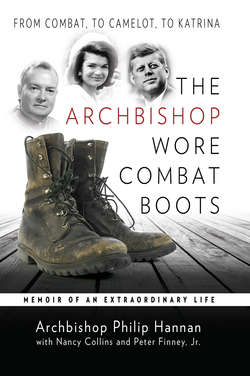

Читать книгу The Archbishop Wore Combat Boots - Nancy A. Collins - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

The Funeral of President John Fitzgerald Kennedy

November 25, 1963. As I slowly climbed the familiar steps to the elevated pulpit in the Cathedral of St. Matthew in Washington, D.C., I felt as numb and emotionally exhausted as every other American struggling to make sense of the stunningly brutal murder of the thirty-fifth President of the United States, John Fitzgerald Kennedy.

My own grieving, however, would have to wait. First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy had asked that I deliver the eulogy for her husband — and my friend. Though I had presided over hundreds of funerals in my thirty years as a priest and bishop, nothing had prepared me for today. More than a religious good-bye, this was the world’s wake, a seminal moment in American history, beamed by television to every corner of a globe still reeling in shock and disbelief. Three days earlier John Kennedy — America’s first Catholic, and, arguably, most charismatic president, a statesman of vigor, vision, virtue, and vice — had been brutally gunned down as his motorcade crawled along the cheering, crowd-lined streets of Dallas, killed by a twenty-four-year-old sharpshooter brandishing a rifle.

And though, of course, he was my President, ours had been a more personal relationship. Having met the dashing war hero and wealthy, if unknown Massachusetts congressman in the late forties, our friendship had continued into the White House where — when Catholic doctrine jousted with political instincts — I, secretly, counseled him. And now, at just forty-six, four years younger than I, he was dead from three fatal gunshots.

Taking my place behind the raised pulpit, I glanced down on his coffin, draped in the American flag, resting in the center aisle at the foot of the sanctuary. To get my bearings, I scanned the sea of black, searching for Jackie who with Bobby on one side, Ted the other, sat erect and composed, her fatigued, red eyes concealed behind a nearly opaque ebony veil. The remainder of the pew, meanwhile, was filled with sisters: Jack’s — Eunice, Jean, and Pat — as well as Jackie’s — Lee Radziwill — all so youthful it was hard to fathom that they were attending the funeral of a husband, brother, peer.

Behind the Kennedy family, a staggering array of the world’s powerful, accomplished, wealthy, famous (and not), headed up by newly sworn-in President Lyndon Johnson and his wife Lady Bird, were packed into every conceivable corner of St. Matthew’s. Rushing to Washington, they had gathered on this brilliant, sun-saturated fall day to sit in somber attendance on the lone casket in the center aisle — with the exception, that is, of French President, Charles De Gaulle. Having insisted on honoring the French tradition of standing during a Requiem Mass, the six-foot, five-inch De Gaulle loomed, a Gallic lighthouse in the storm, over those around him — ignoring FBI warnings that (due to threats on his life) he presented the perfect target for an assassin’s bullet.

To the millions transfixed on the television coverage, the seating arrangement undoubtedly seemed perfectly choreographed. But that was hardly the case. As mourners filed into the cathedral, confusion reigned. Not having buried a sitting president since Franklin Roosevelt in 1945, the woefully unprepared State Department had scrambled to stage an event of this magnitude and speed. With only three days to issue — and RSVP — invitations, the harried officials had no idea which dignitaries would actually show up, resulting in a rash of security and diplomatic faux pas — my own included. Overwhelmed, the ushers and Secret Service accidentally sat two former presidents — Harry Truman and Dwight Eisenhower — on a side, not center aisle, unable to be seen. Consequently, I left both out of my salutation.

But then, I wasn’t supposed to be standing here in the first place. Had the Kennedys followed Church protocol, it would have been the archbishop of Washington, Archbishop Patrick A. O’Boyle, not I — a chancellor serving under him — giving the eulogy. In truth, my seven years as the auxiliary bishop of the Washington Archdiocese placed me squarely on the lower end of the ecclesiastical totem pole. And, per Church hierarchy, the archbishop of Washington should have been asked to deliver the eulogy for the archdiocese’s most important Catholic. But Jackie had other ideas. Because of my long-standing, personal relationship with her husband, she sent word through Sargent Shriver, husband of Jack’s sister Eunice, that she wanted me to deliver the remarks. And it was definitely her call. Behind Jackie’s gentle, demure demeanor was a will of iron, readily enforced, if necessary, in the strongest possible terms. The First Lady wanted neither a lengthy service nor sermon — ten minutes at most. So when Sarge pointed out (during a family discussion) that, technically, it was Archbishop O’Boyle’s job, she dug in her heels.

“Absolutely not,” she snapped, dismissing his second attempt. “It’s going to be Hannan or no one. If they ask, just tell them I got hysterical and you couldn’t straighten me out.” Though incredibly honored, if flabbergasted, to learn of her decision, it put me in a real bind — immediately alleviated by the graciousness of Archbishop O’Boyle. Deep down, he must have been deeply hurt at being passed over in this sacred responsibility for his auxiliary bishop. But, if so, he shared none of his personal disappointment with me. From start to finish, he was completely noble.

As fate would have it, the Archbishop and I had been together in Rome, attending the second session of the Vatican Council, when I heard the terrible news that President Kennedy had been assassinated. As a member of the American Bishops Committee, I conducted a daily afternoon press conference, along with a panel of U.S. bishops and Church experts, for the hundreds of media covering the Council. That day, after finishing, I headed back to the Hotel Eden. Walking into the lobby, I was assaulted by the palpable rage and frustration in the air. Spotting me, an elegant Frenchman, trailed by four others, rushed up, asking in perfect English, “What does this mean? This tragedy is an outrage. Is it a Communist plot?”

