Читать книгу The Archbishop Wore Combat Boots - Nancy A. Collins - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 5

My First Parish Assignment

As much as I longed to see combat, I first needed to get my clerical feet wet back home. Just before I returned to the United States, Baltimore Archbishop Michael Curley came to Rome to meet with his priests and seminarians studying at the North American College.

“Just because I know your father, don’t expect any favors,” the Archbishop warned me. His bluntness dashed any hopes of requesting an assignment to a predominantly African-American parish, a desire born out of my father’s struggle for equal rights which had instilled in me a love for African-American Catholics. Growing up in Washington, D.C., I knew, firsthand, the terrible history of the Catholic Church as it related to slavery. In southern Maryland, during the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries, the Jesuits owned thousands of acres and hundreds of slaves, with those who ran the parishes selling slaves and breaking up families, a historical stain on the Church that I can never forget. (This is one of the reasons, in fact, that I have been particularly sensitive to the needs of African-American Catholics throughout my entire priesthood — a wrong, I am happy to say, with God’s grace, that I was able to address in a small way as Archbishop of New Orleans.)

Determined to do my best wherever I landed, I was very pleased when I found out that I had been appointed an assistant to the pastor of St. Thomas Aquinas Parish in the Hampden area of Baltimore, effective ten days after returning to the United States. Knowing nothing about Baltimore, much less St. Thomas Aquinas Parish, I, nevertheless, trusted that God was sending me exactly where I needed to be. As indeed He did.

My ten-day vacation allowed me to celebrate my first Mass in my own parish of St. Matthew’s in Washington, D.C. My family and fellow parishioners, forgetting that I had been doing this since my ordination six months prior, were awed that the “new priest” was so relaxed and calm. What those present that day did not see were my intensely profound, if hidden, feelings — that I, a former altar boy, was now being served at the altar by two of my brothers in the presence of the whole family, a truly overwhelming experience. Afterward, at a cheerful family reunion and party at Norbeck farm, my future pastor in Baltimore, Father Francis D. McGraw, surprised me by showing up.

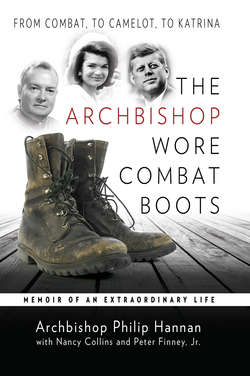

Rev. Philip M. Hannan blessing a seminarian after his ordination to the priesthood

St. Thomas Aquinas Parish

After a hurried round of visits to relatives where I was inevitably asked my opinion of the war, I reported to Baltimore and the rectory of St. Thomas Aquinas, located at 37th and Hickory Streets, and founded in 1837 by Father Thomas Foley, whose patron saint was St. Thomas Aquinas. The plain, well-built, gothic-style church, surprisingly large for a neighborhood full of Methodists, boasted an ample rectory as modestly furnished as a monastery. The sitting room of my suite consisted of two straight-backed chairs, with a third in the adjoining bedroom, whose bathroom I shared with the other assistant, Father Herb Howley, who informed me forthwith that Father McGraw, a pious, simple priest, harbored a secret — a nickname, that is, of “Muggsy,” a moniker of unknown origin never to be used in his presence. Though spare, my new digs were a veritable Taj Mahal compared to my room in Rome.

Once ensconced at St. Thomas Aquinas, it became clear that Father McGraw’s main worry was the $40,000 still owed on the new parish school building. Though a monstrous sum to him, it wasn’t to me since the weekly collection averaged around $1,000. Still, almost as soon as welcoming me to the rectory, I was informed that I would be in charge of the annual drive to retire said debt, as there was obvious tension between the pastor and first assistant, Father Howley, a sociable, carefree sort who loved to entertain with his splendid baritone voice. Though he had tried to smooth his relationship with the pastor, it hadn’t worked out.

Dealing with difficult personalities in, and out, of the priesthood is an essential part of the life, the sacrifice you make. The good Lord gives no assurances that upon ordination you will be serving with consistently pleasant people. And though I got along well with both men, the pastor was admittedly a worrier, overly devoted to schedules like our written-in-stone evening routine. Every night, following dinner, we would adjourn to the second floor, listen to the news on the radio, and the minute it ended, go downstairs to take care of requests from the people. (I was also assigned to celebrate the 6:00 a.m. daily Mass.)

