Читать книгу Look At Me - Nataniël - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

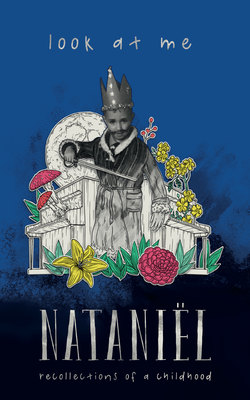

Our Fence

ОглавлениеOur World and the Whole World were separated only by silver chicken wire. The holes were big and the wire was thin, the kind that wouldn’t keep anything in or out, it was just there, stretched tightly between thin silver poles, a shoulder-high, almost invisible fence, where else should silver wire go? The fence ran along three sides of the erf, at the front by the road, on one side along the empty erf between the Gagianos and us, and on the other side alongside the vineyard that belonged to nobody. There was no fence at the back of the erf. There was a back yard with a shed full of tools, and a cement laundry block, complete with a high tap and a deep basin. Trees, some fruit-bearing and others not, stood around like creatures that were unwilling to either chat or queue. Long grass and single reed stalks showed that the erf had come to an end, here there was a small vlei, sometimes a trickle of water burbled quietly.

I never questioned the purpose of the fence, it wasn’t for safety, what danger could there be? And at the back it was unnecessary, beyond the vlei there was nothing, the Whole World ended there, as it did two streets away on the other side of town, as it did at the end of our friends’ erf downtown. (Our Whole World was called a town, there were other towns too, those existed only when we went there. The rest of the time they were their own Whole Worlds.)

On hot days I stood on the front porch and watched the fence glitter in the sun, it was a spider’s web without a fly, with a small front gate, also glittering, and a big gate for cars. The brilliant shine was because the fence had been painted, why and by whom a fence made of chicken wire had been painted was a mystery, it was covered in the shiniest paint anyone had ever seen. And it was neat. And because it was neat, nothing grew on it, not a single climber stretched out a tendril, the spider’s web hung there, empty and clean.

And here a child could do what has long since become impossible: even early in your life you could open the small gate and step into the Whole World. You could walk on your own down the road, right in the middle, traffic was scarce and it was quiet. Grandmother said you could hear a motor car the moment it left the factory, you would know when you had to make way.

The Whole World was called Riebeek-Kasteel. And when you stood at the gate and looked to your left, up the hill, you saw The Stoepsusters’ house, the stop street and the crossroad. On the other side were orchards full of shadows and a sheltered house where someone with a title lived, Reverend, Sergeant, Magistrate, the kind of man whose wife was never seen without a brooch. I liked looking to the right. There the downward slope levelled out, you could walk to the corner erf. Here I often played. I have no idea who lived there, but I knew the garden well, an exceptionally big, empty yard without a single blade of grass, only rose bushes, millions of them, in between were fountains and benches. The house was in the middle of all the roses, a long, flat house with Venetian blinds, repulsive and always shut, I can’t remember ever going inside.

When you turned right, a tennis court and an empty square were on your left, this was the centre of town. Here farmers parked their bakkies. I knew what farmers were and that they lived on farms and that their children also lived there and disappeared from the town every afternoon after school, but as long as the town was the Whole World, I didn’t feel like thinking about it or trying to understand where the farms fitted in.

As soon as the police station appeared on your right, you could turn left to the shops. This was a concoction of buildings, porches, alleys, courtyards and a few houses, all connected. First was the haberdashery, it belonged to a friendly woman, she was as thin as a rail and every day her long, pitch-black leg hair was flattened by stockings, people called it blanket legs. There was a post office and next to it an alleyway with doors to rooms where single people lived, also a back yard full of the middle shop owner’s children. I played here occasionally, but when I had 20c in my hand I walked straight into the shop. The middle shop’s inside was made of wood. Counters with glass fronts wound through the entire space and displayed the contents of their drawers. Screws, sweets, gloves, blue soap, polish, cooldrink glasses, socks, ties, toys, apricot sweets, marshmallow fish, pocketknives, nappies, fly poison, clothes pegs, tomato sauce, envelopes, writing pads, pencils, curtain hooks, hinges, sunglasses and headache powders, all in a row.