“What happened?” I asked.

“President Kennedy was killed. He was shot. Did the Communists do it?” Before I could answer, a second voice piped in, and a third, all echoing the same question, same lament.

Immobilized by inertia, I could not, did not, want to believe what I was hearing. My first instinct was to deny. Surely, there had been a mistake … these people didn’t know what they were talking about! But their anger was real — and convincing. “No … no … I don’t know who did it,” I finally stammered. “As you can see, I’m coming from a session of the Council.” We stood in bewildered silence. Seconds later, as if snapping out of a trance, I suddenly became aware of other clusters of puzzled, panicked faces … the instantaneous camaraderie being forged among strangers, united by their need to know: “Who did it? Was it the Communists?”

Threading through the crowd to the reception desk, several people pulled at my cassock sleeve, saying, “Very sorry, very sorry.” Behind his desk, the clerk forked over my key in mute sympathy. Stepping into the elevator, I was alone, as other guests apparently opted to stay downstairs in the information flow. Entering my room, I saw the telephone was flashing, indicating a message was waiting. It was my brother Bill in Washington, D.C. “I guess you’ve heard the news,” he said. “Get the hell back here as soon as you can.”

Hanging up, I started to dial Archbishop O’Boyle at the Hotel Michelangelo near St. Peter’s Square, when several chambermaids, awash in tears, appeared at my half-open door. Desperate to express their astonished sorrow to the only American available, they broke down. “He was such a good man,” they cried, repeating, chant-like, Buono, buono, buono. Sobbing, they stood rooted to the spot, unable to move. It took all I had not to cry with them. “Please pray for him and his wife,” I got out before becoming overwhelmed myself. Slowly closing the door, I wept silently and alone.

Despite the jammed communications, I finally got hold of Archbishop O’Boyle, who had been trying to reach me. Assuring him that I’d get our plane tickets, I set off. The taxi driver, indeed, everyone at the travel office, posed the same questions again: “Who killed him? Wasn’t it the Communists?” (This consensus of Italian opinion was such that the Soviet embassy was forced to issue an emphatic denial of any participation.)

Fortunately, the travel office clerk was very sympathetic. Not that it mattered, frankly. Though I loathe to do so normally, in this instance I was more than willing to use whatever pull I had. Recognizing my urgency, the clerk quickly secured two tickets. Back at the hotel, I tried to telephone my rectory at St. Patrick’s Church in Washington, but the lines were solidly tied up.

Cabling notification of our arrival time, I raced to the Hotel Michelangelo where the Archbishop was in a state of total shock. Assuming the funeral would be held at St. Matthew’s Cathedral, a few blocks from the White House, Archbishop O’Boyle finally notified Sargent Shriver that we were en route. With funeral plans still being determined, Sarge said that he’d be in touch once we landed. Knowing that capable, trustworthy Sarge was our contact was a great relief. He would get things done properly with the Archbishop.

Finally, boarding a plane full of other confused foreign officials, heading to Washington for the same reason, we took off. Two Moroccans, swathed in distinctively elaborate, Middle Eastern garb, sat in front of us, while the seat across the aisle almost swallowed up the diminutive Emperor of Ethiopia, Haile Selassie. One Swiss official, part of a congregation representing Western European countries, told us that he, more or less, got ordered to make the trip. Dining in a hotel the night of the assassination, several guests had accosted him. “Why are you here?” they demanded. “Aren’t you going to Washington to represent us at the funeral of President Kennedy?”

At thirty-five thousand feet, my conversation with the Archbishop focused on Jackie and the family, whom we feared, given the brutal, public nature of Kennedy’s death, might well be inconsolable. Eventually, the Archbishop dozed off, but I couldn’t. Though physically exhausted, my adrenalized mind wouldn’t shut down. Wide eyed in the darkness of the cabin, Jack Kennedy’s Boston accent dancing in my head, I leaned back against the head rest, involuntarily rewinding the series of events that brought this extraordinary man — and his equally extraordinary wife — into my life.

Back in Washington

By the time we landed at Dulles Airport — teeming with foreign officials desperate for information — it was the evening of November 22. Spotting a particularly desolate soul, dressed in the flowing robes of a Muslim, I asked, in my halting French, if I could help. As it turned out, he had flown from Morocco with neither hotel reservations nor instructions as to the funeral’s time and place. Seeking out a U.S. representative, we discovered there were only two beleaguered, uninformed State Department officials, surrounded by indignant potentates and a gang of reporters demanding to know why things weren’t better organized. Offering to drop my new acquaintance at a hotel where he would have to fend for himself, we rounded up the Archbishop and took off.

It was around nine when we finally arrived at our rectory, much to the relief of the housekeepers and priests who had been fielding a barrage of questions. Sending them to bed, I took over. Two hours later, answering most inquiries, but barely unpacked, I got a call from Archbishop O’Boyle. His voice was tired, his words to the point: “I have been in touch with Sargent Shriver who is representing Jackie and the rest of the family in making arrangements for the funeral. Jackie wishes you to give the eulogy. Somebody will be in the sacristy at ten thirty tomorrow morning to give you material that’s to be included.” You could’ve blown me over with a feather — or less — given my exhausted state. I started to protest, but the Archbishop interrupted. “You’d better get to work.” “Of course. Thank you,” I replied. The honor at being chosen was quickly eclipsed by its reality. I had only a few hours to prepare what may well be one of the most important homilies of my life.

Fortunately, I couldn’t dwell on it. By the time I sat down to even think about what to say — much less to whom I’d be saying it — I drew an emotional blank. With everything happening so quickly, my dominant feeling was still disbelief. Moreover, I’d picked up a ferocious sinus infection. My brothers Bill and Jerry feared that whatever I said might not be understood anyway. With all these strikes against me, I’d certainly have to rely on the Holy Spirit.

