Читать книгу Zen Gardens - Mira Locher - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

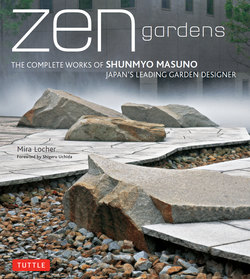

ОглавлениеThree carefully arranged rocks in a bed of raked gravel in the Chōsetsuko courtyard garden at the Ginrinsō Ryōkan condense the essence of the universe into a few simple elements.

TRADITIONAL ZEN GARDENS

IN THE 21st CENTURY

A beautifully shaped pine tree growing on an island of moss is balanced with a rough rock rising from the pond in the garden at the Kyoto Reception Hall.

“In Japanese culture,” writes Shunmyo Masuno, “rather than emphasizing the form of something itself, more importance is placed on the feeling of the invisible things that come with it: restrained elegance, delicate beauty, elegant simplicity and rusticity.”1 The invocation of these qualities is deeply rooted in Japanese aesthetics and is a central tenet in the traditional arts of calligraphy, flower arrangement, tea ceremony, and garden design, among others.

In his gardens, Masuno creates these feelings by emphasizing the design of the atmosphere of a place, rather than the shape of a space or object. Of course, it is possible to achieve this with contemporary materials and compositions as well as long-established elements and arrangements, but in many of his gardens Masuno makes a conscious choice to utilize traditional materials and compositional devices—to create a “traditional” garden. But what is a traditional Japanese garden in the twenty-first century—and what is its role in contemporary life?

First, it is necessary to explore the concept of tradition. A tradition is not understood as such until it is viewed from a perspective outside the culture. Until there is something different with which to compare or contrast a traditional belief or practice, such conventions are not considered “traditional”—they are customary everyday practices, part of a living history developed slowly over time. When an outsider or someone who has experienced a different manner of doing things is able to see the belief or practice in the context of a greater realm, only then it becomes possible to understand it as “tradition.” This is exactly what occurred in Japan during the Meiji period (1868–1912), when, after more than two centuries of self-imposed isolation, Japan opened its ports to trade with the outside world and suddenly had a great influx of Western ideas and goods. Everyday life began to change, and with it the traditional practices were recognized by their dissimilarity to the new ideas entering the country.

Once a practice or belief is identified as traditional, the tradition does not necessarily end. However, the perpetuation of the tradition becomes a conscious, intentional act. The practice or belief may continue unchanged, as a simple copying of what has come before, or it may necessarily entail the continued development of that practice, especially if the essence of that tradition relies on its further development.

A traditional Japanese garden built today falls under that second category, of continued development. Because a traditional Japanese garden is designed to fit a particular context and place, it is illogical—and without doubt some would argue impossible—to replicate a historic garden. The designer must use the proper ingredients and adapt the recipe to the specific conditions of a given site.

Gardens were formed by making use of the natural scenery and geographical features, and adjusting the garden to suit the surrounding environment.... They are designed to merge with the surrounding scenery. When trimming trees in gardens, it is the same: Parts that stand out are trimmed closely and carefully, but parts that are connected with their surroundings are trimmed so they gradually adapt to the surrounding nature.2

While background trees are shaped to blend into their surroundings, prominent trees in Japanese gardens are pruned and trained to bring out their unique characteristics. This close and careful trimming of these trees is an example of “a highly conscious aesthetic of naturalism,” described by garden historian Lorraine Kuck as having developed with the influence of Zen Buddhism from “a simple love of nature.”3 This “highly conscious aesthetic of naturalism” is fundamental to all traditional gardens in Japan, but it is applied differently in each garden depending on the designer’s concept and the elements utilized in the design. For example, in his traditional gardens Shunmyo Masuno utilizes the time-tested elements and materials of this aesthetic—water in waterfalls, streams, and ponds; rocks for dry waterfalls, streams, oceans, and rock groupings; and plants for ground cover, focal-point plantings, and arrangements of flora. Yet each use of these elements is different and distinct, emphasizing the unique character of each garden.

Water drips from a bamboo spout into the carved stone shihō hotoke tsukubai chōzubachi (four-sided Buddha water basin) in the Mushintei garden at the Suifūso Guesthouse.

