Читать книгу Amy, My Daughter - Mitch Winehouse - Страница 12

Оглавление4 FRANK – GIVING A DAMN

In the autumn of 2002, EMI flew Amy out to Miami Beach to start working with the producer Salaam Remi. By coincidence, or maybe it was intentional, Tyler James was also in Miami, working on another project; Nick Shymansky made up the trio. They were put up at the fantastic art-deco Raleigh Hotel, where they had a ball for about six weeks. The Raleigh featured in the film The Birdcage, starring Robin Williams, which Amy loved. Although she and Tyler were in the studio all day, they also spent a lot of time sitting on the beach, Amy doing crosswords, and danced the night away at hip-hop clubs.

Because she had gone to the US to record the album, I wasn’t all that involved in Amy’s rehearsals and studio work, but I know she adored Salaam Remi, who co-produced Frank with the equally brilliant Commissioner Gordon. Salaam was already big, having produced a number of tracks for the Fugees, and Amy loved his stuff. His hip-hop and reggae influences can be clearly heard on the album. They soon became good friends and wrote a number of songs together.

In Miami Amy met Ryan Toby, who had starred in Sister Act 2 when he was still a kid and was now in the R&B/hip-hop trio City High. He’d heard of Amy and Tyler through a friend at EMI in Miami and wanted to work with them. He had a beautiful house in the city where Amy and Tyler became regular guests. As well as working on her own songs, Amy was collaborating with Tyler. One night in Ryan’s garden, they wrote the fabulous ‘Best For Me’. The track appears on Tyler’s first album, The Unlikely Lad, where you can hear him and Amy together on vocals. Amy also wrote ‘Long Day’ and ‘Procrastination’ for him and allowed him to change them for his recording.

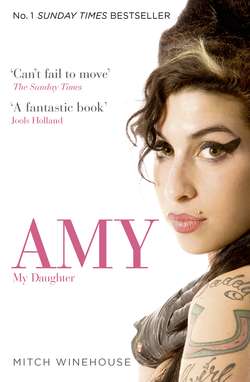

Amy sent me this Valentine’s Day card from Miami, while recording tracks for Frank in 2003.

By the time Amy had returned from Miami Frank was almost in the can but, oddly, though she’d signed with EMI for publishing nearly a year earlier, she still hadn’t signed with a record label. I kept asking anyone who’d listen to let me hear Amy’s songs, and eventually 19 gave me a sampler of six tracks from Frank.

I put the CD on, not knowing what to expect. Was it going to be jazz? Rap? Or hip-hop? The drum beat started, then Amy’s voice – as if she was in the room with me. To be honest, the first few times I played that CD I couldn’t have told you anything about the music. All I heard was my daughter’s voice, strong and clear and powerful.

I turned to Jane. ‘This is really good – but isn’t it too adult? The kids aren’t going to buy it.’

Jane disagreed.

I rang Amy, and told her how much we’d loved the sampler. ‘Your voice just blew me away,’ I said.

‘Ah, thanks, Dad,’ Amy replied.

Apart from the sampler, though, I still hadn’t heard the songs that were on the short-list for Frank and Amy seemed a bit reticent about letting me listen to them. Maybe she thought lyrics like ‘the only time I hold your hand is to get the angle right’ might shock me or that I’d embarrass her. I teased her after I’d finally heard the song.

‘I want to ask you a question,’ I said. ‘That song “In My Bed” when you sing—’

‘Dad! I don’t want to talk about it!’

Amy came over to Jane’s and my house when she was sorting out the tracks for Frank. She had a load of recordings on CDs and I was flicking through them when she snatched one away from me. ‘You don’t want to listen to that one, Dad,’ she said. ‘It’s about you.’

You’d have thought she’d know better. It was a red rag to a bull and I insisted she played ‘What Is It About Men’. When I heard her sing I immediately understood why she’d thought I wouldn’t want to listen to it:

Understand, once he was a family man

So surely I would never, ever go through it first hand

Emulate all the shit my mother hates

I can’t help but demonstrate my Freudian fate.

