Читать книгу Clown Girl - Monica Drake - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5.

Plucky, Come Home!

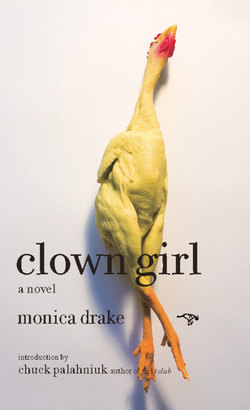

IN THE BACK OF REX’S PROP-ROOM AMBULANCE, I GATHERED pens and paper and made a sign: Missing: Rubber Chicken. I sketched the chicken’s long rubber neck, her fallen-over comb, dangling legs, and splayed toes. I inked in the black lines of a heart on her chest, her defining characteristic, like a birthmark or a scar.

The ambulance’s two back doors hung open to let a breeze in. Outside a mechanical xylophone blasted the hard notes of “Home on the Range,” as One-Night Stan the Ice- Cream Man trawled nearby. I perched on a pile of costumes with the shades pulled, wearing a sun hat with a big brim and a cluster of silk flowers in front. The only thing wrong with the hat was two holes cut in the top meant to accommodate rabbit ears back when the hat was part of a show.

Below the rubber chicken picture, on my sign, I wrote, Name: Plucky. Height: 15”. Value: Sentimental. Then I wrote: Reward: $$$.

I tore off the part about a reward. What could I offer? If the rubber-chicken thief were a King’s Row kid, my reward would be a bad joke next to the punk’s allowance. I crunched the scrap in my hand.

But I wanted Plucky back. Plucky belonged with Rex and me. We’d had good times together. I wrote it again, in the space that was left: Reward. Then crossed it off. I couldn’t give money away.

But who would return a rubber chicken without incentive? Plucky would end up tossed in an entryway, left in a backyard, or given to charity. I wrote it one more time, above the black cross-off mark: Reward, followed by only one dollar sign. I’d pay for that chicken’s safe return because she was mine, ours, the first and now the only child of our union, the memento of sex, evidence of sex, Rex Galore.

Rex and me, our second date wasn’t a date so much as it was a show. He invited me for a night onstage. We were juggling together, pins in the air, moving hand to hand with a good rhythm going, when he invited me to work with him, to be a moving table, a prop stand in his fire-juggling act. Put fire in the show, audiences love it. That’s what Rex always said: Burn shit up. I was wary. It was so much, so soon, I said, “You don’t think we’re rushing things?”

He said, “I’m ready.”

With the way the pins spun smoothly between us, six in the air, I knew I was ready too. I saw my future: if the date were an audition, I’d nail it.

The night of his show I wore a legless tabletop strapped to my back, in a nightclub, and underneath that board I swayed to Rex’s dance. The crowd was sauced. Somebody yelled, “Prestidigiate!” An empty plastic pitcher flew onto the stage. The pitcher spun, beer speckled my face, and I laughed out loud. The energy was nothing like the hollow garages of art gigs, the scream of birthday parties, or the dead air in the corporate scene.

Rex rapped on my tabletop and the sound amplified in my ears. Rex was amplified, bigger than life, his name chanted by strangers, his soundtrack a crazy mess of Ska, tribal, and Cambodian pop. His feet were bare and strong, legs muscled. That was all I could see from down low. His hands hit the floor between his feet and his legs scissored up and out of view. His curly hair dropped to the stage, damp with sweat. Dionysus, Pan. Bacchus, Shazam. My Wonder Twin. He was a god, a gymnast, a laugh riot, a dream.

Rex piled bottles on the table of my back. He balanced fire wands on the bottles and the flames reflected in mirrors at the edges of the stage. I was in the middle of a bonfire, a forest fire, a burning building. Magic. Everyone looked at the flaming pyramid of bottles on my back. My knees rubbed hard against the uneven floor of the stage. Rex rode a unicycle. His single wheel circled as I shuffled.

If Rex asked me to eat glass, I would’ve done it.

Later, in the quiet of the dressing room, he closed the door. I stood. My legs trembled, knees stiff with exertion, exhilaration, and nerves. Rex said, “You’re a natural.” He unstrapped the table, lifted it from my back, and set it aside.

