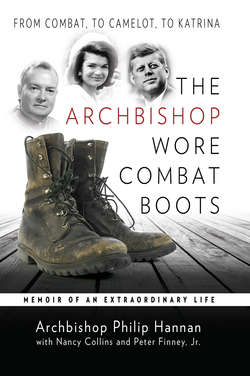

Читать книгу The Archbishop Wore Combat Boots - Nancy A. Collins - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 4

Four Years in Rome

Johnny Linn and I embarked for Rome in September 1936 from Hoboken, New Jersey, aboard the S.S. Exochorda, a combination freighter-passenger vessel of the Export Line. It was the season for the equinoctial storms. These are violent rainstorms that occur at or near the time of the equinox (where the sun is directly above the earth’s equator), normally occurring around March 20 and September 23 each year. Just a half-day out of port we encountered a hurricane that blew us almost all the way to southern Europe. Few meals were eaten, and the porthole in our cabin, punched open by a swell, left us swamped. The ship’s roller coaster movement was so intense that the dining room staff had to wet tablecloths to keep plates and cups from slipping off the table and crashing to the deck. Eventually, we arrived at Naples, where we were escorted to Rome by Charlie Gorman, a third-year seminarian from Baltimore (stopping long enough in Naples to see Mount Vesuvius and visit the Shrine of Our Lady of Pompeii where, inside the door, a mother breast fed her baby while saying her prayers — welcome to Europe).

The North American College in Rome was located in a 400-year-old building at Number 30 Via dell’ Umiltè, named after a stunningly beautiful painting in the chapel, Our Lady of Humility, by Guido Reni. Following a brief stay there, we traveled to the College’s summer villa for seminarians — the Villa Caterina — located close to Castel Gandolfo, the pope’s summer residence. Besides a swimming pool and tennis courts, the view of Rome from the main building was spectacular. Though peaceful, the feeling among the Italian populace was anything but serene. Adolf Hitler, in the midst of his rabid campaign to conquer the world, had convinced Benito Mussolini, following “jackal-like,” to share in the spoils of his conquests. The war in Spain, meanwhile, also winding up, had unleashed divisions of soldiers throughout Europe. Everyone, it seemed, proclaimed a political aim and wore a uniform — myself included. While each seminary had its own distinctive garb, ours, a black cassock, trimmed in light blue with a red sash, was particularly so. As a result, we dubbed ourselves “bags,” derived from the Italian world bagarozzi (meaning cockroaches), a derisive term used by anticlerical Italians.

In October, we packed up and left the villa to return to Rome and the North American College, where we would begin our studies. “Packing up,” in this instance, was literal: that is, picking up your actual mattress and clothes, which were loaded onto a truck and, entering via the rear of the college, dumped on the ground. Instantly, a mad scramble ensued as each seminarian fought to grab a good mattress and haul it off to his room. Our first Christmas at the College, meanwhile, taught us to be thankful for small favors. Due to inconsistent heat and electricity, we were forced to wash and shave in water so cold it barely remained liquid. As it turned out, the College, aiming to impress visitors to the annual ordinations, turned on the heat only in December. All classes at the Gregorian — an old Jesuit university commonly called the “Greg” — were conducted in Latin, as well as Hebrew, which was also taught from a Latin text. Both the College and the “Greg” were a mere stone’s throw from the famous Palazzo Venezia, the office of Mussolini.

Mussolini, a classic demagogue, was a real piece of work. Only five feet seven, he never addressed his troops from street level, instead, elevating himself in the public eye by sitting on a horse or standing on the second-floor balcony of the Palazzo Venezia, where he would whip his audience into a frenzy. When Italian soldiers appeared in the piazza below his balcony, he would incite them. Since each carried a short sword, the end of Mussolini’s orations, detailing his plan to restore the former glory of Rome, were marked by soldiers, trained to punch their swords into the air, shouting: “Duce! Duce! Duce!” If the cheers weren’t loud enough, Mussolini disappeared inside. Seconds later, when one of his stooges popped out on the balcony, the people would cheer, and Mussolini, depending on how he felt, would return for an encore — or five or six. While overrating Hitler, Mussolini underrated England and France. Moreover, he had his own goals: restoring the Roman Empire, where he would be enshrined in the pantheon of famous Roman emperors.

Seminarians from the Archdiocese of Baltimore in the North American College. I am standing on the far left

My first walk in Rome was, of course, to St. Peter’s Basilica, which was simply overpowering. Exhausting every faculty of my mind and heart, I tried to grasp its enormous scale and breathtaking beauty. St. Peter’s was not only an unbelievable work of art, engineering, and history, it was, above all else, an inexhaustible source of inspiration. It is not simply the size of St. Peter’s that is the source of its grandeur but also the congruity of every unique element of the whole piazza: the stupendous church that stands like a creed (credo) of faith; the arc of the Colonnade of Bernini, which welcomes the human family to its place of worship; the paved surface of the piazza that conveys charm to its visitors. Of course, the Scavi — or underground excavations — attest to the presence of St. Peter, the first Vicar of Christ on earth and our pastor in the faith. As a Washingtonian, the dome of St. Peter’s bespoke the capitol of the United States. Not surprisingly, there was an architectural legacy responsible for that similarity. Christopher Wren had Michelangelo’s dome of St. Peter’s in mind when he designed St. Paul’s Cathedral in London in the late seventeenth century, and Thomas Ustick Walter, the architect of the Capitol dome in the 1850s, was inspired by Wren’s design. Not surprisingly, all roads led back to Michelangelo.

