Читать книгу Amy, My Daughter - Mitch Winehouse - Страница 13

Оглавление5 A PAIN IN SPAIN

During the summer of 2004, in the midst of her first taste of success, Amy’s regular drinking habits were worrying me – so many of her stories revolved around something happening to her while she was having a drink. Just how much, I never knew. On one occasion, she had drunk so much that she fell, banged her head and had to go to hospital. Her friend Lauren brought her from the hospital to my house in Kent and they stayed for three or four days. After they arrived, Amy went straight to sleep in her room and I called Nick Godwyn and Nick Shymansky. They came over immediately and we sat down to discuss what they were referring to as ‘Amy’s drinking problem’.

We had a sense that Amy was using alcohol to loosen up before her gigs, but the others thought it was playing a more frequent role in her life. The subject of rehab came up – the first time that anyone had mentioned it. I was against it. I thought she’d just had one too many this time, and rehab seemed an overreaction.

‘I think she’s fine,’ I told everyone, which she later turned into a line in ‘Rehab’.

As we carried on talking, though, I saw the other side – that if she dealt with the problem now, it would be gone. Lauren and the two Nicks had seen her out drinking, and they, with Jane, were in favour of trying rehab, so I shut up.

After a while, Amy came down, and we told her what we’d been discussing. As you’d expect, she said, ‘I ain’t going,’ so we all had a go at changing her mind, first the two Nicks, then Lauren, then Jane and I. Eventually Jane took Amy into the kitchen and gave her a good talking-to. I don’t know exactly what was said but Amy came out and said, ‘All right, I’ll give it a go.’

The next day she packed a bag and the Nicks took her to a rehab facility in Surrey, just outside London. We thought she was going for a week, but three hours later she was back.

‘What happened?’ I asked.

‘Dad, all the counsellor wanted to do was talk about himself,’ she said. ‘I haven’t got time to sit there listening to that rubbish. I’ll deal with this my own way.’

The two Nicks, who had driven her home, were still trying to persuade her to go back, but she wasn’t having any of it. Amy had made her mind up and that was that.

Initially I agreed with her, since I hadn’t been totally convinced she needed to go in the first place. Later it came out that the clinic had told Amy she needed to be there for at least two months – I think that was what had made her leave. She might have stuck it for a week, but a couple of months? No chance. For Amy, being in control was vital and she wouldn’t allow someone else to take over. She’d been like that since she was very young; it had been Amy, after all, who’d put in the application to Sylvia Young, Amy who’d got the singing gig with the National Youth Jazz Orchestra, and Amy who’d got the job at WENN. She’d had help, yes, but she’d done it – not Janis, not me.

Amy headed to the kitchen. ‘Who wants a drink?’ she called over her shoulder. ‘I’m making tea.’

* * *

Frank sold more than 300,000 copies in the UK when it was first released, going platinum within a matter of weeks. Based on sales, you would have thought Amy’s career was in the ascendant, but that wasn’t the case.

By the end of 2004 there wasn’t much work coming in and I was beginning to think it was all over as quickly as it had started, although Amy wasn’t worried and continued being out there and having a good time. The people around her seemed unaware that nothing was happening with her career and carried on treating her as if she was a big star. I guess if enough people tell you you’re a big star, you come to believe it.

Only my mother could bring Amy back to earth. She didn’t often have a go at her but when she did it was relentless. We were at her flat one Friday night when she told Amy, ‘Get in there. If they’re finished, get everyone’s plates, bring them into the kitchen and do the washing-up.’ Amy wasn’t happy about that, but when everyone else had left, Mum called Amy to her again: ‘Come here, you, I want to talk to you.’

‘No, Nan, no.’ Amy knew what was coming. She had said something earlier that my mum had considered out of line.

‘Never let me hear you say that again. Who do you think you are?’

It did the trick. My mother was a stabilizing influence on Amy and made sure her feet were firmly on the ground. So, it was no surprise that it hit Amy hard when her grandmother fell ill in the winter of 2004. I drove round to Amy’s, dreading the moment when I had to say, ‘Nan’s been diagnosed with lung cancer.’ When Amy opened the front door of her flat I choked out the words before we fell into each other’s arms, sobbing.

Alex moved into my mum’s flat in Barnet for a couple of months to be with her, and when he moved out Jane and I took his place. We wanted to make sure she was never on her own because there had been a mix-up with one of my mum’s prescriptions: she had inadvertently been taking ten times the correct dose of one particular drug. It had spaced her out to such an extent that we thought the cancer must have spread to her brain. Once we discovered the mistake and rectified it, she was back to normal within a couple of days.

