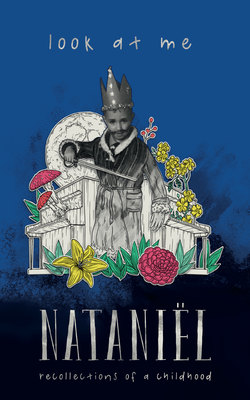

Читать книгу Look At Me - Nataniël - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Day One

Оглавление: Can he hear us?

: No, he’s in his room. Where’s your little one?

: At the neighbours’, they have an inflatable pool, I can’t keep him away from there.

: What are we going to do? It’s only a couple of weeks still!

: What can you do? You can’t run away, you can’t make time stop, we’ve gone ahead and bought the clothes.

: So have we, not everything yet, we have to go again. It’s not going to lessen the shock, but at least you can keep an eye on him when he tries things on, or sees the tiny school case, maybe there’s something that tells you if he’s going to be one of The Lucky Ones.

: I know! But we couldn’t figure out much. He was crazy about the tie that clips on, he even put it on again in the car. And the shoes! He keeps saying he’s big now. Like his cousins.

: We’ve considered just blatantly lying about his age and keeping him back a year, at least it gives you time.

: Yes, luckily they’re not some of those tall children.

: They are so little!

: Maybe the laws will change. You always hear about things happening. Some of them stay home now.

: Those are the rich people, they can do anything.

: What about The Prince? When The Prince comes, everything is different!

: When has The Prince ever come here? We only hear about others who are saved in faraway places, never a place we know.

: They say he makes some disappear, others go to places that have been set up just for them, some live and learn under domes, with their families, imagine that! Only The Merciful can see them!

: We can only hope! And ask around! It’s safe to ask, right?

: We’ll manage something. I won’t let my child perish.

: My child is special, none of this lot is going to know what he needs.

: Where are you, Prince?

This conversation never took place. They were in the lounge, my mother, my father, Derick’s mother and father. I was in the passage and could hear everything, they talked about the price of school clothes, who would drop off and pick up the children until they were old enough to walk by themselves, it really wasn’t far. And it would be completely safe if they walked together. And keep out of the road if a car came. Except if it rained, of course. And then there were things like sport and choir practice, but that would surely only start in a year or two. So they talked, but The Conversation never took place. How could it? They didn’t know about it. Neither did I. I only wrote it down recently, The Conversation All Parents Should Have Before Children Are Sent To School, Especially If Children With Fairy Dust Are The Topic Of Discussion.

And The Prince? No one knew about him then.

And so, a few weeks later, without intervention, without trumpets and heralds announcing the new rules, absolutely ordinary, as if it were completely natural, the school year begins. Day One starts like we’re on a ship, my mother looks like she always does, my father too, the house hasn’t lost its shape, but everything else is strange, I am unsteady on my feet, the world wobbles. I am wearing my new clothes, white shirt, thin grey jersey, grey shorts, grey socks, black shoes. (Now I realise they might have been other colours, but all the photos from those years were black and white, thus I am all in grey.)

In my hand is a school case, a hard, small brown suitcase. Inside is a lunchbox with sandwiches, also a square plastic bottle with red cooldrink, a handkerchief, an apple, two big books, one with light-blue lines, one without, and a small bag with coloured pencils. I like my school case a lot, it smells brand new. I open the lid and turn back to my closet.

No, no, says my mother, You don’t have to take any toys, they have everything. Come along, we don’t want to be late.

It is a terrible thing when something familiar suddenly comes to life and shows you that you knew nothing, you are caught unawares. We have gone past the school a hundred times, it is between the church and the dormitory, on the way to three regular places we went visiting, but today it swallows us up, in at the tiny gate, up the stairs, past a hall, round a corner, past a pillar, another pillar, children, children, children, into a classroom. Here is your chair, here is your desk, here are your parents, they are now strangers, they are going to leave you right here, look at them laugh, talk to other strangers, they wave to you, you don’t wave back, you look down. What is rubbing like that? It is the block around your neck, a dark-grey, flattish, rough block, it presses against your stomach, scratches your throat, it’s your fear, from now on it will always be with you, no, you’re not sleepy, no, you’re not weak, no, your legs are strong enough, it is only the block that’s still new, yes, the nausea is completely natural, you will get used to it, you are drifting now, like you’re on a ship, the ship is swaying on the sea, on the ship is a swimming pool, it is also swaying and you are in that water. You are swaying along with the sway of the sway. You are not dying, you are just not touching the ground. You hear everything your teacher says and you do what you must, she is one of The Merciful, she sees you, she sees you are drifting, but she cannot stop it, she must do her job.

I liked Miss Van Wyk a lot, she was friendly, not friendly enough to say school is over now, but she did have compassion. (Those were Grandmother’s words, if someone showed you compassion, you were safe.) In a photo in my album I am sitting next to her, you can’t see at all that I’m drifting, I am smiling broadly. On my chest is a paper face with my name.

What I like a lot, despite the ship and its swaying and the block around my neck and my parents who are missing, is the smell in the classroom. Powder paint, starch paint, watercolours, plasticine, crayons, glue, wooden blocks, wooden beads, paper of every thickness and texture, together all of this creates a smell that I will recognise for the rest of my life in studios and workshops, the places where craftsmen slave away to give shape to something unrecognisable or unreachable.

From somewhere comes a voice I don’t know, a man’s voice, he is talking to me, softly and calmly: It’s not so bad, see? It’s not that bad at all.

Outside someone rings a bell. Miss Van Wyk makes us stand in a row.

Are we going home now? I ask. But the block presses against my throat and makes my voice hoarse, nobody hears me.

It’s break time, says Miss. We are all going to walk together to the trees, there you can play and eat your sandwiches. If someone wants to go to the bathroom, just tell me and I will walk with you.

So I learn a term that holds more fear and cruelty than any ghost story Grandfather could ever think up. Break time. My block is heavy, I struggle to breathe, I just follow the child in front of me. I don’t look up, I only see shoes, there must be more than a million, all the shoes look like mine, I look up slightly, everyone’s clothes also look like mine, why? So we can disappear like those pieces of my puzzle with the big sky? My mother and father will never come to look for me, they are at home with my baby brother. Why do they want me gone? And these children! Why are they yelling so? And jumping like goats? Don’t they know we’ve been thrown to the wolves? (Also Grandmother’s words.)

Here I learn another thing, suspense. I drift, now among the million identical children, nobody hurts me, nobody says anything funny, nobody grabs my sandwich, but I’m waiting for it, there is no one who can help me here, Miss can’t watch everybody, why is there a break? Why must you leave your desk and your case? Surely you can play at home!

I look up. No, look down! There are bigger children at the building with the toilets. They are watching us. I chew my sandwich. I like eating, but here I taste nothing.

The day lasts another thousand hours. I don’t know how I got home. I have a star on my forehead and a drawing in my hand.

Oh, that’s pretty, says my mother. What is it?

It’s a ship, I say.

I only see blue, says my mother.

It sank, I say.

My mother puts down the drawing.

How was Day One? she asks.

What is Day One? I ask.

Your first day at school! Tomorrow is Day Two!

Do I have to go again?

My mother laughs.

Oh, she says, You’re such a comic!