Читать книгу Clown Girl - Monica Drake - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление6.

We’re All Chaplin Here

“IT’S FOR YOU, NITA,” HERMAN CALLED.

Ta da! Rex! It was about time. I ran for the phone; my bare feet slapped against the worn floorboards of Herman’s old house. “At last,” I said, breathless, into the receiver.

“Now that’s a reception,” Crack coughed back, her voice in my ear. “Listen up. I’ve got a chief gig, a big check here. They want the three of us. A package deal, see? If one falls through, we’re all sunk. So go to Goodwill, get yourself an undersized suit coat—smallest one you can get your bones in—and a pair of baggy pants. Black. They’ve got a pile of’em. Meet us in the lobby of the Chesterfield, 6:30 tonight. Got it?”

“Got it,” I said.

She said, “What’s a matter? I hook you up with a sweet deal, you sound like I stepped in your birthday puddin’.”

I said, “No, no, I’m glad. I just thought…”

“Ah, you’re missing your man, is that it?” Her voice was a finger jabbing me in the ribs. “Well, the bigger the dog, the longer the leash. Let him roam,” she said. “Listen, here’s the lemonade to the story, right? With Rex out of the way, we can run this town. Take over the whole King’s Row. By the time you see his mug again, we’ll be flashing the cash. He’ll love you for that, see?”

Right. I said, “Thank you. Thanks for bringing me along.” Before I met Crack, I advertised with an index card on a corkboard at the old Pawn and Preen, and got maybe one job a month.

“No balloons this time,” Crack said. “No tricks, and no excuses. Leave the chicken, the popgun, and the exploding gum at home.”

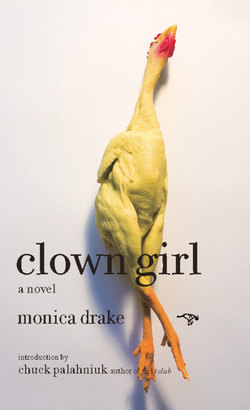

The chicken. Plucky. I wished Plucky were home.

“This is the big bucks, Sweets, the real deal. I’ll set you up with a hat and a cane.”

I said yes to all of it.

I’d been out of the hospital three days, was still on the dizzy side, head buzzing, but could move without feeling faint, could walk at almost normal speed. The orange plastic jug sat empty in my mudroom waiting for a day I could devote to collecting urine. Twenty-four hours of contiguous urine is a tougher trick than it seems. One pee away from the orange jug on ice, and the whole day’s urine file is shot.

ON THE WAY TO THE GIG, I STOPPED AND COPIED MISSING Rubber Chicken posters. The poster had a drawing of Plucky, my name, Herman’s address, and a dancing money sign as promise of a reward. I stapled flyers to phone poles, one eye out for cops, always ready to silly-walk away fast in my oversized wing tips. Posting flyers on phone poles is illegal, but how else to tell the neighborhood?

To keep my chin up, I recited the Clown’s Prayer: “As I stumble through this life…May every pratfall pay the bills. May every tumble lighten strife, all the aches be cured with pills.”

I MET UP WITH CRACK AND MATEY IN A HOTEL LOBBY.

The lobby was wide and lush, with a thicket of plants in the middle. Prom night. Girls dressed like faded flowers lingered with acne-faced dates outside the hotel restaurant. Skinny kids danced through the lobby like they were on vacation, rustling and laughing, calling out names.

Matey, all in black and white, was perched on the back of a couch, feet on the cushions and her cane across her knees. She leaned forward, elbows on the cane. Her shoulder blades stuck up under her white T-shirt like wings over her thin back and took the place of her trademark fake parrot for the night. Crack paced back and forth in front of the couch. She had on a dark wig, a tidy men’s hairpiece, black and shiny as shoe polish.

Matey saw me first, and nodded. “Here she is, Boss.”

Crack looked up. She said, “Christ, could you be any later? When I said 6:30, I meant sharp, like on the dot, like the point on your head, see?” She moved fast and bumped into a short girl dressed like an after-dinner mint, all white with red piping. Crack didn’t look at the girl even after she ran into her.