Historical garden manuals, such as the eleventh-century Sakuteiki (Memoranda on Garden Making), the oldest known treatise on garden design, teach the skill of observing nature to learn how to place rocks in a stream or prune a tree to appear natural. These observations have led to the development of specific elements, such as waterfalls or rock arrangements, which can be adapted to a particular context. For example, in the Kantakeyama Shinen garden at the Samukawa Shrine, Masuno features a waterfall in the dan-ochi (stepped falls) style, while in the garden at the Kyoto Prefectural Reception Hall, he incorporates a nuno-ochi (“cloth veil” falls) waterfall. Each such traditional element is chosen for its particular visual and auditory role within the specific garden. It is Masuno’s design skill that brings together these traditional elements in a unified and balanced composition that imparts an aesthetic of elegance, beauty, simplicity, and rusticity.

In the Keizan Zenji Tembōrin no Niwa at the Gotanōji temple, a gravel stream cuts through moss-covered mounds punctuated with large roughly textured rocks.

With this close connection to the formal elements of historic gardens, the traditional Japanese garden plays a distinct role in contemporary life. Industrialization and human progress have produced an enormous number of new materials and design ideas, yet it is clear from Shunmyo Masuno’s prolific practice that there still is a desire to build new gardens in the traditional style. It must be more than mere nostalgia for the old ways of doing things that inspires clients to request a traditional garden or inspires Masuno to design one. Certainly, in the case of a garden at a Buddhist temple, it is logical to expect a traditional garden if the temple buildings are constructed in a traditional style, such as those at Gionji and Gotanjōji. However, for a private client with a contemporary house, as is the case of the Shojutei and Chōraitei gardens, the style of the garden is not required to mimic the style of the architecture but must complement it. The traditional garden is desired not specifically for its style, but rather for its ability to connect the owners with nature and in doing so provide both a sense of tranquility and an opportunity for deep self-reflection.

This connection to nature and the sense of serenity and self-reflection that accompany it go back to the inherent role of nature in Japanese culture, born out of the conditions of the natural environment in Japan. At the same time, the time-honored elements and symbols of traditional Japanese gardens continue to create the invisible qualities of “restrained elegance, delicate beauty, elegant simplicity and rusticity.”

SŌSEIEN

RETREAT HOUSE KANAGAWA PREFECTURE, 1984

The stone-paved approach to the guesthouse at Sōseien creates the feeling of wandering along a forested mountain path.

Nestled on a hilltop with long views to the surrounding mountains, the garden was named Sōseien by the owners, meaning “refreshing clear scenery.” Serving three different functions, the tripartite garden encircles the guesthouse run by the Tokyo Welfare Pension Fund and leads down the hill as the entry path. First, the entry path sets the mood, giving the visitor a sense of winding through deep mountains. Next the main garden opens out from the lobby and restaurant spaces with a series of low horizontal layers that mimics cloud formations and draws in the nearby mountains. Finally, the garden viewed from the traditional Japanese baths provides a more private, secluded scene of nature highlighted with a swiftly flowing waterfall and a quiet pond.

Flat stones in a random informal (sō), pattern form the surface of the entry path. Large stones commingle with small ones as the path meanders up the gentle slope. Closely trimmed bushes interspersed with multihued trees and a few large rocks are carefully positioned to appear natural and provide changing focal points along the path. Before long, a glimpse of the building emerges among the greenery. While the end of the path is visible, the main garden is not yet revealed, giving a feeling of pleasant anticipation. This sense of a relaxed tension, created during the walk up the path, allows both a physical and a mental transition. While physically moving up the hill, the mind is invited to take in the surrounding nature and release the cares of the day. The sensation of relief combined with expectation increases with each step closer to the guesthouse.

The design principle of shakkei (borrowed scenery) is used to incorporate the distant mountains into the composition of the garden, as viewed from the lobby.

A layer of gravel creates the transition between the guesthouse and the garden and also functions to absorb rainwater dripping off the eaves.