I wasn’t upset, but it did make me think that perhaps my leaving Janis had had a more profound effect on Amy than I’d previously thought or Amy had demonstrated. I didn’t need to ask her how she felt now because she’d laid herself bare in that song. All those times I’d seen Amy scribbling in her notebooks, she’d been writing this stuff down. The lyrics were so well observed, pertinent and, frankly, bang on. Amy was one of life’s great observers. She stored her experiences and called upon them when she needed to for a lyric. The opening lines to ‘Take The Box’ –

Your neighbours were screaming,

I don’t have a key for downstairs

So I punched all the buzzers…

– refer to something that had happened when she was a little girl. We were trying to get into my mother’s block but I’d forgotten my key. A terrible row, which we could hear from the street, was going on in one of the other flats. My mother wasn’t answering her buzzer – it turned out that she wasn’t in – so I pressed all of the buzzers hoping someone would open the door.

Of course the song had nothing to do with me buzzing buzzers: it was about her and Chris breaking up. But I was amazed that she could turn something so small that had happened when she was a kid into a brilliant lyric. For all I knew, she’d written it down when it had happened and, eight or ten years later, plucked it out of her notebook. She was a genius at merging ideas that had no obvious connection.

The songs on the record were good – everyone knew it. By 2003, with the record all but done, loads of labels were desperate to sign her. Of all the companies, Nick Godwyn thought Island/Universal was the right one for Amy because they had a reputation for nurturing their artists without putting them under excessive pressure to produce albums in quick succession. Darcus Beese, in A&R at Island, had been excited about Amy for some time, and when he told Nick Gatfield, Island’s head, about her, he too wanted to sign her. They’d heard some tracks, they knew what they were getting into, and they were ready to make Amy a star.

Once the record deal had been done with Island/Universal, suddenly it all sunk in. I sat across from Amy, looking at my daughter, and trying to come to terms with the fact that this girl who’d been singing at every opportunity since she was two, was going to be releasing her own music. ‘Amy, you’re actually going to bring out an album,’ I said. ‘That’s brilliant.’

For once, she seemed genuinely excited. ‘I know, Dad! Great, isn’t it? Don’t tell Nan till Friday. I want to surprise her.’

I promised I wouldn’t, but I couldn’t keep news like this from my mum and phoned her the minute Amy left.

When I think about it now, I realize I took Amy’s talent for granted. At the time I actually thought, Good, looks like she’s going to make a few quid out of this.

Amy’s record company advance on Frank was £250,000, which seemed like a lot of money. But back then some artists were getting £1 million advances and being dropped by their label before they’d even brought out a record. So, although it was a fortune to us, it was a relatively small advance. She had also received a £250,000 advance from EMI for the publishing deal. Amy needed to live on that money until the advances were recouped against royalties from albums sold. Only after that had happened could she be entitled to future royalties. That seemed a long way off: how many records would she need to sell to recoup £500,000? A lot, I thought. I wanted to make sure that we looked after her money so it didn’t run out too quickly.

When Amy first got the advance she was living with Janis in Whetstone, north London, with Janis’s boyfriend, his two children and Alex. But as soon as Amy’s advances came through she moved into a rented flat in East Finchley, north London, with her friend Juliette.

Amy understood very quickly that if her mum and I didn’t exert some kind of financial control she’d go through that money like there was no tomorrow. I had no problem with her being generous to her friends – for example, she wouldn’t let Juliette pay rent – but she and I knew that I needed to stop her frittering the money away. She was smart enough to understand that she needed help.

Amy and Juliette settled into the flat and enjoyed being grown-up. I would often drop by. I’d left my double-glazing business and had been driving a London black taxi for a couple of years. On my way home from work, I’d go past the end of their road and pop in to say hello, but Amy always insisted I stay, offering to cook me something.

‘Eggs on toast, Dad?’ she’d ask.

I’d always say yes, but her eggs were terrible.

And we’d sing together, Juliette joining in sometimes.

It was around this time that I first suspected Amy was smoking cannabis. I used to go round to the flat and see the remnants of joints in the ashtray. I confronted her, and she admitted it. We had a big row about it and I was very upset.

‘Leave off, Dad,’ she said, and in the end I had to, but I’d always been against any kind of drug-taking and it was devastating to know that Amy was smoking joints.

