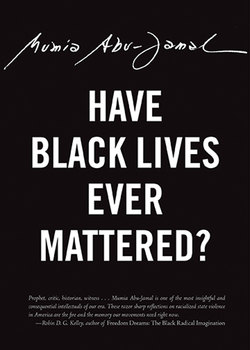

Читать книгу Have Black Lives Ever Mattered? - Mumia Abu-Jamal - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHE LAW AGAINST THE LAW

June 20, 1998

“If it took the White majority more than two hundred years to understand that slavery was wrong, and approximately one hundred years to realize that segregation was wrong (and many still don’t understand), how long will it take them to perceive that American criminal justice is evil?”8

—Paul Butler

As long ago as 1880, the United States Supreme Court, in Strauder v. West Virginia, ruled that the “defendant does have the right to be tried by a jury whose members are selected pursuant to nondiscriminatory criteria.” Over a century later, in 1986, the nation’s highest court reiterated this principle in Batson v. Kentucky, for although a century had passed, it remained all too common for trials to be conducted before all-white, or predominantly white, juries, in cases where it appeared as if, besides the defendant, only the judge’s robes were black. It also shows us that no matter what the Supreme Court does, the judiciary, prosecutors, and police will do what they want to with impunity, especially when Blacks are defendants. For, if Strauder was the “law” why did it need reiteration in Batson?

Strauder was ignored in U.S. courtrooms for 106 years, just as Batson is today. As any law student knows, the theory of law is vastly different from its practice. Shortly after Batson was decided in 1986, an assistant district attorney in Philadelphia gave a class to district attorney trainees, teaching them how to violate the spirit of Batson by ensuring that most Blacks would be removed from jury pools. Much time has passed since Batson, and yet cases are upheld today where a Black defendant sees Black jurors removed for bogus reasons. What is the “law”? What the Supreme Court says, or what district attorneys do? What the cases say, or what trial judges allow?

The “law” is what is allowed every day in real cases, in real courtrooms, across America, and not what is written in dry, dusty books read by hoary scholars. Seen from this perspective, Batson is still not the law, despite what books may say. And if the process is not tainted enough, what of the consequences of such a process?

Recently, the governor of a state that boasts a spate of Batson violations—Pennsylvania—signed Senate Bill 423 into law, thereby enacting a statute that forbids a death penalty appeal based on the following:

a) claims that Blacks are more likely to be executed for the same crime than whites;

b) claims that an indigent defendant is more likely to be executed than a rich one;

c) claims that a death sentence is excessive or disproportionate to the penalty imposed in similar cases.

This is, essentially, a law against the “law.” It is a proclamation of the supremacy of the political over the legal. It is a statute that explicitly enforces the value that white life matters and Black life does not. It is a law of the state that exclaims the inherent superiority of the wealthy over the poor, and that allows the basest disproportion to masquerade as “justice.”

It is a statement that reflects a hellish, unequal status quo that still has not changed no matter what the U.S. Supreme Court says, and no matter how many times it says it.

It is the law of what was, what is, and what may be.