“It was all you,” I said.

“Not at all!” His big hands reached forward to massage my shoulders. I closed my eyes and groaned. “Tough work, isn’t it?” He let his hands slide down my shoulders to the collar of my black catsuit, lowered the zipper in back. The cloth peeled away, cool air brushed my skin and my shoulders stretched larger, free of the fabric. “Goosebumps,” Rex said and ran a finger down my spine, his voice a quiet growl. His skin smelled hot, flammable as white gas. He touched a calloused finger to my collarbone, then ran his finger down over my breast and pushed the suit lower. Bottles rolled over the floor between smoking batons. Sweat-marked Lycra clung tight as hands against my thighs, my hips.

We dropped onto a sagging couch buried in costumes, and around us the costumes smelled like every show there’d ever been, every date, every human body: smoke, perfume, and cologne layered over the musty mix of Goodwill and basement mildew, cat piss, the hot animal ripeness of nerves and sweat. This was our opening night. Rex was on top of me, his weight and smell, and the clothes underneath us were like a hundred people there, a bed of empty arms and torn pant legs.

My clown makeup smeared across the white spaces of Rex’s clown face and made a print on his skin.

I pushed him back an inch, said, “Your lipstick’s smeared, dahlink.”

When he smiled, his cracked makeup deepened the creases in his face until he was a marionette, a dusty doll, an outdated mannequin.

He leaned forward, bit my belly. With gentle bites he moved along my ribs, up, until he found the white of my breasts, until I was covered in patches of red, smeared chalk white, and blue-black like bruises. Rex Galore and I blended, designs merged and morphed. Forget P.T. Barnum—sex was the greatest show on earth, and Rex and me, we were a tangle and I was lost in the perfume of white gas, smoke, and sweat. I couldn’t breathe. I was buried alive. Did I care? Only for an encore.

Rex undid his fly. The catsuit was a pile of darkness on the floor.

I whispered, “Do you have a rubber?”

He laughed, hushed, a laughing whisper, as though his parents were in the next room, and reached one arm past my head to a nightstand there. “A rubber chicken.” He shook the dancing chicken in the air. “Will that do?”

I laughed back, ran a finger along the bumps of the fake chicken skin. “Ribbed and beaked for her pleasure, even. Want me to leave you two alone?”

He threw the chicken on the floor and bit my neck and I giggled and he said, “Never,” and he was everywhere then. The couch was a sinking place and I disappeared into the orgy of costumes, the smell of nervous strangers, makeup, and smoke, my naked body buried in the perfume of human need.

I took the rubber chicken home. Plucky was my mascot, the souvenir of our date. Later, much later, there was the conception of our child. And now the miscarriage, unexpected, though I should’ve expected it because, why not?—family slid through my fingers the same as the old silicone banana-peel trick. After the D & C, after the suctioning away of our tiny fetus, I drew the black heart on Plucky’s rubber breast in the place where a chicken might have a heart, over the ridges of implied feathers. Indelible ink.

Now she’d been nabbed by a kid too young to know what love means, what a chicken might mean. Too young to know that a rubber chicken can carry all of love in one indelible ink heart.

On my sign, I wrote Missing: One Rubber Chicken, One Lover, One Unborn Child. Missing: my whole life. I tore the ragged sheet in half, picked up another and started again. Swollen Sacred Hearts, shrunken wise men, and bloated angels bobbed at my feet, the fruits of my labor. On the shopworn dedication page of Balloon Tying for Christ it said, “With appreciation and gratitude for my wife and six lovely children who have borne with me through twelve long years of deprivations while completing this work.” Such martyrs! Balloon Tying for Christ was maybe all of seventeen pages long, with one blank page at the end. The tricks inside, by corporate accounting, were worth hundreds of dollars. Matey, Crack, and me, that’s what we earned when high-end work came in. But work didn’t always come. We had to promote, and deliver. That book was my cash cow.

One-Night Stan’s ice-cream truck, the neighborhood drug mobile, still played nearby. Drugs, ice cream, balloon toys and prayer—these are the things you sell when there’s nothing else left.

