic motion … Ryderbeit studied them for a moment, then frowned. ‘We’d better get out o’here. Swamp crabs – can paralyse you in a few seconds’.

As Ryderbeit is a leathery, not-to-be-trusted, hard-nosed character (and one of Williams’ finest creations), the South American wildlife, once again, does not come off well.

South America proved a happy hunting ground for several thriller writers, just as Africa had for Rider Haggard and Edgar Wallace, and previous generations of adventure-seekers. With its jungles, high mountains, lost cities, and, indeed, lost civilisations, as well as extremely exotic (and dangerous) local inhabitants – piranhas, anacondas, native Indians with blowpipes and curare-tipped darts, not to mention ex-Nazis – it is rather surprising that it was not the setting for more tales of high adventure.

In the same year that Snake Water was published, however, Desmond Bagley produced another top-notch one in High Citadel, a rip-roaring thriller set in the High Andes where the survivors of a plane crash not only have to contend with the inhospitable terrain, but are pursued by an army of rebel soldiers. Fortunately, among the ranks of the survivors are a couple of medieval historians who are able to construct medieval weapons to fight off their attackers.7

Then John Blackburn – who specialised in exotic, sometimes downright Gothic, scenarios – in The Young Man from Lima (1968) had his ageing spymaster hero General Charles Kirk endure a Heart of Darkness journey up a jungle river to a ghost town guarded by an army of very protective soldier ants. In the same year, the veteran Geoffrey Household produced a spooky slice of the picaresque in Dance of the Dwarfs, featuring a lone hero (as usual) manning an experimental agricultural station on the edge of the Colombian jungle. One of Household’s strangest offerings (the first-person narrator is dead before the book starts and the ‘dwarfs’ of the title are not human) the novel is ripe with the author’s obvious closeness to the landscape and the local population, whether human or animal, which is hardly surprising given that Household knew South America from his pre-war days as an importer of bananas into Europe, and then as a travelling salesman selling printer’s inks there, before turning to fiction.

Running Blind, The Companion Book Club, 1971

High Citadel, Fontana, 1967

A less frenetic use of South American settings can be seen in the series of thrillers featuring Peter Craig, a special agent of the Diplomatic Service, which began in 1969 with Twenty-fourth Level by Kenneth Benton. A retired diplomat, Benton had served in the Diplomatic Corps for some 30 years (in fact he was an MI6 officer), including postings to Brazil and Peru, and his hero, Peter Craig (not to be confused with James Munro’s John Craig, a much rougher beast) is a specialist overseas police advisor on security matters who follows in the footsteps of his creator’s diplomatic postings. Craig is, in essence, a consultant who lectures foreign police forces on counter-insurgency strategies and anti-terrorism, often finding he has to leave the lecture theatre and take to the battlefield to prove that the sword is mightier than the whiteboard marker. After his Brazilian baptism of fire, Craig’s assignments took him to Europe and then back to South America, to the High Andes in Peru in Craig and the Jaguar in 1973, which reads in part like a textbook on agricultural economics. The detailed topography may be absolutely accurate, but the reason Peter Craig (and Kenneth Benton) did not become better-known was because Craig was simply not exciting enough a character. There was little, if any, mystery about him and he was rather staid, calmly smoking his pipe while machine guns rattled all around him. You got the feeling that if he wore a jacket with leather elbow patches he would easily be mistaken for a geography teacher.

No such mistake would be made over the adventurers in the distinctly harsh environments provided by South African author Geoffrey Jenkins. His heroes are usually grizzled sea-dogs with wartime experiences they would rather forget, even if the reader is anxious to know more (although in one case the central character is a research scientist dedicated to electrocuting sharks after losing his legs in a shark attack).8 However fanciful his plots, Jenkins was the master of his Southern Hemisphere locations, especially the ‘Skeleton Coast’ and the notorious Namib, ‘the desert of diamonds and death’ in south-west Africa, the Mozambique Channel and the Indian Ocean, the South Atlantic and Antarctica. In A Grue of Ice in 1962, he also set a thriller in the world of commercial whaling (although the nub of the plot is the hunt for something much more rare and more valuable than whale meat), possibly the first, and perhaps the last, thriller writer to do so after Hammond Innes in those Greenpeace-free days.9

