Читать книгу Clown Girl - Monica Drake - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2.

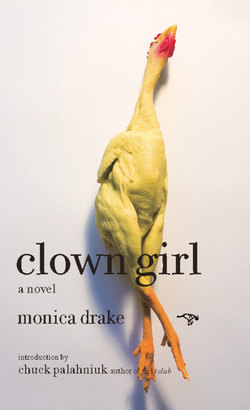

My Chicken, My Child!; or, Clown Bashing Lite

AT THE HOSPITAL DON’T SHOW UP IN CLOWN GEAR, PAINTED with the lush designs of clown face, because if you do, even clean underwear and an ambulance ride won’t win your credibility back. They brought me in on a gurney. Somebody said, “She looks a little pale. Ha ha!” He thought I was passed out. I saw him through my eyelashes, hoped he wasn’t my doctor.

Don’t tell them you’ve lost your rubber chicken—don’t let on that the rubber chicken matters, even if that chicken was half your act, your only child, love made manifest.

I told the EMT s about the rubber chicken on the ride over. “Somebody has to find it,” I pleaded. “I can’t lose my chicken.” They didn’t blink.

In the hospital, the EMTs unbuckled the gurney seat belt straps. I half-sat up, sick and limp, then climbed onto an ER cot and closed my eyes again. My mouth was dry, clouded with words I wouldn’t say.

“Another clown bashing?” a triage nurse asked. She lifted my arm and slid on the blood pressure cuff. There’d been a string of clown bashings in town. Hate crimes. Meringue pies full of scrap iron, fire extinguishers at full blast. Gary Lewis and his pack of Playboys, they had it wrong—not everybody loves a clown. The crimes were never prosecuted; clowns didn’t come forward. What do you say? Officer, a joke’s a joke, but only when it’s consensual!

The blood pressure cuff squeezed my bicep tight as a fist, like a dime-store security guard with a shoplifter. The black balloon of the armband throbbed against my pulse. A second nurse shook his head. “Self-destructed, this one.” With a sharp bite, he slid a needle in the back of my hand to hook up a saline drip.

Some people hate clowns, others are afraid, though hate and fear are really one and the same. Those coulrophobics, with their Fear of One Who Walks on Stilts. Fear of one with special skills, clown skills. My only skills.

Nobody cared about my chicken, my child.

The blood pressure cuff dropped away in the release of a deep exhale. The first nurse swabbed my makeup off. She hit me with a damp cotton ball in fast jabs. My face was reflected in the chrome of instruments. The jabbing swabber left white streaks along my chin and blue-black rings that seeped into the creases around my eyes. My lips were still pomegranate red, more like a tweaking hooker than a clown. The intake nurse said, “Rest quietly. Breathe. Let yourself hydrate.”

I sipped the air-conditioned air of the hospital like water, in tiny breaths. My heart knocked against my chest like a bird against a window.

She said, “Do you have I D?”

I sat up, fished a hand around inside my sun-hot bra, and pulled out two curled photos. The first photo was of a couple standing on the end of a pier, far away and blurred. Unrecognizable. It was a photo of my parents, so young they weren’t even my parents yet, so young they were still in black and white. So young they were still alive, hadn’t met their fate on a winding California highway. This was the only picture I had of them and I kept it against my skin, close to my heart. The second photo was of Rex Galore in full costume and full color, breathing fire, and when I saw the photo all over again it was as though he were the one who made me warm that day, not the sun at all but Rex’s breath against my skin, his fire act. I dropped the photos on the cot and fished in my bra again until I found my Clown Union card plastered to the sweat of my lower left boob. It came up stuck to my prize patron saint trading card, St. Julian. There was ink on my skin where the card stuck, transferred and reversed into a tattoo by the heat.

The union card lay damp and ragged in the nurse’s clean palm. She put it on the counter.

“I don’t leave home without it,” I said.

The nurse didn’t say “crazy” but she did say “social worker.” She patted my leg. “Let’s get someone for you to talk to, all right?”

“Talk to?” Talk therapy was clown treatment. I could barely hear over the knock and flutter of my own pounding heart, the buzz in my head. I needed a doctor. I gathered my wheezy breath. “Do most people take a fast ride here in the Blood Mobile just for the conversation?”

If I had a broken bone, a concussion, or was in shock, they wouldn’t sign me up with their social worker. What if I were an old man, overweight, near the end of a life of beef and sherry? That’d show a history of self-induced statistics toward cardiac arrest—slow suicide. But still, that man would get more than a layman’s priest.