Over the sound of the ice-cream song, a loud rattle out in the street grew louder. I looked out the ambulance’s back doors. There was a man down the block walking a loping shuffle to the music of his own loose-wheeled lawn mower. I pulled a green balloon from my pocket. In Herman’s yard, Chance circled, dazed and restless. Sunlight rippled on her fur. I blew up the balloon with a new kind of dizziness after the hospital, and tied a knot at the stem too soon, leaving a long stretch of uninflated balloon tail. I twisted one section for a head to make Jesus-on-the-Cross in Easter green, massaged the rubber to minimize the tail, and twisted dangling balloon legs into place.

Just as I found my focus, concentrated on my work, there was a rap against the ambulance. I jumped, startled, and knocked my hat half-off. A man grinned in at me. The man with the lawn mower. “Patient going to make it, Doc?” He was missing two front teeth. I tipped my sun hat back to look at him. He wore a tank top, dripped sweat, and had that red turkey neck from being out in the sun too long. Chance ate grass at the side of the road, eyes on the man. His lawn mower was rusted.

“What’s up?” I said, and stretched a new balloon.

“I’m good, I’m quick, I’ll do the whole lawn, front and back, for eight bucks.” He raised his voice to talk over the ice-cream truck’s song.

We eyed each other through the open back doors. I didn’t mind the grass long; it had a richness to it. A ribbon of tiny white flowers bloomed along a sunken channel where water, or maybe sewer, ran below. Speck-sized insects swarmed above the weeds like a burst of tiny bubbles. I tipped my sun hat down again. The silk flowers made the light scritch-scratch of tiny toenails against the straw like the mice that roamed Herman’s kitchen drawers.

“What makes you think I live in that house?” I said.

“Oh, I seen you’round. You’re the clown girl. I seen you out here in the overgrowed grass, with your little dog and that hula hoop you got.”

I moved in my own newly slowed time, behind the buzz in my head, my after-hospital pace. The sky, through my sunglasses, was a cherry-tinted blue. I took out a yellow balloon for the cross. Gave it a snap, blew it up. The man had a boil on his lip that was lighter than his skin, a swollen flash of white. He said, “What is that ‘Baloneyville Coop’ anyways?” He pointed at the wooden sign over Herman’s door.

I tied the knot at the end of the balloon. “It’s a Co-op,” I said. “There’s a space break in there.”

He let his head bounce in a nod, then said, “OK, whatever. That’s y’all’s business. Mine is mowin’, and I’d say your coop needs a little trim.” He laughed, like it was some kind of big joke. But he was right. Herman only had a push mower, a rusted reel of dull blade. Our backyard was as overgrown and choked as the front, with an aging apple tree in the center and a blackberry thicket along the fence line. It’d been my turn to mow Herman’s lawn for weeks—I was the bottleneck, the hold up. The grass grew longer every day. After the hospital, I needed to rest.

“Everybody needs a little trim, now and again,” the lawn mower man said with a grin.

I could pay this man to do my work, or pay for the return of Plucky. One or the other. I said, “I don’t own the house. Can’t hire you without asking.” I doubled the yellow balloon over, twisted the green Jesus around it.

The man drank from a plastic cup carried in a cup holder taped to the lawn mower’s handle. He ran a hand over his sweaty face. “OK, seven bucks. Can’t go lower,” he said.

Baloneytown was the neighborhood dealers, hookers, scamsters, and gangbangers came home to. It was where they grew up. Every corner was marked with a brick wall broken by a driver too strung out, trashed, or craving to stay on the road. Half the houses were red-tagged—windows plastered with red Condemned stickers—and the red-tagged houses were still lived in. You couldn’t trust anybody.

I picked up Balloon Tying for Christ and slid off the pile of clothes and out of the sauna of an ambulance. Costumes clung to my legs, a sea of velvet, satin, and Lycra. Standing up fast in the heat meant more of the swimming in my head, the warm hum of bees swarming, the blood resting around my lungs, around my stomach, nowhere near my brain. I saw a flash of blue against the inside of my eyes, felt faint, and caught the side of the ambulance for balance. I pressed my wrist against a cool, shaded bit of steel.