After a few visits and prayer sessions, I finally began to comprehend St. Peter’s. And it became a home — one that never dulls but continually uplifts the soul with a fresh surprise or thrill. In short, it possesses the spirit of God, never lacking inspiration, never growing old. The tomb of St. Peter, the Pieta, the Blessed Sacrament chapel, the underground excavations (Scavi), mosaics, and marble were stunning. But the discreet feature that truly epitomizes St. Peter’s is the near invisible mosaic directly above the central front door — the Navicella (little boat) — a respresentation of Christ rescuing St. Peter during the storm on the lake. Having bade St. Peter to come to Him across the water, Christ is saving Peter as he begins sinking from lack of faith. As such it typifies the history of the Church: “It is battered but never sinks.” That treasured mosaic was preserved from the old St. Peter’s and placed in the new basilica (dedicated in 1626). Because of its great message of the power of faith, it was placed in the vestibule as a final inspiration to the faithful leaving the cathedral.

St. Peter’s Basilica

One must live with St. Peter’s on a daily basis to truly appreciate its majesty. One of my favorite stories is that of the Egyptian obelisk in the center of the piazza. Following the custom of the time, the Emperor Caligula brought it to Rome, erecting the obelisk at a spot near the Palace of Nero before relocating it near the first St. Peter’s Church. After the completion of the “new” basilica in 1586, Pope Sixtus V decided to place the obelisk in the center of the piazza. Moving it, of course, was perilous, requiring the efforts of 800 men, 150 horses, and 150 cranes — all supervised by Domenico Fontana. To ensure calm during the delicate operation, the Pope decreed that any bystander making an outcry would be subject to the penalty of excommunication. As the men tried to lift the obelisk in place, it became apparent that the ropes were not strong enough, eventually becoming so taut they were unable to lift the spire, prompting a sailor named Byesca from Bodighera to yell out: “Water to the ropes!” His sage advice salvaged the operation, and the obelisk settled into place. In thanksgiving for the savvy seaman’s advice, the Pope awarded him the honor of having his village supply the palms to St. Peter’s on Palm and Easter Sundays.

As we new seminarians settled into our studies, there was an informal initiation ceremony at the North American College, a seminary which over the years garnered a reputation for being a bishop “factory.” Upper classmen would take you aside — always very politely — and ask that you recite the obscure prayer said before putting on your surplice. Then, when they had you reeling, they would ask: “Which course of studies do you want to follow? Do you want to be in the advanced courses?” Of course, everyone said yes. “So you’re saying you want to enroll in the course,” they continued, intent on embarrassing the guys with any such ambition, “that teaches you to be a bishop?” At that moment, you knew you’d been had — albeit all in good fun.

Life at the College, organized according to a camerata system with roots in the old Florentine educational society, centered on small groups of students gathered for learning. Each afternoon a camerata, eight to ten students living in the same section of the college and led by an upper classman — a prefect assisted by a “beadle” — would take walks. And though our group might pass another camerata inside a church or on the street, we weren’t allowed to mingle much less swap stories. My cam leader was Bob Arthur, a fellow student from the Archdiocese of Baltimore, who dutifully took us to all the important churches in Rome. Besides Bob, our diverse, congenial camerata was populated by types rebelling against the long-standing Roman traditions of behavior for seminarians studying in Rome. They included: George Spehar, a huge, Croat-descent from Crested Butte, Colorado; Frank Latourette from Denver, who, ultimately left the seminary to become a successful TV producer; Ed O’Connor and Marty Killeen from Atlantic City; Charlie Noll from Cincinnati; Tom Powers from Philadelphia; Jim Woulfe from Binghamton, New York; and Johnny Linn from Baltimore.

All Gregorian classes were in Latin, producing a challenging, immensely rewarding spectacle. Sessions in moral and dogmatic theology, for instance, were held in a huge aula seating, arena style, around 300 students from almost every nation in the world. There were no textbooks. The professors simply delivered their lectures in Latin as we, scribbling furiously, tried to keep up. Needless to say, three or four months were required to become capable of understanding and recording a whole lecture.

Although we had outstanding professors — each an expert in his field — we never really met them. Leaving as soon as the lecture was finished, they discouraged any attempts at conversation. If a seminarian happened to be late, the professor gave everyone permission to make a hissing sound, which I found rather childish. During class, meanwhile, the silence and solemnity were never interrupted except, that is, by an intrepid English seminarian whose raucous rooster cackle invariably provoked utter disgust in our lecturer. Though a few dared laughing, the culprit was never apprehended thanks to his neighbors concealing his identity. The courses, prepared for an international student body of nearly every race and nationality, were taught by equally diverse professors: Italian, Spanish, German, Dutch, French, Hungarian, and a lone American. As a result, teaching, emphasizing principles applicable to individual cases and problems, was, nonetheless aimed toward a worldwide Catholic congregation, ultimately making it impossible to conclude that there could ever be an American, French, or African Church. (Later in my priesthood, encountering diverse problems in diverse national and ethnic contexts, I thanked God for my education at the Gregorian.)

