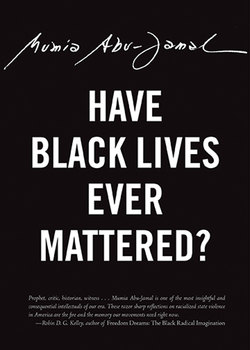

Читать книгу Have Black Lives Ever Mattered? - Mumia Abu-Jamal - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеA HISTORY OF BETRAYAL

October 29, 1998

United States history is a study in denial, for much of what is taught as history in the schools of the nations bears little relationship to the lives lived by millions of men, women, and children on the land we now call America.

Most schools teach that which is safe, and mostly false; so much so that shock and disbelief are usually the result of telling a history that reveals that many of the men called “Founding Fathers” were enslavers, visceral racists, and, in a word, creeps.

Dedicated to the erection of a “white man’s republic” (as supported in the 1857 Supreme Court opinion by Chief Justice Roger B. Taney in Dred Scott v. Sandford), many of the nation’s leaders, congressmen, and presidents were virulent racists who made every effort to deny any semblance of justice to Black freedmen in the hellish aftermath of the Civil War. How many Americans know that more than 37,000 Black men died while serving in the Union Army? The people who fought to preserve the union, who fought against secessionists and enslavers, returned to a South where virtually every promise made to them was shattered and broken, often by the very government they had fought to defend. While the war was raging, General Sherman assigned thousands of acres to freedmen, on the land that was vacated by white enslavers or confiscated. These lands, on which more than 40,000 freedmen and their families tussled with the earth to create a life, were summarily snatched away from them by the U.S. government. In October 1865, General Howard traveled to “Sherman land” to revoke titles to lands confiscated during the war, in order to return them to their previous white owners.

General Howard’s instructions to the so-called freedmen? “Put aside your bitter feelings,” and “become reconciled” to your old enslavers. The people who had suffered indignity and bondage for centuries, who worked to enrich the national economy, told the U.S General: “No, never,” and “can’t do it.”

Howard Merrimon, formerly enslaved in Mississippi, described the condition of emancipated Black folk during the period of the Great Betrayal, 1865–1866:

No land, no house, not so much as place to lay our head. . . . Despised by the world, hated by the country that gives us birth, denied of all our writs as a people, we were friends on the march. . . . brothers on the battlefield, but in the peaceful pursuits of life it seems that we are strangers.9

Abolitionist Wendell Phillips aptly noted that without the vote, Blacks would be doomed to a “century of serfdom.”10 He wasn’t far wrong.

Blacks fought and died for the Union, and after the war they were forsaken, treated as if they were the enemy of the very nation that they had fought and bled for. Here, in the aftermath of carnage, white supremacy was the law, and Blackness was a crime. That was the reality that leads to today, the history that created the days and nights of this very hour.

When the United States was formed, it was constituted by an act of compromise that left half of the nation slave, and the other half of the nation “free.” A hundred years later, and even after the raging horrors of war had ripped the nation apart, a new compromise was reached between the North and South. In the words of one supporter of President Andrew Johnson, that compromise was based on this central tenet: “Keeping the Nigger down.”11

For a century after “Emancipation,” Black folks, in the main, were denied every substantive right of the U.S. citizen: voting, holding office, jury service, freedom of travel, freedom of assembly, freedom to collective bargaining, etc.

Far from free or equal, Blacks found themselves condemned to a new life where the state took the place of the slave master, and did everything in its power to control Black labor in the interests of the landowner’s class.

For most of American history, so-called “law” was merely white whim. Black life, considered cheap in slavery, became “free” and worthless in “freedom.” As historian Eric Foner notes:

Sheriffs, justices of the peace, and other local officials proved extremely reluctant to prosecute whites accused of crimes against blacks. To do so, said a Georgia sheriff, would be “unpopular” and dangerous while an Arkansas counterpart told a [Freedman’s] Bureau Agent that to take action against a planter who had defrauded freedmen “would defeat him in the coming fall election.”12

That was the reality that leads to today. The roots of a repression that still block sunlight, and makes Black life so hellish still.