“What is this?” She pulled the flyers from my hand. “Missing Chicken. Plucky. Aw, real sweet. Now forget about it.” She threw the flyers on the couch and slapped a party-store bowler hat and a bamboo cane against my chest. The hat was made of plastic covered in a thin spray of fuzz like faux felted wool. “Got your suit, sister?”

I had on the big wool pants, and my thighs were sweaty from walking in the summer evening. The air-conditioned hotel was cold as a walk-in fridge. I shivered in my own cooling sweat. I already had on a pair of men’s wing tips, one black, one brown, both size massive. The suit coat was compressed, tight in my shoulder bag. I pulled the coat out of the bag and shook it.

“Right,” Crack said. “Put it on.”

I rested the cane against my leg, pulled on the coat. The shoulders pinched and the sleeves ended half a foot before my arms did.

“Perfect,” Crack said.

The coat had the Goodwill seal of hobo authenticity in mingled cigar smoke and rancid sweat. I could barely move my arms as I collected my flyers, shoved them in the pink bag. If I moved too fast, the coat would rip in two. I said, “All this for a prom gig? That’s a little small-time for what you said. The big bucks.” Prom was teenagers, once a year at best.

“If prom was our gig, I’d shoot myself,” Crack said. “Then again, why shoot myself when I’ve got you two?” She turned on her heel and waved a hand, speaking clown sign language, directing Matey and me to follow.

In the ladies’ room there was a counter of sinks a mile long lined with a mirror on one side and prom girls on the other. Every prom girl was cloned across that counter, all of them in pastels, with big hair and bigger plans. They leaned in close, as though to kiss themselves as they painted their eyes and lips with tiny brushes. The air was a sickening war between the bathroom’s sanitizer and an army of cheap perfume. Crack, in her black suit and white shirt, pushed dresses aside and wedged her way into the line. Prom girls cackled and fluttered, hens in a henhouse.

“Hey,” a hen girl clucked. She had lipstick on her top lip but not yet on the bottom, one bright red lip, the other dry and pale. “You can’t be in here. This is the women’s room.”

Crack tipped her hairpiece. “You must be the housemother, yes?” She grabbed her own boobs through her oversized, rumpled men’s dress shirt. “Want to go over my credentials, cupcake?”

Matey moved in behind the girl, hands flat on her flat chest. She stuck her tongue out to one side and let her eyes roll. “Me next, me next!” She pressed up behind the prom queen.

The girl backed off, wobbly in high heels, and found a place between her friends, body guards in tulle and crepe. Matey and I wedged into the girl’s spot. I tipped my plastic bowler and smiled, clown sign language for Sorry. To say, We’re all friends here.

To Crack I hissed, “What is this, West Side Story? You give these birds reason to hate us.”

Crack said, “Aw, you’re going soft.” She snapped open her hot pink shoulder bag. The shoulder bags were the matching part of our costumes, bought at Ross to look like a team and to hold props while we worked. She poured trays of makeup on the counter, along with triangular sponge applicators, makeup pencils, tampons, a kazoo, and a washcloth. Our makeup came in kits like grade school watercolors. Each color was a small round cake. A paintbrush snapped in place to the side.

Crack spread white makeup on her cheek. She said, “Chaplin. Hop to it,” and she looked at me. “Well, step on it, Sniff. Get your Chaplin on, girl.”

“All of us?” I asked. “So, we’re all the same?”

Matey nodded, twisted sideways and crowded in beside me in the mirror. “We’re all Chaplin.”

I said, “We’re all Chaplin. Bejesus. That’s so redundant. Like three Mickey Mouses in the Macy’s parade, or three promotional Snow Whites at the same video store.”

“Or ten prom queens in the same john,” Matey said, loud. Painted eyes flickered our way and glared in the mirror.

