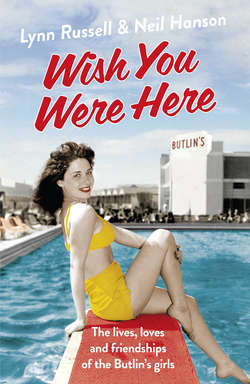

Читать книгу Wish You Were Here!: The Lives, Loves and Friendships of the Butlin's Girls - Neil Hanson - Страница 7

One

ОглавлениеHilary Cahill was in her late teens when she first heard of Butlin’s in 1957. Born in 1940, she grew up in Bradford in a solid working-class home. Her mum worked in Whitehead’s mill in the city and her dad was a foreman at Croft’s engineering works, so although they were never wealthy and lived in a back-to-back terraced house, with two good wages coming in there was always food on the table.

Her mum was a dark-haired, attractive and lively character. She absolutely loved to dance. It’s where Hilary got her own love of dancing from, because her mum taught her when she was small. However, her dad couldn’t dance to save his life. ‘He used to claim that it was because he’d never had any shoes when he was young,’ she says, ‘and only had boots, but that sounded like a bit of a lame excuse to me. He was still using the same excuse when I was a teenager! My mother and I tried to teach him over and over again, but whatever we tried, it just didn’t work. He had two left feet and that was the end of it! All the mills used to have these big dances once a year and we used to go to all of them, dressed in our best clothes. The real top bands used to play at them, so they were great. My dad used to hate it, though, when we all went to the works’ dances and my mum would be dancing away with people while he was just sitting there, looking on.’

Her dad was so strict that Hilary was still forced to wear little white ankle socks even when she’d left school, but she had a strong independent streak, so she used to go out on Tuesday nights wearing the ankle socks, telling her dad that she was going to the Guild of St Agnes at church, like a good Catholic girl, but then sneak off to the dance hall instead. She’d take off her ankle socks and put them in her bag, put on a bit of lipstick and then dance away with her friends until it was time to go home. However, her dad obviously suspected that she wasn’t quite as good a Catholic girl as she was pretending, because one night he followed her. As she was walking along she felt a hand on her shoulder, and there was her dad looking absolutely furious. ‘I want you back in the house, now,’ he said. ‘Get those socks back on your feet and wipe that dirt off your mouth.’ She was more embarrassed than frightened, but she knew that there was no use in arguing and that it was the end of her Tuesday-night excursions to the dance hall.

Her brother was five years older than her and almost as strict as her dad. He used to go to the same dance hall as Hilary and her friends and, she says, ‘He always kept his beady eye on me!’ She didn’t mind that – she quite liked the idea of her big brother being around. They were good pals, despite the age difference between them – and five years was a lot at that age. He didn’t snitch on her to her dad, but he would certainly let her know if he thought she wasn’t behaving like his little sister was supposed to. After her brother left school, he worked as a wool sorter and then did his National Service. She didn’t see him for almost two years because he was serving out in Cyprus during the troubles there, and she missed him a great deal.

Hilary went to a Catholic school in Bradford, but, looking back, she couldn’t say it was a very good education, and like the majority of her school year, she left at fifteen with no qualifications. Her first job was at J. L. Tankard’s carpet and rug factory in Bradford. She was employed in the finishing department, doing hand-sewing. It was all piecework and hard graft, but as young girls do, she and her workmates had a few laughs along the way.

One of her friends, Brenda, was a dab hand at doing hair and used to style theirs for them in the toilets at work. The girls would give her some of their ‘tickets’ – the slips of paper detailing the piecework jobs they’d done – so that she didn’t lose out financially from the time she was taking off work to cut their hair. ‘The Grecian styles were in then,’ Hilary says, ‘so we were all there at work with steel wavers and pin curls in our hair, singing along to the songs on the radio.’ After work they all used to go dancing together. Once she was paying her own way in the household, Hilary’s dad had to ease the restrictions on her, and from then on she and her mates were out every night of the week, either in the Sutton Dance Hall, the Somerset, the Queen’s or the Gaiety. ‘We used to go all over to dance,’ Hilary says.