All of the things that you would normally associate with lung cancer didn’t apply in my mum’s case. She was a bit breathless so she had an oxygen machine, but other than that she was very comfortable. During the last three months of her life she actually improved – well, outwardly she did. Then one evening in May 2006 I came home to find her on the floor. She’d had a fall. She didn’t appear too bad, but I called the paramedics just to be on the safe side. They took her to Barnet General Hospital, and while they were checking her over there, she looked at me and said, ‘That’s it. I’ve had enough.’

I asked what she meant.

‘I’ve had enough,’ she said.

I told her not to be silly, that after a good night’s sleep she’d feel better and I’d be taking her home the following day.

‘I’ve had enough,’ she repeated. And those were the last words my mother ever spoke to me. That night she fell into a coma and a day and a half later she passed away peacefully.

I felt awful because my mother had asked me to stay with her, and once she was asleep I’d gone home for a couple of hours’ rest.

‘Don’t be silly, Dad,’ Amy said. ‘She was in a coma.’

My mother’s death had an enormous impact on Amy and Alex. Alex went into a state of depression and withdrew into himself, and Amy was unusually quiet. But the depth of Amy’s sorrow didn’t surprise me. Five days after my mum died my friend Phil’s sister Hilary got married for the first time, aged sixty, to a lovely guy called Claudio. Although we were in mourning, we felt we should go to the wedding. Jane, Amy and I went, but Alex couldn’t face it. Weeks before the wedding Amy and I had been asked to sing at the reception. My wedding present to them was a pianist. I’d worked with him before so I didn’t need to rehearse with him. That night I got up and sang. It was only a few days after my mum had passed away so it was difficult, but I managed it.

Then Amy got up to sing and just couldn’t. She couldn’t sing in front of the guests, she was too upset. Instead, she went into another room with the microphone, so the guests couldn’t see her, and sang a few songs from there. Although she sounded fantastic, I could hear the pain in her voice.

‘Dad, I don’t know how you could get up in front of all those people and sing,’ she said to me afterwards. ‘You’ve got balls of brass!’

I’ve always been able to put my emotions to one side, but Amy couldn’t. She loved singing, but I’ve never felt that she really loved performing.

* * *

After Frank came out, Amy would begin a performance at a gig by walking onstage, clapping and chanting, ‘Class-A drugs are for mugs. Class-A drugs are for mugs …’

She’d get the whole audience to join in until they’d all be clapping and chanting as she launched into her first number. Although Amy was smoking cannabis, she had always been totally against class-A drugs. Blake Fielder-Civil changed that.

Amy first met him early in 2005 at the Good Mixer pub in Camden. None of Amy’s friends that I’ve spoken to over the years can remember exactly what led to this meeting. But after that encounter she talked about him a lot.

‘When am I going to meet him, darling?’ I asked.

Amy was evasive, which was probably, I learned later, because Blake was in a relationship. Amy knew about this, so initially you could say that Amy was ‘the other woman’. And although she knew that he was seeing someone else, it was only about a month after they’d met that she had his name tattooed over her left breast. It was clear that she loved him – that they loved each other – but it was also clear that Blake had his problems. It was a stormy relationship from the start.

A few weeks after they’d met, Blake told Amy that he’d finished with the other girl, and Amy, who never did anything by halves, was now fully obsessed with him.

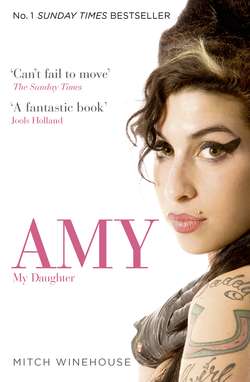

A couple of months later I saw Blake for the first time, although I didn’t actually meet him then, at the Queen’s Arms, in Primrose Hill, north-west London, where I’d arranged to meet Amy one Sunday lunchtime. I walked into the busy pub and saw her sitting on some fella’s lap. They were kissing passionately. The pub was packed and I thought, This isn’t on. I got hold of her, took her outside and gave her a piece of my mind – she shouldn’t have been doing that in a public place. We had a bit of a row and Amy told me she had been kissing her boyfriend, Blake. I said I didn’t care who he was, and I was about to walk off when I stopped and turned round. ‘And another thing,’ I said. ‘What’s with all the big hair and the makeup? Who are you meant to be?’

‘Don’t you like it, Dad? It’s my new look.’

I thought she’d looked nicer when she was a bit smarter, though I had to admit the look suited her, but I didn’t say so then.

‘Come on, Dad, come and have a drink with us,’ she said.

I was still seething so I made some excuse. It was none of my business where and whom my twenty-one-year-old daughter kissed but I’ve always been a bit hot-headed, especially where my kids are concerned.