A sequence of entry spaces continues that transition from outside to in and from the activity of daily life to relaxation. Once inside the guesthouse, a right turn into the lobby opens up a vista of the main garden with the mountains beyond. Designed to bring the faraway views of the mountains into the garden—a design principle known as shakkei (borrowed scenery)—the main garden features a grassy lawn interspersed with low, cloud-like layers of closely clipped hedges and a few strategically placed trees and rocks. The low mounds of dense hedges are made up of many different types of plants, primarily yew and azalea, chosen for their varied seasonal colors. At the end of one central mound, a low dark angled rock interrupts the soft flow of the greenery. This abrupt change captures the viewer’s attention, allowing for a more focused awareness of the garden as a whole. A slightly taller row of hedges forms the boundary of the garden, containing the lawn and hedge-clouds and defining the fore-, middle-and background of the view. The long vistas with layers of horizontal space give the sense of being in the sky, floating among the clouds near the mountaintops.

When viewed from the bathing areas, the spaces of the garden constrict, with the trees, rocks, and ground cover reflected in a small pond and the mountains visible between the trees.

The hedges are planted and trimmed to appear monolithic in their cloud-like forms, but they consist of many different types of plants, which give variety in their leaf shapes and colors throughout the seasons.

The site plan of the Sōseien retreat house shows the open areas of the garden relating to the public spaces of the building and the more compact garden spaces near the private areas.

The rough texture and dark color of the rocks in the foreground provide contrast to the gentle slope, curved forms, and muted colors of the hedges and distant mountains.

While the main garden is open, with expansive vistas accented by low mounds of hedges, the garden viewed from the baths allows only momentary glimpses of the mountains beyond. Evergreen and deciduous trees, planted to give privacy while not completely blocking the view, form the background of the compressed spaces of the garden. A stream meanders along rocky banks toward a waterfall, which opens out into a pond in the foreground. The curves of the stream together with the fingers of land create layers of space, giving the garden a feeling of depth and great size. Bushes, ferns, and ground cover are closely planted to reflect the dense vegetation of a lush mountain scene. They vary in scale to support the concept of spatial layering—an important design principle executed differently in each of the three parts of Sōseien.

The layering of space in the Sōseien garden produces a sense of spatial depth that stimulates the viewer’s imagination. “Making people imagine the part they can’t see brings out a new type of beauty.”1 The three varied parts of the Sōseien garden allow the viewer three different ways to exercise the imagination, experience this sense of beauty, and reconnect with nature.

銀鱗荘

GINRINSŌ

COMPANY GUESTHOUSE

HAKONE, KANAGAWA PREFECTURE, 1986

The guesthouse building sits on the north edge of the T-shaped site, with a gravel court on the east side in front of the entry and the main garden stepping uphill from the building on the south side.

Located in the mountain resort area of Hakone, the Ginrinsō garden is designed with the site and the specific visitors in mind. The garden complements a guesthouse for the company from which the garden gets its name—a company that originally made its money from herring fishing. The guest-house, planned for workers who typically go for a relaxing weekend stay, has a design reminiscent of a traditional sukiya-style inn, which spreads across the top (the north side) of the T-shaped site. The garden wraps the perimeter of the site but mostly extends out to the south, along the stem of the T.

The primary views of the main area of the garden are visible from the guest-rooms and the common spaces. Traditional tatami-matted guestrooms offer framed scenes of the expansive lawn leading to a pond, which is backed by a hill featuring a tall two-tiered waterfall. The hill emphasizes the vertical dimension of the garden and also gives the suggestion of something beyond.

The garden path starts from the curved bridge at the edge of the pond near the guesthouse and climbs through the garden to the top of the waterfall for a view back to the guesthouse and the mountains beyond.

Subtle nighttime lighting enhances the colors and forms of the main elements of the garden, creating views different from those seen during the day.

The garden visible from the bathing spaces features a cylindrical stone chōzubachi (water basin) and a single maple tree in front of an arrangement of rocks and shrubs with trees behind.

Sturdy rock retaining walls contain the garden and border the gravel-covered approach and entry court of the Ginrinsō guesthouse.

Carefully composed for balanced views when seen from both the interior of the guesthouse and while walking through it, the garden offers a variety of experiences—both for the eyes and the mind.