The first time that I celebrated a Sunday Mass there, I was surprised when parishioners unable to secure a seat simply walked into the sanctuary and stood for the duration of the service. They, in turn, were equally stunned when this upstart, new assistant from Rome delivered a short homily on the need for charity in every aspect of our lives, including toward other nations. After Mass, the senior altar boy, a bright-looking lad of fifteen, made me chuckle when he asked where, being Roman, I had learned English.

The next day, after the collection was counted, Father McGraw asked that I accompany him to the bank. “Since the parish is big, you’ll need a car,” he announced, adding that despite its size, the percentage of Catholics was small. “We have a lot of Ku Klux Klan in this area,” he nonchalantly added, “but they don’t cause us any trouble.”

Hearing that I needed an automobile, I called my father who knew of a convent selling a secondhand Dodge, which I promptly bought. Driving around with Father McGraw, he explained that the parish was divided into three distinct sections: Hampden, Woodbury, and Roland Park, home to many of Maryland’s first families who opted to attend Mass downtown at the Jesuit church, St. Ignatius, rather than St. Thomas Aquinas in middle-class Hampden. For their part, Hampden residents were devoted to their area, as I later discovered visiting a sick policeman at Mercy, who was born in Hampden and said it was “the first time in my life that I’ve been out of it for more than a week. I’m lonesome.”

“Well, thank God that you had the good fortune to live here so long,” I responded. “Offer up your loneliness and tell your wife how much you miss her.”

In Roland Park, meanwhile, with grand St. Mary’s Seminary as well as the Anglican church, St. David’s, religious boundaries were often ignored among friends. Being introduced to one family guaranteed entrèe to all, as I found out when the MacSherrys, one of the oldest, most devout Roland Park families, invited me to dinner, introducing me to their group, including the Shriver family, whose cousin Sarge married John Kennedy’s sister, Eunice. (Favorites of Cardinal James Gibbons, the legendary Catholic prelate, Mrs. MacSherry was the only female that the cardinal let drive him around in a car.)

Unlike many Roland Park residents, the MacSherrys chose to attend St. Thomas Aquinas, and it was through them that I ended up regularly taking Holy Communion to Mrs. Shriver, who was infirm. Meeting me at the door, Mrs. Shriver’s maid, bearing a lighted candle and walking backward, so as not to turn her back on the Blessed Sacrament, would dutifully lead me to Mrs. Shriver’s bedroom. (Later, in Washington, I jokingly told Sarge that I expected the same devotion from him as from his Maryland relatives.)

Woodbury, meanwhile, site of the mills making cotton duck (a Fabric) for the war effort, was the poorest section, where I was thrilled to begin my work — and learning curve. When I hit the ground in Maryland, being a priest was far more theoretical than practical. Though the fortunate recipient of brilliant academic preparation on the subject of a vocation, I knew little about the day-to-day, person-to-person, soul-to-soul work of helping other human beings walk in the grace of God. Knowing the Scriptures by heart means nothing if you cannot make them live in the hearts of others. For someone like myself, who had grown up schooled, trained, and loved by devoted Catholic parents as well as the Catholic Church, believing in its teachings — indeed believing in God — was like breathing: automatic, life-giving, trusted. If I worked hard, perhaps I could help others find their own spiritual confidence.

Parish Census

My initial duties in Woodbury would be to help take the census that the parish was conducting as well as contacting couples who were invalidly married. (More than a hundred families, of the four hundred registered on our books, were not in a valid marriage. And, of all the evangelizing missions given me by Father McGraw, this would be my most beneficial pastoral opportunity, particularly in terms of own my spiritual development.)

On both counts, I was complimented that my first efforts would be among our poorest parishioners — many from Appalachia. Though not always Catholics, they welcomed advice and help from anyone offering, including a Catholic priest. Shortly after arriving, a tall, strongly built Appalachian man asked to speak with me at the rectory. After an awkward beginning, a surfeit of missing teeth impairing his speech, he asked me to convince his wife to return to him, giving the address of a married daughter with whom he thought she was staying.