Examinations, held once a year in July, were a sheer terror. Students were summoned by name to sit in a chair opposite one of several professors, also seated and giving the oral exams which, being public, were open to any student who wished to observe. Inevitably, a group of Italian students, fluent in Latin, would gather to wallow in the discomfort of the less-talented, especially the Americans. In my case, I never had an examiner from the United States nor one with whom I’d actually taken classes. Talk about a home-field disadvantage! Standing near the Greg’s front door, a gaggle of pious, indigent women, begging and offering to say prayers on behalf of the nervous students, invariably pulled in a rich harvest of coins each day of scheduled exams. One first-year American student really cracked under pressure. Throwing him a softball question, the professor asked in Latin, “Quid est philosophia?” — “What is philosophy?” Rattled, the poor guy gave the first answer that leapt to mind: “Chi lo sa” — “Who knows?” — causing loud, audible snickering from the Italians in the audience.

Food at the North American College was lousy, mainly because the English, trying to starve the Italians into quitting their cooperative agreement with Germany, posted part of their navy at Gibraltar and the Suez Canal. As a result, not many good food products were getting in — resulting in delicacies like sardine soup for lunch. It got so bad, in fact, that the rector, firing the cook, allowed a committee including the seniors to search for a new chef, proving true the adage that “God so loved the world that he did not send a committee.” Ultimately, the rector hired a fellow from Hungary who was told that American seminarians liked pies. Finally, the big day arrived. The new cook was finally in charge and out came his pies — filled with spaghetti! It was the end of his — and almost the rector’s — career.

I became so intrigued with the current events and history of Rome that, aided by Ed Latimer, a seminarian from Erie, Pennsylvania, we published an annual magazine called “Roman Echoes” (dropping off the magazine at the printer, Vatican City’s famous Polyglot Press, afforded me the chance to get a snack and drink at the bar — a liqueur costing six cents — a rare treat in the days of food blockades). For one issue, besides normal stories about prominent visitors and major events, I decided to interview Giovanni, the elderly, respected waiter at the head table. “Of everyone you’ve ever served, cardinals, statesmen, presidents, and movie stars,” I asked, “who was the most outstanding?” Giovanni didn’t hesitate. “Buffalo Bill,” he shot back. “Now that was an extremely gallant man.”

Traveling through Europe

Each July, exams over, I traveled through Europe, often with my mother and father — always generously paying for traveling as part of my education — or brother Bill. Though mother was thrilled by European life, the Boss desperately missed his home-cooked meals back in Washington. In the summer of 1937, his first encounter with Italian coffee engendered instant pity for his son. Joining my parents for breakfast at a good hotel on Rome’s Via Veneto, I watched with amusement as Dad, inveterate “Irish breakfast” addict, ordered coffee, two eggs, and a small steak. “Si, si,” the waiter replied. When the java arrived, his first sip made him grimace. “Son, is this what they give you to drink every morning?” “Actually, our College coffee isn’t this good.” Subsequently, he slipped me extra cash to buy real coffee outside of the seminary.

In fact, the Boss made only one transatlantic trip, combining a visit to Rome with a pilgrimage to his native Ireland. Though he liked seeing St. Peter’s and the Pope up close, the hundreds of other churches and art galleries didn’t much impress him. As a result, we had to fool him into visiting Venice, which Mother desperately wanted to see, saying we’d merely pass by on the road to Ireland. Once in Venice, Dad hated the Venetian gondolas, seeing no sense in using canals as streets. Since he couldn’t swim, being in a town that was virtually underwater was a constant trial. As we walked through the glories of Venice, all Pop could say was: “When do we get out of here?”

Eventually, we made it to Adare, Ireland, the nearest town to Kilfinny where my father was born. (Surprisingly, I learned it had been the center for the revival of Irish literature, familiar territory for the likes of Yeats and Keats.) Hiring a car, we drove up to the house of our relatives in Kilfinny, a village so small it had a school and a church, but no resident pastor. My folks were overjoyed, however, when, upon seeing us, everyone shouted: “Glory be to God, look who’s here.” Immediately, my father’s cousins insisted that we move out of the hotel and live at their thatched roof cottage — a wonderful experience with food boiled atop the fireplace, tea served at every meal. That first day, however, we spent little time eating since Dad wanted to show us his “college” — a two-room, thatched-roof shack with sod floor that served as grammar school for his three years of formal education. Having to leave school to help support his family, he ended up on an estate in Adare, receiving a shilling — twenty-five cents — a day from the English lord who, owning even the broad stream, declared it illegal for an Irishman to fish in it. Nevertheless, Dad never expressed any anti-English sentiment since the lord had allowed his father, though infirm and unable to work, to live with the family in a small hut. Though the family’s abysmal poverty eventually forced Dad and his older brothers and sisters to immigrate to America, none ever bore a grudge against the English. As the Boss told me: “The English lord never forced my sickly father out of his home.” Standing there that day, I was never prouder of my father.