Protocol demanded that a speaker, delivering a major address, acknowledge the dignitaries in their proper order. But who would be present? I certainly didn’t know, and at this hour, how could I find out? Who would have the list? From what I’d seen at the airport, even the State Department didn’t know.

The key to an effective, edifying homily is knowing your audience; only then can you come up with what they need to hear. But that intelligence wasn’t available. Surely, the fellow I was meeting in the sacristy the next morning would fill me in on everything I needed to know. “Right now, Hannan,” I thought, “the only thing you CAN control about tomorrow is what you write and say. So get going.” I started making notes, hoping that the congregation would realize I hadn’t had much time to prepare.

The first thing that came to mind was Jack’s Inaugural Address — the ideals and character espoused in those magnificent few words. But a eulogy should also speak to his distinct, powerful personality, notable to anyone who ever saw, heard, or met him — as many at the service probably had. Moreover, how could I say anything vaguely personal without divulging that I was a close friend, known, albeit, to only a handful of insiders? Tomorrow my audience would extend far beyond the walls of St. Matthew’s Cathedral to millions of Americans as well as the citizens of over ninety countries, each seeking solace in the words of the funeral’s participants. Most importantly, I had no real idea what Jackie and the family expected.

By midnight, it was clear that I simply wouldn’t have time to come up with a good, lengthy sermon. So I returned to my original notion: let the president speak for himself, in his own stirring words: the Inaugural Address of January 20, 1961. On the day ending his presidency forever, I would cite passages from the day it had begun. Lyndon Johnson may have taken the oath, but to everyone else in that Cathedral, John Kennedy was still the President of the United States — at least for a few more hours. Since I couldn’t possibly write anything better, why even try to outdo what Jack had done so brilliantly? I started scribbling notes. When I looked up it was after 1:00 a.m. If I had any hope of fighting off sinus congestion and jet lag in time for the funeral, I had to get some sleep.

At ten the next morning I walked into the controlled bedlam of St. Matthew’s Cathedral. The church, tightly cordoned off by the Secret Service, FBI, Army, and local police, prompted Father Hartman, an assistant priest at the Cathedral, to approach me at the door. “Would you please get me into the rectory?” he pleaded. “I came outside to meet someone, and the Secret Service won’t let me back because my name’s not on the list.” Vouching for my friend to the suspicious agent manning the door, we entered together. As promised, a representative of the State Department, standing in for the president’s family, showed up in the sacristy at ten thirty, carrying an envelope of scriptural quotations used by Kennedy in his recent speeches. Since the list was short, I decided to include all of them in the eulogy. But now we had a bigger problem.

Archbishop O’Boyle, Bobby Kennedy, Mrs. John F. Kennedy, and myself at Arlington National Cemetery following President John F. Kennedy’s funeral Mass.

“Where’s the list of guests for the salutation?” I asked. “Besides the Kennedy family, I don’t know who’s coming.”

The man just looked at me. “There is no list,” he said, weary and exasperated. “We’ve been overwhelmed by calls, telegrams, and questions but, frankly, we just don’t have the personnel to handle something this huge.”

“Well, do you at least know which kings and heads of state are coming?”

“No, but you’ll be standing at the cathedral door, waiting for the casket,” he replied. “The principal guests will be walking behind Jackie, so just watch and see who they are. That’s all I can say.” It was almost as shocking as hearing that I’d be delivering the eulogy! How could I ever be expected to identify kings and heads of state whom I had never met or seen? Suddenly, a trick, picked up during decades of speechmaking on the D.C. banquet circuit — that is, memorizing the State Department’s entire protocol list, delineating the rank of every member of the administration, judiciary, and Congress — popped to mind. Would that help? Probably not when it came to ascertaining the rank of kings, ambassadors, and heads of state.

Nevertheless, that was now my job. The Secret Service and FBI couldn’t help; they were too busy restricting entry into the sanctuary. The only people authorized to be admitted were Boston Cardinal Richard Cushing, principal celebrant of the Mass by virtue of his longtime association with the Kennedys; Archbishop O’Boyle; Archbishop Egidio Vagnozzi, the Apostolic Delegate of Pope John XXIII; an auxiliary bishop from New York; the master of ceremonies, Father Walter Schmitz, S.S.; the altar servers; and myself. But that wasn’t the case. Several adventurous “chaplains” attached to American Legion delegations had boldly talked their way into the sacristy — and the Secret Service wanted me to get rid of them. Extending our apologies, “so very sorry, these seats are taken,” most cooperated, especially when I herded them into pews offering a good view of the altar. However, one recalcitrant Legionnaire chaplain refused to budge. “My group paid my way from Iowa to attend this Mass,” he railed. “And they expect me to be seated in the sanctuary.” This called for the “Big Guns.” Motioning to the gray-suited Secret Service agents, I turned to our intruder. “Sorry, they’re in charge. I have no authority over them.” Faced with a god momentarily even more menacing than his own, the chaplain reluctantly capitulated.

The Secret Service had reason to be touchy. Not only had a president of the United States just been killed; but the previous day, there had been another scare during a Cathedral walk-through by FBI agents. Meticulously scouring the church’s expansive dome, they happened upon a tangle of suspicious wires with no beginning nor end. Several hours of heightened anxiety later, agents nailed the “culprits”: two mischievous Cathedral schoolboys. Happening upon the dome’s entrance and stray wire, simultaneously, the pair simply dragged it with them and left it there. (Much of the Cathedral was a security nightmare. The cavernous basement with its convoluted heating system — boilers generating hot air, delivered via pipes and floor openings — was rife with hiding places for bombs.)