Imbued with optimism, I arrived at the door early the next morning to a curt reception. “I don’t know where my mother is,” a young woman scowled, as I heard a scurrying noise upstairs. “Well, your father,” I said, raising my voice, “wishes your mother to return to their home. I can guarantee you that he will neither bite nor harm her.” Suddenly, a woman appeared at the head of the stairs. “How do you know that?” she asked. “Because he has lost his teeth,” I replied. The wife wound up returning to her husband.

With their open, guileless manner, the people in Woodbury soon made me feel at home as I trudged door to door asking them personal questions about their lives for the census. For the new guy in town the assignment turned out to be a wonderfully unexpected shortcut to becoming known among my new parishioners. A priest’s most important task is to know the spiritual needs of his parishioners, which requires getting out among them. You learn how to be a priest by doing the work of one — most importantly, listening. And census-taking ended up being just the spiritual-engagement short course needed by this rookie. To get to their heart, you must (first) get through their door. And humor helped. One elderly lady, asked her age, responded: “Like the hills, I have no age.” “So shall I write down ‘old as the hills’?” Suppressing a giggle, she asked me in.

Of course Woodbury also had its share of tough customers. Walking up the stairs at one modest house, I thought I saw a pair of eyes watching me. After I knocked, a gruff, unkempt man answered the door. “Get out of here. If you don’t, I’ll knock you down the stairs.” “Listen, mister,” I replied, “I’ll leave, but I guarantee that you’re not going to knock me down.” Later, when he was visited by the FBI, I learned that the man had been harboring an escaped convicted murderer.

Meanwhile, following up with the unmarried parishioners turned out to be a delicate task indeed. Any success that I might have had in helping couples depended on making friends with them first. In those days, most wives, being homemakers, were at home during the day, which meant talking to them before meeting their husbands. In this regard, children were my greatest allies.

“Mom, the priest is here,” invariably signaled a mother’s headlong rush to the parlor before their kid could blab every family secret crammed in his little head to a priest. However, once Johnny had been sent from the room, talking about him was always a conversation starter. Whatever the state of her own immortal soul, a mother was always anxious about the spiritual and physical development of her child, providing the perfect opening to inquire about the spiritual status of the couple.

It didn’t take long to figure out that when it came to getting married, women were the prime movers. (Times haven’t changed!) Men, on the other hand, were procrastinators. “All right,” the husband would say. “We’ll fix it sometime. But what’s the rush?”

With women, you could appeal to their conscience. With men, you appealed to, well, whatever got their attention. Approaching the home of one couple, I purposefully started chatting with a neighbor standing in her yard. It wasn’t long before the man in question came out of his house and joined us, eventually inviting me in to see the weight room where he and his four sons engaged in weightlifting — a sport holding zero interest for me. After several minutes of demonstrating how to bench-press two hundred fifty pounds, he looked at me and said: “You know, we don’t have any religious beliefs in this family. Maybe we ought to talk about that.” We did. And, eventually, he, his wife, and their four buff sons joined the Church.

Roland Park Catholics weren’t always so hospitable. Hearing from a Catholic friend that his neighbor’s wife was gravely ill, I made a house call, bringing the holy oils. At the door, her husband was matter-of-fact. “Thank you, Father, for coming, but we have called a Jesuit priest,” he said without inviting me in to bless his wife.

That evening, at dinner, I told the story to Father McGraw, who became uncharacteristically angry. “What did you say to him?”

“I didn’t know what to say, so I said nothing,” I replied.

“If it happens again,” he continued, “tell them that since they live in our parish, you have a duty to care for them spiritually, even if they insist on having their own priest present.” Father McGraw’s years on the job had taught him when to vent righteous “holy anger” and “moral indignation” — and when to turn the other lip, as it were. Being an effective priest takes experience — and I had none. Clearly, I had a lot to learn.

Bringing non-Catholics into the faith, of course, was always a priority. Never knowing when God was going to drop a potential believer in my path, I was always on the lookout. Serving as a substitute chaplain at Johns Hopkins Hospital, I met a young doctor who was interested in becoming Catholic. An avid, quick learner, within a week he asked to see a confessional. Surprised, I was also anxious, since he had expressed an interest in psychiatry. (Johns Hopkins had pioneered studies in the development of the science.)