BALLOON JESUS BOBBED IN THE ROAD, ADRIFT ON HIS cross. In my dizziness, Jesus was a million miles away and still at my feet, a supplicant. My feet were miles away. I pressed my wrist to a new spot of shaded metal, hoping for anything cool.

In the middle of a wrist’s suicide slash-line, below the layered skin and above the pulse, there’s an acupuncture point that says, Get back to who you were meant to be. This is the heart spot, the center. Your whole life the skin on that place will stay closest to being a baby’s skin, as close as you can get anymore to the way you started, the way you once thought you’d always be. I pressed my baby-heart-spot center into the shaded metal’s coolness, the pulse in my wrist talking to my whole body, to the hum in my head and the blue behind my eyes, saying don’t faint now.

The lawn mower man wiped his face with one sweaty arm. He said, “I do the lawn next door, and done this one, last time with a push mower. Now I got my own. Got an edger now too, and can come back with that tomorrow. I charge three bucks to edge her. Ten bucks total.”

I’d never seen him do anybody’s lawn, but when he said he did our lawn with a push mower that sounded about right. Whose turn was that? Herman’s? I bent for the fallen balloon Jesus. Lofted him, cross and all, into the ambulance.

“My old lady’s at Bess Kaiser Hospital. We need money to have a carbuncle lanced off her breast.” He ran his tongue over the boil, then patted his pockets like he was looking for a business card.

A cop car turned the corner, came our way. Quick as Keno, Mr. Lawn Mower took his loping stride off to somewhere behind the ambulance. I bent, looked in the cop car window, and caught a glimpse of light hair cut short, the blue uniform. My heart knocked, lurched. Was it my cop—and when did he become my cop? The cop with my urine funnel. With no time to hide—I held my big straw hat in front of my face and looked through the rabbit-ear holes in the hat’s crown.

It wasn’t my cop. It was somebody younger, weasel-faced. Nobody. The nobody cop gave a thumbs-up and a smirk, then passed on by. Only then did my blood start to move again, heart still beating.

The lawn mower man came out to collect his mower. Maybe I gave something away, a shift in my face, a green tinge of guilt, because to me, joking or not, he said, “That cop looking for you, Clown Girl?” Ha! It didn’t come across as a joke. We were each in our own private cold sweat. That’s the problem—a cop is a loaded question. Let one cop in, and the rest of the picture is a whole new story.

AT HERMAN’S, I TRIED TO CALL REX AGAIN FROM THE phone in the kitchen. Italia stopped licking peanut butter off a knife long enough to say, “Herman wants to know when you’re going to get on with your chores.” Her skirt barely covered her ass. She dropped the knife in the sink.

“He asked you to ask me, or what?” I said.

“Look, Herman can be an easy touch, and you’re a sad case. But that yard’s gone to weeds waiting for you to make a move.”

With one ear to the phone, I put a finger to my other ear.

“You heard me, clown.” She looked in the fridge and showed me her back, that cascade of ink, the geisha and blue waterfall. It looked as though a smaller, more demure woman in a tiny landscape stood in our kitchen.

I picked up a dead fly from the windowsill. When Italia’s back was turned, I floated the fly on her coffee. The oldest joke in the book: Waiter, what’s this fly doing in my soup? Looks like the backstroke, Miss. Nyah, nyah, nyah.

I took the phone to my room and called again. The machine picked up: “Yello, yello, yello! We’re off to the races, kiddos…” I lay on our mattress while the sun dropped lower outside my backyard windows, and I said an incantation: Call me, call me, call me.

The third time I called, a man answered. He didn’t sound like a clown. There was no fun in the rasp of his voice. “Ain’t here,” the man said. “He’s out.”

Rex was always out. “Could you ask him to call Nita?”

“Will do.” Before I could get in another word, with a click the line went dead.

Then I heard Italia sputter and cough in the other room. “Jesus Christ. Clown Girl!” She kicked my bedroom door open with one muscled leg. A canvas of Rex fell from where it leaned against the wall and hit the ground with a smack. I started coloring on the Missing Rubber Chicken poster again, fast.

“What?”

She said, “Don’t mess with my food.”

I said it again, “What? I didn’t do anything.”

She even had knotted muscles in her face, her cheeks. She said, “Look—mess with my food, and I’ll kill you. No joke.”