The trip really tapped into my father’s charitable leanings, albeit not always successful with the proud Irish. After visiting his cousin Mary Leo, we called on the parish priest. “I’m worried about my cousin Mary,” he told the pastor. “She doesn’t complain or ask for help, but I don’t know how she lives or who supports her. If you’ll accept it, I’ll be glad to send money to you each month for her living expenses.” Fixing my father with a withering glance, the priest replied: “Glory be to God, man, doesn’t she have any neighbors?” whereupon our visit ended. (In the evenings we caught up on everyone’s lives. Though most had close relatives in the United States, sending a sizable check each month, our Irish relations were extremely concerned about the decline in morality among the youth. “Don’t you know that they’re drinking cocktails now,” they said. “Did you ever hear of such a thing?”)

All too quickly, our stay came to an end, and we drove to Cork where my parents were catching their boat back home. As it turned out, it was the first time I saw my mother crying. “We’re leaving Phil all alone,” she sobbed. Though sorry to see my parents leave, I was raring to move on with the rest of my European travels. Given Mother’s passion for art and architecture, I knew she’d be back the following summer unless war broke out. And I wasn’t wrong. In July 1938, she indeed returned, this time with my brother Bill. Boundlessly curious, insatiably interested in art, we hit every museum and cultural site we could find. After visiting the basilicas and Vatican museum, we traveled to Florence, Venice, and Dresden, fulfilling mother’s lifelong desire to see Raphael’s Sistine Madonna housed in the town’s art gallery where we rushed straight from the train. My Lord, was it worth it! That glorious painting, the Blessed Mother holding her Divine Child in heaven, the sole object in a grand room, was instantly spellbinding, arresting one’s entire being.

It was in Dresden that we got our first taste of life in Nazi Germany. At the registration desk of a nice hotel, Bill started signing his name on the register. Just then two Nazi officers came up, brusquely shoving him aside. Bill, ever the impetuous lawyer, shoved back, hard. I intervened, stopping the set-to. “You and I can’t handle the whole German Army,” I told him as he calmed down. That evening, as we were leaving the room to join Mother for dinner, the hotel manager appeared at our room. “I saw what happened today,” he said. “Here are the keys to my car. You may use it as long as you are in Dresden.” Clearly, not all the Germans were pro-Hitler. My German extraction mother, meanwhile, was appalled at the behavior of the soldier and Hitler Youth. “These are not the Germans,” she said nearly once an hour, “that were in our family.”

My most enlightening — and frightening — experience happened when I was traveling alone on the Rhine steamer en route from Cologne to Coblenz. I was seated next to an elderly German woman when a group of boisterous, arrogant Hitler Youth passed by. Cautiously, my seatmate turned to me, asking, “You are an American, are you not?” Answering yes, I showed her my passport. When I said that I came from a family of one sister and seven brothers, she happily revealed that she, like my mother, had had seven sons. “We older people,” she sighed, “will never have peace in this country until we have killed our own sons!” Her devastating description of Nazi Germany haunts me to this day. It also confirmed my conviction, based on my visits, that a conflict with Germany was unavoidable. The country was preparing for war with everything, and everyone was under surveillance. Once your train left Italy and stopped in the first German town, German soldiers jumped onboard, rifling through identity papers, books, and magazines, confiscating all reading material, especially foreign-language publications. Even more unnerving, once having crossed the border, everybody greeted each other with: “Heil, Hitler!” a salutation I certainly never returned.

Eventually, we made our way to Paris, then onward to my favorite cathedral in France in Chartres. Keen to see the Cathedral’s world-renowned stained glass windows, the moment was bittersweet as we watched workmen taking them down in order to protect them from bombs. Fervently, we prayed for peace.

In the United States, meanwhile, many intellectuals, including Father Fulton Sheen, were convinced that there would be no war because, as Sheen put it, the “people would not permit it.” Obviously, he had never been to Germany. Had he, he would have realized that the German people had already given their permission — to the Nazis.

For me, the turning point in the rise of Hitler was the collapse of Austria — the Anschluss — in March 1938, since it enabled Hitler to prove to himself, his people, and the world that he could take another nation with neither France nor England coming to its rescue. Certainly he fooled the Viennese Cardinal Theodor Innitzer who, giving in, signed a declaration supporting the Anschluss with the fateful words: “Heil Hitler!” Though Pope Pius XI later forced Cardinal Innitzer to recant his statement, the damage was done. In the summer of 1938, fellow seminarian Butch Burke and I visited Vienna, which was bereft of tourists. The city was dead. At the famous Rathskeller, we were the only dinner guests. Being such rare birds, we got super treatment. When we departed the restaurant, the crowd cheered, leaving us agape and not knowing what to do — a history lesson I’ll never forget. When Winston Churchill called the approaching war “The Gathering Storm,” his image perfectly matched my personal observations. In recent years, trying to evaluate why I am so troubled by hard rock music — especially its constant, pounding beat — I suddenly realized that it reminds me of young Nazi soldiers, pounding along the pavement in unison, intoxicated by their percussive sound.

I suppose that’s the reason that to this day I am always a bit distraught over the utter incapability of the people of our time — the younger people — to comprehend the evil of the tyranny of Communism. Perhaps theoretically they can acknowledge its danger, but it is to be appreciated only in the fullness of its experience — the degradation and torture of people. A complete degradation of the dignity of humanity, a total disregard of human rights. No one can see how bad it is from a book. One has to see it in action.

