Читать книгу Zen Gardens - Mira Locher - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

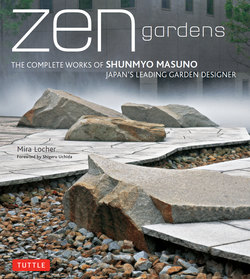

ОглавлениеTwo Pairs of Straw Sandals:

Zen Priest Garden Designer

Shunmyo Masuno

Shunmyo Masuno saws off the branches of bamboo stalks to use in the construction of a garden fence.

“The garden is a special spiritual place where the mind dwells.”1 For Shunmyo Masuno, this is the ultimate meaning of the Zen garden, coming from years of training, both as a Zen Buddhist priest and as a garden designer. These two roles are inseparable in his life, as he describes with the Japanese expression “wearing two pairs of straw sandals” (nisoku no waraji wo haku).2 Garden making is a form of mental and physical training for Masuno, an act of self-cultivation akin to the training of a martial artist. Such acts of self-cultivation are required in the practice of Zen Buddhism.

The oldest son of the head priest at Kenkohji temple in Yokohama, Masuno was almost assured a future as a Zen priest, for the first-born son typically follows in his father’s footsteps. Growing up on the extensive wooded grounds of the temple, Masuno was always near nature, unlike many of his peers, who grew up in urban neighborhoods. When he was eleven years old, he traveled with his family to the ancient capital of Kyoto, where they visited a number of important Zen temple complexes that house significant gardens, including Daisenin (constructed in 1513 CE) and Ryōanji (from 1488 CE). These Zen gardens fascinated him, and he wondered why Kenkohji temple, which was full of trees and other greenery, had no such organized garden space.

By the time he was in junior high school, Masuno was tracing photographs of famous Zen gardens, and in high school he was sketching his own designs. This was the point when he met his future mentor, garden designer Saito Katsuo. Saito had been retained by Kenkohji to shape the temple garden, and Masuno asked for the opportunity to assist him. Although Masuno had no formal training in garden design at that time, Saito must have sensed his enthusiasm and strong work ethic and allowed the young man first to observe his work and later to be his apprentice.

The view from the Saikenji temple entrance leads south through the Baikatei approach garden to the stately sanmon (main gate).

Saito himself had found his way to garden making informally, starting with his father’s work as a gardener. Born in 1893, Saito had only an elementary education, but he liked to study and had a strong intellect. His education came from visiting the traditional gardens in Kyoto and studying them firsthand and then by designing and making gardens himself. Saito lived until 1987, still designing gardens into his nineties, many with the assistance of Masuno.

The lessons that Masuno learned from Saito are numerous, and many were transformative for him. Saito taught him that when the workers are on break having tea, Masuno should come up with thirty different designs for a group of rocks or plants. He instilled in Masuno the need to genuinely and fully understand the site—“if you don’t know the site, you can’t design the garden.”3 Saito emphasized that the way to understand and remember the site is by making sketches and notes, not by taking photographs. For the important elements in a garden, the designer must go to see them in situ, to measure and sketch them where they are found—and then these elements must be placed in the garden directly by the designer. These are the lessons Masuno considers every time he designs a garden.

With the strong foundation he received from Saito’s teaching, Masuno entered the Department of Agriculture at Tamagawa University to study the natural environment. After graduating in 1975, he continued his apprenticeship with Saito, and then in 1979 Masuno began intensive Zen training at Sōjiji temple in Yokohama. In 1982 he founded Japan Landscape Consultants Limited and three years later was appointed assistant priest under his father at Kenkohji temple. In this way, he continues moving ahead with his “two pairs of straw sandals,” sometimes stepping forward with one pair and sometimes the other, but always wearing both.