Hilary and her workmates used to pay into a kitty to save for all sorts of things, including what they called the ‘Christmas Fuddle’. It took only a penny or twopence a week each, but when Christmas came around, that was enough to buy plenty of drinks, crisps and sausage rolls, and on the last day before the Christmas holidays they would stop work at lunchtime and wolf down the lot! Very few of them drank as a rule, but they certainly made up for that at the Christmas Fuddle. Deaf to parental warnings to ‘never mix your drinks’, they drank bottle after bottle of Babycham, Cherry B, Pony and Snowball – so much so that Hilary was pretty ill one year, and when she got home her parents weren’t impressed by the state she was in. The next morning, suffering her first hangover, Hilary wasn’t very impressed either.

As well as the kitty for the Fuddle, Hilary and the other girls were also saving for a holiday together, having made up their minds to go to Butlin’s at Skegness the following summer. They saved up all year, putting away whatever they could afford. Hilary used to put five shillings a week (25p) into a little tin towards her holiday, and saved half a crown (12½p) for clothes and shoes. She had to give her mum money for her board as well, and whatever was left after that she’d usually spend on going dancing.

There were fixed holiday times in all the industrial towns and cities then, when factories and mills would shut down for their annual clean-up and overhaul; an avalanche of, say, West Midlands car workers would descend on the holiday resorts one week, followed by Lancashire mill workers the next and Yorkshire miners the week after. In Lancashire mill towns the annual holidays were called ‘Wakes Weeks’, in other areas they were called ‘Feasts’ and in Bradford the holiday was known as ‘Bowling Tide’ – which was nothing to do with bowls, since Bowling was one of the Bradford districts and ‘tide’ was the local word for a holiday, as in Whitsuntide.

One woman from Bradford remembers her holidays as always being a bit of a home from home, because everyone from her street went on holiday to the same place at the same time. ‘You knew everyone when you got there, because it was all people from your street. I mean, you weren’t with any strangers, because even if you didn’t know them as such, you knew their faces.’ Since all the mills and factories in an area would shut down for the same week, tens of thousands of people were going on holiday at once, and they had to book far in advance – months or even a year ahead – because popular destinations like Butlin’s became full up very quickly.

In the 1940s and 1950s, when Butlin’s was at its peak, there were virtually no package holidays, and only the well-off could afford to travel abroad, so the holiday camps had a vast semi-captive market. The chalets may have been basic, but at a time when many young couples spent their first years of married life under the roof of one of their parents, a chalet at Butlin’s was often their first real taste of domestic privacy.

Very few families owned a car and the fact that everything you could want was in one place at Butlin’s was another powerful attraction. Once they got there, wives were freed from the toil and drudgery of factory work or housework – or both – for a whole week; few families could afford to stay for a fortnight. An article in Holiday Camp Review in 1939, ‘Holiday Camps and Why We Go There’, even claimed the camps were pioneering women’s rights. ‘At a camp alone a woman gains that pleasing sense of equality. The girl of eight, the maiden of eighteen, the grandma of eighty, rank with the boy, youth and grandpa without any sort of distinction. They are campers, first, last and all the time. Age and sex do not matter.’ It’s hard to think of any other British institution at the time where similar claims could be made with a straight face.

Unless they were in a self-catering chalet to save money (and they weren’t introduced until the 1960s anyway), there was no cooking, washing or cleaning for the women to do, and even childcare could be handed over to the nursery nurses or the redcoats in their signature red jackets, white shirts and bow ties, white trousers and white shoes. The children were marched off to sports tournaments, swimming galas and the Beaver Club (for small children) or the 913 Club (for nine- to thirteen-year-olds), or, if the weather was wet, to the endless array of rides, games, sports and competitions held in the ballroom and children’s theatre. So while their kids ran wild in safety, parents could swim or play sports if they felt energetic, or put their feet up and relax if they didn’t. They could sunbathe if the weather was fine, doze in an armchair if it wasn’t. They could play bingo or even booze the day away in the bar if they felt like it.