In this shop I discovered that a day without possibility, even the smallest explosion of deliciousness, was an unbearable greyness. As soon as I knew the way, I begged my mother to send me there, and she did, two or three times a week, to buy something, always two things at a time: a loaf of bread and a bottle of milk. Or a bag of tomatoes and a newspaper. Or orange squash and brown paper. Then there was 5c left over. With this I could buy myself two things: a vienna and a small bag of chips. I was a rich man’s child! Add Saturday’s hot dogs and Sunday’s pudding, and there was seldom a day without a highlight.

If you didn’t turn left at the rose garden but went straight ahead, you would walk past the small haunted house, a miniature house with boarded-up windows and a closed-off porch right on the road. There was nobody here. And nobody talked about it. Then you could turn right again, just after the tennis court and the parking place for the farmers with farms that for now were located in another world; then you were in the high street, even though the street you had just been in was called High Street.

But we carry straight on. On the next corner was a garage. Here my father worked, he was one of the town’s mechanics and could fix anything, if anything moved in town it was because of my father, everyone said he was the best in the district. What was a district? Where did a district fit in the Whole World? I never asked, it was enough that Father was the best.

Here the untarred road began, and also the hill, church, school, dormitory, all in a row. Then downhill again, then a side street to the right. Here everyone turned without looking to the left for even a moment; just before you turned, just after the empty piece of ground next to the dormitory, lived The Vuurhoutjies. Whoever thought up the word boskasie must have gone past there first. Trees like you wouldn’t see anywhere else grew there, twisted and bent in all directions, like crazy ballerinas they formed a circle around a hut of clay, stone, cement, wood and corrugated iron, not a squatter’s shack, a crooked magician’s cocoon with an appeal no one could withstand, once you looked you stopped, you were transfixed. The dirtiest family in the Whole World lived there, they were called The Vuurhoutjies because their faces were all black as soot. They did have water, also electricity, also clothes, they just didn’t feel like it. Food simmered in a pot over a fire, a goat bleated, a sheep wailed, chickens scratched, a pack of children wandered about, wrapped in blankets or tied up in towels, all with long, shaggy hair, not young children, teenagers, lovely, muscled, dirty teenagers who went to school when they felt like it, sometimes came to stand in the door during a church service, slunk around late at night, never did any harm, only prowled and growled like wolves.

Turn right, quickly turn right. Twenty steps from The Vuurhoutjies there was a big erf we often visited, here Uncle Sam and Aunt Stienie lived. Aunt Stienie was Grandmother’s sister, a tiny, sweet woman whose face I could never remember, every time my mother had to introduce her to me again. Uncle Sam was big and busy in the yard, everywhere there were piles of raw material, countless projects patiently awaited their completion. There was also gardening, rows of vegetables flourished in the sun, and chickens were slaughtered, yes, the first time I unsuspectingly stood closer when a hen was laid down on a tree stump. Here comes a trick, I thought. Long after the head was gone and the feet stopped jerking, I stood by the pile of tarred poles, throwing up and sobbing in turn.

What I do remember with pleasure is the darkness of the house, a big house with a long passage. It was a good darkness, Aunt Stienie’s victory over the heat, she could darken a room so completely with long curtains – were there shutters or blinds as well? – that I couldn’t believe the coolness. I remember one time when the house was completely silent, there was a corpse in the corner room, the hearse had to come from far away, from a place that only existed when a hearse was needed, and this was the coolest house imaginable. Was it a family member? Or just an acquaintance with nowhere else to wait? I do not know, but I do remember the peaceful occasion, calm and full of acceptance; to me it was entirely new and I liked it. It was like factory custard nowadays, deadly and delicious and nobody talks about it.

A year after my memory found me, I still don’t know how many questions each person is allowed, these conclusions are thus my own:

It doesn’t take long to explore our town,

only occasionally surprising,

pretty enough,

bedtime feels a little too early,

at the moment everyone has enough to eat.

Thank you.

So it was in the two worlds on either side of the neatest unfinished fence in history.