“What’s redundancy got to do with the price of eggs?” Crack said. “Fetishism is the key. Tap into a fetish, we’ll make a fortune, see?” Her face was white now, with no color at all: Lips, white. Eyebrows dusted white. Only her brown eyes, moving fast, were still dark against her face. Her eyes sized me up in the mirror. “If you’re not interested in cash, let me know.” She looked at me in the mirror, then at herself, then at Matey, then at me again. “If you’re keen on small potatoes and Food Fairs, that’s your trip. Fine. I’ll find another clown girl, read me?”

I twisted my hair into a high topknot. “‘Greed has poisoned men’s souls,’” I said, and slid a bobby pin in.

“Hell-o?” Crack said. “Say what?”

“…has goose-stepped us into misery and bloodshed.”

Crack painted on her tiny Chaplin mustache. “Look, I’m not exactly taking it out of your hide. I don’t know what you’re getting at, but I’m here to make a buck…”

I said, “Just quoting Chaplin. I’ve sure you’ve seen The Great Dictator.” I tucked in more hairpins to keep my hair off my face and flat under the bowler.

Matey piped up: “Like, how do you quote a silent flick? Riddle me that one.”

I finished pinning my hair and said, “You’re doing that on purpose, I hope.”

“Don’t count on it,” Crack said. With her tiny mustache and the slick hairpiece, Crack looked halfway to her own dictatorship.

I said, “So, what kind of fetishes are we selling tonight? Chaplin and hairbrush spankings, for the prom crowd?” I pulled my makeup palette from the bag and found a sponge in a plastic Baggie. I ran the sponge under cool tap water. I touched one edge of the sponge to the white cake of base.

Crack said, “Again, Miss High Artiste, it’s not about prom, see? It’s corporate stuff. Call it a logo, branding, whatever they want to call it, but underneath, it’s a fetish. A fetish, by any other name, is still the big bucks.” She closed one eye and used a long paintbrush to circle her eye with black. “Matey knows about fetishes, right, Mate?”

Matey said, “Hey, fetish? Me? Nah, these clothes were fresh this morning.” She bent one foot up, hopped in a circle, and tried to sniff her shoe. Her face was white, her hair pulled back by a dozen tiny bands. She grabbed the counter and swung herself back up to face the mirror, stuck her bowler on her head, and offered a nightmare smile.

“Cover the bruises,” Crack said. She smacked Matey on one bruised forearm. “These corporate yahoos ponied up for their own style fetish, not S&M, you read me? A little wear and tear takes the shine off the illusion.”

Matey dug in her bag and came up with Flesh Tones Cream, shade: sallow. She dropped the tube on the counter. Farther down the wall of mirrors, a prom girl ran a line of silver eye shadow over her eyes, same movements as me and Crack and Matey, different color was all. Crack drew on eyebrows. “They want Chaplin, we’ll be Chaplin, see? If they want their mamas, I say play mama for enough cash. If we give ’em what they want, they’ll find a reason to have us back. High demand, high demand. That’s us. Mark my words, ladies.”

I touched up the white makeup along my chin.

Matey drew a heavy, black, straight line over her thin, arched eyebrows. Her arms were like sticks, her elbows sharp. The white insides of her arms were marked with thumbprint bruises. I wondered if the rumors were true, that Matey was an S&M clown for hire, into the degradation, catering to coulrophiles.

“Juggling pins lately?” I asked, hopeful. Pins caused those kinds of bruises. Sometimes.

Matey glanced at me, didn’t bother to answer. Her makeup cracked around her eyes; her eyes were puffy. I felt a flicker of sadness, but the sadness wasn’t really about Matey. It was bigger than that. I leaned into the mirror, drew on my own lips, and joined every last prom queen in line doing almost the same. We were a sad parade of longing, those lip painters and me, humans trying our hardest. Mostly, I felt the missing life of my tiny baby, my tiny Rexie, who never even made it into this crappy world.

Baby Rexie never had a chance to be a sucker, a chump, a prince, an S&M clown. Whatever he or she might’ve been. And then I thought of my parents, who also died too young, but far older than baby Rex. I was the center, the hinge pin of a family not made to last.

“You guys go to prom?” Matey asked.

