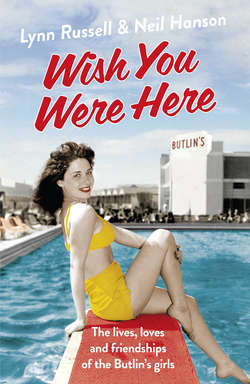

Читать книгу Wish You Were Here!: The Lives, Loves and Friendships of the Butlin's Girls - Neil Hanson - Страница 8

Two

ОглавлениеHilary freely admits that she wasn’t brave enough to go off to Canada on her own. She was so disappointed to miss out on the trip that she said to her friends, ‘Well, I’m going to do something. I’m not just going to stay around Bradford for the rest of my life.’ A couple of days later, she saw a Butlin’s advert in the local paper and decided that she wanted to work for them. She thought to herself: there are things going on all the time there, and I’ll not just be working, I’ll be enjoying life as well. She certainly did that, but having only seen Butlin’s from the other side of the fence as a holiday-maker, she didn’t realise quite how hard she’d have to work.

She applied to be a redcoat, and although she wasn’t an entertainer – she couldn’t sing, play an instrument or do stand-up – she could certainly dance; she had learned tap and ballet when she was younger, after all. She went for an interview at a hotel in Leeds and was a bundle of nerves going in there, but the man who was interviewing her was very friendly and put her at ease. She told him she could dance and liked meeting new people, and after they’d chatted for a while he offered her a job as a redcoat at Skegness.

Hilary didn’t start right at the beginning of the season – not everybody did. The camps opened to the public at the beginning of May but weren’t as busy then as they were in high summer. So instead, Hilary started working in mid May and then went right through until the end of the season in September. When she arrived, she found that some of the redcoats had been there for a few weeks already (they would prepare for the new season and hold themed activity weeks at the camps from mid April), and quite a lot of them had worked for Butlin’s before, at Skegness or one of the other camps, so they helped her and the other newcomers to settle in. She was excited and also very nervous, but she found that she felt at home right away and loved every minute of it. ‘I don’t know if I was a typical redcoat,’ she says. ‘In fact, I don’t know whether there is a typical redcoat at all, but I certainly wasn’t a real extrovert, and I never had a great deal of confidence, though it developed over the years.’

The redcoats’ jackets were laundered for them, but they had to wash the rest of their clothes themselves. Luckily, the white pleated skirts and blouses that Hilary and the other girls wore were drip-dry, so they just had to wash them and hang them up. They were allowed two each, but they’d always try to get an extra one, as it did make life a little easier: one on, one spare and one in the wash. Redcoats always had to be smart – Hilary wore white stilettos all day, apart from when she was on the sports field – and they all had to have a little white handkerchief showing in their top pocket and to wear their Butlin’s badges. They issued a different badge for every camp, every year, and people used to collect them. ‘You’d sometimes see campers coming in’, Hilary says, ‘with what looked like about a hundred badges pinned to their hats or coats.’

During the week, Radio Butlin’s at Skegness used to wake the campers with ‘Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah’, and there would be similarly jolly music all day, every day, except for Saturday – leaving day – when they were woken to the wistful strains of Mantovani’s ‘Forgotten Dreams’. The solemn music would continue all morning as the campers wandered around looking sad at the thought of going home. Some tried to cheer themselves up by booking for the following year before they left.

The redcoats would see the same families coming to the camp year after year. Some of the wealthier families ‘hardly ever seemed to be away from the camp at all’, Hilary says. It’s a testament to the strength of the connection many of the campers felt that one woman, who had been to Butlin’s over fifty times, even asked for her ashes to be sprinkled onto a flowerbed at her favourite Butlin’s camp after she died, because, according to her daughter, ‘This is where she called home.’

