Читать книгу Look At Me - Nataniël - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

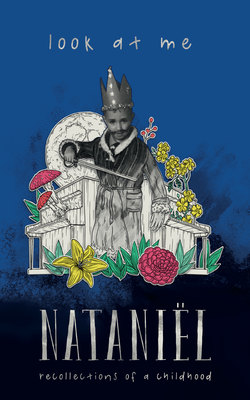

A Table for Prentjie

ОглавлениеSomewhere near the church, the main road’s tar disappeared and there, where gravel became ground, they sat in a row: church, school, tennis courts, dormitory. In this dormitory my mother worked a few times a week, she had to supervise until the sun began to set. On these days I had to stay there after school; I have no idea where my baby brother was.

A few years ago I visited the town for the first time since I left there at the age of nine. I was invited to do a show at the church hall; this hall had been a gigantic building where all of the town’s plans began or ended, but when I went back I was shocked to see how small and cramped the hall actually was. This has happened a few times: childhood buildings that had shrunk so much over the years that on a return visit they were invariably unrecognisable and always bitterly disappointing. This would also be the case with the dormitory, but for the purposes of this story I have kept it in its original form, long, pale and damning.

The occupants were farm children – the descendants of both wealthy and struggling farmers – who all went back home on Friday afternoons, city children who’d been sent there to keep out of trouble, and a few town children from families too miserable to have any future prospects. A few had to stay there over weekends and even holidays. And when my mother was on duty, I wandered about, one afternoon after another.

The youngest children played outside, the rest had to do their homework in the dining hall. I was too young for real homework and so I wandered. The front door opened onto a small entrance hall and then you could turn left or right down a long corridor with pale, polished floors and on both sides a multitude of doors. There was a forgotten lounge, an office, bedrooms for staff, single rooms and dorm rooms for pupils (I don’t know how it was decided who would sleep in a dorm room and who in a single room), bathrooms and the dining hall. At the end of the corridor, on either side there were sharp turns to even more rooms and the long wing at the back that consisted of laundry rooms, storerooms and the kitchen; from above thus a perfect 8.

Here there was no pleasure – perhaps for others, but I couldn’t find anything, not a single pretty thing, no mysterious corners or dancing shadows, only empty walls, rooms and children. And The Smell. There was an inescapable smell that would not budge for even a moment – not the smell of the cleaning products that are still so popular in shiny corridors, nor that of chicken pie baking in big ovens, nor that of coffee escaping from a staffroom; it was a dead smell, a grim grey smell. Mother was terribly upset when I once began sniffing a slice of bread in front of the other children, I couldn’t help it, I was certain The Smell hid in the thick slices of death’s bread that were slapped down each day in front of everyone. No butter or jam could disguise those dreary sponges.

Maybe it was the recipes of those years, or the fact that not every town had someone like my grandmother, but only tiredness and drabness ever came out of that big kitchen. I wanted to scream, Where are the rusks, where are the scones, where are our biscuits, we are little children! That was where I first had The Horrors, when trays with plastic containers filled with quicksand and funeral sludge were carried into the dining hall. I would wait until my mother looked away and then disappear down the corridor.

It was during one of these furious I-have-the-horrors-and-I-am-hungry strolls that I saw the door to a boy’s room was wide open. He was sitting on his bed and paging through a book. His feet were off the ground. I never knew his name, in my thoughts I called him Prentjie. He was the oldest child in the dormitory, but also the smallest; he was quiet and very beautiful, it looked as though he’d been drawn, his clothes were never dirty or wrinkled, not a single blond hair was ever out of place, he never looked for trouble and only spoke when someone asked him a question. All the children in the world should be like him. I liked him a lot.

I stood and looked at Prentjie in his barren room, not for so long that he would notice, but long enough to see there was nothing beautiful, not a rug, not a chair, only a bed and a wardrobe with a suitcase on top; the walls were empty, the only picture was Prentjie. Why wasn’t he with the others in the dining hall? Was he also escaping from The Smell? And where would he go? He only had his ugly room, I felt so sorry for him, for days I wondered what I would do if I had to live in a room without any of my things.

It was a weekday afternoon, warm, a few children played listlessly next to the dormitory, the rest sat staring at their books in the dining hall. I was in the corridor. Prentjie’s bedroom door was open. I walked closer to see. He and his book were not on the bed. But the Yellow Juffrou was on her knees next to the bed. She was one of the teachers who lived in the dormitory, youngish with short, light-yellow hair and an unusually broad face, with a dimple in each cheek that made her look like she was constantly smiling. She was the Standard Two teacher and wore a yellow cardigan every day.

In her hand was a pencil. She drew a thin horizontal line on the wall, then another one directly below the first, and connected the two at both ends. Then she drew two thin lines from the left-hand corner to the floor, and the same on the right-hand side: a table!

My mother appeared in the corridor.

Are you coming? she asked.

Her handbag hung from one arm, my brother from the other. He recognised me and laughed with an open mouth, he bent his knees and jumped up and down with his short little legs. Go home, play noisily until dinner, bath until the whole floor was under water, that’s what he waited for on dormitory days. But I didn’t feel like playing. Something was happening. What was the Yellow Juffrou doing? I knew sleep helped children grow, but I was awake the whole night.

The next day school took hours, just finish now! I stormed down the stairs, past the tennis courts, in through the dormitory’s front door, came to a stop in the entrance hall and panted, waiting for all the children to disappear into the dining hall for lunch and The Smell. I prayed Prentjie’s door would be open.

Finally. The corridor was empty. Prentjie’s door was open. Next to his bed, exactly where it had been drawn, was a table. I gasped. That was why he had his own room! That was why he was so small! That was why he didn’t speak! There was magic happening here, it was a chosen room!

But why only the table? Why not a chair? Was the Yellow Juffrou worried she would get caught? I opened my school case, I grabbed a pencil. The children didn’t eat for long, afterwards they went to their rooms to change and play before homework. Whatever was going on here, I was still sorry for Prentjie. Next to the table I drew him a chair, I drew quickly and the feet were skew, but the magic would fix them. I also drew him paintings against the wall, storybooks in a row, an extra window that overlooked a river with fish and small boats, a big potplant with finger leaves like the one on our porch, a tin of biscuits, another tin of rusks, a radio, a standing lamp, two fat cats and a bicycle. It would be a glorious room; after this Prentjie would be my friend.

Your mother is going to kill you, a voice said.

I jerked around. One of the kitchen ladies was standing in the doorway. She was the one who always sliced and stacked the smelly bread.

Who scribbles on a wall? she asked.

The Yellow Juffrou, I said.

Your mother will kill you twice, you can’t say the Yellow Juffrou!

She drew the table, and then the room made it real! I’m only drawing little things, he has nothing!

She only marked where the table should go, as an example, so the workers would know where, all the older children are getting desks next to their beds!

No!

I sobbed out loud. The kitchen lady twitched her nose.

Don’t cry, she said, They’ll hear you. We’ll get a cloth and quickly clean this up.

She turned around and disappeared.

I cried from fright and because there weren’t any miracles and because of being killed twice. And because of Prentjie who only had a table. Two kitchen ladies appeared. Each with a big cloth and a spray bottle. The first one put her hand on my head.

Go wash your face, we won’t tell a soul, she said.

I walked down the hall. I could hear them talk.

What happened here? asked the one.

The funny one wanted to do magic, said the other. His poor, poor mother.