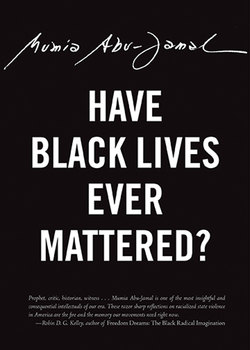

Читать книгу Have Black Lives Ever Mattered? - Mumia Abu-Jamal - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеWE ARE BLIND TO EVERYTHING BUT COLOR

July 5, 1998

“In order to get beyond racism, we must first take account of race. There is no other way.”

—Justice Harry Blackmun, University of Calif.

Regents v. Bakke (1978)

In cases decided every day across America, the theory of color blindness said to govern the judicial process is a reflection of the flawed notion that the mere mention of race is somehow racist. Consequently, the law serves up yet another legal fiction, which obscures the complexity of real life, in furtherance of a false and fatal simplicity.

There can be no sustained study of American law without coming face to face with the racism that drenches judicial thought, in a clear, unapologetic tone that leaves no question as to the objectives of the court.

It is obvious that the objection on the part of Congress is not due to color, as color, but only to color as an evidence of a type of inferior civilization that it characterizes. Yellow and bronze, as racial colors, are the hallmarks of Asian despotisms. It was deemed that the subjects of these despotisms—with their fixed and ingrained pride for their particular culture, which accepts the subordination of the individual and community to the supreme personal authority of the sovereign, as the embodiment of the state—were not well suited to further the success of a republican form of government. Hence they were denied citizenship.

The anti-Asian bias that oozes out of the 1921 decision Terrace v. Thompson (U.S. District Court, Washington), for example, which is clothed in a kind of quasi-sociological justification, actually justified laws in Western regions that outlawed the sale of land or property to Japanese people, on the basis of ineligibility of citizenship. Until the 1950s, the Chinese and other Asians were denied naturalization.

Despite our pretensions of being “color blind,” scholars assure us that, over a century after the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1884 became law, the court case that upheld the Act remains good law to this day.

The U.S. Supreme Court majority in Chai Chan Ping v. U.S. (1889), found “the presence of foreigners of a different race in this country, who will not assimilate with us” to be properly excludable. For over a century, such decisions that made whiteness the sole prerequisite for U.S. citizenship, and explicitly excluded people it deemed “nonwhite,” had, at their very core, not “color blindness,” but color consciousness distorted by a profound sense of white supremacy.

It is fitting here to note that in 1935, the two countries that had racial restrictions on naturalization in common were Hitler’s Germany and the United States of Americas. Color blindness?

For the better part of two centuries race has been at the very heart of law in the United States. It remains so despite the latest fashion of the legal fiction of “color blindness.” How people are treated in court, how they are charged, and how they are sentenced are direct reflections of what race and ethnicity they are and how such traits are regarded by white America.

Several years ago, a prominent American law professor asked his students to imagine they would wake up the next day as Black folks. The white students reasoned that such a “disability” required monetary damages of a million dollars a year for life.

Why damages, unless color does matter? Unless whiteness is a valued property which, when lost, demands a premium payment? And Black is devalued?

Americans are blind to everything but color.