As Masuno continued his duties as assistant priest and his work as a garden designer, he augmented his understanding of the Japanese sense of aesthetics and values by learning the art of the tea ceremony (chadō or sadō, literally “the way of tea”) along with other traditional arts. He studied the writings of Zen scholars such as thirteenth-century Zen monk and garden designer Musō Soseki and Zen priest Ikkyū Sōjun from the fifteenth century. Both Musō and Ikkyū thought and wrote profoundly about Japanese aesthetics and Zen Buddhism. Ikkyū taught Zen to Murata Jukō, who was integral in the formation of the wabi-cha style of tea ceremony4 by incorporating Zen ideals into the art. Masuno explains, “Murata developed the heart of the host to humbly receive guests as an expression of oneself in Zen. This strong emotional tie of Zen and tea has survived through the centuries.”5

As he continued his training, Masuno developed his own design process steeped in Sōtō Zen principles. In Sōtō Zen, enlightenment (satori) is achieved through disciplined training, including zazen meditation, but also through the completion of everyday tasks. It is the repetition and refinement of these acts that leads to a greater understanding of the self and eventual enlightenment. Masuno states, “Designing gardens for me is a practice of Zen discipline.”6 This correlates to the ideas of Musō Soseki, who wrote in his Dream Dialogues (Muchū mondō), “He who distinguishes between the garden and practice cannot be said to have found the Way.”7 In other words, for the garden designer who is a practitioner of Zen, garden making—both design and construction—must be understood as a vehicle for the attainment of truth in Zen.

The Lhiroma hall at the Suifūso guesthouse opens toward the east for a view of the karesansui (dry) garden representing the kusen-hakkai, the nine mountains and eight seas of the Buddhist universe.

Cloud-like beds of ground cover are interspersed with layers of gravel and roughly textured mountain-like rocks in the Tabidachi no Niwa (Garden for Setting Off on a Journey) in the Yūkyūen garden at the Hofu City Crematorium.

Understanding garden making as an act of Zen Buddhism is an important point when considering the definition of a Zen garden in the twenty-first century. Many gardens in Japan and abroad, especially in the United States and Europe, have been labeled “Zen” or “Zen-style,” but according to Masuno, only those created by a disciplined practitioner of Zen Buddhism truly are Zen gardens. In the West, the often copied simplicity and tranquility of the Zen garden may be sufficient to give an initial appearance of the garden being “Zen.” However, the quality of “Zen” goes beyond mere appearance. Hisamatsu Shinichi, a scholar of Japanese aesthetics has identified seven different characteristics particular to Zen arts: asymmetry (fukinsei), simplicity (kanso), austere sublimity or lofty dryness (kokō), naturalness (shizen), subtle profundity or deep reserve (yūgen), freedom from attachment (datsuzoku), and tranquility (seijaku).8 These are qualities that result from the mind (both the mental state and the spirit or kokoro) of the artist and the process of designing. Masuno notes that in the West, gardens often are an expression of an interior idea and are treated as rooms.9 This is very different than his own process of design, which begins by the designer emptying his mind and listening to the site and the context in order to allow the design and its inherent aesthetic qualities to grow from the place rather than be applied to it.

“Zen aims to teach one how to live, so it has no form,” notes Masuno.10 Yet from the late twelfth century, Zen monks began to experiment with artful expressions of the Zen mind. The initial medium they chose was ink brush painting (sumi-e). At the same time, Zen Buddhist gardens were designed based on Chinese poetry and garden design. When the essence of Zen expressed through sumi-e was combined with garden making, the result was the dry landscape garden (karesansui).11 The karesansui garden, the most renowned of which is the garden at Ryōanji that Masuno viewed as a boy, is now the garden type most closely associated with Zen Buddhism. However, by no means are all Zen gardens dry landscapes. Water is a key element in many of Masuno’s gardens, as well as those of his influential predecessors, including Musō Soseki, who designed the Zen garden at Saihoji temple (from 1339 CE), famous for the thick carpet of moss covering the banks of its quiet stream and pond.

Many Zen gardens are constructed within small contained spaces, such as the Ryōanji garden, which is built on the south side of the abbot’s quarters, with garden walls on the other three sides. These diminutive gardens typically convey important Zen principles such as emptiness (kyo) and infinite space. Emptiness often is expressed as yohaku no bi, literally the “beauty of extra white,” referring to the beauty in blankness or emptiness. “Emptiness is the fountain of infinite possibilities.”12 Infinite space is especially powerful when expressed within a contained area. “Large revelations often occur in very small places, sometimes as the result of a radical shift in scale and perspective.”13 Although small Zen gardens may be spaces of revelation, the size of the garden alone does not define it as Zen.