Stepping-stones lead from the guesthouse out to the garden, where the visitor can traverse the lawn and then cross the pond on a gently curving bridge. From the pond, a gravel path climbs up and continues behind the hill. It winds through dense masses of clipped azaleas and loops through a heavily wooded section of the garden, reminiscent of a mountain trail. The path continues to the top of the hill—the starting point for the ten-meter-high waterfall, where views unfold back to the guesthouse and the mountains beyond. The path provides varied scenes and moments of discovery, from the quiet solitude of a secluded mountain trail to a moment of pause on the bridge, observing the colorful ornamental carp in the pond and listening to the water splashing off the rocks in the waterfall.

With its tall height and continuous sound, the stepped waterfall is a focal point in the garden and also draws the viewer’s eye into the high depths of the garden.

Tucked into the northwest corner of the site, a smaller garden designed to be viewed from the baths is much more enclosed and private, separated from the main garden by a wall. It features rough rocks set into a hill and interspersed with plants, as well as a stone chōzubachi (wash basin), reached by stepping-stones leading through the pea gravel surface in the foreground. Low mounds, green with ground cover and interposed within the pea gravel, form the base of the rocky hill. A few special trees, chosen for their form and seasonal color, are strategically placed on the hill for visual emphasis and focus.

As visitors generally arrive on a Friday evening and depart on a Sunday, the main area of the Ginrinsō garden incorporates subtle lighting for nighttime viewing. Concealed in hedges and behind rocks, the lighting apparatus is imperceptible during the day. At night, it illuminates specific trees and objects, like the curving bridge and the stone lantern positioned at the edge of the pond between the bridge and the waterfall. The lighting pattern is varied during the two nights of a visitor’s stay, allowing the pleasure of discovering different ways to see and experience the garden.

The gently arched bridge connects the lawn adjacent to the guesthouse to the meandering path, which steps up the hillside through the hedges and into the densely planted trees.

Tiled terraces and long roof eaves extend the interior space of the reception buildings into the garden, while the pond and islands of the garden move under the terraces to bring nature inside.

京都府公館の庭

KYOTO PREFECTURAL

RECEPTION HALL

KYOTO, 1988

The teahouse nestles into a high corner of the garden, with the pond at the opposite lower corner adjacent to the reception hall.

The Kyoto Prefectural Reception Hall is an oasis hidden in the middle of the city of Kyoto. The building houses two main functions: a multi-purpose hall open to the public, which allows only a glimpse into the surprising natural scenery of the garden, and a formal reception room used to entertain dignitaries visiting from abroad, which opens out to the lush welcoming greenery. Designed with layers of spaces ascending a gentle hillside and defined by the varied heights of shrubs and trees, the garden appears much larger than its actual size.

A terrace faced with a grid of stone tiles extends from the reception hall out toward the garden. A gentle expanse of grass and water, bounded on one side by a wing of the L-shaped building and edged with rounded bushes and leaf-filled trees, greets the visitor in a welcoming gesture of openness and abundance. Although the sharp geometry of the terrace contrasts the gentle character of the garden, it has a strong spatial and physical connection to the garden. At one end the pond slips underneath the stone platform, while at the two locations where doors open from the hall onto the terrace, textured stepping-stones break into the gridded stone surface and lead into the garden.

Designed both to be observed from inside the hall and while following the paths that lead through it, the garden offers a variety of multi-sensory experiences. Two primary focal points—a waterfall at one side of the garden and a teahouse at the other—are nestled within the lush trees. The traditional design of the teahouse contrasts the reception hall building, giving foreign visitors a glimpse into Japan’s history. Water cascades over the falls into the stream meandering down the hillside, guided by rough stone borders and edged with azalea bushes and other greenery, providing a soothing backdrop of natural sounds. The paths lead through the layers of the garden, first across the open expanse of the slightly rolling grass-covered lawn and then among the layers of rock and shrub groupings, past the stream and waterfall to the teahouse waiting bench and the teahouse itself. At certain points along the path, the garden is designed for glimpses back to the reception hall, creating a continuous experience of changing yet familiar views.

Glimpses of the teahouse, with its entrance gate set off to one side, are visible across the lawn in the foreground and beyond the hedges and trees in the middle ground of the garden.

The rough textures and varied shapes of the stepping-stones contrast with the grid of the tiled terrace and bring the garden space under the eaves of the reception hall.

The garden slopes down toward the reception spaces with layered hedges and a meandering stream that flows into the pond and under the terraces anchored by islands.