I was a clown and got clown treatment: placating voices, a lack of concern. It was Clown Bashing Lite. I said, “If I were a sacred yellow Hopi clown, my people wouldn’t treat me like this.”

The face swabber came at me again with her damp cotton ball. “Treat you like what, dear?”

Dear?

“That’s exactly what I mean!” I pointed at her. I couldn’t explain. She wouldn’t understand, and nothing would change anyway. But if I were a Hopi clown, it might be said that I looked into the grave and climbed back out, traversed a fine tightrope and made it back for an encore. I’d earn a place of honor.

Instead, the male nurse told the swabber, “She fainted on the street. Fell down.” He made an arm gesture, like a tree falling, from elbow to palm. “Maybe hit her head.”

The fall was a symptom, not the cause. I said, “I didn’t hit my head.”

My left arm pulsed and buzzed, my head hummed; my heart beat against my breastbone like a fist throwing a punch. I caught my breath and said, “How about a doctor? Could I talk to a doctor?”

The triage nurse said, “Do you have family we could call?”

The photos lay curled on the cot. I had all the family I needed in Rex Galore. Better than a phone call, they could bring Rex home, fly him up from San Francisco, steal him away from his interview with Clown College. Then I’d be cured.

When Rex was in town, I’d tell him about the baby we lost. I’d look into his painted face, his brown eyes circled with blue. I’d tell him about the rubber chicken, our pet Plucky, our only child, now gone. After I told him, I’d sleep.

I hadn’t slept in a week.

I needed to lie down with the solidness of Rex’s bony knuckles, his knobby knees next to mine, his skinny butt and wide acrobat’s shoulders and the length of him stretched out on the bed beside me. His arm would be an awkward rock of a pillow below my head. My chest was tight and my hands were numb. With clumsy hands, I scrawled Rex’s name and a phone number, the number for a clown hostel. I’d seen the hostel once, where it sat on a field of green and overlooked the blue of the San Francisco Bay.

The nurse said, “Long distance?” Like she expected instead a whole family nearby, maybe packed into a tiny Studebaker idling in the hospital parking lot.

“He’s the only family I’ve got,” I said.

The second photo, my parents? That was ancient, ancient history.

A doctor listened to my chest. Only then did they hook me to an EKG. The EKG spit out a code of dancing lights. On the electrocardiogram, I watched my heart like a muted mouth open wide; it screamed one silent word repeatedly. The emergency room doctor read my heart’s code, and made the translation: Ni-tro, Ni-tro, Ni-tro.

That was the word, my heart’s demand, the blood pump’s room service order.

Abnormal Sinus Rhythm, the doctor said. Too little blood pressure in the chambers. “We’ll set you up with a cardiologist,” he said. “Get a second opinion.”

They gave me nitroglycerin. They gave me potassium. Eensy weensy pills to do a big, big job. I would’ve liked nitroglycerin first thing—that tiny tab of a pill under my tongue was better than breathing, better than food. In seconds it brought my arms into circulation, put my head on my spine, made my spine calm again down my back, my chest at ease.

Somebody said what I had was a Heart Attack. Cardiac arrest.

I lay covered with a thin hospital blanket, shivering under the cooling water of the IV drip. In ICU, instead of heart attack, they said Wait for the cardiologist. Wait for his diagnosis. Then my condition became a heart problem, an episode, a bad spell. Anxiety.

The staff said it was a flutter, palpitations, a murmur. That bird against the window. With each passing minute the need for potassium and nitroglycerin drifted into the faded corners of collective memory, off to intermission, a perpetual smoke break in the cafeteria of the False Alarm Wing.

It happened, but nobody believed it.

Don’t tell doctors your dreams, ever. Don’t tell them your menstrual cycle. Don’t say you felt anything in your head, or that you might’ve known. If they ask about street drugs, which they will, say no, no matter what. If you say, I feel anxious all the time, you’ll get Valium. Otherwise, you’ll get what they call “mood equalizers,” daily doses of who knows what, a gambler’s crapshoot in tinctures of chemicals.

As a clown on the street, I had to keep my wits. I couldn’t take their chemicals.

Don’t tell doctors anything.

A woman came to my room and asked, “Are you a certified latex-free clown? I run activities in the children’s wing, and we’re always looking. So many kids have allergies these days—”

I reached for my bag and pulled out a handful of balloons. She jumped back, like I’d released biological warfare, and left just as fast.