Common to all Zen gardens is the incorporation of the “heart” (kokoro) of the rocks, trees, and other materials that comprise them.14 The word that Masuno uses to express the “heart” of the materials, kokoro, also can be translated to mean “mind” or “spirit.” According to Zen Buddhism, each material has its own spirit, which must be respected. Therefore each rock or tree must be understood for its own unique characteristics. When Masuno speaks of his gardens being “expressions of [his] mind,” he is referring to his own kokoro—which is rooted not in the head but in the heart.15 Masuno’s gardens, therefore, are a dialogue between his kokoro and the kokoro of each of the elements in the garden.

The idea of garden design as a dialogue between the designer and the elements in the garden is clearly stated in the first known Japanese garden manual, the eleventh-century Sakuteiki (Memoranda on Garden Making). “Ishi no kowan wo shitagau,” or “Follow the request of the stone,”16 implies the requirement to have a dialogue with the elements in the garden in order to have a complete understanding of the unique character of each element. Philosopher Robert E. Carter notes, “In Western cultural climates, one would be looked at with the greatest of suspicion upon speaking of initiating a dialogue with rocks or plants.”17 It is this dialogue between the designer and the rocks and trees in the Zen garden that creates timeless beauty and profound spiritual depth in the garden. Masuno notes,

The carved stone chōzubachi (water basin) in the Fushotei garden rests on a rough rock base at the edge of the engawa (veranda) of the Renshōji temple reception hall.

Obviously, there is a great difference between a form that only sets out to be beautiful and one in which body and soul are united at the time of its creation. Even if the completed forms are very nearly the same, the impression of the viewer should differ greatly, too, because the mental energy that exists within the work is different:... if a garden has no soul, then even though it may catch the attention of many people for a time, they will completely forget about it as soon as something new comes along.18

As “ishi no kowan wo shitagau” suggests, this dialogue with the elements of the garden initially focused on the choice and siting of rocks. Rocks have long been revered in both Japan and China, where the prototypes for Japanese gardens developed. Before Buddhism entered Japan from China and Korea in the sixth century, rocks were venerated in Japan in the vernacular Shintō religion. They were believed to be “the medium of divine connection.”19 Deities were understood to reside in natural features, such as rocks known as iwakura (literally “rock seat”). These rocks often had distinctive features relating to their size, shape, color, or markings. These unique qualities distinguished the rocks as special, and therefore they were treated with great respect.

From ancient times in China, rocks were afforded a similar respect, as they were understood to contain the essential energy of the earth, the qi (or ch’i, ki in Japanese). These rocks were placed in gardens, first in China and later in Japan, so people could enjoy them and contemplate their power. “The garden thereby becomes a site not only for aesthetic contemplation but also for self-cultivation, since the qi of the rocks will be enhanced by the flows of energy among the other natural components there.”20

Yukimi-shōji (“snow-viewing” sliding screens) reveal a view to mountain-like rocks backed by a k Metsuji-gaki (“lying cow–style” fence) made of bamboo in the courtyard garden at Hotel Le Port.

These early leanings in both China and Japan toward understanding and respecting rocks for their unique qualities naturally led to rocks playing an important role in Japanese gardens. Garden making started in Japan with the introduction of Buddhism from China and incorporated Chinese cultural ideas and forms. Therefore, the first gardens in Japan were much like their Chinese counterparts. Gardens built for the court nobility featured meandering streams, ponds, and distinctive rock outcroppings. Initially the garden forms were close imitations of Chinese garden types, but by the end of the Heian period (794–1185 CE) in Japan, the Mahayana Buddhism that had been introduced in the mid-sixth century gave way to the Pure Land school of Buddhist thought, and garden designs changed to reflect these new ideals.

Pure Land gardens were paradise gardens. Built for aristocrats on their sprawling estates, a typical paradise garden featured a large pond on the south side of a shinden-style building, with a central hall flanked by pavilions extending into the garden. Small islands, sometimes connected to the shore by bridges, punctuated the smooth surface of the pond. These gardens were designed to be enjoyed both by moving through the space, on foot or by boat on the pond, as well as by viewing from the adjacent mansions. The relationship between the surrounding shinden buildings and gardens was integral to the designs. Exotic and unique plants and rocks filled these gardens, evoking the sense of a sumptuous paradise, the Buddhist Pure Land.

