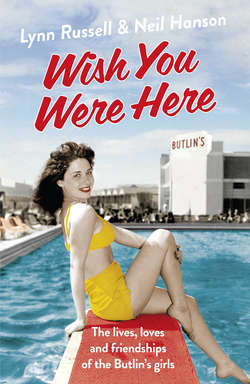

Читать книгу Wish You Were Here!: The Lives, Loves and Friendships of the Butlin's Girls - Neil Hanson - Страница 11

One

ОглавлениеMavis Idle began working at Butlin’s as a musician and redcoat in 1959. She was born Mavis Wilcock in Dewsbury, Yorkshire, in the summer of 1938 in her grandmother’s terraced house. Unable to afford to rent let alone buy a house when they got married, Mavis’s mum and dad were still living with her grandmother at the time. Even when they eventually got a house of their own, it wasn’t that far away – just two doors along the street. It was an old type of terraced house, with no bathroom and a toilet outside in the yard. Like most people they knew, they would get the tin bath out on a Friday night and the whole family would take it in turns. Although it lacked modern amenities, it was a decent house, stone-built, very solid and in a good street, and Mavis had a very happy childhood there.

Her father had a job winding coils for an electrical transformer company, while her mother looked after Mavis and her little brother, Roy. They were a musical family. Her father used to play the harmonica pretty well, Roy played the guitar for many years, though he eventually gave it up, and Mavis played the accordion.

One of her relatives on her grandma’s side used to make concertinas and accordions for a living, and Mavis often wonders if her interest in them stemmed from that, but as far back as she can remember, she always wanted to play the accordion. Her dad often used to take her to shows at the Dewsbury Empire Theatre when she was little, and she was so small that she would have to sit on the steps down the aisle, because she couldn’t see the stage otherwise. She can still remember the tingle of excitement she felt as the house lights began to dim and the orchestra struck up. The shows staged there were always variety bills in those days, and they almost always started with a musician. Whenever it was an accordion player, Mavis used to say to her dad: ‘When I get big, I want to have one of those.’

She kept on and on at her parents about it and in the end, when she was still only about six or seven years old, they bought her an accordion. It was only a tiny one, but still it felt so heavy to little Mavis that she could hardly pick it up. She enjoyed playing it from the start, though. ‘My granddad always wanted to listen to me playing it,’ she says, ‘or at least he said he did! And he helped me a lot with it. When you start on the accordion, you just learn the keyboard to begin with, using your right hand, and then you learn to do the bass – the buttons – with your left hand afterwards. Granddad used to say to me: “It’s all right you learning the keyboard, and then learning the left hand, but when you come to put it all together and you’ve got to pull the bellows as well, what are you going to do then?” And we’d burst out laughing together. I can still remember how thrilled he was when I did it for the first time.’

Mavis was a pretty good dancer as well when she was small. She danced from when she was a tot until she was about nine, and with the rest of her dancing school she appeared in her first pantomime at the Empire Theatre when she was five. ‘So that was the beginning of my show-business career!’ Mavis says with a laugh. It was a big theatre, seating 2,000 people, and although the pantos they put on there were all home-grown, they were some of the best in the whole of the North, with future stars like Hylda Baker and Morecambe and Wise among the guest artistes and most performances sold out weeks in advance. People came from all over Yorkshire to watch them.

Mavis appeared in the pantomimes until she was nine, but then had to choose between dancing and the accordion, because to do both was just too much of a commitment. She loved dancing, but she loved her music even more, so she gave up her dance classes and concentrated on playing the accordion.

This was probably just as well, because soon afterwards, in January 1947, she was involved in a serious road accident and damaged her foot badly. She had been to a dressmaker who had made a coat for her. On her way home, Mavis got off the bus and crossed the road. She already had one foot on the far pavement when a coal wagon passed so close behind her that its rusty mudguard caught in her coat. She let out a shriek, less in fright than in horror at the damage to her new coat, but the impact then span her around and threw her into the side of the lorry, while one of its wheels ran over her foot, crushing it.

Mavis doesn’t remember anything for two weeks after that. She was in hospital for quite a while, and if she had still been having thoughts of being a dancer at that stage, it would have been a very difficult time for her, because the specialist who was treating her said, ‘I’m afraid you won’t ever be able to wear high heels, and you won’t ever be able to dance, and you won’t ever be able to play sports.’ However, this just made her all the more determined to prove him wrong. And although there has been a weakness in that foot ever since, while she was still at school, she played all the sports, like hockey, tennis and rounders, and when she grew up, she not only wore high heels, but danced in them as well.