Even those with smaller children were liberated from their responsibilities to a certain extent. While parents ate at the oilcloth-covered tables in the dining hall, the under-twos were fed their puréed beef and carrots and stewed apple in a separate ‘feeding room’ in the nursery, where rows of babies in highchairs ate their baby food away from the other campers – or at least that was the theory. The babies were supposed to stay there until their parents and older siblings had finished their own meals in the dining hall, but the babies often had other ideas and would howl the place down until their parents collected them. Some put their little children in their prams outside the dining-hall windows, lining them up so that the babies could see their parents through the window. One camper recalled that, even from the other side of the glass, the babies’ screams could be heard above the clatter of cutlery and the noise of conversation.

Parents were also free to dance in the ballroom, watch a show in the theatre or drink in the bar in the evenings, while ‘chalet patrols’ – nursery staff in their blue uniforms and capes – marched or cycled up and down the lines of chalets, listening for crying babies. Freed from the burdens of childcare and factory or domestic drudgery for a week or two, many couples also rediscovered the pleasure they had taken in each other’s company in the early years of their relationships – although for others, the unusual amount of time spent with their partner could also have the opposite effect!

In 1957 Hilary and her friends went to Butlin’s at Skegness for the first time. Four of them went, sharing one chalet. Hilary’s brother had a car, a Morris 1000, and he offered to take them there, so they all squashed in with their suitcases piled on the roof rack and set off. They had driven only a few miles down the road when the car broke down. When they should have been driving in through the gates of the camp at Skegness, they were still sitting in the broken-down car, waiting for a tow truck.

It was pouring with rain all day and by the time they got to the camp they were tired, bedraggled and fed up. Like all the girls, Hilary’s friend Brenda was on her first trip away from home, and her mother had bought her a brand-new suitcase to take on holiday. It was so wet that the handle disintegrated and fell off as she was carrying it through the camp. Despite the trials and tribulations of getting there, however, as soon as they saw Butlin’s, they absolutely fell in love with the place.

All along the road leading to the camp there were tall flagpoles with different-coloured flags flying, and there was always a row at the front of every Butlin’s camp, too. ‘You could see them flying from about a quarter of a mile away,’ one camper recalled, ‘and as you drove up to the main entrance, the first excitement was seeing all those flags blowing in the wind. When I saw that, I knew that I wouldn’t be seeing much of my parents for a whole, wonderful week.’

As they turned in through the gates, the girls could see the tropical blue colour of the big outdoor swimming pool, and the theatres, dining halls and other main buildings, all freshly painted in brilliant white with the details picked out in bright primary colours. Rocky Mason, a former redcoat and entertainments manager who spent most of his working life at Butlin’s, can still recall similarly vivid memories of his very first sight of Butlin’s as a boy. He’d grown up in ‘a very dreary city, covered in mill smoke. It was very dull and the sky was always grey. When I got to the camp I felt as if I’d suddenly walked into utopia – it was so colourful, so warm, so friendly. There were lights across the roads, there were banners fluttering in the breeze, there seemed to be music coming from every direction. The swimming pool was the most beautiful, beautiful thing I had ever seen, there were flags all around the pool and it was a stunning colour of blue. I saw rows and rows of chalets, all with different-coloured doors and windows – red, yellows, blues, greens, orange – it was just a gorgeous place to be and there seemed to be laughter coming from every building.’