By the mid-thirteenth century, gardens in Japan like those designed by Musō Soseki at the Saihoji temple began to show a change from an image of an otherworldly paradise to finding delight in splendors more closely related to this life. Rocks continued to play a major role in these gardens, and the first hints of the Zen gardens appeared as dry waterfalls constructed of rocks in gardens like Saihoji. By the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries (the end of the Kamakura period and into the Muromachi era), Buddhist priests were active in designing and making gardens. These priests became known as ishitateso (“stone-laying monks”), for although they were charged with designing the complete garden, finding appropriate rocks and siting them properly in the garden were considered their primary responsibilities. This name for the garden makers proves the continued importance of rocks in the gardens in Japan.

A river of rocks runs under an asymmetrical stone bridge, spanning banks of lush moss in the Fushotei garden at the Renshōji temple.

Many of the gardens from the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, including those at Kinkakuji (constructed in 1397 CE) and Ginkakuji (from 1482 CE), known as the Golden Pavilion and Silver Pavilion respectively, still showcase aspects of Pure Land aesthetics, such as pleasure pavilions set within extensive gardens. Paths lead between grouping of rocks and plants, passing ponds and passing over streams on stone or wood bridges. But by the late fifteenth century, gardens such as Ginkakuji started to incorporate other design principles, including miniaturization and compositions of dry rock arrangements, which became hallmarks of Zen gardens.

Zen Buddhism took hold in Japan during the Muromachi period (1392–1568 CE) and began to influence the arts. Buddhism had been introduced into Japan partly for its system of education, which included a written language. Temples were places of learning, and monks spent time studying Buddhist texts. The arts, including painting and sculpture stimulated by Chinese Buddhist aesthetics, flourished at the temples. Under Zen Buddhism, the arts developed distinctively, reflecting the ideas of discipline of the mind and the body that were important in Zen. Enlightenment came from within through strict training. Zen focused on understanding (and through the arts, expressing) the spirit embodied in all things. Meditation was the vehicle for achieving this, and artistic practices, like brush painting, served as training. In the Zen arts, ornament was eschewed in favor of simplicity, and a tendency toward abstraction developed.

During this time Zen monks, inspired by Chinese Sung era paintings of craggy mountains and winding rivers, began to create gardens reflecting the landscapes in the paintings. These gardens often were made using only a few materials—rocks, pea gravel, and perhaps a few plants. By the late fifteenth century, the karesansui (literally, “dry mountain water”) gardens at Daisenin at the Daitokuji temple and at Ryōanji, two of the most well-known gardens of this style, expressed landscapes very abstractly utilizing miniaturization and symbolism. Rock groupings were situated to represent landscape elements such as islands and waterfalls, but they also could be representational, depicting an image of sacred Mount Shumisen, the center of the Buddhist universe, for example, or perhaps even the Buddha. These karesansui gardens were not used for entertainment and enjoyment as previous gardens had been. Rather they had strong religious connotations and were used by the monks for meditation. Garden historian Loraine Kuck describes the Zen ink brush painting that inspired these gardens—but she easily could be describing the gardens themselves. “Simple as were these materials, in the hands of a master they were capable of suggesting the mistiness of distant mountains or rivers, the bold forms of rocks and crags, the dark textures of pines, and the whiteness of a waterfall.”21

A sculpted stone marker, one side roughly textured with the marks of the artist’s hand-work and the other side smoothly polished to a reflective surface, expresses the connection between old and new at the Opus Arisugawa Terrace and Residence.