Hilary had to learn the rules that the redcoats had to follow, and there were pages and pages of them. ‘You couldn’t go dancing with just the pretty girls or the handsome men, or dance with anyone more than twice, and you had to seek out the reluctant dancers, the shy people and the wallflowers, and get them on the floor as well. You weren’t allowed to have anything in your pockets, because it spoiled the lines of your uniform, and I used to smoke then, so it was a struggle to know where to put your cigarettes. One of the boys, a black guy who had an Afro, used to keep his cigarettes and his lighter hidden in his hair!’

Hilary fell foul of one of the numerous Butlin’s rules when the local paper sent a photographer along to take a picture of the tug-of-war contest they were holding on the sports field. When the paper came out, right on the front page there was a picture of Hilary standing up and cheering on one of the teams. She was delighted to see herself in the paper, but then her heart sank. She knew she’d be in trouble when she saw that the photograph clearly showed her holding a cigarette, with a rolled-up Butlin’s duty roster sticking out of her jacket pocket. Staff members weren’t allowed to smoke when they were standing up – Hilary could never understand why, but you had to sit down if you wanted a cigarette. Sure enough, when the entertainments manager saw the picture, he called her into his office and gave her a dressing down.

At Skegness the redcoats put on various sporting events and had to go around the camp often literally dragging people out of the dining room or wherever they were to take part. The campers were divided into ‘houses’, like in public schools – in Skegness’s case, named after the royal households of Kent, Gloucester, Windsor and York – and the redcoats had to persuade them into volunteering for all these competitions. They may have been on holiday, but the redcoats would make them practise every day and then take part in the events themselves. There was one gang of guys at Skegness who were there for two weeks. Hilary got hold of them in the first week and, after a bit of coaxing, got them doing the five-a-side football and a few other events. They actually won the football competition and were presented with their prizes: Wilkinson Sword razors, since the company was sponsoring the event. At the start of the second week she tried to get them to play football again, but they all said, ‘No, we’re on holiday. We were practising and playing all last week, and all we got at the end of it was a lousy razor each.’

‘You won’t get them again this week, I promise,’ she said. ‘I’ll make sure they give you a really good prize this time.’

In the end they agreed to do it, but they warned her: ‘If we get those razors again, you’re going in the pool, fully clothed.’

So they played and won the five-a-side competition yet again. Everyone was lined up on the sports field at the end of the week when all the prizes were being given out. When their names were called, sure enough the prizes turned out to be more ‘lousy razors’. They didn’t even take them, they just turned round, stared at Hilary and then came running towards her. They picked her up, carted her off and threw her in the pool fully clothed, and of course the other campers absolutely loved that!

As well as running the competitions, the girl redcoats had to make sashes and rosettes for them as well, which involved going down to the camp stores to get the material and then cutting them out and stitching them together. ‘You had to do all sorts for your team,’ Hilary says, ‘but if they won the overall competition at the end of the week, you got a small bonus. The redcoats were always very popular with the campers, and you would often get them saying, “Come and have a drink with us,” but we hardly had any time to spare. You might have got an odd ten minutes to go and have a quick drink with someone, but that was about it.

‘It was hard work, of course,’ Hilary says, ‘but there was always a real buzz and a feeling of excitement in the air. If something good wasn’t happening right now, then you knew that it would be before long. I loved meeting all the different people who passed through the camp, I loved the shows and entertainment and above all, of course, I loved the dancing!’

The working day normally finished at quarter past eleven with the redcoats singing ‘Good Night Campers’, but after that they still had to fit in rehearsals for the Redcoat Show – a weekly cabaret in which almost all of the redcoats performed sketches or songs. Other entertainment put on for the campers included such timeless favourites as knobbly knee competitions and beauty and talent contests galore. In later years, the Holiday Princess of Great Britain, the Glamorous Grandmother of Great Britain and the Miss She fashion competition were even televised. People came to Butlin’s to be entertained and to have a good time, and the redcoats had to make sure that happened. As another former redcoat recalled: ‘We would organise competitions, whist drives, snooker, football, darts, Glamorous Granny, Holiday Princess, as well as all the children’s competitions. We would act as bouncers in the Rock ’n’ Roll Ballroom, we would dance with campers in the Old Tyme and Modern ballrooms, some would act as lifeguards for both pools (indoor and outdoor), we would sit up till gone midnight doing the late-night bingo and then still be up for first-sitting breakfast at 7.30 a.m., smiling away as if our lives depended on it … and our jobs certainly did!’