Mussolini’s efforts to partner with Hitler were pitiful. The Italians could not be fanaticized and always retained an appreciation of Christian culture. In a barbershop in Naples I heard a customer lecture the barber about the advantages for him to join the Fascist party. Finally the man told the barber triumphantly, “The Party would send your son to college without any charge.” The barber replied without a pause, “Yes, and at that point, whose son is he?”

I always enjoyed watching groups of Fascist students demonstrate against the United States. I would stand across the street as they shouted, “Down with the U.S.,” and return their wave as they finished. Then they would walk off, having done their duty for that day. Not surprisingly, I received an anxious letter from my mother. “The papers here say there is rioting in Rome against American students. Are you safe?” Writing back, I assured her that there was no cause for worry.

Mussolini did know how to curry favor with Catholics. He destroyed the power of the Masons, restored crucifixes to Italian classrooms, and agreed to pay the salaries of the clergy.

Yet even Mussolini could not dim my enthusiasm about being in Rome and St. Peter’s Basilica. In my seminary days, the papal Masses were resplendent affairs, the pope being carried into St. Peter’s in the richly adorned sedia gestatoria, or portable throne, always to an avalanche of excited clapping and yelling from the assembled congregation.

And the beatification Masses raised the excitement level a notch higher. At one of my first, I was standing next to a group of Austrian nuns. As Pope Pius XI was carried in, they flew into a fury of excitement and joy. Unfortunately, however, their view of the Pope was partially blocked by several tall men standing along the aisle. Desperate, one tiny Sister spied me and marched right up: “Pick me up!” she demanded. Dumbfounded, I didn’t immediately react. “Pick me up!” she firmly repeated, grabbing my arm. Obeying orders, I did as I was told, discovering, much to my chagrin, that the little nun was not so little in gerth. Still unable to satisfactorily see the Pope, she yelled again, “Higher!” Exerting myself to the max, I finally managed to raise her a few inches higher, whereupon, applauding loudly, she screamed like a Beatles fan: “Viva il Papa!” and crossed herself as the Pope extended his blessing to the nearby crowd. At that point, I dropped her. As she half smiled in thanks, I quickly and prudently moved a safe distance from the Sisters. As I soon learned, when it comes to St. Peter’s, expect anything, especially the odd, sometimes hilarious question. One day, standing in the Piazza San Pietro, I was approached by a stylish American woman. “Which denomination,” she asked, “owns that church?” My answer was most polite.

Pope Pius XI and Pope Pius XII

I shall never forget the “audience” that Pope Pius XI granted the seminarians from the Archdiocese of Baltimore. Making his five-year report to the Holy Father, Archbishop Michael Curley of Baltimore asked that the seminarians from his city be allowed to see the Pope and receive his blessing. Gathering in the anteroom of the Pope’s office while the Archbishop gave his report, the door suddenly opened and we were allowed to enter. Upon entering, we knelt in response to the order of the Archbishop, who asked the Pope to give us a blessing — which he did along with a medal for each of us. Arising, we departed, awash in gratitude.

The rector of the North American College, Bishop Ralph Hayes, always understood that seminarians were in Rome to profit from all these opportunities. As a result, we were able to attend the funeral of Pope Pius XI in February 1939 and the election of Cardinal Pacelli as Pius XII. The change in pontificates began one morning before Mass with the simple announcement by our spiritual director, Monsignor Fitzgerald, that the Pope had died. (In Rome, His Holiness is always well until the moment he dies.) During each day of the conclave to elect a new Pope, we raced to St. Peter’s, watching for the “white smoke” from the burning ballots signifying a completed election. Since the Cardinal electors indignantly rejected the Nazi threats to harm the Church if Cardinal Pacelli got in, the election of Pope Pius XII was very quick. And, of course, they voted him in largely because, having been a nuncio in Germany, the Cardinal was famous for his opposition to Hitler.

When it came to announcing the results, however, there was a glitch. When one of the cardinals, in an operatic voice boomed out: “I announce to you a great joy. We have a Pope, Cardinal Eugene …” a burst of thunderous applause broke out among a group of French students and visitors, who, standing in St. Peter’s Square, were convinced that their famous French Cardinal Eugene Tisserant had gotten the bid. Pausing until silence returned, the Cardinal continued, “… Pacelli, who has taken the name Pius XII” eliciting even more raucus cheers from the Italians. As Americans, we felt that a friend had been elected. Cardinal Pacelli had not only visited the United States, but had held an important meeting and dinner at the North American College with the Under-Secretary of State of the United States in a last-ditch effort of the United States and the Vatican to avert the coming World War. That night at the College, there was celebrating indeed.

In the summer of 1939, with war inevitable, my folks did not make the trip to Europe. But free for the summer, I was determined to see Budapest, whose national feast day was reputed to be the most beautiful of any national celebrations in Europe. The only difficulty was the date — August 20 — by which time the trip could be too dangerous. Undaunted, I enlisted my intrepid classmate Butch Burke, from a Kansas diocese, to accompany me to Budapest.