Those early Jenkins novels were ‘Adventures’ with a capital ‘A’, the characters being explorers into strange and dangerous environments rather than soldiers or secret agents on a mission. Jenkins spiced his stories with the latest scientific discoveries as well as traditional explorer’s folklore as it surrounded the bizarre landscapes (and seascapes) he described. It was perfectly possible in a Jenkins novel to find the wreck of a top secret Nazi U-boat, a fifteenth-century Portuguese sailing ship stranded in the middle of a desert, blind scarab beetles, a mysterious island seen only twice in a hundred years, the meteorological phenomenon of ‘two suns’, strandlopers – rather unpleasant seashore hyenas, very big and very deadly composite jelly fish (imagine a long string of Portuguese man-of-wars joined together to increase their voltage), and, even, in the Indian Ocean, a giant ‘Devil Fish’ – a manta ray large enough to attack a submarine.

His 1964 novel The River of Diamonds had all his trademark ingredients and then some. This updated pirate tale set on the desolate Sperrgebiet coast of modern-day Namibia, centres on an expedition to mine diamonds from the sea-bed where they were deposited by a prehistoric river – or is that merely a cover to find the hidden treasure, diamonds again, of Heinrich Göring (Hermann’s father) the colonial governor when Namibia was an Imperial German protectorate? As the Daily Telegraph reviewer noted, there are also ‘killer deserts, grizzled prospectors, mass (animal) suicides, savage nomads and a vanished U-boat patrol’ to which could be added some powerful and very deadly natural phenomenon, quicksands, oxygen-less sea, and an attack by Russian torpedo boats. The American magazine Kirkus Reviews called it ‘Good Hollywood’.10

The River of Diamonds, Fontana, 1966

If there had been a prize for the most convoluted journey taken by a hero in an adventure thriller published in 1962, then A Captive in the Land by James Aldridge would surely have been in the running. The story opens with the rather uptight British meteorologist hero Rupert Royce on a flight back from the Canadian Arctic when a crashed Russian plane, with a stranded sole survivor, is spotted on the ice below them. Royce hastily grabs some survival gear and parachutes down to the ice whilst his plane goes off to get help, but then it too crashes, leaving Royce and a badly-injured Russian pilot stranded, 300 miles from the US base at Thule in Greenland. After months of hardship surviving the weather and fighting off polar bears waiting for a rescue that isn’t coming, Royce decides to walk off the ice, grimly dragging the injured Russian with him. Amazingly they survive the gruelling trek and are eventually rescued by Eskimo seal-hunters. Royce returns to England to find himself – embarrassingly – a hero of the Soviet Union and after some rather tedious soul-searching, agrees to accept the offer of Russian hospitality and embarks with his family on a journey to Leningrad, then Moscow, then down to the Crimea where he has expressed a desire to scuba-dive in the Black Sea on the archaeological ruins of the Ancient Greek settlement of Phanagoria.11 With his status as a Soviet Hero and seemingly unlimited access to Russia, Royce has naturally been recruited by British Naval Intelligence to do a bit of spying whilst there, but his heart isn’t in it and in the end he throws away unused his fountain-pen full of invisible ink!

It seemed that James Aldridge, a respected war correspondent in WWII and author of numerous novels, children’s books and non-fiction, started A Captive in the Land as an adventure story. He toyed with the idea of a spy novel, and then almost moved into a man-alone-in-a-foreign-land thriller, but somewhere along the line, in a very long book, lost any sense of making it thrilling. Even the sub-texts of his hero’s Russian love affair and his sympathetic observations of day-to-day Russian life, about which little was known in the West, fail to generate much excitement or suspense and absolutely no tension (the dramatic highlight is when Royce is robbed and his trousers stolen!). You can’t help thinking that an Alistair MacLean hero under the same circumstances would have managed to blow up the Soviet Black Sea Fleet in half the number of pages.