Hilary couldn’t have imagined a greater contrast with Bradford, which was a very wealthy city then but also a very drab and grey one. There was a near-permanent pall of smoke hanging over the city, fed by hundreds of mill chimneys, and the golden-coloured sandstone of the buildings was stained ink-black by decades of coal smoke and the sulphurous winter smogs.

The rest of Britain was just as dreary during the 1940s and 1950s. The last phase of wartime rationing only ended in the mid 1950s, and even though ‘utility’ clothing was no longer the only option, clothes were still invariably made of wool or cotton, in black or muted shades of green, brown or grey. Television – for those families that owned a TV set; it was still a luxury item – was broadcast in black and white. The first colour television broadcast in Britain did not occur until 1967. Radio was still dominated by ‘received pronunciation’ and the Reithian requirement to inform and educate, rather than entertain. And even in the late 1950s or early 1960s, most of the music played on the BBC Light Programme would have been equally familiar to listeners in the 1930s. Given this backdrop, the Butlin’s camps, with their rows of colourful flags, bright-blue swimming pools and dazzling white buildings with vividly painted doors and windows, must have looked positively psychedelic to 1950s eyes.

Butlin’s was impressive enough by day, but by night it was staggering. You could see the glow from all the lights from miles away – and there were thousands of them. It had the same level of impact then that Las Vegas has today, and Hilary and her friends had simply never seen anything like it. She couldn’t get over how huge the camp was, either (when full, it held something like 12,000 people then), and the lines of chalets seemed to go on forever.

The individual chalets themselves weren’t quite so impressive. They were tiny, and had a little sink in the corner with a small mirror over it, a curtain across a tiny alcove to serve as a wardrobe, a small table, one chair and four iron, army-surplus bunk beds. That was it. Hilary remembers noticing that the bedspreads matched the curtains – blue with white yachts on them – and that the same motif edged the tiny mirror above the sink. Butlin’s kept these the same for years. Although there wasn’t much spare room, it suited the girls fine. They were only sixteen or seventeen, and until then they’d always been on holiday with their parents, staying in boarding houses or campsites. Hilary doesn’t think any of them had ever even stayed in a hotel, so to be off on their own, with their own separate chalet, tiny though it was, seemed quite sophisticated.

The redcoats made quite an impression on Hilary, too. The girls all looked very smart and glamorous to her, but they were friendly, too, and seemed to be absolutely everywhere, organising everything, making sure everyone was having a good time. Hilary and her friends had a ball while they were there, dancing every night, chatting and flirting with boys, and generally doing all the things their parents wouldn’t have approved of. Some of the girls even destroyed their holiday snaps before they went home – not because they were doing anything particularly wrong, but the photographic evidence of them just talking to boys or having a drink or cigarette in their hand would have been enough to get some of them, including Hilary, into serious trouble.

It continued to pour with rain for almost the entire week. The only fine day was the Friday just before they went home, so they spent the entire day, Hilary says, ‘running in and out of the chalet, changing our clothes and then taking another set of photos so that when we went home, we could show our friends the photos and make it look like we’d been having wonderful weather and a really great time every day of the week!’

Despite the weather, they had all loved their first holiday at Butlin’s – so much so that before they left to go home they all said: ‘We’re definitely coming back, and what’s more, we’re going to have two weeks next year.’ So as soon as they got home, they booked the next year’s holiday and began saving for it straight away. By the time the second year came round they all had steady boyfriends, and Hilary was actually about to get engaged to hers – a boy called Dave – but nothing, not even that, was going to get in the way of her holiday, so she took a deep breath and said to him: ‘All of the girls are going on holiday together. We booked it a year ago and even though I’m going to be getting engaged to you, I’m still going on holiday with them, without you.’

She’s still not sure what she would have done next if he’d said that he didn’t want her to go, but he just shrugged and said, ‘Okay,’ so that was that.

