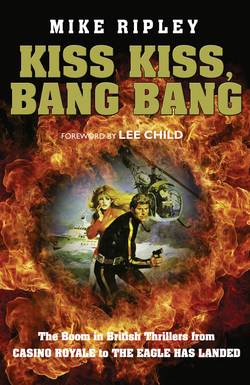

Читать книгу Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang: The Boom in British Thrillers from Casino Royale to The Eagle Has Landed - Mike Ripley, Mike Ripley - Страница 9

PREFACE

ОглавлениеI am of the luckiest generation, the one which avoided National Service and enjoyed a fee-free university education – they even gave you a grant for going.

I spent my early teenage years, and all my pocket money, reading thrillers. It was the first half of the 1960s and I could, by haunting second-hand bookshops and market stalls, usually pick up two, sometimes three, recent paperbacks for the same price as a ‘Top Ten’ 45 rpm vinyl single, which seemed a far better use of my limited disposable income. At least that was my thinking until I discovered girlfriends, and the Rolling Stones recorded Beggar’s Banquet.

I was brought up in a house where a large pile of library books, all fiction, were refreshed every fortnight. Even in a small coal mining village in the West Riding of Yorkshire, there was a public library attached to the infant school which was open two or three evenings a week and allowed four books to be borrowed on each library ticket. My father was a voracious reader of Westerns whilst my mother’s passion was for historical novels. I read thrillers and I knew exactly what I meant when I said that then, although today I would differentiate and describe myself as having started out on adventure thrillers and then moved on to spy thrillers. Unlike many of my peers, science fiction did not entice and detective stories or ‘whodunits’ to me were stale and unappetizing (with the singular exception of Raymond Chandler).

A thriller would offer excitement and almost certainly a connection to WWII. This was a familiar and important reference point as the comic books I had been brought up on as a young lad did not feature Batman, Superman or a Hulk, but soldiers – invariably British or Commonwealth troops – fighting on land, sea, and air against implacable German, inscrutable Japanese and unreliable, if not cowardly, Italian foes. These 64-page book-format magazines were published, rather grandly, as ‘Libraries’. There was War Picture Library, Battle Picture Library, Air Ace Picture Library and, from a rival stable, Commando. They cost a shilling (5p) each and were, as far as I could tell being a bit of a military history buff, pretty accurate when describing the campaigns of World War II.

Why the obsession with WWII? I do not come from a military family, had no career aspirations in that direction (not even the Boy Scouts), and the war itself had ended more than seven years before I was born. Yet it somehow dominated my childhood. The headmaster of my village primary school was a former Royal Navy chief petty officer, the village priest had been a Chaplain with the 14th Army in Burma, I had an impressive collection of toy soldiers, and war films always seemed to be on television – mostly proving that no prison camp could ever hold plucky British escapees when they set their mind to it. When the minor public school I attended took the revolutionary step of starting up a Film Club, the first feature it showed was The Guns of Navarone. (The Headmaster who sanctioned the formation of that Film Club also prohibited any boy from going to the local cinema to see Lindsay Anderson’s If … in 1968. He was clearly a man who understood the power of film.)

It was inevitable that I would discover Alistair MacLean’s wartime classic about the Arctic convoys, HMS Ulysses, and although it is (honestly) more than fifty years since I read it, I can vividly recall incidents from it, not least the scene in a snowstorm when the ship’s pom-pom guns are fired whilst their metal muzzle covers are still in place.

This was a war novel, but it was a tense, dramatic and thrilling story with lashings of suspense and mystery. Not ‘mystery’ as in ‘whodunit?’ but rather ‘how can they survive this?’ The next MacLean I tried, South by Java Head, was also set during WWII but with more skulduggery than actual combat. Other MacLean books were devoured in quick succession and these were not war stories, yet the heroes were resourceful and brave, the stakes life-and-death, the settings ranging exotically from the South Seas to Greenland, and the action fast and furious. These were not only ‘what is really going on?’ mysteries but also ‘how do they get out of this?’ adventures.

I was no longer reading war stories, I was reading thrillers and then, at the age of 12, I discovered James Bond and realised there was more than one type of thriller out there.

With the benefit of half a century of hindsight I realise that there was a real purple patch of British thriller writing in the Sixties and into the Seventies and I had been hungrily reading my way through it. The ‘Golden Age’ of the British detective story (usually accepted to be the Twenties and Thirties) had well and truly lost its lustre by the Swinging Sixties, but a new generation of thriller writers had emerged after the war, appealing to a much wider audience. Thanks to the expansion of public libraries and attractive, mass market paperback editions British writers dominated the national and international bestseller lists. Nobody, it seemed, when it came to action-adventure heroes, secret agents, or spies, did do it better.