A Captive in the Land, whatever merits it may have had as a ‘straight’ or ‘literary’ novel, failed as a thriller because it simply wasn’t exciting enough and proved that unusual or unfamiliar locations were not in themselves a guarantee of success. To corrupt one of the favourite phrases of reviewers of the day, there was little blood and hardly any thunder (although there is a scene in a lightning storm over the Crimea) and the novel had, in Rupert Royce, a man of extensive private wealth, an unsympathetic, stubbornly unworldly, hero who acts on the pace of the narrative like a sea-anchor.

This was the Sixties and new sorts of hero were needed: confident guys who could survive on their wits in exotic and dangerous foreign environments and who knew about guy stuff, such as guns, aeroplanes and engines. In 1961, there was one such guy waiting, quite literally, in the wings.

I hadn’t been in Athens for at least three months and hadn’t reckoned on being there for another three months, but there I was standing breathing the good fresh petrol fumes of Elliniko Airport and waiting for the starboard engine to get cool enough for me to start an appendectomy on its magneto.

Thus did Gavin Lyall introduce the first of his buccaneering heroes, freelance pilot Jack Clay, in his debut novel The Wrong Side of the Sky and we soon, from Clay’s rather cynical perspective, get a view of the overnight accommodation provided for air cargo personnel in the parts of Athens tourists were probably wise to avoid:

We got a couple of rooms in a small hotel just off Omonia Square … The sheets were patched, the windows gave a good view of the vegetable shop across the street and the doors were the sort that any policeman could knock down with a good sneeze – and probably had. But the place was a lot cleaner than a lot of hotels around there, and it cost us five whole drachmas a night more than the neighbourhood rate.

Here was a hero, British to be sure, but blessed with Raymond Chandler-sharp dialogue, who not only had an interesting way of making a (mostly) legal living, flying cargo planes around the Mediterranean, but who also fitted into the foreign setting with streetwise ease. Here was a first-person narrator who was not lecturing the reader, just telling it as he had experienced it, and so when the hero finds himself in danger – as of course he does – the reader is confident he will get out of that particular scrape by virtue of his wits alone.

In 1964, Lyall repeated his winning formula with an even more suspenseful plot and a setting well off the (then) tourist track: Lapland and northern Finland. The resourceful hero was again a pilot-for-hire, this time called Bill Cary, and at the opening of The Most Dangerous Game he tells the reader:

They were ripping up Rovaniemi airport, as they were almost every airport in Finland that summer, into big piles of rock and sandy soil. It was all part of some grand rebuilding design ready for the day when they had enough tourist traffic to justify putting the jets on to the internal air routes. In the meantime, it was just turning perfectly good airports into sand-pits.

Lyall’s early adventurers may have had military experience and certainly had some special, though not outlandish, skills in that they could drive expertly and could usually pilot an aircraft. They were not masters of disguise, almost certainly not versed in any martial art and relied on gadgets and secret equipment only to the extent that they knew how to use a spanner on a recalcitrant engine. They were the sort of guys other guys wouldn’t mind standing at a bar with, especially if those bars were abroad because Lyall’s heroes fitted in whether in Greece, Finland, France or the Caribbean, and would drink and eat what a regular guy would.

Fictional spies, of course, were on expenses when abroad and usually travelled first class, especially if they belonged to the Bond school of spy-fantasy. They tended to stay in five-star hotels, had limousines and drivers to meet them at the airport, drank the finest alcohol, ate in the finest restaurants – and could not resist giving the reader pointers on the art of foreign travel with style.

The Most Dangerous Game, Pan, 1966

James Bond was the first jet set secret agent – his early appearances in print coinciding with the establishment of commercial jet airline travel – and had seemed happiest when operating abroad. His missions had taken him to America, the Caribbean, Turkey, France, Switzerland and even Japan, with only one of his adventures – Moonraker – being set on home soil. The many candidates to replace Bond in the nation’s affections were just as keen to add to the collection of stamps and visas in their well-worn passports.