Every night the redcoats were allocated their duties for the next day. If Hilary was down to do darts or some other competition that she found boring, a lot of the other girls would swap with her. They hated having to do the ballroom duties, like the Old Tyme, afternoon tea and morning coffee dances, whereas Hilary absolutely loved those, so the system worked perfectly. ‘I’d be there with my long white gloves on,’ she says, ‘and as long as my partners could dance, I didn’t care what they were like, I just loved it!’

In the ballroom in the evenings the redcoats would get everyone doing the Chopsticks. They called it that because the music they used was ‘Chopsticks’, but it also described what they did. Four redcoats would kneel down, each holding two long bamboo canes, and they’d begin banging them up and down and moving them in and out in time to the music. The campers – either volunteers or those conscripted by the redcoats – lined up in a long column and took it in turns to hop or dance in between the canes without getting their legs trapped. ‘When Jimmy Tarbuck was working as a redcoat,’ Hilary remembers, ‘he used to lift the canes so high you practically needed a step ladder to get over them! And of course when the campers tried to do it, they’d be falling all over the place. So it was a bit of a giggle for everyone.’

They’d do a limbo competition, too, not that it was any more serious. The redcoats would raise the bar to make it easier for the old and the overweight, but, Hilary says, ‘We’d have it practically touching the floorboards for anyone we thought was taking it too seriously!’

Hilary and the others also had to go ‘swanning around’ the dining room while the campers were eating their lunch or tea, trying to sell them raffle tickets to win a car. The redcoats were all given targets and had to sell a certain number of tickets each month, and if anyone did really well, they might get a little bonus as a reward; ‘It was really high-pressure stuff.’ The draw was to be made at the end of the season and the first prize really was supposed to be a car, though Hilary doesn’t remember anyone ever winning one. ‘Things are different now,’ she says, ‘but back then there was a bit of an “anything goes” mentality.’

Butlin’s had been a success from the start, but the camps really boomed in the post-war period, driven on by Billy Butlin’s risk-taking, entrepreneurial spirit and his flair for generating publicity, even if it involved telling a few white lies along the way. Long-serving redcoat and entertainments manager Rocky Mason recalls the time when Billy phoned a journalist on The People and told him that he was buying the Queen Mary to turn it into the largest luxury floating holiday camp in the world.

The story made headlines throughout the world. A few weeks later, the journalist phoned Billy to ask if there had been any developments. ‘None at all,’ Billy replied. ‘But how else could I get £100,000-worth of publicity for the price of a phone call?’

However, Billy wasn’t the only one with an eye for a publicity opportunity. In 1949, while he was surreptitiously trying to check out the competition at the Brean Sands camp of his rival Fred Pontin, Billy was unwittingly photographed having a drink at the bar. To his incandescent rage, the picture was then used in a Pontin’s brochure with the slogan: ‘All the best people come to Pontin’s!’

Billy Butlin had always thought big and was ever willing to gamble money on the newest and most eye-catching attractions. He opened his own airports next to some of the camps, allowing some holiday-makers to arrive by air, but also offering them pleasure and sightseeing trips. There were chairlifts and miniature railways at all his camps, and he also installed the UK’s first commercial monorail at Skegness. Some of the camps had vintage cars and famous old steam railway engines, which kids loved to clamber all over. But one of the greatest attractions at Skegness, both for the campers and for Hilary, was an elephant. Billy had been using animals as attractions since the early 1930s, when his Recreation Shelter in Bognor featured a zoo with bears, hyenas, leopards, pelicans, kangaroos and monkeys, and a snake pit where Togo the Snake King would stage regular shows. And both Filey and Skegness also had ex-circus elephants.