* * *

As time progressed, everyone at 19, EMI and Universal was so enthusiastic about Frank that I began to believe it was going to sell and that maybe, just maybe, Amy was going to become a big star. On some nights when she had a show, I’d go and stand outside the place where she was playing, like Bush Hall in Uxbridge Road, west London. Her reputation seemed to grow by the minute. I’d listen to what people were saying as they went in, and they seemed excited about seeing her.

Afterwards Amy and I would go out for dinner, to places like Joe Allen’s in Covent Garden, and she would be buzzing, talking to other diners, having a laugh with the waiters. In those days she liked performing live – as a virtual unknown she felt no pressure and simply enjoyed herself; she was always happy after a show, and I loved seeing her like that.

Her voice never failed to blow audiences away, but she needed to work on her stagecraft. Sometimes she’d turn her back on the audience – as though she didn’t want to face them. But when I asked if she enjoyed performing, she’d always say, ‘Dad, I love it,’ so I didn’t ask anything more.

In the months leading up to Frank’s release, Amy did lots of gigs. Playing live meant auditioning a band to perform with her, and 19 introduced her to the bassist Dale Davis, who eventually became her musical director. Dale had already seen Amy singing at the 10 Room in Soho and remembers her flashing eyes – ‘They were so bright’ – but he didn’t know who she was until he went to that audition. Oddly enough, he didn’t get the job at that point, but when her bass-player wanted more money, Dale took over.

Amy and her band played the Notting Hill Carnival in 2003. It’s always a very hard gig – the crowd is demanding – but when I spoke to Dale later, he said that Amy had carried the whole thing on her own. She didn’t need a band. He was knocked out by how great she was, just singing and playing guitar. She might not have been technically the greatest guitarist ‘but no one else could play like Amy and fit the singing and playing together’. Her style was loose, but her rhythm was good and the songs were so strong that it all locked together. As Dale says, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards are not great guitarists: it’s all soul and conviction. ‘You just do it, and throughout the years of doing it you get there.’

Still, Amy’s live performances were not without their struggles. One gig I particularly remember was in Cambridge where she was supporting the pianist Jamie Cullum. Amy and Jamie hit it off and became friends, but when you’re young and just starting out, it’s an unenviable task to be the support act. That night people had come to see Jamie, not her – very few people in the Cambridge audience had even heard of Amy – and initially they weren’t very responsive. But when they heard her sing, they started to get into it. One of the most difficult things about being the support act is knowing when to stop and, as that night showed, Amy didn’t. I don’t blame her because she was inexperienced. Perhaps her management should have clued her up.

Amy ended up doing about fifteen songs, which was probably eight too many. By the end, people were getting restless. I could hear them saying, ‘How much longer is she going to be?’ and ‘What time does Jamie Cullum come on?’ Even the people I’d heard say, ‘She’s good,’ were fed up and wanting to see the act they’d paid for – Jamie Cullum. Of course, being me, I ended up shouting at people to shut up and nearly had a fight with someone.

Much to the audience’s relief, Amy finished the set, but instead of going backstage, she climbed down and came to stand with us. We all watched Jamie and really enjoyed his performance – Amy cheered, clapped and whistled all the way through. She was always very generous with other performers.

With more gigs, and promotional events linked to the imminent release of Frank, Amy wanted to start planning ahead. As the lease on her flat in East Finchley was about to expire, Janis and I sat down with her and asked her what she wanted to do. She said she’d like to buy a place rather than keep renting, and I agreed with her. A flat would be a great investment, particularly if her singing career ever went wrong. Remember those days before the recession? You could buy a flat for £250,000 one day and sell it the next for £275,000 – I exaggerate a bit, but the property market was booming.

Amy loved Camden Town and we soon found a flat there that she liked in Jeffrey’s Place. It was small and needed some work, but that didn’t matter because all of her favourite places were in walking distance. This was where she wanted to be and the flat had a good feel to it. To get to it, you had to be buzzed through a locked gate, which reassured Janis and me: Amy would be quite safe there. The flat cost £260,000. We put down £100,000 and took out a £160,000 mortgage, which left a good bit of money from the advances. I sat down with Amy and worked out a budget with her. All of the household bills and the mortgage would be paid out of her capital and she would have £250 a week spending money, which she was quite happy with. If she needed something in particular she could always buy it, but that didn’t happen too often.