One of the leading pretenders to Bond’s throne was the extraordinary Dr Jason Love, who apart from being a country doctor in general practice, was skilled in martial arts and an authority on vintage cars – and he was always willing to help out British Intelligence at a moment’s notice, whenever or wherever needed. Created by James Leasor, Dr Love’s first outing was in Passport to Oblivion in 1964 and the action spread from Tehran and Rome to the wilds of northern Canada.12 Further novels, usually with ‘passport’ in the title offering the prospect of foreign locales, followed with settings from Switzerland to the Himalayas, and the Bahamas to Damascus.

Hot on the heels of Dr Jason Love, 1964 also saw the arrival of Charles Hood, created by James Mayo, who was a clone of James Bond in in his love of the high-life but differed intellectually in that he was a connoisseur of, and dealer in, fine art. With such a day job, or perhaps cover story to maintain, it is of course necessary for Hood to spend quite a bit of time hanging around art galleries in Paris, though he does find time for excursions to the Windward Isles, Nicaragua and Iran in his 1968 adventure Once in a Lifetime, which was re-titled Sergeant Death when it appeared in paperback the following year.

Another 1964 alumnus of the academy of 007 substitutes was ‘barrister by profession, adventurer by choice’ Hugo Baron, created by John Michael Brett, who had a short fictional career working for an organisation known as DIECAST, which believed in violent means to achieve world peace and the elimination of espionage! Hugo Baron was clearly good at his job and duly found himself unemployed after three novels, though not before an adventurous jaunt to Egypt and Kenya in A Plague of Dragons in 1965.

Also making his debut in 1964 was John Craig, a distinctly working-class hero compared to most would-be Bond replacements. Created by James Munro (a pen-name of James Mitchell, who was to go on to invent the more famous David Callan) and appearing first in The Man Who Sold Death, Craig’s early adventures centred on the Mediterranean, the Middle East and Morocco but by The Innocent Bystanders in 1969 he was a paid-up member of the jet-set, zipping between New York, Miami, Turkey, and Cyprus.

Modesty Blaise, one of the few female not-so-secret agents created in the 1960s (or since) already had a cosmopolitan personal background when she first appeared in a newspaper comic strip in 1963 and then a series of novels (and one unlamented feature film) from 1965. Created by Peter O’Donnell, the independently wealthy Ms Blaise not only owns a villa in Tangiers but travels easily through Africa and the Middle East, and in Sabre-Tooth (1966) comes up against an army of terrorists training in Afghanistan in order to ferment revolt in Kuwait – a prescient, though twisted, mirror image of a very modern scenario.

Johnny Fedora, whose career timeline mirrored that of Bond, had already done his fair share of globe-trotting but by the 1960s, author Desmond Cory had settled him into a series of interwoven missions against his KGB nemesis based mostly in Spain.

Without doubt, though, the most popular foreign destination for British spies – though only the reader could be said to be the tourist – was Berlin.

A focal point of diplomatic tension between capitalist West and communist East since the 1940s, the isolated city of Berlin became the espionage hub of the Cold War when the ‘Anti-Fascist Protective Wall’ went up virtually overnight in 1961. A barrier dividing two opposing political systems, complete with armed guards, minefields, and checkpoints in the middle of a city already heavy with history and recent memories of a world war, it was a barrier that could only be crossed in secret ways and on pain of death, or in dramatic rituals of prisoner exchanges or spy ‘swaps’.

Walter Ulbricht, Head of State of East Germany, had created the ideal backdrop and sound stage for spy fiction and four bestselling novels in four years (1963–6) ensured that Berlin would become a film set as familiar to fans of spy stories as Monument Valley had been in the classic westerns of John Ford.

Although the bulk of the action takes place outside Berlin, the key opening and closing scenes of John Le Carré’s The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1963) take place around the Wall.