During the train ride, I was seated next to an elderly lady loaded down with an abundance of packages and baggage. Arriving in Budapest, I helped her with her belongings. When it became apparent that she had no money for a taxi, I gave her enough to take care of the fare. She then drew me aside. “Are you really an American?” she asked. I showed her my passport. “All right,” she said. “You did me a big favor. I’ll do one for you. I am fleeing from Germany, where I saw railroad cars full of our troops going to the Polish border. The war will start in a few days. If you’re here for the holiday celebration, get out as soon as it’s over, get out of here. Go to the west, anywhere in the west. But leave.”

When I told Butch about our conversation, he wasn’t impressed. Armed with the name of a modest hotel, we went to register, learning that the heart of the celebration, a big parade, was scheduled for that afternoon. It did not disappoint. The parade and its attendant festivities were grand and gorgeous. The relics, including the royal crown and the remains of King Stephen, who led the Hungarian conversion to the Church, were carried in procession, followed by the Regent and the Cardinal in his flowing robes.

Adding to the spectacle were detachments of the Hungarian military, each representing an epoch in the history of Hungary, beginning with the soldiers of the time of King Stephen. That gave a unique splendor to the event. They were followed by peasant representatives of the various regions of Hungary, each with the brilliant and varied colors of their festive costumes.

Mindful of the elderly woman’s admonition to leave Budapest, we spent just one night in our hotel before Butch returned to Rome and I headed for Paris the next morning. I figured if I was in Paris when the war started, I would be able to secure a boat ticket back to the United States or get back to Rome if the war did not disrupt the college program.

My route to Paris was via Munich. When the train pulled into Munich on the way to France, a large agitated crowd was milling around the station. As I looked out the window from the train, an excited German, sizing me up as an American, rushed over to me and shoved a copy of a newspaper, the Voelkischer Beobachter, into my hands. The headline read: “Germany signs an agreement with Soviet Russia.” “This very same newspaper reported yesterday that Germany was condemning the Communists,” he said, “How can this new headline be true?” Of course, I had no answer, only a better understanding of Nazi perfidy. After a four hour delay in Munich, we left for Paris.

The City of Light was grim, quiet, and uneasy. At the office of American Express only three customers were ahead of me. By the time I got to the teller my remaining German marks had dropped by 50 percent.

Blitzkrieg

On September 1, the Nazi blitzkrieg hit Poland. For safety reasons, I decided to return to Rome via Switzerland where, along with another student, Henry Cosgrove, I decided to climb the Matterhorn. Though the day was gorgeous, “very unusual weather,” they said, its beauty waned when, hiking up the mountainside, we encountered Swiss troops walking to machine gun emplacements on the mountainside.

Back in Rome, the city was feverish with expectation. Everyone in Italy was delighted that the terms of the Axis agreement did not require Italy to go to war. For its part, gallant Poland immediately rejected the Nazi ultimatum, the only European country to do so sans hesitation; ultimately Poland was overpowered and divided up between Germany and Russia. Thus began the year of the “phony” war — “No action on the Western Front.”

As the 1939 academic year approached, my focus was more on my upcoming ordination to the priesthood than world peace. In the vortex of excitement about war, the twelve members of my class and I prepared diligently for our December ordination in the chapel of the North American College.

None of us, truthfully, found the situation that troubling. To live in Rome, even during a War, is to live in the company of saints. Our daily walks took us to churches dedicated to heros of Christ who literally lived the phrase of St. Paul: “It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me” (Gal 2:19). The lives of saints’ mirroring the troubles of all humans, are often characterized by family turmoil, hatred or conflict. Recalling them we were consoled and directed.

Since every church is also a temple of Christ, whose Presence in the Blessed Sacrament in the tabernacle is the center of, and reason for, its existence, so every visit was also its own sermon on the Presence of Christ, brought to that altar by the Mass. Therefore, the focal point of our visits was the recitation of prayers, spontaneous or traditional, directed to Christ the High Priest.

A few yards away from the College, an added source of inspiration, was a Perpetual Adoration chapel where two Sisters consecrated every moment of the day to Christ with prayers and dedication. To avoid any distraction the Sisters wore slippers. “They come in and out like snowflakes,”as someone said. Frequently during those days I slipped into the chapel to add my personal intentions. In retrospect, the beginning of the war was the best preparation we could receive for our ordination and service in the priesthood. In fact, every event of the War was a source of spiritual education. Even now, I recall the succinct, three-word opinion of an old, Italian priest during speculation about Hitler’s designs on conquest: “Superbia semper ascendit” (“Pride always increases or expands.”) He was correct. Neville Chamberlain had no clue.

Since the U.S. State Department decreed that it would issue no visitor visas, travel to Italy was now impossible. This prevented any of my relatives from attending the ordination. We neither mailed invitations nor made plans for a party. Our focus was singular — ordination to the priesthood of Christ to be given by the Rector in the venerable chapel of the College.

Ordination Day

Ordination was conferred on December 8, 1939, the Feast of the Immaculate Conception. It was the beginning of a new life. The words of the famous hymn, “You are a priest forever” (Tues sacerdos in aeternum), sung beautifully, expressed the whole transcendent reality.