After the dull, austere post-war period as Britain declined as a world power, its thriller fiction had – like British pop music and Carnaby Street fashion – moved from black-and-white to Technicolor. The thrillers just kept coming: bigger, brasher, and more fantastical than ever. The early death of Ian Fleming in 1964 did nothing to slow the rush of would-be successors to Bond, in fact it accelerated the flow as did the success of the Bond films. New voices joined in, establishing a school of more realistic spy fiction born in the shadow of the Berlin Wall and more films followed. The year 1966 seemed to have been a peak year, with twenty-two spy or secret agent films released in the UK – admittedly several of them spoofing the genre and only a few of which have stood the test of time.

Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang attempts to be a reader’s history – specifically this reader – of that action-packed period around the Sixties when, having lost an Empire, Britain’s thriller writers and their fictional heroes saved the world and their books sold by the million. It was very much a British initiative and it only faltered in the mid-Seventies when American thriller writers began to flex their muscles, different types of thriller emerged, and the detective or crime story began to enjoy a renaissance.

This book concentrates unashamedly on the British spies, secret agents, and soldiers, and their creators and publishers, who saved the world from Nazis, ex-Nazis, proto-Nazis, the secret police of any (and all) communist country, super-rich and power-mad villains, traitors, dictators, rogue generals, mad scientists, secret societies, ruthless businessmen and even, on one occasion, an ultra-violent animal protection league which kills anyone who kills animals for sport! I will shamelessly ignore the fictional heroes of other countries and concentrate on British authors, with the exception of a handful of Australians and South Africans, whose primary publishers were in the UK.

It will also limit itself to thrillers rather than ‘detective stories’ or ‘whodunits’. This means that some famous names hardly feature at all, those authors who may well have dipped a toe into the thriller pool but are far better known for their crime novels; for example, the wonderful and much-missed Reginald Hill. Similarly, I will down-play one of my favourite writers, that supreme stylist P. M. Hubbard, who wrote novels of suspense on a domestic, almost micro, level. The thriller-writers taking centre-stage here are those who worked on a broader canvas with sweeping brush-strokes and who came to prominence in the period 1953 to 1975. Some who had established themselves before the Second World War were still writing and experienced something of a ‘second wind’ in the Swinging Sixties.

I should insert here a warning: fans of Eric Ambler (1909–98) and Graham Greene (1904–91) will feel themselves short-changed. Both these authors were immensely influential on the form and tone of the thriller genre (novels and films); indeed, their surnames became adjectives frequently used by reviewers. It was high praise indeed for a thriller to be called ‘Ambler-esque’ and everyone knew exactly where ‘Greene-land’ was. Yet neither of these giants were a product of the period under scrutiny as they had cemented their reputations two decades previously, although both were still producing work of high quality, notably Ambler’s Passage of Arms (1959), The Light of Day (1962) – famously filmed as Topkapi, and The Levanter (1972); and Greene’s The Quiet American (1955), Our Man in Havana (1958), and The Comedians 1966). Their legacy and importance in the genre will be acknowledged, though not in enough detail to satisfy their dedicated fans. I have also relegated Leslie Charteris and Dennis Wheatley to the pre-war era for, although ‘The Saint’ was an immensely popular figure on British television in the early Sixties, Charteris had ceased to produce full-length novels and Dennis Wheatley’s novels in the period under scrutiny tended towards the historical or the occult stories with which he had made his name in the Thirties.

One limitation is not self-imposed, and that is the absence of women writers. Adventure thrillers and spy stories tended to be what is known in the book trade as ‘boys’ books’ or, pejoratively, ‘dads’ books’ and were to a very great degree, written by men – some might say men who had never grown out of being boys. A notable exception was Helen MacInnes, a Scot based in America, whose first novel had appeared in 1939. By the Sixties, she was a well-established and popular writer and had three notable bestsellers in that decade, but she, like Ambler and Greene, was not a product of that period when Britain ruled the thriller-writing waves and so gets an honourable, but passing, mention here. And it should not be forgotten that it was in the Sixties that some rather talented female writers, notably P. D. James and Ruth Rendell, were laying the groundwork for a revival in the British detective story and crime novel.

It is difficult to pin-point the exact end of this ‘Golden Age’ (or purple patch) of dominance by British thriller writers. One option would perhaps be the death of Alistair MacLean – the biggest name in the adventure thriller market – in 1987, or alternatively the collapse of the Berlin Wall in 1989, which threatened to put many a spy-fiction writer out of business. In truth, the writing was on the wall (if not the Berlin one) from roughly the mid-Seventies onwards as the Americans, slightly late as usual, entered the fray.

The beginning of the boom is rather easier to identify. The 1950s were grey and austere for a supposedly victorious wartime nation whose empire was starting to crumble. You might say Britain had been expecting you, Mr Bond …