Fearing he may have been influenced by anti-religious ideas perpetrated by the field’s early practitioners, I carefully explained the history and method of Confession before showing him an actual confessional. He was enthralled.

“This is the perfect way to deal with sin,” he exclaimed. “Complete anonymity. No embarrassment, and a good opportunity to instruct people. Who invented this?” His fresh observations subsequently made me reinvent my own approach to teaching converts how to confess their own lapses in judgment.

Youth Ministry

A year after my arrival at St. Thomas, it became clear to me that if we didn’t engage the young people in the parish, we would lose them. This led to one of my biggest, most successful projects. What St. Thomas Aquinas needed was a youth program geared to teenagers and those in their early twenties; but how to make it happen? And where? The only available auditorium, located in the school basement, was already reserved for the weekly Bingo Night, which is exactly where I hatched up my grand plan.

Wanting to be accessible, I made it a point to attend Bingo Nights — a cruel and unusual penance unrecorded in any spiritual text acceptable to the good Lord, who understands all the vagaries of human nature. However, compared to spending three hours answering questions — “Why are you eating so many peanuts? Don’t they feed you in the rectory?” “Peanuts help me think” — dreaming up an entire youth program was a trip to the beach.

And the peanut-thinking paid off. With Father McGraw’s permission, I investigated the interiors of the former parish school, shunted aside for our indebted newer model. Solidly constructed with classrooms, a cafeteria, and toilets, the space could handily be converted into a sizeable meeting hall. Moreover, according to my brother Tom, our pro bono contractor, a stage could also be added at the far end of the bingo hall so plays could be produced to raise funds and reduce the school debt. In short order a gang of volunteers turned our old facility into a new reality.

Figuring nothing sells like success, I asked the school’s most popular girls and boys to meet with me and figure out a program. (Naturally, the girls were the magnets.) The program we hammered out was simple and practical: every other Saturday night, we would hold a dance; and during intermission, there would be a discussion based on questions submitted by teens to what we called “The Question Box.”

To get the evenings rolling, a welcome committee of attractive, sociable teens would introduce everyone. On one point, however, I was emphatic: there were to be no wallflowers. Any girl who came had to have at least a few dances. If the boys didn’t ask on their own, I’d introduce them to the wallflowers on my own. Conversely, if a girl got “stuck” with an unattractive boy, I would swoop in and rescue her, saying I needed to see her about something. Overseeing the whole shebang would be officers, initially chosen by me, but eventually by the membership. When I presented my plan to Father McGraw, there was only one sticking point — he wanted dances to end at eleven; I, midnight. We compromised on eleven thirty.

The Youth Club was an instant hit. Kids poured in the door while the entertainment committee unearthed such impressive local talent that the Wurzburg jukebox quickly got junked in favor of a small but enthusiastic band.

But the real star of the show was “The Question Box.” Our goal was relevancy, so after starting off with a couple of basic questions about the obligation to attend Mass and confession, we quickly crossed over to discussions about the war, when I was often asked to give my own observations on the situation in Europe.

Victory breeding victory, our sought-after Saturday nights woke up the athletic committee, who formed a basketball team, drummed up donations to buy uniforms, and organized a playing schedule. The dances grew so fast, meanwhile, that, issuing ID cards, we were forced to restrict them to Catholics, prodding complaints from members who wanted to bring Protestant friends. Ultimately, we agreed that they could on the condition that they would be totally responsible for their guests. The overwhelming success of our venture proved the wisdom of the principle of subsidiarity, stressed by Pope Leo XIII in his famous encyclical on the rights of labor and the evils of industrialization, Rerum Novarum. Moreover, I learned a lot; mainly, build a field and they will come — to God.

However, when youth from Roland Park started showing up in Hampden, I knew that this newly ordained priest needed the advice and assistance of older, wiser heads. As a result, I organized a group of priests who developed an all-parish program that included a large, multi-parish ballroom dance featuring a big band at Baltimore’s biggest hotel. Ticket sales were so huge that we chartered a boat for an evening ride on the Chesapeake Bay. Acting as chaperone, Father Scalley, from St. Bridget’s Parish, merrily spent the evening prowling the dark recesses of the vessel on behalf of Christian morality.