With the “undocumented” visitors finally settled, we faced another dilemma: Archbishop Egidio Vagnozzi, the Apostolic Delegate of the Holy Father, had vanished. Futilely, we cased the Cathedral until the master of ceremonies signaled the approach of the official mourners. Sprinting to the front of St. Matthew’s, we slid into position to receive the body of the president of the United States. Minutes later, I caught my first heart-wrenching glimpse of the iconic panorama, forever after burned into our consciousness: the riderless black stallion … the boots slung backward … the regal, horse-drawn caisson which, having once borne the body of Abraham Lincoln, now carried the flagdraped casket of yet another slain president, John Kennedy.

Entrance card to the funeral of President Kennedy

Following closely behind, escorting their husband and brother, Jacqueline, Bobby, and Ted Kennedy led the procession of luminaries walking down Connecticut Avenue toward the Cathedral, including President Lyndon Johnson and Lady Bird, and … was it possible? … our lost Apostolic Delegate to the United States, Archbishop Vagnozzi, dressed in civilian clothes, per his contention that, as the Pope’s representative, he was ambassador as well as priest. Crowding both sides of the concourse, taking in this grave spectacle, the splendor of the fall season radiating on them, thousands of forlorn spectators, united in respectful silence, stood watching.

As this extraordinary assemblage descended on St. Matthew’s, this church where I grew up — partially funded by my Irish immigrant father, site of my own First Communion — I was suddenly awash in nostalgia, recalling my days as an altar boy for its creator, Monsignor Thomas Sim Lee, a descendant of Robert E. Lee. Determined to build, mere blocks from the White House, a Cathedral worthy of celebrating Mass for the someday first Catholic president, Monsignor Lee had done just that. And, now, that first Catholic president was being brought to his final Mass, albeit Requiem, at the Monsignor’s Cathedral. “May the good God grant,” I prayed, “that there never will be such a funeral again.”

Watching it all, I was filled with an unexpected rush of pride — and apology. As much as I’d admired and believed in my friend, I had greatly underestimated Jack’s power and influence, so evident now in the admiration and love so freely being exhibited toward this man, this President, who had touched the minds and hearts of rulers and citizens alike. But sentiment would have to step behind the task at hand; that is, memorizing the names and countries of those approaching.

In front of us, the casket, precision-lifted by representatives from each of the military services, was being carried, step by step, up to the Cathedral door and down the center aisle, the measured, military gait of the pallbearers announcing the dramatic finality of this journey. Once the coffin was securely resting near the sanctuary, Cardinal Cushing stepped forward, pronouncing the prayer for the reception of the body. As world leaders and Irish maids alike settled into their seats, Cardinal Cushing began the celebration of the Mass in ancient Latin, its sublime and sacred character so very apropos for this stellar, international congregation.

All too soon, however, it was time for the eulogy. Passing by Archbishop O’Boyle, I may have looked composed but I was not. Though humbled to be fulfilling Mrs. Kennedy’s request, I was plagued with the feeling that Archbishop O’Boyle should be ascending the pulpit stairs. Instead, it was I, by far the youngest bishop in the sanctuary, poised to address the most august audience in the history of the Cathedral at a service of unequalled drama and significance.

Prayer card from the funeral of President John F. Kennedy

The Eulogy

Once behind the pulpit, I relaxed a little. At its best, speaking from a pulpit creates unity and friendliness with those to whom you are talking. Taking a breath, I recited the salutation (per my afore-learned State Department protocol) without a hitch. Having decided to open with the President’s favorite scriptural passages, I began reading from Proverbs and the Prophet Joel which had been included in Kennedy’s dinner speech in Houston, the night before he was killed. “Your old men shall dream dreams, and your young men shall see visions…. And where there is no vision the people perish” (Joel 2:28, Prov 29:18). Moving on, I referred to the President’s speech to the United Nations on September 20, 1963: “Let us complete what we have started,” I quoted, “for as the Scriptures tell us, no man who puts his hand to the plow and looks back is fit for the kingdom of God.” It was the evocative third chapter of Ecclesiastes, however, that provoked audible sobs. “There is an appointed time for everything, and a time for every affair under the heavens,” I slowly recited, “A time to be born, and a time to die. A time to plant, and a time to uproot the plant. A time to kill, and a time to heal. A time to tear down, and a time to build. A time to weep, and a time to laugh …” But today there could be no laughter. “Oh, how our country,” I thought, “in this bleakest moment of its history, needed the spiritual solace and firm promise of that timeless wisdom.”

Original transcript of my homily for President John F. Kennedy’s funeral. Requests for copies of it came from all over the world.

Pausing, I gazed out on the sad, confused eyes staring back as I evoked the powerful words of the principal passage from President John F. Kennedy’s Inaugural Address. With its unique gravity, sacred tone, and solemn ending — a restatement of the pledge made by our forefathers — the words brought, full circle, the philosophy Kennedy had promised at the speech’s beginning. “We observe today not a victory of a party but a celebration of freedom — symbolizing an end, as well as a beginning — signifying renewal, as well as change. For I have sworn before you and Almighty God the same solemn oath our forebears prescribed nearly a century and three quarters ago.” I paused, filled with a sense of privilege to read aloud Kennedy’s iconic, final challenge on the unique responsibility of being an American. “And so, my fellow Americans, ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country. With a good conscience our only sure reward, with history the final judge of our deeds, let us go forth to lead the land we love, asking His blessing and His help but knowing that here on earth God’s work must truly be our own.”