Stepping-stones lead from the gate to the teahouse. Moving carefully from stone to stone emphasizes the transition from the everyday world to the mindset of the tea ceremony.

For nighttime viewing, strategically placed lights illuminate the main elements of the garden, such as the ryūmonbaku (“dragon’s gate waterfall”), in sixteen different scenes.

Both carved from stone, the chōzubachi (water basin) expresses refined symmetry and the Tōrō (lantern) contrasts the precise geometry of a circle within an irregular shape.

The garden of the Kyoto Prefectural Reception Hall is planned with one especially unusual element. As the hall often is used at night, the garden is designed to be viewed both in the daylight and with artificial light. But rather than a static series of spotlights within the garden, a computer-controlled sequence of lighting effects provides a continually changing experience. In a fifteen-minute cycle, soft lights lead the eye to different focal points throughout the garden—emphasizing in turn the waterfall, rock groupings, arrangements of closely clipped azalea bushes, a tōrō (stone lantern) and chōzubachi (wash basin), and the like. The lighting is another device skillfully used to connect the interior space of the formal reception hall with the exterior spaces of the lush, welcoming garden. Through this integration of contemporary technology and traditional techniques, the design of the Kyoto Prefectural Reception Hall garden also reinforces Masuno’s goal of creating spaces that engage the viewer’s imagination and sense of self-awareness.

Carp add color and movement within the pond—another element that expresses the temporal quality of nature within the garden.

ア―トレイクゴルフクラブの庭

ART LAKE GOLF CLUB

NOSE, HYOGO PREFECTURE, 1991

An outdoor bath constructed of smooth granite is set within the raked pea gravel of the enclosed karesansui (dry) garden adjacent to the locker rooms and bathing areas.

The main garden encircles the pond, with the golf course extending beyond it, while the private karesansui (dry) garden wraps the northeast corner of the clubhouse.

Exiting the cavernous clubhouse of the Art Lake Golf Club toward the golf course, the visitor is met with a powerful scene of a large pond with a strong, tall waterfall at the opposite shore. The sight and sound of the water flowing quickly over the rocks into the pond is at once energizing and calming. This balance of contrasts—the Zen principle of creating a single unified whole from seemingly opposing parts—is fundamental to this garden.

The expansive garden is made of two distinct parts. The main garden is focused on water—the waterfall, stream, and pond—with islands of granite planted with black pine trees evoking the scenery of the Japanese Inland Sea. The second garden is a secluded karesansui (dry) garden, which wraps a corner of the clubhouse building, allowing intimate views from the locker rooms and the traditional Japanese baths.

Two primary concepts, both intended to establish a sense of calmness and freedom, drove the overall garden design. First, rather than a direct view from the clubhouse to the golf course, as is typical, the vista should be toward the garden, with the golf course initially our of sight. Here tall “mountains” of earth and stone—artificially constructed in the mostly flat landscape—conceal the golf course behind them. The mountains appear quite natural, but a concrete foundation supports the enormous rocks that define the waterfall and buttress the earth. These rocks, used in their natural state, were excavated when creating the golf course. The second concept stems from an important Zen notion, which in Shunmyo Masuno’s words is present in any “true Zen garden.” The principle is to create “a ‘world free of a sense of imprisonment,’ full of beauty and tranquility, and completely devoid of any sense of tension.”1 This freedom and tranquility allows the viewer to let go of the cares of everyday life and focus on the beauty and enjoyment of being in natural surroundings. Masuno’s ability to create tranquil harmonious compositions with juxtaposed and contrasting elements—a calm pond and a roaring waterfall or a flat bed of pea gravel interrupted by layers of rough rocks—is the result of his long Zen training.

On entering the garden from the clubhouse, the land is flat with a wide path leading in two directions, some low ground cover, and a beach-like crescent of stone at the edge of the pond. The path continues to the left to the tea-room café, with its own small garden nestled within one end of the main garden. A glance in the direction of the café reveals a second, smaller waterfall across the water. The power of the primary waterfall guides the visitor to the right as the path narrows, crosses a wood bridge, and winds through the layers of clipped shrubs and over stepping-stones, following the perimeter of the pond and circling back to the café. Adjacent to the café is a robust chōzubachi (wash basin), with the bowl carved out of a large roughly textured rock, and stone lanterns and trees emerging from thick clipped hedges of azalea and evergreen.