In those days Amy was quite sensible about money. She knew that she had a decent amount to live on and that we were looking after her interests. She also knew that if she developed lavish habits, her funds would soon run out. Although Amy was a signatory on her company’s bank account, she wanted a safeguard put in place to ensure that she couldn’t squander her money so we agreed that any cheque had to be signed by two of the signatories to the account. The signatories were Amy, Janis, our accountant and myself. It would be an effective brake, we hoped, because Amy was generous to a fault.

When it was time to put the credits together for Frank – who had done what on this song, who had written what on that song – in the spring of 2003, her generosity was evident again. Nick Godwyn, Nick Shymansky, Amy and I crowded round her kitchen table to sort it out – there had been a leak in the bathroom the night before and the lounge ceiling had fallen in. So much for the glamorous life. (Mind you, a year on, the place looked like a bomb had hit it.)

Nick Shymansky started off. ‘Right. How do you want to divide up the credits for “Stronger Than Me”?’

‘Twenty per cent to …’ Amy began, and she’d name someone and Nick would ask her why on earth she’d want to give that person 20 per cent when all they’d done was come to the studio for an hour and suggest one word change. While it was certainly important to credit people for what they had done, and ensure that they were paid accordingly, she was giving away percentages to people for almost nothing. Amy was brilliant at maths, but I swear, if she’d had her way, she would have given away more than 100 per cent on a number of songs.

* * *

On 6 October 2003, three weeks prior to the release of Frank, the lead single, ‘Stronger Than Me’, hit the shops and peaked, disappointingly, at number seventy-one in the UK charts – it turned out to be the lowest-charting single of Amy’s career. When the album came out on 20 October 2003, it sold well, eventually making it to number thirteen in the UK charts in February 2004. It was also critically acclaimed, and sales were boosted later in 2004 when it was short-listed for a Mercury Music Prize, and Amy was nominated for the BRIT Awards for Best British Female Solo Artist and Best British Urban Act.

I devoured all of the reviews, and don’t recall anything negative, although the hip-hop/jazz mix confused some at first. The Guardian wrote, ‘Sounds Afro-American: is British-Jewish. Looks sexy: won’t play up to it. Is young: sounds old. Sings sophisticated: talks rough. Musically mellow: lyrically nasty.’

I thought that Frank, which is still my favourite Amy album, was fantastic. One of the reasons I love it is because it’s about young love and innocence, and it’s funny, comical and has brilliantly observed lyrics. It wasn’t written out of the depths of despair. I still love listening to Frank and play it often. I was so proud of my little girl.

Unfortunately Amy didn’t hear things quite as I did. She had mixed feelings about the final cut and complained that the record company had included some mixes that she had told them she didn’t like. It was partly her fault: she’d missed a few of the editing sessions, in typical Amy fashion.

We were in the kitchen at her flat in Jeffrey’s Place, having a cup of tea, and the window was open. The builders working next door turned their radio up loud and one of the songs from Frank was playing.

‘Shut the window, Dad, I don’t want to hear that,’ Amy said.

It had been on my mind for a while to ask her, so I said, ‘Were you thinking about anyone in particular when you wrote “Fuck Me Pumps”?’ She shook her head. ‘There’s the line … What is it? Hang on … Let me have a look at the CD. Where is it?’

‘I don’t even know if I’ve got one, Dad.’

‘What? You haven’t got a copy of your own album?’

‘No, I’m done with it. It was all about Chris, and that’s in the past. I’ve forgotten about it, Dad. I’m writing other stuff now.’

This was news to me. I’d never seen this side of Amy, the way she could put something so deeply personal and important behind her, as if it didn’t matter any more. Nevertheless, she continued to promote Frank, and later that year she performed at some very prestigious venues: the Glastonbury Festival, the V Festival and the Montreal International Jazz Festival. No matter what, her music and her family came first. But her other priorities then were like so many other girls of her age – clothes, boys, going out with her friends, her image and style – she was, after all, a woman in her early twenties.

She may have been dismissive about Frank but things happened with the album that made her realize it was special, like when ‘Stronger Than Me’, which she’d written with Salaam Remi, won the Ivor Novello Award for Best Contemporary Song Musically and Lyrically. The Novellos mattered to Amy: her peers, other composers and writers voted to decide the winners. Amy went to the ceremony and rang me to tell me she’d won. I was halfway down Fulham Road, taking someone to Putney in my taxi, when she called.

