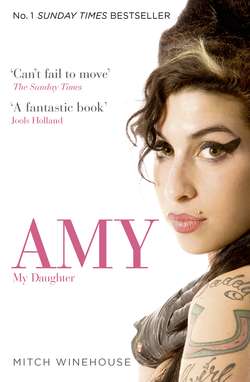

Читать книгу Amy, My Daughter - Mitch Winehouse - Страница 14

Оглавление6 FADE TO BLACK

Looking back on the period between the end of the promotion for Frank and the release of Back to Black, I realize I had no idea of what was about to happen to Amy musically or in her private life. Her habit of writing highly autobiographical songs meant that when she was happy she didn’t turn to her guitar often. There weren’t that many gigs, but she didn’t seem bothered. I began to wonder if there would ever be a second album. I felt she was drifting.

19 were also wondering about the next album. They’d been ready for her to do something as early as 2004, but with her focus elsewhere, there had been little development. Towards the end of 2005, Amy’s contract with them was running out and my impression was that she and 19 were tiring of each other. 19 had set up meetings at restaurants with Nick Gatfield, head of Island Records, and Guy Moot, head of EMI Publishing, and Amy had not shown up. These were big people in the music business, so her no-shows were embarrassing for 19 and they started to lose faith in her.

Amy, in turn, was disappointed that they hadn’t broken her into the US market. And, of course, she hadn’t been happy with the final cut of Frank. When it came time to think about the follow-up, those issues reappeared. Regardless of the problems each side had with the other, the reality was that no money was coming in and I was starting to worry about Amy’s finances. Jane and I went to see her play at a pub in east London where the room was thick with smoke (this was before the smoking ban), and she was paid just £250 (I didn’t know that she was playing as a favour to a friend).

The next day, I told Amy we might have to think about selling the flat unless the money started coming in.

‘Dad, you can’t,’ she said. ‘Don’t worry, I’m going to bring out another album.’

I knew she meant it, but those words had been floating around for so long I was beginning to doubt them. All I knew was that she’d written a few songs when we were in Spain, probably not enough for an album; I didn’t know how many others she’d worked on previously or since. ‘How many songs have you got?’ I asked her.

‘I’m doing it, Dad,’ Amy replied, ‘I’m doing it, so don’t worry about it.’ And that was all she’d say to me. She was never comfortable talking about her writing – especially when she wasn’t doing any.

I wasn’t seeing Amy as regularly as I used to, although I spoke to her on the phone every day. I put this down to her seeming obsession with Blake, and I noticed she mentioned Alex Clare less and less. But she was a grown-up and it was none of my business, so I kept my mouth shut.

When Amy’s management contract with 19 came up for renewal she told Nick Shymansky that she was not sure about carrying on with them. He didn’t know what to say because he felt that she still wanted him in the picture but not 19. Amy had issues with Nick Godwyn on a day-to-day level but Nick Shymansky, by his own admission, didn’t have enough experience or knowledge to manage her by himself, so he tried to get Amy to work things out with 19.

Around this time Nick took Amy to meet record producer and songwriter Paul O’Duffy. He’d worked with Swing Out Sister and produced the John Barry soundtrack for the James Bond film The Living Daylights. The song he and Amy wrote together was ‘Wake Up Alone’ for Back to Black. I was pleased she was getting down to some work but, of course, she wouldn’t play me the song.

In the car driving back from Paul’s house, Amy said that if Nick wouldn’t leave 19 and manage her, then Blake and his mates would take over. Naturally there was no way Nick would allow that to happen – on a few occasions he’d had to pull her out of the pub when she’d been with Blake and his pals to go to meetings. When Nick heard about it he went mad and the two of them got into a huge argument that ended with him telling Amy that, whatever happened, Blake and his mates would not be managing her.

It was then that Nick raised the possibility of Raye Cosbert managing her. Raye was already promoting some of Amy’s gigs and she had built up a great relationship with him. Everyone at Island knew and liked Raye too. Amy had known Raye since 2003 and I knew that she liked and trusted him. Importantly, he and Amy shared similar tastes in music.

I’d first heard of Raye in the middle of 2005 when I’d gone to Amy’s dressing room after a show and found a bottle of champagne from him. I asked Amy who he was and she told me it was Raye Cosbert of Metropolis Music, who’d been promoting a lot of her gigs. I’d seen a big black guy with dreadlocks hanging around the gigs quite a bit and now I realized he must have been Raye.