When her baby brother Roy was due to be born – he was nine years younger than Mavis – her parents sent her to stay with an aunt in Kent for a couple of weeks to keep her out of the way. When Mavis got home, she discovered that she not only had a new baby brother, but a new accordion as well, because her father had bought her a proper, grown-up one. It had belonged to her music teacher’s son, a brilliant accordionist who had tragically died very young. Her teacher often used to say to her, ‘You play like my Jack used to play,’ and he really wanted her to have the accordion, but money was so tight that for quite a while her parents couldn’t afford even the modest price he was asking. However, in the end her dad found the money and bought it for her. She was so thrilled when she saw it, she could hardly speak.

Mavis passed the eleven-plus and went to grammar school, and had a vague idea in her mind that she’d like to do something connected with art when she grew up. It turned out that her career would not be in art, but in music, and she started working as a professional musician when she was still very young. She had carried on with her accordion lessons and practised really hard, and by the time she was twelve years old, she was good enough to be playing on stage.

A friend of hers who ‘did a bit of singing’ told her that a comedian called Ken Idle was holding auditions for a concert party he was putting together, and she asked Mavis if she’d go with her. Ken had been in the forces doing his National Service, but was now looking to make a career in entertainment, and as a first step was planning to put on shows for charity. So Mavis and her friend went along to the auditions together, which were being held at the house where the concert party did its rehearsals.

Mavis was petite and nimble, with a dancer’s natural grace, but she was also painfully shy at the audition, so much so that she could hardly speak, and she was very much in awe of Ken, who was twelve years older than her – twice her age at the time. The other musicians weren’t as old as him, but even the youngest of them was four years older than her. Although she was so young, Mavis was fine once it was time to play her accordion for them – it never bothered her to play her accordion in front of strangers or on stage, because she knew she could do it – but ‘I couldn’t have spoken on stage to save my life!’ she says. ‘Even when I was a lot older, I could never even introduce a song; I just didn’t talk on stage at all.’

She passed the audition and started playing with the concert party, and continued doing that for the next couple of years. The troupe had separate boy and girl singing groups, but Mavis rarely sang; she mainly just played her accordion. Eventually, the four boys decided to break away, as they’d had enough of just playing for charity and wanted to start playing the working men’s clubs and making some money from their music. They asked her if she’d play accordion with them. She was only fourteen and still at school, but she jumped at the chance.

So instead of playing the odd concert party, usually in the daytime at weekends, Mavis was now out several nights a week playing the clubs. It certainly wasn’t the way to great riches; ‘I remember the first club we ever played,’ she says. ‘They gave us three pounds ten shillings for our night’s work, and that had to be shared between five people! However, we were convinced we were on the path to fame and fortune and we gradually got more and more bookings. Sometimes we even got slightly more money as well!’

Every time they had a booking, Mavis would hurry home from school and grab a sandwich, the boys would then pick her up in the van and they would be off to whatever club they were playing at that night. She’d be sitting in the club’s dressing room doing her homework before they went on stage. Her exams were looming and she was beginning to panic about them, so she’d do some of her homework, then do the spot on stage, then come rushing off stage, do some more homework in the interval and then go back on stage. By the time they’d packed up their kit and driven home again, it could easily be midnight, or even later. It was a crazy schedule, but they kept working the clubs for quite a few years.

Looking back now, Mavis is amazed that her parents didn’t try to put a stop to it. ‘To be honest,’ she says, ‘I think they were quite intrigued by it all. They couldn’t believe what was happening; it was a whirlwind for all of us! When we were playing somewhere local, they used to come and watch us, and we eventually got to the point where we had coach-loads of people – friends, and even a few fans, I suppose – coming to see us wherever we were playing.’

Mavis left school when she was sixteen. She had it in mind that she was going to be a fabric designer, but when she told the school careers officer this, he put her right off the idea, telling her there was a new machine that had just been brought out that could print hundreds of different designs.

‘He was talking nonsense, of course,’ Mavis says. ‘It wasn’t like today when they have computers that can do all sorts of fabulous things, but I didn’t know that at the time.’ So she ended up in a rather less stimulating work environment: the accounts office of the British Rail goods department. It was a job, at least, but she was still playing in the clubs at night and often not getting to bed until the early hours, so she admits that she probably wasn’t the most wide-awake or efficient accounts clerk British Rail ever had.