Looking up, I saw a congregation momentarily uplifted. Having heard again their President’s visionary proclamation for our country, their faces registered both justifiable pride and reverent acceptance. Descending the pulpit stairs, I was struck by my own sense of inadequacy in the face of such a monumental occasion. However, lest I forget that this was also the funeral of an iconoclastic Irishman, I was reminded by another of the breed. Returning to my seat, I passed in front of Cardinal Cushing who, breaking the silence whispered sotto voce: “Not bad.” Jack would have loved it. (In the weeks and months afterwards, I received requests from all over the world, asking for a copy of my eulogy, which I gladly sent. Theodore Sorensen, special counsel to the President, who worked with Kennedy on the Inaugural Speech, sent an extremely thoughtful letter. “The dignity and grace of your participation in last week’s services will be remembered by many of us for a long time,” he wrote. “As you may know, I had a hand in putting together the material you read — and, while my work is not usually used by Bishops, no one could have lent it more distinction and eloquence.”)

At the end of the Mass, the pallbearers reclaimed the casket, carrying their charge, followed by Jackie, Caroline, and John-John, back out the grand doors of St. Matthew’s. As they lifted the flag-draped coffin into position on the caisson, I noticed Jackie bending down to whisper in John-John’s ear. With a slight nudge from his mother, the little boy in the blue coat tentatively stepped forward. Raising his tiny right hand to his forehead, he snapped history’s most famously poignant salute to his father. Released from restraint, the crowds erupted in an earthquake of pent-up emotion: groans, yelps, uncontrollable sobbing. Though photographers and TV cameras, naturally, zoomed in on John Jr., most missed the equally moving shot of regular human beings, disassembling in pain. Forty years later, my mental snapshot of that moment, a searing image of indescribable anguish, remains stunningly vivid.

Slowly, deliberately, the majestic funeral procession, with its Green Beret military guard, began its long, elegant procession past the thousands of bystanders packing the streets and bridge leading to Arlington National Cemetery. Reaching its final destination, the casket was lifted off the caisson by the precision-perfect American soldiers, who, in perfect lockstep, carried the casket to the mechanical platform suspended over the newly dug grave. Moments later, Cardinal Cushing stepped forward to read the prayers of interment, followed by a detachment of Irish soldiers whose stirring rendition of the traditional, “Military Salute to a Fallen Leader” harkened back to the heritage of this beloved Irish-American, himself now in the pantheon of tragedy-plagued Irish heroes.

When they were finished, Cardinal Cushing lightly touched Jackie’s arm: “Now for Bobby’s remarks,” he murmured, adhering to the funeral plans approved by the First Lady. But she didn’t budge. “No,” she said quietly, “No.” Thinking she had simply forgotten the lineup, the Cardinal repeated his verbal cue. “No,” Jackie repeated, her tone firm and irrevocable. “No. I said, ‘No.’” With unerring instinct, Jackie had correctly judged that enough had been said. Anything else would be anticlimactic. Adhering to his sister-in-law’s directive, Bobby unobtrusively slipped a piece of paper back into his suit pocket. Moving purposefully away from the others, the former First Lady walked over to the unlit Eternal Flame where, handed a torch, she reached down and ignited the flame. The impact was immediate, as a collective murmer rippled through the crowd.

After returning to her place, the Army officer in charge of the interment detail gently presented Jackie with the casket’s crisply folded American flag. Taking our cue, Cardinal Cushing, Archbishop O’Boyle, and I approached Mrs. Kennedy to offer our own final words of condolence. Exhausted, her lovely face streaked with dried tears, she, nevertheless, clasped my hand. “Thanks for the sermon,” she said. “I thought it was great.” My own swirl of emotion did not permit a response.

Offering condolences to Mrs. John F. Kennedy at her husband’s funeral

It was after five when, after dropping Cardinal Cushing and Archbishop O’Boyle off at St. Patrick’s rectory, I finally made it back to St. Matthew’s to retrieve my civilian clothes. As my limousine reached the corner of Rhode Island Avenue and 17th Street, I noticed a lone, worn-out soldier still standing duty, left behind, no doubt, by his detail leader, who had forgotten him and returned to the barracks. Quiet and dejected-looking, the soldier reflected the confused feelings and loss of innocence that many of us shared — the confused feelings of a bereaved nation. At home, I telephoned his outfit. This weary guardsman could finally stand down.

That night, slumped in my chair at the rectory, my fatigued mind tried to sort out the jumble of paradoxes, at least as I knew them, in the life and death of John Kennedy. On the one hand, he was brilliant, witty, charming, a man navigating life with the utmost confidence. Though dominating every situation, he was never domineering. On the other hand, Jack was a complicated soul, incredibly talented, yet, flawed, categorizing his actions in a manner often hurtful to those who loved him. Though he never had to worry about money, he had forged a close bond with the poor, especially poor blacks, whose love and admiration for their President was visceral and responsive, thanks to his knack for being solicitous without condescension. Handsome and virile, he was attractive to women; a symbol (by virtue of his war record) of bravery and courage to men.

Above all, Jack challenged everyone — especially the young — to be his or her best self. “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country” had called to action the children whose fathers fought and won World War II, challenging them to do something important with that hard-earned freedom. I, personally, knew scores of engineers, architects, lawyers, and plumbers who, infused with Kennedy’s optimism, went on to get a masters, doctorates — or open their own businesses. Unlike no president before him, Jack Kennedy instilled in Americans that most imperative of all things: hope.

Though I was immensely privileged to have been his trusted friend and consultant, even more meaningful was having had a priest’s relationship with the President. God knows, we didn’t always agree on religious matters. But he never tried to change or twist my decisions. Flashing back to that whirlwind presidential campaign, I smiled, recalling his long, involved questions on Church policy … my, undoubtedly, equally long-winded answers which he always accepted. We might argue like the devil but no verbal skirmish was ever disrespectful of either of our identities. Oh, how I would miss that intellectual parrying — miss my friend, Jack. (Even now, a half century later, I still marvel that God saw fit to bring John Kennedy and me into each other’s lives at that particular moment in America’s history. In the end, I have only the most inexpressible wonder and gratitude for having enjoyed such a remarkable relationship with such a remarkable man — one of America’s truly great leaders.)