One night I introduced myself to him and we got chatting. He told me that, apart from seeing me at some of Amy’s gigs, I was vaguely familiar. ‘Do you go to the football?’ he asked.

‘I’m a season ticket holder at White Hart Lane,’ I said. He was too.

Then he asked me to turn round with my back to him – I thought he was mad, but I did it anyway.

‘That’s it!’ he said. ‘I recognize the back of your head!’

It turned out that my seat was four rows in front of his, just to the left. We’re both ardent Spurs fans so we had an immediate rapport. After that we became great friends and always found each other at half-time to have a catch-up.

Once Nick had suggested Raye as a possible manager, Amy, Raye and I had a dinner meeting at the Lock Tavern, a gastro pub in Camden Town, to talk about Amy’s management and discuss Raye’s experience. I was concerned because I knew him as a promoter, but Amy assured me he was right for her. It was raining that night and Amy came in late, as usual. She arrived wearing a borrowed coat and I suggested she buy one like it because it suited her. She was wearing a dress, her hair was long, and she looked beautiful, smart and stylish.

‘Hello, darling. You look lovely tonight,’ I told her.

‘Aaaah, Dad, thanks.’ She beamed at me.

She seemed a bit tipsy so I made a point of not refilling her glass as quickly as she emptied it.

Over dinner Raye outlined his plans for Amy. He impressed us with his forward-thinking ideas, saying that she needed to move on. He suggested it was time to break her in America, and take her to number one there as well as in the UK. He also pushed the idea of a new album and more gigs: if we did this right we were definitely going to crack it. I didn’t know it at the time but Amy had already played him some of her new songs and he thought they were fantastic.

Raye speculated that 19 probably felt that doing a second album with Amy might be difficult as Amy wasn’t happy with the final cut of Frank. They didn’t want her to leave them but he thought they wouldn’t stand in her way if she decided to go.

After everything Amy and I had heard from Raye, we decided she should sign a management deal with Metropolis. We’d made some marvellous friends at 19, some of whom remained her friends, but it was time for a change. (Amy always accumulated friends rather than dropping them.) 19 had done some great things for her: without them she probably wouldn’t have got record and publishing deals, but I think they probably felt they had taken her as far as they could. When it came down to it, I was reminded of Amy’s schools: they were quite pleased to see her go.

* * *

Leaving 19 was a tough decision but it turned out to be the right one. In the end, Amy’s relationship with Raye Cosbert and Metropolis became, in my view, one of the most successful artist/manager partnerings in the music business.

Very quickly, Raye set up meetings with Lucian Grainge at Universal, and Guy Moot at EMI. Raye’s energy was just what Amy’s career needed – like a kick up the arse. For some time Guy Moot had wanted Amy to get together with the talented young Mark Ronson, a producer/arranger/songwriter/DJ. In March 2006, a few months after she’d signed with Metropolis, Raye encouraged her to meet Mark in New York so the two of them could ‘hook up’. She knew very little about him before she walked into his studio on Mercer Street in Greenwich Village, and on first seeing him, she said, ‘Oh, the engineer’s here.’ Later she told him that she’d thought he would be an older Jewish guy with a big beard.

That meeting was a bit like an awkward first date. Amy played Mark some Shangri-Las tracks, which had the real retro sound that she was into, and she told him that was the sort of music she wanted to make for the new album. Mark knew some of the tracks Amy mentioned but otherwise she gave him a crash course in sixties jukebox, girl-group pop music. She’d done the same for me when I’d stumbled over a pile of old vinyl records – the Ronettes, the Chiffons, the Crystals – that she’d bought from a stall in Camden Market. That had been where she’d developed her love of sixties makeup and the beehive hairdo.

They met again the following day, by which time Mark had come up with a piano riff that became the verse chords to ‘Back to Black’. Behind the piano, he put a kick drum, a tambourine and ‘tons of reverb’. Amy loved it, and it was the first song she recorded for the new album.

Amy was supposed to be flying home a few days later, but she was so taken with Mark that she called me to say she was going to stay in New York to carry on working with him. Her trip lasted another two weeks and proved very fruitful, with Amy and Mark fleshing out five or six songs. Amy would play Mark a song on her guitar, write the chords down for him and leave him to work out the arrangements.

A lot of her songs were to do with Blake, which did not escape Mark’s attention. She told Mark that writing songs about him was cathartic and that ‘Back to Black’ summed up what had happened when their relationship had ended: Blake had gone back to his ex and Amy to black, or drinking and hard times. It was some of her most inspired writing because, for better or worse, she’d lived it.