One mirror down, a round girl in a baby-blue dress plucked a fine hair from her brow. Her chin already sagged. I could see her as an old lady. How had any of us made it this far?

Crack said, “Prom? Ba! But this one, our Vassar girl, she probably went.”

Me. Vassar? Prom? I shook my head and looked down, away from the mirror. I organized my makeup stack, to give myself a moment.

“Me neither,” Matey said. “I was shooting up, prom night. Learning bad habits.” She knocked on the bathroom counter like knocking on wood for luck.

I said, “Is there luck in Formica?” I gave a knock myself. Blinked damp lashes.

The girl in blue packed up her tiny purse: lipstick, lip liner, eye shadow, perfume, keys, tampons, chewing gum, and little slips of packaged condoms.

Matey said, “Hey, that’s a better trick than clowns in a tiny car. Give us your secret, Cheesecake.”

Crack said, “You must be one-eighth clown, maybe a grand-ma on the Cherokee side? You got the clown nose.” Behind Crack, Matey pretended to squeeze her own nose, as though it were bulbous, and said, “Honk, honk!”

The prom queen took her tiny purse, cut a wide arc around us, and skedaddled toward the door.

We three Chaplins looked back into the mirror. I finished with the thin, pale Chaplin lips, then drew on the famous mustache. Wide eyebrows and a mustache—that’s enough to change a whole face. One clown training manual says, These particular three dots of color alone will divert the eye from the normal visage and render the individual almost unidentifiable.

“I worked as a fry cook prom night. Flat broke. Minimum wage was its own bad habit.”

That made Crack bark out a single-note laugh in appreciation. She liked money jokes. What I didn’t say was that I was already an emancipated minor—emancipated by the state and by an accident on the old California Highway One, before that highway crumbled, where it curved through the redwoods in tight hairpin turns along the edge of the ocean’s rocky cliffs. I ran a circle of black around my eyes and said, “Every real job I ever had, I wore a polyester suit.”

“Shit, don’t I know it,” Crack said. “Either a polyester suit or a thong and platforms.”

None of us worked for minimum wage anymore. As clowns, as long as work came in, we were paid in stacks of twenties. Cash on the spot was Crack’s rule. After another night’s pay, I’d be that much closer to Rex again, that much closer to building, or rebuilding, the family I didn’t have.

Our assignment was to wait huddled in a narrow white hallway, outside some corporate office cocktail party, until we heard the antique stylings of “The Entertainer,” electronically remixed. At least it wasn’t “Send in the Clowns,” impossible to dance to. We dropped our pink bags in a corner.

“When the player piano starts, that’s our cue, see?” Crack said. “Matey, you’ll go first. Bust out your best Chaplin waddle. We’ll be right behind you. One at a time we all fall down, get up, circle back, and exit. Strike fast, no garnish, got it?”

“Got it, Boss,” Matey said, and crouched near the door. She was good at falls. Before the clown gigs she worked grocery stores for insurance money, pulling what they call Slip and Falls in damp aisles, taking out injury claims.

“Walk and fall? That’s it?” I said.

Crack pulled a cigar from her suit-coat pocket. Twirled it in her fingers. “Listen, Sniff, let’s keep this one simple as our clientele. They get what they asked for.”

We came between appetizers and the entrée as an elaborate dinner bell, a fancy signal to corporate employee-guests: move from drinks to the dining hall. Soon enough, the music started, then a strobe light cut in. Crack didn’t say there’d be a strobe light. Anybody can do Chaplin in a strobe, but the things make me sick.

Matey took off, feet splayed and cane swinging. Crack followed Matey, with me a ways behind. We waddled like penguins while the flickering strobe made us into a stop-action film.

More than that, the strobe made me queasy. It was like being hit in the head.

Matey smacked into the back of a chair and stepped on the crossbar. The chair flipped backward under her foot. Matey sailed forward over the top. She was in the air, diving, cane flailing out to the side. On the way down she rolled into a somersault, all in the agitated, panicked heartbeat of the strobe. In that light the world was a fragmented place—a hand to a mouth, a spilled drink, a turned head—everyone diced into bits of existence.