The next morning, my usual ride from the rectory to the chancery presented a startling, if reassuring, example of our incredibly resilient system of government. Motoring past 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, there were no crowds, demonstrations, nor protests — merely two gardeners, raking leaves, on the White House lawn. The sight recalled the excited, worried questions that I’d encountered in Rome a few days earlier: “Is it a Communist coup?” “Will there be an attempt to overthrow the government?” Despite our national broken heart, the machinery of democracy neither fell apart nor ground to a halt, providing, instead, one of the finest hours in our national history.

Thank you note from Jacqueline B. Kennedy

Reinterment of Babies

Nine days after her husband’s funeral, I got a call from Jackie who was still living in the White House. She had decided to bring the bodies of the children whom she had lost — a stillborn daughter in 1956 and Patrick, who died three days after his birth in August of 1963 — from the Kennedy Family cemetery in Hyannis, Massachusetts, to join their father in Arlington Cemetery.

“Could you be ready on Wednesday (December 4),” she asked, “for the reinterment of the bodies of our two babies at Arlington?”

“Certainly.”

“All right,” Jackie said. “It will be very secret. An Army staff car will pick you up at the rectory. The driver will know where to take you but not why you’re there. Expect him about eight o’clock.”

Jackie was insistent that only a very small group attend the ceremony: her mother, Janet Auchincloss; sister, Lee Radziwill; and three or four other close friends. Though I thought about suggesting she increase the number, I decided against it. A larger ceremony, recalling Jack’s so-recent funeral, might be too hard on her. And, of course, I told no one, not even Archbishop O’Boyle. At the appointed hour the car arrived, and I got in with the driver. “Do you know where to take me?” “Yes sir.” Heading towards Arlington, I asked the young soldier where he was from. “I don’t like talking about it,” he replied haltingly. “I’m not proud. I’m from Dallas.”

Reaching our rendezvous, just outside the gates of Arlington Cemetery, I found Jackie, Lee, and the few friends who could fit in a limousine (Caroline and John were left back at the White House). Getting into her car, I drove with Jackie to the Kennedy plot. “Since I wanted to keep this secret,” she explained, “I’ve spread the rumor that the reinterment will be tomorrow at noon.” (Her plan worked.)

Driving as close as possible to where Jack now lay, we parked and got out. The sight of two such tiny, white caskets (holding such tiny, little bodies) was truly heart-wrenching. Before starting the ceremony, Jackie and I placed each on the ground near her husband’s fresh grave. Seeing the three — father, daughter, son — back together again, albeit in death, was a stark reminder of the Herculean effort made by their parents to bring these babies to term. Both Kennedys desperately wanted more children and, losing these dear, little ones, had only increased the value of the two who survived. Though this tender scene cried out for soliloquy — conscious of Jackie’s fragile emotional condition — I decided to offer only the prescribed, short prayers of the ceremony.

When we were finished, Jackie’s sigh was deep and audible. Turning to me, she began talking as if her life depended on it — which perhaps it did. In a little under two weeks, the world as this courageous thirty-four-year-old woman knew it had spun out of control on its axis. That she was even here tonight, able to momentarily put aside her own exquisite suffering to bring together her deceased family in their final resting place, was nothing short of a miracle. Trying to understand, to come to terms with this senseless tragedy, would take a lot of talking — and I was more than happy to listen.

Walking back to her limousine, she asked if she could have the ritual book and stole that I’d used for the service. As I gladly handed them over, they seemed to unleash a torrent of spiritual concerns that only a priest could possibly help her work through: Why had God let this happen? What could possibly be the reason? Jack had so much more to give, was just hitting his stride. What was our destiny in heaven? Did I think he was there? How would the children ever understand? What should she tell them?

Eventually the conversation turned more personal. How was she to carry on? With the public’s feelings about her, how would she ever be able to live even a semblance of a normal life? She didn’t disdain those who tried to see and touch her, as if doing so would somehow secure a souvenir of the President. She understood that she was forever destined to have to deal with public opinion, the differing, not always flattering, feelings toward her. But she did not want to be a public figure. In one pull of a trigger, her identity as both wife and First Lady had been wiped out. And though she appreciated the good will and love being lavished on her, she desperately wanted to be private, someone whose character would be shaped by herself and her family. Already, however, it was clear that the world viewed her, not as a woman, but as a symbol of its own pain, expecting her to carry a torch not of her own making.

The more she talked, the more that Jackie’s real feelings surfaced, her comments frank and to the point. Particularly galling, she confided, was the public’s surprise at her stoicism while preparing — and during — the funeral. Why had so many columnists marveled at her composure? It was the least she could do for Jack. He would have expected nothing less. Given the presence of her mother and sister, I thought it might be more appropriate if she and I, privately, continued our conversation at my rectory or the White House. But Jackie was undeterred. “I don’t like to hear people say that I am poised and maintaining a good appearance,” she said, resentfully. “I am not a movie actress. I am a Lee … of Virginia.” Just then, in a far gloaming, the imposing statue of General Robert E. Lee came into view, a fitting reminder that those with Lee’s blood in their veins did not crumble in the face of adversity.

It was a strength she would need more than ever. Jacqueline Kennedy, America’s most glamorous First Lady, was now the most famous widow — and single mother — on the planet. Yet even as she mourned the end of her old life, she was determined to be in full control of creating a new, secure one for her children and herself. Besides grappling with the death of a man whom I believe that she truly and deeply loved — who literally died in her arms, his blood and brain matter spattered on her lady-like white gloves — the sheer rawness of profound loss was finally beginning to set in.