Mark and Amy inspired each other musically, each bringing out fresh ideas in the other. One day they decided to take a quick stroll around the neighbourhood because Amy wanted to buy Alex Clare a present. On the way back Amy began telling Mark about being with Blake, then not being with Blake and being with Alex instead. She told him about the time at my house after she’d been in hospital when everyone had been going on at her about her drinking. ‘You know they tried to make me go to rehab, and I told them, no, no, no.’

‘That’s quite gimmicky,’ Mark replied. ‘It sounds hooky. You should go back to the studio and we should turn that into a song.’

Of course, Amy had written that line in one of her books ages ago. She’d told me before she was planning to write a song about what had happened that day, but that was the moment ‘Rehab’ came to life.

Amy had also been working on a tune for the ‘hook’, but when she played it to Mark later that day it started out as a slow blues shuffle – it was like a twelve-bar blues progression. Mark suggested that she should think about doing a sixties girl-group sound, as she liked them so much. He also thought it would be fun to put in the Beatles-style E minor and A minor chords, which would give it a jangly feel. Amy was unaccustomed to this style – most of the songs she was writing were based around jazz chords – but it worked and that day she wrote ‘Rehab’ in just three hours.

If you had sat Amy down with a pen and paper every day, she wouldn’t have written a song. But every now and then, something or someone turned the light on in her head and she wrote something brilliant. During that time it happened over and over again.

The sessions in the studio became very intense and tiring, especially for Mark, who would sometimes work a double shift and then fall asleep. He would wake up with his head in Amy’s lap and she would be stroking his hair, as if he was a four-year-old. Mark was a few years older than Amy, but he told me he found her very motherly and kind.

This was a very productive period for Amy. She’d already written ‘Wake Up Alone’, ‘Love Is A Losing Game’ and ‘You Know I’m No Good’ when we were on holiday in Spain, so the new album was taking shape. Before she’d met Mark, Amy had been in Miami, working with Salaam Remi on a few tracks. Her unexpected burst of creativity in New York prompted her to call him. She told him how excited she was about what she was doing with Mark, and Salaam was very encouraging. Jokingly, she said to him, ‘So you’d better step up.’ Later she went back to Miami to work some more with Salaam, who did a fantastic job on the tracks he produced for the album.

When Amy returned to London she told me excitedly about some of the Hispanic women she’d seen in Miami, and how she wanted to blend their look – thick eyebrows, heavy eye-liner, bright red lipstick – with her passion for the sixties ‘beehive’.

By then, Mark had all he needed to cut the music tracks with the band, the Dap-Kings, at the Daptone Recording Studios in Brooklyn.

Shortly after that my mother passed away and Amy, along with the rest of the family, was in pieces. It wasn’t until a few weeks later, in June 2006, that Amy added the last touches to ‘Back to Black’, recording the vocals at the Power House Studios in west London.

I went along that day to see her at work – the first time I’d been with her while she was recording. I hadn’t heard anything that she’d been doing for the new album, so it was amazing to listen to it for the first time. The sound was so clear and so basic: they’d stripped everything back to produce something so like the records of the early sixties. Amy did the vocals for ‘Back to Black’ over the already-recorded band tracks, and I stood in the booth with Raye, Salaam and one or two others while she sang.

It was fascinating to watch her: she was very much in control, and she was a perfectionist, redoing phrases and even words to the nth degree. When she wanted to listen to what she’d sung, she’d get them to put it on a CD, then play it in my taxi outside, because she wanted to know how most people would hear her music, which would not be through professional studio systems. In the end, Back to Black was made in just five months.

Amy’s CD sleeve for the Back to Black sampler. Amy still loved her heart symbol and drew a good self-portrait. She still seemed a schoolgirl at heart.

The album astonished me. I knew my daughter was good, but this sounded like something on another level. Raye carried on telling us that it would be a huge hit all around the world, and I was getting very excited. It was hard to read Amy: I couldn’t tell if she expected it to be a triumph, as Raye did, but she was much happier with the final cut than she had been with Frank. This had been a much more hands-on process for her.

Back to Black was released in the UK on 27 October 2006, and during its first two weeks it sold more than 70,000 copies. It reached number one on the UK Albums Chart in the week ending 20 January 2007. On 14 December 2007 it was certified six times platinum in the UK in recognition of more than 1.8 million copies sold. By December 2011 Back to Black had sold 3.5 million copies in the UK and more than 20 million copies worldwide.