Surrounded by large rough boulders, the powerful waterfall commands the attention of the eyes and the ears, as water gushes over the rocks into the pond.

The raked pea gravel expanse of the private garden is punctuated by islands of long flat stones and mossy mounds topped with rough dark rocks.

A pond of shirakawasuna (white pea gravel) winds its way through a grassy expanse within the main garden at the Art Lake Golf Club.

While the views of the main garden from the clubhouse are appropriately expansive, the dry garden is revealed in a series of contained scenes only visible from the private bathing areas. Islands of stone and lush green ground cover dot the surface of the expanse of carefully raked white shirakawa-suna pea gravel. The islands slowly transform into long strips of stone emerging from the gravel sea, emphasizing movement and creating layers of space in the garden. A tall plastered wall bounds this refined dry garden while separating it from the lush green garden beyond. Although very different in their conception and composition, both gardens at the Art Lake Golf Club invite the visitor to leave behind the day’s troubles and regain a tranquil mind.

The gently curving cap of the carved stone tōrō (lantern) and the closely trimmed hedges contrast the rough landscape of the mountain and waterfall beyond.

The raked gravel “beach” draws the eye along the pond past the tea room and toward the mountains in the distance.

Interior and exterior are connected with a large window opening out to an outdoor bath in the private karesansui (dry) garden.

Many powerful elements—the long waterfall in the lower left, the large rock islands and bridges, and the refined traditional teahouse—come together to create a garden full of movement and energy.

瀑松庭 BAKUSHŌTEI

IMABARI KOKUSAI HOTEL

IMABARI, EHIME PREFECTURE, 1996

The garden at the Imabari Kokusai Hotel completely fills the outdoor spaces, connecting the various hotel spaces visually and physically.

The lobby of the Imabari Kokusai Hotel affords a view of two parts of the Bakushōtei, or Garden of the Great Waterfall and Pine Trees. Immediately adjacent is a karesansui (dry) garden designed as an extension of the lobby. A polished granite curb contains the white shirakawa-suna (literally “White River sand,” or pea gravel) weaving between the rough strips of aji-ishi (a type of granite from Shikoku Island, also known as diamond granite). Low mounds with ground cover and maple trees anchor the dry garden to the building, as the main garden expands out from a level below and slopes upward toward the opposite traditionally designed wing of the hotel.

The strips of rough rock in the dry garden are mimicked in the horizontal layers of pea gravel, rock, and falling water of the main garden. Taking advantage of the natural steep slope of the land, the garden is designed with three separate waterfalls. Shunmyo Masuno designed the movement of the water across the site to have a calming effect. This relaxing atmosphere is punctuated by the largest fall, the thundering Great Waterfall, which “produces echoes deep in the body.”1 This combination of dynamism and calmness is a hallmark of the garden.

Two enormous stone planks join together to create a bridge over the river of pea gravel, allowing visitors to move through the garden to the traditional washitsu (Japanese-style rooms) of the private dining wing.

The stone path and bridge meander through the garden past the smooth gravel river, rocky coastlines, and mossy hillsides toward the traditional wing of the hotel.

Small metal lanterns cast a soft glow over the garden, illuminating the path and creating a picturesque evening scene.

Inspired by the landscape of the Inland Sea, the plantings and rock groupings are arranged among the waterfalls and streams to suggest the nearby scenery. The hotel building surrounds the garden on three sides, with a traditional teahouse tucked into the greenery in the upper garden on the open side. Standing symbolically near the center of the garden, a beautiful red pine acts as focal point. When viewed from anywhere within the hotel or while moving through the garden, the composition of water, rocks, and plants is well balanced and evokes a strong sensory response. The garden is created to change with the seasons—the azaleas bloom in the late spring and early summer, the maple trees from Kyoto turn red in the autumn, while the pine trees remain green throughout the year.