Hilary had always loved elephants. She had ridden one at Belle Vue Zoo in Manchester when she was a child and had never forgotten it. ‘It was a really big thing for me to see an elephant there at Skegness. And you can just imagine the faces of the children – and the adults – who were staying at the camp when they realised they could actually see a live elephant strolling through the camp with his keeper.’

Sadly, though, the elephant, called Gertie, came to an unfortunate end during Hilary’s first season. The trainer would lead Gertie up and down the camp every day and Gertie would do tricks, like picking up the trainer’s eight-year-old son with his trunk and putting him on her back. The kids used to love it, and there would always be a little procession of them following Gertie around.

She also used to go in the shallow end of the swimming pool and blow jets of water out of her trunk, washing herself and drenching anyone within range. She’d been doing this for years without coming to any harm, but one particular day, for no obvious reason, Gertie started walking down the pool, away from the shallow end and towards the deep end. Her trainer kept on shouting at her to stop, but Gertie just kept on going, and when she got out of her depth, she drowned. Even though Gertie hadn’t been at Skegness for long, for the staff, it was like losing a family member. It had happened in full view of the holiday-makers as well, so they were just as upset about it as the redcoats. Some of the kids were inconsolable. They had to drain the water and bring in a crane before they could get the elephant’s lifeless body out of the pool, so it was very traumatic for everyone.

Soon after she had started working at the camp, Hilary had got chatting to one of the other redcoats, a Londoner called Bill, who did general duties and also ran the sports events and competitions, including the boxing and wrestling matches, as he was a boxer himself. He wasn’t a typical redcoat at all, because he was public-school educated, and with her working-class background in Bradford, Hilary had never met anyone like him before. Redcoats weren’t allowed to socialise with each other during working hours – it was one of Butlin’s strictest rules – but Hilary and Bill would meet up after work and on their days off and they soon started going out together.

Like some of the other staff, Hilary stayed on for an extra two or three weeks at the end of the season to help out with the Christian Crusades Week (when hordes of religious people descended on the camp to hold their revival meetings) or other special events that some of the camps put on. There was also a Ballroom Week at many of the camps, when competitive ballroom dancers arrived from all over the country. After the last waltz of the evening, as the dancers left the floor and went back to their chalets, one woman still vividly remembers the excitement she felt as a young girl crawling round the ballroom floor on her hands and knees, collecting all the sequins that had fallen from the women’s ball gowns.

Once the camp had closed down at the end of September, Bill, who had found a job at Selfridge’s, was heading back to London for the winter, so Hilary decided to go with him. She started working as a waitress at the Imperial Hotel in Russell Square, but hated every minute of it. The head housekeeper, who was in charge of the staff, was ‘a real hard case’, she says with a shudder, ‘and so were most of the other women who worked there, so it wasn’t a pleasant place to work at all’.

After a few weeks of that, Hilary said to Bill: ‘I can’t stand it there and I’m feeling homesick, too, so I’m going back home to Yorkshire.’

‘All right,’ he said. ‘I’ll come back with you, then.’

Bill managed to get a job in Leeds doing credit-enquiry reports, and since Hilary’s parents had already met him and knew they were serious about each other, they let him live with them at their house. ‘Although, of course,’ she says, ‘we were in separate bedrooms and strictly chaperoned, so that nothing untoward went on!’

A lot of couples at this time had to live with one or other set of parents both before and after they got married, because very few could afford to set up home on their own straight away. After they’d been living with her parents for a few weeks, Bill said to her: ‘If we’re going to be living under the same roof anyway, there’s no point in us not being married, is there? So why don’t we just get married?’

It wasn’t the most romantically phrased proposal, but it seemed heartfelt, and even though they’d only been going out a few months and really didn’t know each other very well at all, Hilary said yes. She was still only twenty and had not seen much of the world except for Bradford and Skegness, but nonetheless, thrilled and excited, she threw herself into plans to get married a month later, on Christmas Eve.