Only one outsider managed to find her way into the ordination Mass, a disturbed but gentle woman known as “The Abbess.” A convert from Richmond, Virginia, whose wealthy family allowed her to stay in Rome, she frequently wandered in and out of the chapel. Following the ceremony, the newly ordained priests gathered in a room at the College for a reception, where we entertained friends and classmates from the Gregorian University. Kneeling for a blessing, they then rose to receive the most prized gift that we could impart at the time — a cigarette.

I celebrated my first Mass on December 9, 1939, in the Greek Chapel of the Catacombs of St. Callistus, which I had discovered during one of my early walking tours of Rome. The oldest picture of the Mass in the Greek Chapel — all the inscriptions are in Greek — illustrates the Eucharistic celebration being offered at a table with the patron, a woman, seated next to the celebrant. It reminded me of an old, respected family picture, and I came to think of the people in it as my nameless, saintly ancestors. Consequently, celebrating my first Mass there was both thrilling and humbling. Today, that is no longer allowed. In fact, I was turned down, to my great disappointment, when I pleaded with the Benedictine Sisters, the caretakers of the Catacombs of St. Callistus, to celebrate Mass there during my 60th year of ordination in 1999.

On the occasion of that first Mass, I wrote this poem.

First Mass

By Father Philip M. Hannan

Rome, December 1939

Boyhood dreams of long ago saw an altar fair consecrated, trembling hands lifted there in prayer.

And those dreams have led me on dreamlike though they seemed. Now, dear friends, thank God with me, I am what I dreamed.

Other dreams have I today, brighten spite of fears that this human heart may be Christ-like thru the years.

Think of me when on your knees that this dream comes true, bowed before that altar fair, there I’ll think of you.

On December 10, 1939, I celebrated my second Mass at a side altar of St. Peter’s Basilica. St. Peter’s is the heart of the Church, and there could be no more appropriate place for a priest to consecrate the Eucharist. My third Mass was at the Basilica of St. Mary Major, the oldest and greatest church in Rome dedicated to the Blessed Mother, built in 432. What is believed to be relics from the crib of Christ rest under the high altar. The ceiling of this magnificent church is decorated with the gold Christopher Columbus brought back from the New World.

After Mass and breakfast each day, we went to the Greg for the remaining classes of those days. We were ordained for a purpose, and nothing was allowed to infringe on that purpose. Ordinations for our class were held in two sections — one on December 8 and the other early in the next year. In subsequent years I have often thought about the grim circumstances of our ordination and the remarks that it was “a shame” to have such war-time deprivations. But, I have always come to the same conclusion — the whole class consisted of thirty-seven students, and only one of them left the ministry of the priesthood; that one student received a dispensation and has led a very Christian life. That record speaks for itself.

The dignity of the priesthood certainly resulted in our being more attentive in class, and, for me, it was the best scholastic year of my life. We remained at the College for another semester to complete our theological studies. Somehow I contracted rheumatism for two weeks in April 1940, and I was so sick the doctor came to pay me several visits. His prescription was one for the ages: I was to drink red wine, and not only that, I had to make sure I heated it up first. When the pain increased, I increased the level of the red wine “cure,” but to no avail. The rector decided I should be admitted to the hospital, staffed by the Irish “Blue Nuns,” aptly named for the color of their habit.

The Sisters were very supportive, but they put me on a no-salt starvation diet, and I was getting weaker by the day. Finally, the doctor, accompanied by the Sister Superior of the hospital, came to my room and solemnly told me I must resign myself to the prospect of not being able to walk for two years. The diet had no effect except to make me very hungry. The pain increased to the point of affecting even my eyes, so the electric lights in the room were turned off and a candle with a shade was installed. A few nights later, I felt the pain spike noticeably, and it seemed to be gradually approaching my heart. I prayed very intently. Before morning, the pain began to subside from my heart, and I was convinced I was on the mend. Now I uttered some prayers of very deep gratitude.

Convinced that my salt-free diet was useless, I arranged for one of my classmates, Henry Cosgrove, to come to the infirmary with several bananas. Henry performed like a true secret agent, stashing the bananas beneath his cassock. When he gave them to me I voraciously wolfed a few down and saved some for later. “But you’ve got to help me get rid of the evidence,” I told him. “Before you go, open the window.” Even though I was still too weak to get out of bed, my baseball arm was equal to the task — I threw every peel out of the window onto the lawn below. As soon as I ate the bananas, I felt very invigorated. Even though the doctor had said I would collapse if I tried to get out of bed, I began walking around just fine.

The next day when the doctor came to see me, I told him I was feeling great and I showed him so by walking around the bed. He said simply, “It’s a miracle!” When I told him I didn’t really think it was a miracle, he replied, “It is a miracle. You’ve got to believe that, and if you don’t, you’re a bad priest.” He was implying that I wasn’t thankful for what God had done to heal me. Just then the gardener came into the infirmary in a white-hot rage and said, “I clean this place up every day, and now I’m picking up banana peels on the lawn. It’s coming from a room near here.” By that time I put on my overcoat and told the sister who was the floor nurse, “Sister, it’s time for me to go back to the seminary.”