The tragic hero of the story, Alec Leamas, on his fateful mission into East Germany passes through one of the checkpoints in the Wall, under the watchful eyes of the ‘Vopos’ (Volkspolizei); the Mercedes he is riding in already being followed by a DKW.13 The crossing is suspiciously incident-free.

As they crossed the fifty yards which separated the two checkpoints, Leamas was dimly aware of the new fortifications on the eastern side of the wall – dragon’s teeth, observation towers and double aprons of barbed wire. Things had tightened up.

The Mercedes didn’t stop at the second checkpoint; the booms were already lifted and they drove straight through, the Vopos just watching them through binoculars. The DKW had disappeared, and when Leamas sighted it ten minutes later it was behind them again. They were driving fast now – Leamas had thought they would stop in East Berlin, change cars perhaps, and congratulate one another on a successful operation, but they drove on eastwards through the city.

Getting in to East Berlin might have been easy for Alec Leamas, but leaving it, along with the girl he is rescuing, forms the excruciatingly tense and ultimately doomed finale to the novel. Leamas and Liz, the girl, are forced down the only escape route open to them: going over the Wall in the middle of the night, at a place swept by a searchlight where the guards have orders to shoot on sight. The last briefing from their contact arranging the escape is suitably grim.

‘Drive at thirty kilometres,’ the man said. His voice was taut, frightened. ‘I’ll tell you the way. When we reach the place you must get out and run to the wall. The searchlight will be shining at the point where you must climb. Stand in the beam of the searchlight. When the beam moves away begin to climb. You will have ninety seconds to get over. You go first,’ he said to Leamas; ‘and the girl follows. There are iron rungs in the lower part – after that you must pull yourself up as best you can. You’ll have to sit on the top and pull the girl up. Do you understand?’

‘We understand,’ said Leamas. ‘How long have we got?’

‘If you drive at thirty kilometres we shall be there in about nine minutes. The searchlight will be on the wall at five past one exactly. They can give you ninety seconds. Not more.’

‘What happens after ninety seconds?’ Leamas asked.

‘They can only give you ninety seconds,’ the man repeated.

In The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, John Le Carré was brilliantly describing the bleak topography of Cold War espionage, not a particular city. It was left to Len Deighton to give us the spy’s-eye view as his anonymous hero (‘Harry Palmer’ in the films) arrives for a Funeral in Berlin in 1964.

The parade ground of Europe has always been that vast area of scrub and lonely villages that stretches eastward from the Elbe – some say as far as the Urals. But halfway between the Elbe and the Oder, sitting at attention upon Brandenburg, is Prussia’s major town – Berlin.

From two thousand feet the Soviet Army War Memorial in Treptower Park is the first thing you notice. It’s in the Russian sector. In a space like a dozen football pitches a cast of a Red Army soldier makes the Statue of Liberty look like it’s standing in a hole. Over Marx-Engels Platz the plane banked steeply south towards Tempelhof and the thin veins of water shone in the bright sunshine. The Spree flows through Berlin as a spilt pail of water flows through a building site. The river and its canals are lean and hungry and they slink furtively under roads that do not acknowledge them by even the smallest hump. Nowhere does a grand bridge and a wide flow of water divide the city into two halves. Instead it is bricked-up buildings and sections of breeze block that bisect the city, ending suddenly and unpredictably like the lava flow of a cold-war Pompeii.

If there was ever a need for a tourist audio-guide to coming in to land at Berlin’s Tempelhof Airport (in 1964, that is), then surely Harry Palmer’s is the streetwise voice one would like to hear through the headphones. Over half-way through negotiating a labyrinthine plot of double- and triple-cross, our laid-back and very observant narrator still has time to add flashes of local colour, proving to the reader, thirsty for detail, that Palmer (and Deighton) had been there and seen that.

