Читать книгу Zen Gardens - Mira Locher - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

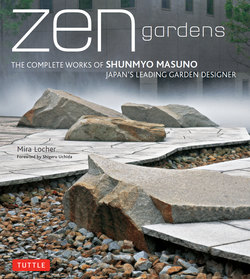

ОглавлениеFOREWORD BY

SHIGERU UCHIDA

This is entirely my own personal opinion: however, by coming into contact with many designs, I have become aware that there are two directions for design themes. They are the way to grasp a “thing” or “object” as a subject and the way to consider a “relationship” as a subject. Supposing we call the former “object as precedent,” the latter can be called “relationship as precedent.” Japanese culture is that in which everything is “relationship as precedent.”

Many Western cultures can be seen as cultures with “object as precedent.” However, in that case the “thing” is the subject; by no means is it the predicate. In relational philosophy, formerly a relationship firstly had independent content, and it was thought that within that content, that relationship came into being. However, recently it is thought that it is “unequivocal only because of the relationship.”

The “relationship as precedent” is predicate logic. First of all, more than the subject, the predicate is valued. Independent meaning is removed from all things, then things come into existence only in the situation they fall into and in the circumstance of a relationship. Things do not always display their fixed nature. Depending on the situation things fall into and the circumstances, even if they are the same, they create different meanings.

The first obstacle encountered in symbolic logic is probably when the concept of subject and predicate appeared within “predicate logic.” In the words “I am a designer,” first of all “I” exists, whether that existence is “designer” or “man” or else “Japanese person” is realized as a modifier or as a predicate. In any case, to begin with, there is a subject, one’s identity is ensured. With regard to that, a pattern of something that can be described is in the background.

However, in predicate logic it becomes “subject is change.” If that is the case, the situation changes completely. Namely, where the modifier of being a “designer” does not change, but the changing of “I,” which becomes the subject, is required. In other words, in “predicate logic” the important thing is the modifier “designer.” The meaning of this content becomes the modifier. In Japanese culture, a relationship is such.

The rock arrangements in the gardens of Masuno Shunmyo also are thus. In regard to rocks as a subject, that predicate relationship of how they are arranged is important. The project of the Kantakeyama Shinen at the Samukawa shrine, through phase one and phase two, is an enormous undertaking. This kind of garden project is not formed with just one point of view. Most essential in Masuno’s garden design is the division of land. Namely, depending on the spatial composition of the site, first the framework is formed. Here is a chisenkaiyushiki-teien (pond stroll garden), and attached to it are a chaya (tea pavilion) and chashitsu (teahouse). Furthermore, there is a Zen garden, and as an extension of the main hall [of the shrine], there also are the Kantakeyama mountain, a chinju no mori (sacred grove), and the Namba no Koike pond. A major theme is how to create a relationship between each of these things that has its own individual meaning. Moreover, on top of these relationships, each of their parts also comes into existence. The relationships of these parts and the overall relationship of many elements—these are composed depending on Masuno’s studied intention.

For example, the relationship of the ryūmonbaku [literally, “dragon’s gate waterfall”] and the stone bridge depends on the combination of rock arrangements and water, giving the viewer a profound impression and sense of grandeur. Also the contrast of the natural rock of the ryūmonbaku and the rectilinearly hewn stone bridge produces a feeling of tension in these surroundings.

Also more pure than anything is the scenery from the Warakutei tea pavilion (chaya). Compared to the teahouse (chashitsu), that pleasure of the tea pavilion, the abounding sense of entertainment in the variation of the pond garden, is expressed. Even so, Masuno’s architectural skill truly is to be admired. To say what is good, it is the superb relationship between the garden and the architecture. This is because it is architecture made by the designer with the garden as the theme. It is easy if we say the relationship to the garden is superb, but that atmosphere exists because the architecture does not forcibly assert itself, yet it isn’t restrained. The relationship of the architecture and the pond as viewed from the garden is something truly beautiful. Also, when the garden is viewed from the interior horizontal opening, that horizontality comes together with the garden and rushes inside the room.

I also want to verify [these relationships in] other projects, but I’ll keep it to this. What one can feel from Masuno’s projects regards “relationality” and “object-ness.” However, so there is no misunderstanding here, in many cases depending on their complementarity, things are completed. What is important here is which thinking comes first. In all Japanese culture, relationality comes first.

Nighttime lighting softly illuminates the rock arrangements and raked gravel of the Chōsetsuko courtyard garden at the Ginrinsō Ryōkan.