Weak from the ordeal, I got permission from the Rector to take a week of convalescence in Sicily. I went to a good pensione in Taormina, with its dramatic setting on the sea and directly in front of snow-capped Mount Etna. The homegrown food was even better than the bananas, and I recovered fully.

Incidentally, upon returning to the United States, I asked my doctor-brother Frank to examine me, and I told him the whole story. After a thorough exam, he said, “I can’t find a thing wrong with your heart. I don’t know if it was a miracle or a bad diagnosis. Anyway, be grateful to God for the cure.” I agreed.

In the hectic first year after the conquest of Poland, Myron C. Taylor, President Roosevelt’s personal representative to the Vatican, hosted a special banquet at the North American College at which there were several special guests, including United States Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles and a representative of the Holy Father. There were various rumors about the nature of the event, and later it was learned that it was a last-ditch effort by the Pope to end the war.

It was obvious from the very animated conversation among the special guests, who disregarded their food, that some unusual proposal was being discussed. No explanation was ever offered about the nature of the banquet meeting, but eventually it became known that the papal entreaties were in vain. The reason given for the unusual site of the meeting was that the College was neutral territory, neither Italian nor Vatican.

I stayed in Rome until May 1940. The last few weeks of class were very hectic. Rumors circulated of a new campaign by the Nazi forces to increase the military tension, and I studied mightily to pass my forthcoming exams for my licentiate in theology. The Nazis finally opened their Blitzkrieg against Belgium and France, to the dismay and shock of the rest of Europe.

At that point, Secretary of State Cordell Hull had notified everyone that the United States could no longer guarantee the safety of its citizens in Italy after June 1940, and he gave a final, stern warning to leave the country. Exams were hurriedly prepared. Bishop Hayes, the rector, had anticipated this emergency and had been gathering cash to help any seminarians who didn’t have the money on hand to secure boat passage back to America on the S.S. Manhattan. Italy was desperate for American currency, and even those seminarians who had bought their tickets with Italian lira were told they had to buy new tickets with American dollars. This gave me a problem. I had received a $50 gold piece at the time of my ordination from a member of our family. Now I had to dispose of it, and so I went to the bank, presented it to the teller, who immediately bounced out of his chair and took it to the manager’s office. The manager came out and locked the door of the bank. It was illegal in Italy to hoard gold coins. Nevertheless, the manager was delighted to arrange an exchange and did so. I received for the gold piece $500 in Italian currency.

I believe the vice rector may have stayed behind temporarily at the College to keep an eye on the building. But after war broke out officially, the Italians converted the seminary into an orphanage, which I was finally able to visit toward the end of the war in 1944.

The only difficulty in the College’s evacuation plans involved an Italian-American seminarian born of Italian parents in Italy. The Italian authorities had sent him a notice that he should report for military service, which, of course, he had no intention of doing. The only alternative was to sneak him onto our boat in Genoa, the S.S. Manhattan. Practically the whole college got on that boat. We stayed in a tightly packed group and gave our tickets to the boarding agent, and he did not hold us up to find out where the tickets had come from. The students, priests, and seminarians all slept in the main ballroom, which was converted into a dormitory. The boat was filled with passengers. The transatlantic voyage was uneventful except for the lurking presence of a German submarine that tailed the Manhattan the entire way, leaving us only when we entered the coastal waters of the United States. If the United States had declared war on Germany, the German submarine, under the laws of naval warfare, could have seized our ship. An American woman passenger expressed the sentiments of many on board the Manhattan: “It’s a bit uncomfortable to have so many seminarians aboard, but maybe their prayers will guard us.”

As the Manhattan passed the Statue of Liberty in New York harbor, all the refugees knelt on the deck in prayer to thank God for the safe passage. My parents had been extremely concerned about my safety. No matter how much I had reassured them I was okay, they were getting a different story in the local newspapers, so, of course, they were beside themselves. But my arrival set their minds at ease. My parents and my brother Tom met me at the dock in New York, and we had a tearful reunion. When I later met my youngest brother, Jerry, at Union Station in Washington, D.C., I didn’t recognize him. When I left, he was four or five inches shorter than I; now he was several inches taller!

In New York I prayed with the passengers for the many blessings that God had showered me with over the previous four years — the blessing of my studies in Rome, a growing realization of the freedom and opportunities I had been given to serve God, and the inestimable gift of the priesthood of Jesus Christ.

My life was a gift! My four years in Rome constituted a four-year retreat in preparation for the priesthood, and now I was being called to begin that ministry for God’s people in my home country. Father Jean Baptiste Lacordaire, a nineteenth century French Dominican, summed up my feelings as I embarked on my priesthood in America:

To live in the midst of the world without wishing its pleasures; to be a member of each family, yet belonging to none; to share all sufferings; to penetrate all secrets; to heal all wounds; to go from men to God and offer Him their prayers; to return from God to men to bring pardon and hope; to have a heart of fire for charity and a heart of bronze for chastity; to teach and to pardon; console and bless always. My God, what a life! And it is yours, O Priest of Jesus Christ!

What a supreme gift!

I was also convinced America would be drawn into international conflict. I hoped that I, who had seen some of the terrible sources of the war, would someday be able to serve as a chaplain for our troops, preferably in combat, where chaplains are needed the most.