Another garden type that developed under the influence of Zen Buddhism was the tea garden. As the wabi-cha style of tea became fully developed in the late sixteenth century (the Momoyama period), ceremonial teahouses and gardens were constructed to fit into existing estates, often tucked into an unused corner. These gardens typically express a refined or restrained nature and are designed around a pathway, the roji (literally “dewy ground”), leading from an entry gate past a waiting bench to a small teahouse. “The roji was a carefully designed environment, a corridor whose true purpose was to prompt the mental and spiritual repose requisite to the tea gathering.”22

Although the karesansui Zen gardens moved away from replicating known landscapes in miniature form to representing an abstract idea of a landscape, and the more naturalistic tea gardens acted as a series of physical and mental thresholds, the key to the design of all Zen gardens was the human attitude to nature. From early times, the Sakuteiki had advised to design a garden by “Paying keen attention to the shape of the land and the ponds, and create a subtle atmosphere, reflecting again and again on one’s memories of wild nature.”23

Wild nature in Japan can mean steep heavily forested mountains, rivers flowing swiftly along rocky banks, rough winding coastlines, and small islands full with greenery. These are some of the natural elements that inspire garden designers, but the Japanese attitude toward nature also is an important influence. This notion is deeply rooted in the Shintō reverence for nature as well as the idea supported by both Shintō and Buddhist teachings that humankind is not separate but rather a part of nature, combined with a profound respect for the power inherent in nature. Shintō focuses on particular objects in specific places, like the sacred iwakura. However, the typhoons, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and tsunami that are part of life in the island country categorically demonstrate nature’s force—a force with which the Japanese people have learned to coexist. Thus the attitude toward nature is very specific to an unchanging place—a rock or a waterfall, for example—while also being bound up with changing and unpredictable natural conditions. The Japanese garden “displays a design logic which is intimately bound up with the genius loci of the Japanese landscape—in other words, with the essence of the country as it appears to the human imagination.”24 This essence incorporates both elements understood to be mostly unchanging together with those that are transient and impermanent.

The design of the Fūma Byakuren Plaza at the National Institute for Materials Science expresses the spirit of the scientists working nearby and features a meandering river of small rocks connecting gridded and grass-covered surfaces.

A sharp peninsula of stone projects over a still reflecting pool representing the Pacific Ocean in the fourth-story garden at the Canadian Embassy in Tokyo.

“The Japanese find beauty in impermanence, the constant transformation. The light and shadow, winds, the flowing of time, the changing of seasons.... I find it so appealing that we are part of this vast nature, with its state of constant change and uncertainty of the times.”25 This “constant transformation” or impermanence of all living things is expressed by the Buddhist concept of mujō (transience). Mujō is integrated into every garden with the seasonal transformations of the flowering plants and colored leaves of the trees, as well as the ever-changing shadows cast by the trees and rocks. While transience is an important principle in both garden design and garden viewing, other aesthetic concepts, such as the seven identified by Hisamatsu Shinichi also are at work in gardens. Of those, yūgen is important in connecting the viewer of the garden to the kokoro—the spirit—of the garden elements. Yūgen has been translated as “subtle profundity,”26 “a profound and austere elegance concealing a multilayered symbolism,”27 and “the mood of great tranquility.”28 “Yūgen is called into being by atmosphere, one of hazy unreality that creates in a mind attuned to it the feeling of kinship with nature, the sense of one’s spirit merging with the spirits of other natural things and the eternal behind them all.”29

Without training and study, yūgen, like many other Zen aesthetic principles, is not an easy concept to grasp. According to Masuno, the creation of a garden or other artistic work embodying such principles, such as the choice of rocks and plants to create the atmosphere of the Zen garden, comes only through kankaku (feeling or sense) and kunren (training or discipline).30 The point of incorporating these principles is not for the sake of the principles themselves, but rather to create a place where people can leave behind the yutakasa (richness, abundance) of everyday life that is strongly focused on goods and consumption. Instead, while experiencing the garden, visitors can encounter their “kokoro no yutakasa” (the richness of their spirit).31

The contrasting colors and forms of two rocks placed in front of a dark stone wall at the Nassim Park Residences evoke the feeling of the power of nature.

Whether designing a traditional garden, a modern garden, or a garden overseas, creating Zen gardens that allow people to reflect on how to live their lives well every day is Shunmyo Masuno’s goal. "Zen is ultimately a way of discovering how one should best live. By viewing a garden, viewers question themselves if they are walking the correct path. They search for the unmoving truth inside the garden, the place where serenity and calmness are reclaimed. The delusions and the answers are all within ourselves."32