It was our poster for that dance, a picture of the labarum of Emperor Constantine, bearing the cross with the inscription, “In this sign you will conquer,” that got me called into the chancery for a meeting with Monsignor Joseph Nelligan. Monsignor Nelligan, son of a wealthy banker, was spare, businesslike, but approachable. Allowing me to fully explain why and how I began this youth apostolate, he had just one criticism. “I support everything you’re doing,” he said, “with the exception of the poster’s cross and inscription which might be offensive to those outside our Church. It would be better to drop it.” His kindness and helpful use of authority were a great lesson, not to mention a perfect example of the wisdom of my high school teacher: “Hannan, forget every third idea.”

Capitalizing on the favorable publicity, Father McGraw gave the go-ahead for my brother Tom to build our stage in the bingo auditorium. Our first play, “Growing Pains,” pulled in over $500, then a sizeable sum and a welcome donation to the parish.

Much more importantly were the parents’ reactions to their children’s performances. Couples who had shown no interest in the Church returned with enthusiasm to the practice of their faith. Unwittingly, the kids, having become the family evangelizers, were far more effective than any priest.

“Day of Infamy”

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese suddenly attacked Pearl Harbor, reigniting my desire to be an Army chaplain. Convinced that America belonged in the war, the Pearl Harbor attack only solidified my feelings, making me even more determined to get to the front and make my own small contribution to the war against Nazism.

In Baltimore, Archbishop Curley, a supporter of President Roosevelt’s decision to join the war, announced that a priest would be permitted to become a chaplain in the armed forces if his pastor, agreeing not to expect a replacement, granted permission. It was all I needed to hear. Listening to the nightly radio reports with Father McGraw, I began remarking on the need for chaplains. Adding to the pressure, I highjacked dinner conversation, talking about the anti-Christian atrocities committed by the Nazis. Shoring up my case even further, I let my feelings be known to key parishioners who in turn talked to the pastor.

What sealed the deal, however, was the arrival of a new assistant, Father Dziwulski, replacing Father Herb Howley, who had been so kind and generous with his advice to a newcomer. Finally, biting the bullet myself, I knocked on Father McGraw’s door. Seated at his desk, he immediately knew why I was there. Almost before I could ask, he gave me his permission to leave.

When I telephoned my parents, though not wanting another son to follow my brothers Frank and Denis into the war, they raised no objection. The Youth Club and parishioners, already aware of my ambition, were comforted that a young priest was eager to serve alongside their own sons.

Registering at the recruiting office, my physical revealed no vestige of rheumatic fever damage to my heart. After getting my uniform, complete with first lieutenant’s bars and the chaplain’s cross, I was ready to go. But the Army wasn’t. Cooling my heels for several long weeks, my notice finally arrived in the mail. I was to report to the Chaplains’ School at Harvard at the end of December 1942. (The only difficulty I encountered was getting accepted by the Military Ordinariate, the Catholic diocese in charge of chaplains, since a priest, generally, had to have three years of pastoral experience before joining the armed forces. Citing that I had been ordained on December 8, 1939, I managed to qualify as a candidate by December 1942.)

The parish’s farewell party, though warm and fun, was a real tear-jerker. Held in the auditorium that I had helped build, we reminisced, laughed, and belted out the popular new Christmas song, “White Christmas.” The parishioners gave me a generous purse and a new radio to keep in touch with the news. Fighting back my own tears, I thanked them for their infinite support, inspiration, and affection during my two and a half years at St. Thomas Aquinas. Arriving as an inexperienced priest, new to their ways, their acceptance of me had nurtured my education as a parish priest. Moreover, each person’s reverence for the priesthood as well as our faith had made me realize the grandeur of my vocation. In that sense, this was a kind of graduation. Never had the words “good-bye and God’s blessings” meant more.

The following day, as he walked me to my car, Father McGraw surprised me with an unexpected question. “Will you return to St. Thomas after the war?” I paused. “I don’t think I can answer that,” I said slowly, pausing again. “I just don’t know.”