That second year, 1958, there were twice as many of them: eight girls, four to a chalet. The camp was packed with crowds of people all having a good time, and as they strolled around, the group of girls met up with gangs of boys and chatted and flirted with them, and then went dancing in the ballroom every night. Even though none of the girls really drank, they would still call in at Ye Olde Pigge and Whistle early in the evening. The bar was huge and had a fake tree in the middle of the room and a half-timbered, mock-Tudor ‘street’ down one side, with the ‘windows’ opening onto the bar. It was just as bizarre as it sounds! They’d stop in there for a little while, chat to the boys and have a soft drink, and then they’d go to the ballroom. They would still be there, dancing away, when the boys all came through after the bars had shut, and then they’d be dancing with them and generally having a good time until the ballroom closed down for the night.

One night they were chatting to a group of boys, and one of them was a real joker. He wasn’t tall or short, broad or skinny, or particularly handsome, but he stood out from the crowd and Hilary can still clearly remember him. This lad was asking Hilary what she thought she was going to do with her life when one of her friends butted in and said: ‘Don’t bother asking her. It’s too late for her, she’s already spoken for. She’s getting engaged when we go home.’

He just looked Hilary straight in the eye and said, ‘It’s never too late, until you’re standing at the altar in front of that man with his collar on back to front, saying “I will”.’

She just laughed at the time and thought no more about it, but when she got home, what he’d said kept coming back into her mind. She did get engaged to Dave and, as girls did in those days, she began saving and putting things away for her ‘bottom drawer’. She might buy a pillow case one week, a towel the next and a saucepan the following week, and put them all away in the bottom drawer of her dressing table, ready for when they set up home together. ‘It was how people did it in those days,’ Hilary says. ‘You had to save for everything and buy it a bit at a time, whereas now people just go and buy what they need on credit, all in one go.’

At that point in her life, Hilary could easily have gone ahead and got married, and would probably have had a child before she was twenty, but she went to the cinema with Dave one night and there was a travel documentary showing, the short film they always put on before the main feature. ‘Usually I was bored to death with them,’ she says, ‘but this time, as I was watching this film showing all these exotic places in different parts of the world, I thought to myself: you’re only eighteen, and there’s a whole world out there you haven’t seen and know nothing about. There and then I decided that I was too young to get married and wanted to see a bit more of life before I was ready to settle down, so I broke off the engagement with Dave straight away. He was a lovely lad and he took it very well. I mean, he was upset at first – we both were – but I was sure I’d made the right decision and I didn’t go back on it.’

Hilary went back to going dancing every night with her friends and was really enjoying herself. None of them were engaged or married, or even going particularly steady with anyone, so, still inspired by that short film she’d seen, Hilary said to them: ‘Why don’t we all go off somewhere together, like Australia, or Canada, or anywhere, really? There’s got to be more to life than we’ve seen so far. Let’s go and find out what we’ve been missing!’

It wasn’t that she was unhappy at home; she had a very happy home life. Her parents had just moved from the back-to-back terraced house she’d grown up in to a new house on an estate called Holmewood. ‘It’s not got a good reputation these days,’ she says, ‘but when they moved in there, just after it was built, it was wonderful. It had a bathroom and all the mod cons that we’d not had before.’ So her life was comfortable, she was happy enough and not short of anything, but she just felt that she wanted to do something else and see more of the world than Bradford.

So in early 1960 Hilary and her three closest friends made up their minds that, yes, they’d go off somewhere together and have an adventure! Based on little more than the fact that it had looked beautiful and very different from Bradford on the travel documentary Hilary had seen, they decided they would all go to Canada, so they applied for visas, got all the forms and filled them in. However, a couple of the girls then started to get cold feet, and the other one started going out with a boy and didn’t want to leave him, so in the end Hilary was the only one ready to go. She didn’t feel let down or fall out with the girls about it – ‘They were very good friends to me then, and I’m still friends with them over fifty years later. I go on a night out with them all every now and again, and two of them still live in the same village as me now’ – and it didn’t shake her own determination to do something different before she settled down.