That evening, as we strolled together through the beautiful if melancholy reality of Arlington, death was much on her mind — not only that of her husband, but also the children they had conceived, and lost, together. More urgently than ever before, any kind of afterlife — the Church’s view as well as her own — weighed heavily. Having been traumatically, involuntarily wrenched from her known reality, Jackie Kennedy was suddenly faced with the stark reality of her next chapter: Life after Jack. Life alone.

Our conversation that evening marked the beginning of many such discussions between Jackie and me. Aside from our separate, if newer relationship, her trust in me sprang from the knowledge that Jack also set store in my counsel. As a result, I was one of the few people to whom she could turn to express the desolation and despair felt over the loss of her husband. In the months following the assassination, Jackie frequently put her agony and confusion down on paper in handwritten letters. While candidly describing her tumult of emotions, her words always reconfirmed a deep love for her husband, the loneliness without him.

Moreover, they illustrate the degree to which her life had been, inextricably, intertwined with his. Jack was her future. Having never realistically visualized an existence without him, she now faced an appalling emptiness. Even more importantly, her letters present a resounding refutation of the rumors and innuendo that the marriage of John and Jacqueline Kennedy was more one of convenience than affection. That is simply not the case — which is why, after much soul searching, I have decided to include some of her correspondence in this book. In the long run, these anguished notes prove, despite opinions to the contrary, that her husband’s infidelity had not irreparably harmed their marriage, that theirs was a relationship grounded in deep, emotional conviction until the very end. Moreover, Jackie’s letters reveal a tenderness and love which, in my opinion, is almost heroic. Despite all of Jack’s faults, Jackie loved her husband — as her words prove.

Sixteen days after the interment of her children, I received this letter from Jackie, dated December 20, 1963 (original punctuation).

Dear Bishop Hannan,

I have meant to write to you for so long — to thank you for the most moving way only you could have read those words at the funeral, to thank you for the book and cloth from the children’s burial — for asking me to the December 22 Mass — for your help always to my husband in seeing the world the way he did.

If only I could believe that he could look down and see how he is missed and how nobody will ever be the same without him. But I haven’t believed in the child’s vision of heaven for a long time. There is no way now to commune with him. It will be so long before I am dead and even then I don’t know if I will be reunited with him. Even if I am I don’t think you could ever convince me that it will be the way it was while we were married here. Please forgive all this — and please don’t try to convince me just yet — I shouldn’t be writing this way.

With my deep appreciation.

Respectfully,

Jacqueline Kennedy

One of the greatest regrets of my priesthood is that, in the immediate months following the President’s assassination, I did not make even more of an effort to sit down and encourage Jackie to talk about her feelings. Given her condition, it should have been a priority. Of course, as the Auxiliary Bishop of Washington, assistant to Archbishop O’Boyle, pastor of St. Patrick’s, and editor of the archdiocesan newspaper, responsible for the weekly editorials — not to mention fielding endless phone calls about Mrs. Kennedy — my hands were incredibly full. In retrospect, however, hiring someone competent to answer those calls, I should have put those hours, instead, into listening and hearing the woman who elicited them. To my eternal regret, I neither had, nor made, enough time to provide Jackie with the spiritual direction that she needed before moving to New York.

Two weeks after the assassination, the former First Lady and her children moved out of the White House into Averell Harriman’s house on N Street in Georgetown where it became rapidly apparent that any hope of privacy for the three would be impossible. The minute the family took up residence, their home turned into a tourist attraction — buses clogging the street, cameras aimed at every window — hoping to catch a glimpse of Jackie or the children. (The only safe route, as a result, was the back door leading to the alley.) Finally, fed up with this wretched existence, Jackie decided to move to New York, where she found an apartment on 5th Avenue not far from the Convent of the Sacred Heart, where Caroline would attend school.

Very important letter from Jacqueline Kennedy expressing grief over her husband’s death

The typed note she sent, in reply to mine, describing the reasons for her move, was both poignant and sad:

July 27, 1964

Dear Bishop Hannan:

I do want to thank you for your kind letter and the knowledge that I am in your prayers is a great source of comfort to me.

The decision to leave Washington was not easy, however, I do feel it the wisest one for both my children and myself at this time.

I shall never forget all you did to help me through those first tragic days and hope I will see you again before too long.

Respectfully,

Jacqueline Kennedy

After a natural paralysis, following the death of the President, all kinds of projects were proposed to commemorate JFK. In the end, Jackie and the Kennedy family finally approved two: the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., and the Kennedy Library at Harvard University in Boston. On both projects, I was asked to be a member and, though honored, knew it impossible to be an active member on more than one. At the insistence of Polly Wiesner, a great friend of Jackie and her mother, Janet Auchincloss, I ultimately chose the Kennedy Center. Eventually, however, Polly — confiding that Jackie favored the Kennedy Library as having more educational value and staying power — asked that I try to convince her differently, as I did whenever we saw each other at meetings for the Center. (Her love for her husband compelled the former First Lady to, at least, be involved in the planning of something celebrating his accomplishments and vision.) At one such gathering, Jackie’s own sketches and watercolors of angels (demonstrating undeniable talent) were shown. Subsequently, I suggested that she design the cover for the proposed Register containing the Center’s donor names. Jackie loved the idea, promising to follow up since, as she put it, “a simple cover didn’t need a designing genius.” However, due to her other demands, Jackie’s “Memory Book” never came to fruition.