* * *

Amy’s old friend Tyler James says that he noticed a massive change in Amy when she first met Blake. To Tyler, the day Amy met Blake, she fell in love with him, and after that they wouldn’t leave each other’s side. He became the centre of Amy’s world and everything revolved around him. Tyler told me that the first time Blake visited Amy’s flat at Jeffrey’s Place, he offered Tyler a line of cocaine while they were watching TV – not something that Tyler or Amy would normally have come across. Amy was, as I said, dead against class-A ‘chemical’ drugs, as she called them, and while Blake was doing cocaine, Amy stuck to smoking cannabis (which led to her lyrics on ‘Back to Black’, ‘you love blow and I love puff’). And she was still drinking.

I found out later that Blake had been dabbling in heroin when Amy had first met him. Tyler, who was staying at the Jeffrey’s Place flat at the time, would wake up in the morning and throw up because of passive heroin intake but he didn’t know for sure that Blake was a user until Amy told him.

Tyler wasn’t the only one who saw a change in Amy. Nick Shymansky remembers a pivotal moment around this time when he called Amy from a ski trip. She sounded ‘really different’. ‘I’ve just met this guy,’ she told Nick. ‘You’ll really love him. He’s called Blake and we’ve fallen madly in love.’

Nick came back from his trip and saw immediately that Amy must have lost a stone and a half in weight while he had been away. She started phoning him in the early hours of the morning when she was drunk. One night she called saying she had had a row with Blake and was in a pub in Camden and wanted Nick to pick her up. Nick always felt protective towards Amy so naturally he went to collect her. This was the first time since Chris that Amy had been in love and, according to Nick, it was a terrible two or three weeks. Everyone was worried about her and they all knew something was up.

Amy and Blake’s turbulent relationship only got worse. As if the drug use wasn’t bad enough, Amy soon found out that Blake was cheating on her with his old girlfriend, a discovery that culminated in the first of their many splits. According to Tyler, Amy ended the relationship because of the heroin and the other woman. Until then, Amy and Blake had been together every day, and then they simply weren’t.

She took the break-up hard. Not long afterwards, Amy and I were walking on Primrose Hill – she loved our walks there and, back then, few people recognized her so we weren’t mobbed by fans. That afternoon I could tell she was miserable.

‘You know, I really want to be with him, Dad, but I can’t,’ she told me. ‘Not while he’s still seeing his ex.’

I didn’t know whether to be encouraging or realistic. After all, I didn’t know anything about Blake at that time. ‘You know what’s best, darling. I’ll support whatever decision you make.’

She squeezed my hand. ‘It’s me, isn’t it, Dad? I always pick the wrong boys, don’t I?’

‘Tell you what,’ I said, wanting to do something, anything, to make her feel better. ‘You know Jane and I are off to Spain on holiday? Why not come with us?’ I didn’t think for a moment she’d agree, but I was delighted when she did.

The three of us stayed at Jane’s dad Ted’s place in Alicante. It’s a lovely old farmhouse, secluded, with a pool. We’d all been there before and had a great time. On that trip we’d gone to a nearby jazz café where Amy had stood up and sung with the band. I felt this holiday would give her a chance to forget about Blake and write some more songs without too many interruptions.

The only problem was that she’d forgotten to bring her guitar. We went into the nearby village of Gata de Gorgos and bought her one from a fantastic workshop owned and run by the brothers Paco and Luis Broseta – we were in there for hours. Amy must have tried out a hundred before she settled on a really nice small one, perfect for someone of her size.

When we got home, Amy went to her room to start writing. I could hear her strumming, then pausing to write down the song. She never brought the guitar out of her room to play any of her songs to us, it all went on privately. This went on for quite a while and then there was quiet. After about an hour, I went to her room and she was on the phone to Blake. When she finished the call, she came outside and happily told me that he wanted to get back with her. After that, they were on the phone for hours – and I do mean hours.

Amy was missing the best parts of the holiday, shutting herself away with the phone. Even dinnertime meant nothing to her. ‘Will you come out of your bloody room?’ I said to her. ‘You’re driving us mad.’

So she would leave her room and start walking up and down in the garden – but she’d still be on the phone all the time. It went on and on and on, every day of the holiday.

When we got back to England, Amy and Blake were together for a few weeks until they split up again. And so it began.

It was around that time that Amy met a guy named Alex Clare, and they were together on and off for about a year. Alex was really nice and I got on very well with him. We both loved Jewish food and we’d often go with Amy and Jane to Reubens kosher restaurant in Baker Street in London’s West End to eat together.

Shortly after Amy met Alex he moved in with her and, initially, they were very happy. At one point they even talked about getting married. Amy loved cats and dogs, and not long after Alex moved in, she bought a lovely dog called Freddie, but he was like a raving lunatic. One day Amy and Alex were out with him for a walk and Freddie got lost. ‘He’d probably had enough of me and ran away,’ Amy said. ‘I don’t blame him!’ He was never found.