Over the next couple of years, the group went through three different line-ups and eventually dwindled to just three people: Dave, Ken and Mavis. So they formed a trio and carried on doing the clubs for a while, calling themselves The Verdi Three. Mavis chose the name, just because the accordion she used was a Verdi III and she liked the name.

When Mavis had joined the group at just twelve years old, the gap between her and Ken had seemed like a chasm. He was everything she wasn’t at that time: mature, poised and confident. He was a grown man who’d been away in the Army, and had been working as a professional musician and comedian, and she was just a kid, a schoolgirl, who happened to be able to play the accordion. She was more than a little in awe of him. ‘Though I might have had a bit of a teenage crush on him as well,’ she says, ‘he was really more like a much older brother to me.’ By the time she was seventeen, however, that began to change, and despite the age gap there was definitely some chemistry between them. They started spending time together off stage as well as on, and although they never really went courting (as they called it in those days), because they were always on stage in the evenings, and very rarely went out on a proper date, just the same, they were going out together from 1955 onwards.

When Mavis told her parents, they were nervous about it at first, especially her mother. Mavis remembers her asking, ‘What happens if he meets someone his own age and doesn’t want you any more?’ Both her parents came round to the idea fairly quickly, though. They knew Ken pretty well by then, because five years before, when Mavis had started playing with the band, her dad had made Ken promise that he would always make sure she got home safely. So he’d always see her to the door and say hello to her parents and sometimes, if it wasn’t too late, he’d pop in for a cup of tea before he went home.

Rumours had started going round her school that Mavis was going out with a bandleader from the moment she had started playing with the group. ‘It made me laugh at the time,’ she says, ‘because it sounded like I was going out with Joe Loss or Mantovani!’ So when she actually did start going out with Ken several years later, her friends were already quite used to the idea, and most of them didn’t really react to the news. There were inevitably some people who showed their surprise. A couple of her friends said, ‘Why are you going out with an older man?’ One even asked her if she was going out with Ken just because he was so popular. (Working as a comedian, Ken often had the audience in hysterics when he was on stage, and he was fairly well known locally as a result.) Most people, however, just accepted their relationship.

In the summer of 1956, Mavis and Ken went on holiday to Butlin’s Skegness with another couple. Mavis had been away without her parents before; when she was fourteen she went to Morecambe with a friend, which they both thought was very grown-up, even though they stayed in a boarding house run by her friend’s aunt, so they weren’t completely unchaperoned. Before she went to Skegness with Ken, however, she’d never been to Butlin’s and didn’t really know a lot about it, other than the things she’d read in magazines.

The camp seemed enormous. Mavis can remember walking along the road that ran between the rows of chalets on one side, and the shops, bars and theatres on the other, and she could just see the big old-fashioned merry-go-round at the entrance to the fun fair right at the far end – ‘It looked miles away!’ she says. The camp was like a mini-town and she felt sure she’d always be getting lost, but once she got used to it, it no longer seemed as vast as it had on that first morning.

The camp also seemed to have a glamorous air, even if it was sometimes only skin-deep, with its ‘marble’ columns that were actually painted plywood. Another girl who made her first visit to Butlin’s at the same time remembers being overwhelmed by the facilities, which were quite unlike anything she had ever seen before. She still recalls how ‘gorgeous and opulent’ the ballrooms were, with their chandeliers and the smell of polish from the gleaming dance floor.

The redcoats also made quite an impression on Mavis. Speaking of when she later became a redcoat herself, she says, ‘If we were not quite idolised, we were certainly very popular and admired by the campers, and I think I felt the same about them when I first went there as a holiday-maker. They always looked amazing and were always smiling and chatty, and very friendly.’ She doesn’t know if she really got the most out of Butlin’s at the time, because she was too shy to enter most of the competitions, though she did a few of the sports and games. Ken certainly wasn’t shy about getting up on stage, but then he’d been doing it for years. Mavis wasn’t the same kind of performer.

They could only afford to stay for a week, but Mavis and Ken had a great time while they were at Butlin’s and loved all the entertainment, including the Champagne Spinner in the ballroom on a Friday night. This was a big dial at the side of the stage, which had numbers painted round the edge and an arrow in the middle. The redcoats would spin the arrow and if it was pointing to the number of your table when it stopped, you got a bottle of champagne – at least, they called it champagne; it was fizzy and went ‘pop’ when it was opened, and best of all it was free!

Mavis even quite liked the stream of Radio Butlin’s announcements over the tannoy, apart from the early-morning ones, which would ease you out of a deep sleep with what was supposed to be soothing music.