Funeral in Berlin, Penguin, 1966

The Quiller Memorandum, Fontana, 1967

Oddly enough, Berlin is one of the most relaxed big cities of the world and people were smiling and making ponderous Teutonic jokes about soldiers and weather and bowels and soldiers; for Berlin is the only city still officially living under the martial command of foreign armies and if they can’t make jokes about foreign soldiers no one can. Just ahead of me four English girls were adding up their holiday expenses, and deciding whether the budget would let them have lunch in a restaurant or if it was to be a Bockwurst sausage from a kiosk on the Ku-damm and eat it in the park. Beyond them were two nurses, dressed in a grey conventual uniform which made them look like extras from All Quiet on the Western Front.

Deighton was clearly at home in Berlin and it was to be a happy hunting ground for him – if not his characters – in the following decade.

For Adam Hall’s finely-tuned secret agent Quiller, who made his debut in The Berlin Memorandum (retitled The Quiller Memorandum when the film came out), the city was a very dangerous place, from its wintry streets, smoky bars, and seedy hotels and cafes to its lock-up garages (especially its lock-up garages!). Almost as soon as the super-tough Quiller arrives in Berlin to hunt neo-Nazis, he finds himself being hunted, on foot and by car. At one point he decides to give his pursuers a run for their money indulging, as Quiller himself puts it, in ‘a bit of healthy-schoolboy action’.

Slush was coming on to the windscreen and the wipers knocked it away. We made a straight run through Steglitz and Sudende because I wanted to know if they’d now make any attempt to close up and ram. They didn’t. They just wanted to know where I was going. I’d have to think of somewhere. Their sidelamps were steady in the mirror, a pair of pale fireflies floating along the perspective of the streets. We crossed the Attila-strasse and I made a dive into Ring-strasse going south-east, then braked to bring them right up behind me and make them slow. As soon as they had I whipped through the gears and increased the gap to half a block before swinging sharp left into the Mariendorfdamm and heading north-east towards Tempelhof. Then a series of dives through back streets that got them going in earnest. The speeds were high now and I had the advantage because I could go where I liked, whereas they had to think out my moves before I made them, and couldn’t, because I didn’t know them myself until the last second.

Clearly, in those far-off days before cars had sat navs, Quiller was the man to have behind the wheel when being tailed by the bad guys in Berlin.

It could be a pretty hostile place even if you were a Soviet double-agent trying to escape from the Western half to find sanctuary in the East, a clever inversion of the usual plot-line but exactly the scenario facing the character Alexander Eberlin in Derek Marlowe’s A Dandy in Aspic.

Eberlin got out with the other few tourists and curiosity seekers, and stood on the platform a moment taking stock. The blue-coated railway guards checked the compartments, and glancing up Eberlin could see, framed high on the metal catwalks of the roof, the silhouettes of two Vopos, immobile, machine guns resting on their hips. He had known of an East German youth who had tried to escape by clutching onto the roof of a train, and of another who had hid in the engine of a locomotive. Both had died on the journey. One shot from above, here, the other, untouched, unnoticed by the Vopos, entering the safety of the west as a charred, burnt-out body. But that was of no consequence to Eberlin. His journey was the other way, crossing the Wall as a mere tourist. A simple procedure.

By 1966 when A Dandy in Aspic was published and 1968 when the film came out14 there would have been thousands of British thriller-readers who knew, quite confidently, that Eberlin’s journey would be far from simple. Fans of spy fiction, even those who had never been to Germany, knew all about Vopos, checkpoints, Tempelhof, ‘death strips’ around the Wall and the Ku-damm. They were well aware that everyone reading a newspaper on the street was a spy and every tobacconist’s kiosk was a dead letter drop.

There were many spy films in that peak period around 1966 and there would be many more thrillers set in Berlin both contemporary and historical, in the years to follow, but those four novels in quick succession by Le Carré, Deighton, Hall and Marlowe – all distinctively different in style – firmly established Berlin as the spy capital of the thriller world. Berlin’s reputation as a sort of espionage Camelot, where anything could happen and probably did, lasted until November 1989 when the Cold War began to thaw rapidly by popular demand with hardly a spy or a secret agent in sight.