The intake nurse found me in ICU. She dropped my torn slip of paper on the nightstand. “Mr. Galore is unavailable. We’ve tried a dozen times.”

Worst of all—and what I did—don’t cry even when they don’t help you, even when they only want a urine sample to charge you for a drug test you don’t need, even when the third or fourth doctor asks you politely, again, about the cocaine you already told them all you don’t use.

Clowns and coke, clowns as junkies and drunks—doctors can’t see it any other way, but I was an artist. The junkie drunk clown thing wasn’t in my bag of tricks.

THE NEXT MORNING, THE HOSPITAL CURTAIN WAS PULLED back from around my bed with a sharp scrape of metal rings on a metal bar. “Breakfast,” a man sang. He put a tray on a tiny table across my waist and powered up the bed until I was sitting. “Wake up. Let’s get some lights on.”

I said, “I like it dim.” The room was a quiet cave, a hiding place, time immaterial.

He snapped on a light as though he hadn’t heard me, then said, “Or maybe this one, over here,” and flicked on another beaming fluorescent.

“Off is good,” I said.

“Or maybe a reading lamp,” and he turned on a third, out of my reach. Soon the whole room was blasting bright, and it was clear who ran the show.

A dietician’s note on the side of the breakfast tray read, “Low fat, low sodium, no caffeine.” I saw between the lines, into their code: Low patience, low humor, no tolerance. Clown.

The man pulled open the blinds with a clatter. My view was an alley. He left me in the glow of every light, my own electric sun.

I stabbed a plastic spork into the sponge of pancake, lifted it, and the heavy dough fell off the stubby tines. I tried again. Halfway to my mouth, pancake dropped to the front of my robe in a sticky smooch. I picked the food up with my fingers, syrup trailing, and licked the empty spork; the grease slick of margarine on the back of the rounded plastic was a non-food I hadn’t tasted in years.

Mid-lick of the spork, a cardiologist ducked into my room. He reached to shake my hand, and blew into the steam on a Styrofoam cup of coffee held in his other hand. I reached back with sticky fingers, breakfast rocking like a raft on the ocean of my lap.

“Well, yes,” the cardiologist said, and drew his hand away. “Nice to meet you.” He searched for a place to set his coffee on the bedside table, then reached for my thin paper napkin and wiped his fingers. Napkin stuck to his fingers in shredded tufts like an old man’s ear hair. He sat on the edge of my bed and puzzled over my chart like it was the Sunday Times.

“Don’t take it personally,” he said, finally. “The long delay yesterday, the difficulty with diagnosis. We go by statistics, judge by likelihood. Thin women, young as you are, generally don’t have heart trouble.” He slid a pen from his front pocket. Made a note.

Thin women. Clown women. Skinny girls like me.

Not heart attacks, no. Skinny women have other problems. They double over, pelvis in knots, and drop stillborn babies in public places—bloody, tiny, and blue. Women have anxiety attacks, not heart attacks; they worry too much, burst into tears, faint. Ta da!

Crazy.

“It seems your mitral valve wasn’t closing properly,” he said, and made a hand gesture like a quacking duck. His thumb snapped against his fingers. His pen, still in hand, pointed up through the duck’s beak like an oversized cigar. “That made your aortal valve work overtime. Maybe a lack of potassium. Do you eat regularly?” The duck flattened, and swirled down to my plate of pancakes.

I shrugged.

He said, “What’d you have for lunch yesterday?”

“I worked through lunch. A gig,” I said. “I had a latex ham sandwich. It makes pig sounds, squeals under pressure.”

He didn’t laugh but only nodded, made a note, then tugged at an invisible beard on the tip of his chin. I said “It’s a prop, right? For the joke: how’s a ham sandwich like a stoolie?”

“What else, what else?” He waved a hand in circles, like a traffic cop asking me to pull forward.

“Exploding bonbons, smoking gum. A self-refilling pitcher of white fake milk. That’s a sight gag that wins every time. I’m trying to cut back on the fake milk, but it’s hard. Audiences love it, Doc. I can’t give it up.”

He made another note. Without looking at me, he said, “What about real food?”

Real food made me want to vomit. For weeks, I had no interest. My pelvis was an empty room, food an unwelcome guest. Instead of answering, I asked, “You think caffeine could’ve brought this on?” It read decaf only all over the dietician’s card on the side of my breakfast tray.