As President Kennedy’s May 29 birthday approached, Jackie decided it would be appropriate to pray for the repose of his soul at a Mass — including friends and cabinet members — at St. Matthew’s Cathedral. When she asked that I give the homily as well as celebrate the Mass, I decided on the same one I gave at the Funeral Mass on November 25, 1963. (The Knights of Columbus, meanwhile, having organized their own Memorial Mass for Jack on the same day at the Shrine of the Immaculate Conception, were hurt that no one from the Kennedy family would be present. So, at the behest of Archbishop O’Boyle, I rounded up Sarge and Eunice Shriver who showed up to save the day — and feelings — of all concerned.)

During the Cathedral Mass, Jackie was extremely emotional and teary-eyed. In fact, she was so choked up that, when I approached her to exchange the peace of Christ, she could neither speak nor shake hands. Later, in a handwritten note, she explained that being back in St. Matthew’s had simply been overwhelming.

June 1, 1964 (original punctuation):

Dear Bishop Hannan:

I do wish to thank you for the Birthday Mass — for making it so beautiful and so moving — For what you said about President Kennedy.

I am afraid that that — then hearing the Star Spangled Banner sung by the choir — were more than I could bear — and I felt as if time had rolled back 6 months — and I was in the same place in the same church I had been in in November — and all the efforts one had made since then — to climb a little bit of the way up the hill, had been for nothing — and I had rolled right back down to the bottom of the hill again.

Letter from Jacqueline Kennedy that describes her state of mind after the assassination of her husband

That is why I could not bear to look at you when you came to speak to me — as I did not think I could control my tears — but I wanted you to know that was the reason.

You must know how grateful I am to you every day — for believing in and being a friend of John Kennedy when he was alive — and for bringing meaning out of the despair at his funeral and birthday Masses — and for the night in Arlington with our two children — and for your work now at the Center. You will always be working for all the things he believes in — and I will always know that and be comforted.

I will try so hard to recover a little bit more myself — so that I can be of more use to my children — and just for the years that are left to me — though I hope they won’t be too many — And maybe one day soon I will feel strong enough to come and talk to you — With my deepest appreciation.

Respectfully,

Jacqueline Kennedy

In the years following, other than periodic Kennedy Center board meetings — I didn’t see Jackie that much which, of course, was my loss. In 1965 when the ground was finally broken for the Kennedy Center — attended by President Johnson — Bobby and Jean Kennedy Smith asked that I give the invocation. (The site, a former public golf course where my brothers and I, using tees fashioned from a handful of sand in a nearby bucket, each played for five cents, carried its own memories for me.) When the ceremony was finished, an enterprising cameraman snapped a photo of our collective profiles — Johnson, Bobby, Jean, and me — dubbing it “Profiles in Courage.” Though less interested in the Kennedy Library, I attended one meeting in New York where architect I.M. Pei presented his plans for the building. The curious ensemble of personalities included Chief Justice Earl Warren, who took great pride in protecting Jackie, as well as crude types like the Texas donor who, thrilled at being in close proximity to the former First Lady, decided to bullhorn her own pet theories on saving the country. Polite but deliberate, Jackie smoothly cut her off, eliciting such raucous applause that the woman gave up.

Groundbreaking of the Kennedy Center on December 2, 1965. A photographer snapped a picture of the profiles of Jean Ann Kennedy Smith, me, Robert Kennedy, and President Lyndon B. Johnson dubbing it “Profiles in Courage.”

Though Jackie never talked to me about her second marriage to Greek shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis in October 1968, I viewed it strictly as one of convenience. Of course, I totally disagreed with her decision (as did most of the world) which no doubt she sensed — perhaps why I wasn’t consulted. As a result, I was both surprised and deeply honored when Caroline asked that I preside over her mother’s burial following her death from cancer on May 19, 1994, at the age of sixty-four.

After her Funeral Mass at St. Ignatius Loyola Church in New York, Jackie was laid to rest next to her husband, her children, and the Eternal Flame in the Kennedy burial plot in Arlington Cemetery. (On that brutally hot day, I was the only priest in attendance.) Caroline Kennedy Schlossberg, coordinator of her mother’s last good-bye, was determined to keep reporters and photographers as far away as possible and did so — a half mile away, to be exact. Like her mother at her father’s funeral, Caroline wanted things kept short. Before we started, I noticed her looking at the interment service’s first draft, indicating that President Clinton would “address” the mourners. Scratching out “address,” she penciled in “remarks.” The last thing Caroline needed was Bill Clinton on a verbal tear. As a result, the grave-side ceremony lasted just over ten minutes: Handsome, young John Jr. read from the fourth chapter of St. Paul’s First Letter to the Thessalonians: “We would not have you ignorant, brethren, concerning those who are asleep,” he said, his voice strong, “that you may not grieve as others do who have no hope. For since we believe that Jesus died and rose again, even so, through Jesus, God will bring with him those who have fallen asleep” (verses 13-14). Caroline then followed with Psalm 121: “The Lord will keep you from all evil; he will keep your life. The Lord will keep your coming out and your coming in from this time forth and for evermore” (verses 7-8).

When Jackie’s beloved children had finished, I offered my own few words, that Jackie, “so dearly beloved, would be so sorely missed” … concluding with the prayer of committal: “O, God, the author of the unbought grace of life, you are our promised home. Lead your servant Jacqueline to that home bright with the presence of your everlasting life and love, there to join the other members of the family. Console also those who have suffered the loss of her mortal presence. Give them the grace that will strengthen the bonds of the family and of the national community. May we bear your peace to others until the day we join you and all the saints in your life of endless love and light. We ask this through Christ our Lord. Amen.”

Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis is laid to rest in 1994 (Reuters photo)

Across the Potomac, a bell tolled sixty-four times, once for each year of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis’s extraordinary life. The most famous woman in the world was then laid in her final resting place, attended by fewer than a hundred close family and friends — exactly what this private, enigmatic soul would have wished.