The garden is designed for strolling as well as seated viewing, and a path pieced together with large stones leads through it over a sturdy aji-ishi bridge and through smooth expanses of pea gravel among the rocks and trees. Stepping-stones mark the way through the foliage to the teahouse, where the garden becomes denser and more inwardly focused, and views back to the hotel are blocked by the trees. The design of the roji (inner garden path) leading to the teahouse emphasizes tranquility and simplicity within the dynamism of the larger garden. Near the teahouse, water springs forth from a low carved rock reminiscent of a chōzubachi (water basin) and flows down into the garden, winding through streams and passing over the various waterfalls. At the lowest part of the garden, tucked under the dry garden that extends out from the lobby, the water gathers its force in a thunderous drop over a tall wall of rough rock. The Great Waterfall is framed in the windows of the restaurant on the level below the lobby, visually revealing to patrons what others above can only hear and feel but not see, and creating yet another changing view of this expansive garden.

Conveying a strong sense of movement, the powerful waterfall is juxtaposed with the black pine trees expressing stillness.

Rounded stepping-stones move from the garden under the eaves of the traditional teahouse and up to the small square nijiri-guchi (“crawl-in entrance”).

Connecting the interior of the teahouse to the garden, stepping-stones progress through multiple layers of space embodied by different materials on the ground.

龍門庭 RYŪMONTEI

GIONJI TEMPLE

MITO, IBARAKI PREFECTURE, 1999

A river of raked gravel gives the feeling of expanding beyond the boundaries, while the tall garden wall and a closely trimmed hedge separate the Ryūmontei garden from the main garden at the Gionji temple.

Set within a larger garden at the Gionji Zen temple, a plastered garden wall and trimmed tall hedges contain the space of the smaller Ryūmontei garden. The garden features an arrangement of rocks suggestive of a ryūmonbaku waterfall, from which the garden gets its name. Literally meaning “dragon’s gate waterfall,” the ryūmonbaku represents a carp trying to climb up the cascades and pass through the “dragon’s gate” (ryūmon), an expression referring to disciplined Zen training on the path to enlightenment. The waterfall is one of many typical design devices of traditional Japanese gardens in Ryūmontei, which also include an ocean of raked shirakawa-suna (white pea gravel) dotted with islands of contrasting rough rocks and varied plantings to give color throughout the different seasons. The garden incorporates an additional layer of symbolic meaning, relating specifically to the founding of Gionji. The main tateishi (standing rock) represents the temple founder, Toko Shinetsu, lecturing to his disciple Mito Mitsukuni, also a monk and temple founder. This layer of symbolism, represented through the physical form of certain stones and incorporated into the overall garden design, ties the garden to the history of the temple and makes it unique to that place.

Raked pea gravel follows the contours of the rock “islands” and moss “shoreline,” creating movement and pattern in the foreground of the garden.

The river of gravel in the karesansui (dry) garden starts from the ryūmonbaku (“dragon’s gate waterfall”) near the garden wall and flows under the stone plank bridge toward the temple building.

The garden, designed to be viewed while seated on the tatami (woven grass mats) floor of the sukiya-style Shiuntai reception hall, opens out in front of the viewer in a series of spatial layers connecting the interior of the building to the outside. The exposed wood column-and-beam structure, together with the floor and the eaves of the structure, frames views of the garden. Sliding shoji (wood lattice screens covered with translucent paper) panels at the edge of the tatami-matted room slip away to reveal the deep wood floor of the veranda-like engawa, which aids in connecting the inside space of the building to the exterior space of the garden. Running parallel to the building, a row of dark gravel is partly hidden from view by the engawa. A double row of roof tiles, standing on end, separates the dark gravel from the expanse of smaller white shirakawa-suna that creates the foreground of the garden. The raked pea gravel, flowing around the rock islands and lapping at the edge of a low artificial mound, is an extension of the dry waterfall. Located in a far corner of the garden, on the highest point of the mound, the dry waterfall is a dynamic element, giving a strong sense of movement starting at the high point and flowing down into the white sea of pea gravel. Of the rocks placed within the gravel sea, one low stone is shockingly square in form—the contrasting geometry heightens the viewer’s senses, allowing a deeper awareness of the juxtaposed yet unified nature of the various elements of the garden.

The tateishi (“standing stone”) symbolizing Toko Shinetsu, the founder of Gionji temple, teaching Zen Buddhism to his followers is softly weathered and wrinkled, expressing the wisdom of age.