‘Dad! Dad! I won an Ivor Novello!’

I was so excited but I still had to drive this chap home and finish my shift. By then it was late and I had no one to bother so I went and woke up my mum. ‘Amy’s won an Ivor Novello!’

She was as pleased as I was.

One disappointment we all shared was that Frank wasn’t initially released in America. 19 felt that Amy wasn’t ready for the States. They said that you only get one shot at breaking the States and this wasn’t the time, mostly because, in their view, her performance level wasn’t strong enough.

Frustrating though it was, they were probably right. At this time Amy was still playing guitar onstage and 19 wanted to get the guitar out of her hands: she was always looking down at it instead of engaging with the audience. Sometimes it was as if they weren’t there and she was singing and playing for her own amusement. Her voice was great, but she wasn’t delivering a performance: she needed coaching in how to give the best to her audiences. Her act needed refining before she took it to the States.

They told Amy that she had to communicate with the audience and the best way to do that was to show them she was having a good time. This, though, was what she struggled with. She loved singing and playing to family and friends, but as the gigs got bigger, so did the pressure, highlighting the fact that she wasn’t a natural performer. As Amy was outwardly so confident, no one imagined that inside she harboured a fear of being onstage, and that as she played in front of ever-increasing crowds, the fear didn’t go away. Over time it became worse. But she was so good at concealing it that even I wasn’t aware of how hard this was for her. Quite often, during a song, she’d still commit the cardinal sin of turning her back on the audience. I’d be watching and want to shout at her, ‘Speak to the audience, they love you. Just say, “Hi, how you doin’? You all havin’ a good time?”’

Amy never did figure out how to deal with stage fright. While she wasn’t physically sick, as some performers are, she sometimes needed a drink before she went on. Maybe even needed to smoke a little cannabis, but I don’t know for sure, because she wouldn’t have done that in front of me. What I certainly didn’t know and, with hindsight, perhaps I should have seen the warning sign for, was that she was starting to drink a lot more than was good for her, even then.

As a teenage girl she’d suffered from a few self-esteem issues – what teenager doesn’t? – but I really don’t believe that was at the root of her stage fright; by the time she was performing regularly her self-esteem issues had gone. But 19 were right: she wasn’t ready to go to America. Before that Amy needed to work hard on her act and it would take time. Talking to the audience and showing them she was enjoying herself came later, and even when it did, I don’t think it was ever natural. To me, she always looked uncomfortable when she was doing it.

It wasn’t easy to talk to her about a performance; after maybe a couple of days I could say things about what she was and wasn’t doing, but I had to be careful. Amy wasn’t so much strong-willed as cement-willed, and she did things her way.

As the promotional gigs continued, her management started to talk about a second album. There were still some good songs that hadn’t been included on Frank. One in particular was ‘Do Me Good’. I told Amy that I thought it should go on the second album because it was fantastic, but she didn’t think so and reminded me of something she’d told me once before: ‘That was then, Dad. It’s not what I’m about now. That was written about Chris and I’m over it.’

All of Amy’s songs were about her experiences and by this time Chris was firmly in the past. With him no longer relevant to her life, that made the songs about him even less relevant.

She’d started writing a lot of new material, and there could easily have been an album between Frank and Back to Black – there were certainly enough songs. But Amy didn’t want to bring out an album unless the songs had a personal meaning to her, and the ones she’d written after Frank and before Back to Black didn’t do it for her. She resisted the pressure from 19 to head back into the studio.

Amy and I often talked about her song writing. I asked her if she could write songs the way Cole Porter or Irving Berlin did. Those guys were ‘guns for hire’ when it came to churning out great songs. Irving Berlin could get up in the morning, look out of the window and ten minutes later he’d have written ‘Isn’t This A Lovely Day?’. ‘Could you do that?’ I’d ask Amy.

‘Of course I could, Dad. But I don’t want to. All of my songs are autobiographical. They have to mean something to me.’

It was precisely because her songs were dragged up out of her soul that they were so powerful and passionate. The ones that went into Back to Black were about the deepest of emotions. And she went through hell to make it.