The cardiologist looked up from the notes he was writing. “You know, that’d be an interesting experiment. We could get you all jacked up on caffeine, see what happens. But for now, try to eat a little more. Start with your breakfast.” He tapped my tray. “It’s good stuff.”

He had the sort of personality that would let a body live a long time—inquisitive, delighted, and unconscionable. He was money and science, old skin and thinning hair and rings worn into grooves below his knuckles like metal around wood. He cleared his throat and said, “Your chart shows you were admitted through the ER not too long back.”

I didn’t answer.

“What’s this about a miscarriage?” he asked. He smoothed a frazzled eyebrow with the side of his thumb.

Miscarriage! The word made it sound like I dropped my juggling pins or fumbled a football instead of floundered my way through the blood and cramps of lost life. I said, “Let’s talk about the exploding bonbons again. I’ve got this great act. I call it the Girl Scout Shuffle.”

“D&C performed,” he read. “It’s been…” he counted out the days. “Almost two weeks. Are you still bleeding?”

“What do you think, it was twins? Died a week apart?”

“I assure you, it doesn’t work that way.” Then he asked again, “Tell me, are you bleeding?”

“You tell me—when are my fluids no longer your business?” I was barely bleeding. Nothing to mention. There was no dead baby cradled between my hips. Not anymore.

He said, “Dear, we’re in the body-fluid business. You don’t have a fever…cramps?”

I said, “I came in for help a while back, and that’s over now. I’m here again, sure, but it’s a new show. Act One.” I didn’t even want to think about the last round in the ER: pregnant, then not pregnant, and the drama was over. Curtains closed. There would be no tiny Mr. Galore. No miniature Rex. No granddaughter to my lost mother, grandson to my once-present dad, our tightly pruned bonsai of a family tree.

Soon enough I’d tell Rex about the trip to the ER, but I’d tell him when he came home. And until I told Rex, why tell anyone else? I was two months pregnant when the blood started. Rex was one week out of town.

The cardiologist nodded and wrote on his chart. “Any pain now? Bloating?”

I shook my head, a slow side to side.

“In a miscarriage, you can lose a lot of blood. Become anemic, have complications. Maybe we should get someone in here to do a pelvic.”

I said, “It was my heart this time, right? A whole different issue, different tissue.” I didn’t have claws digging into my sciatic nerve or the wrenching in my gut. I wasn’t sifting through blood clots brown and gelatinous as chicken liver, looking for the blue tint of the birth sac. “You can’t reach my heart through my hoo-ha—and you’re not the first man I’ve warned that way.”

“Your hoo-ha?”

“No pelvic,” I said. I looked around for a balloon to tie, a way to ease my nerves. “Can I have one of those rubber gloves?” I’d make the five fingers into a tiny Madonna of the Rocks.

The cardiologist nodded, a meaningless gesture, and didn’t hand me a glove. He said, “OK, well. There is one more test I’d like your help with.” He lifted my sticky hand, looked at my fingernails. Each nail was painted a different color, like a box of crayons.

“For clowning,” I said.

He put my hand back on the bedspread carefully, as though my hand were breakable. “We’d like to check your adrenals.” He patted the back of my hand. His own hand was laced with a rope of veins, like rivers drawn on a map.

A nurse came in with a paper bag. She said, “Excuse me. Your friends brought this.”

“Friends?” I repeated, hopeful, and took the bag from her. Rex was my friend. He topped the list, my only friend at times.

Inside the bag was one juggling ball and an envelope of twenties. No rubber chicken. In blue pen, on the outside of the envelope, it said, They docked you for leav’n early. Otherwise, it’s all here.—Crack.

Matey and Crack. They were co-workers, not friends. I put the bag beside the bed.

The doctor wrote a note on a prescription pad. “The adrenal test is simple. And it’s precise. But we need you to collect twenty-four hours of urine.” He gave me the note. “Take this down to the lab, they’ll explain the process. You’re heart seems OK. Today’s EKG looks good.”

Still, I could point to a place in the front of my skull where my head was full of the hum of bees, an incessant and displacing rattle that moved in over thoughts I might’ve had. If this were a clown act, I’d hold a hand to one ear. Bees would fly out the other side.

I asked the cardiologist why an electrocardiogram was called an EKG, instead of an ECG.

He said, “Nazis. Nazis invented the machine.”

After he left, I found a napkin on my breakfast tray and wrote that down: EKG = Nazis.