Bill then set off back to London for a couple of days to break the news to his father; his parents were separated and he didn’t get on that well with his mother, so he was in no hurry to tell her. He was supposed to be coming back to Yorkshire on a train the following Sunday evening, but he never showed up. They didn’t have a telephone – a lot of people didn’t then – so there was no way that Hilary could get in touch with him or find out what had happened to him, but in any case, she wasn’t too worried at first. As the days went by and there was still no sign of him, however, she began to get increasingly anxious. She didn’t have a clue what had happened to him and before long she was going frantic with worry.

At last, on the Thursday of the following week, she got a letter from him, though it wasn’t good news. It read: ‘I’m so sorry, I’m so despicable and you must hate me, but I’m not sure if I want to get married.’ It went on in a similar vein for another two pages. It turned out that instead of going to see his father, Bill had gone to Butlin’s for the weekend instead: even though the season had ended, they still put on a few special weekend events at the Bognor Regis camp.

Hilary thought about it for a few minutes and then, ever resourceful and remarkably brave, she showed her mum the letter and said, ‘I’m going to go and see his father.’ She’d only ever met him once, and she didn’t even know his address. All she knew was that it was somewhere in Tottenham. I’ll find it somehow, she thought. So she cancelled everything: the cake, the ceremony and the reception, told all her friends and family that the wedding was off, and then set off to London.

She got off the train at King’s Cross, found her way to Tottenham and then wandered around the streets until, by a miracle, she managed to find the right house. She walked up to the door and when she knocked on it, who should answer the door but Bill?

When she saw him, Hilary did a double take and was lost for words for a few moments, but then she said, ‘I haven’t come to see you, I’ve come to see your father,’ and angrily pushed past him into the hall. When she had calmed down a little, they began to talk things over. Bill had changed his mind again and had now decided that he did want to get married after all, but his father sat them both down and offered them some advice.

‘You’ve rather rushed into everything, haven’t you?’ he said. ‘Why don’t you give yourselves a bit more time to really get to know each other and just get engaged instead?’

His words made sense, so that’s what they decided to do, but as Bill sat opposite her on the train back to Bradford, he said, ‘I’m so sorry about the way I’ve acted and what I’ve put you through, but I do know what I want now. So, if you’re willing, I’ll have a word with your dad when we get to Bradford and see if we can put it all back on again and still get married on Christmas Eve, just like we planned.’

If Hilary had any misgivings, she swallowed them and said yes to Bill for the second time. Her father obviously wasn’t pleased about the way his daughter had been treated, and when Bill asked him, at first he just shook his head and said, ‘Oh no, if you really want to get married, you’re just going to have to wait now, at least until Hilary is twenty-one.’

However, he gave in after a couple of days, so they rang the register office and spoke to the cake maker just in the nick of time – with Hilary having cancelled her order, he was just about to cut up the cake he’d made and sell it off! So, as they had originally planned, they got married on Christmas Eve, then caught the next train to London and had a two-day honeymoon at a hotel in Russell Square. They worked in London until the spring and then together went back to Butlin’s in Skegness for the start of the new season.

As married redcoats, instead of a chalet with bunk beds, Hilary and Bill were given one with a double bed in it, and Hilary did her best to make the chalet – their first home together – as cosy as she could. She put up their own curtains instead of the Butlin’s ones, and bought a little paraffin stove (even though it was strictly against regulations due to the fire risk) and used it to boil a kettle for cups of tea.

Halfway through the season, Bill was offered a promotion to deputy entertainments manager, but based at Clacton rather than Skegness. So they moved to Clacton and this time, when they got to the end of the season, Butlin’s offered to keep them on for the winter and sent them to work at one of the hotels they owned, the Ocean Hotel in Saltdean, near Brighton.

It was while she was working there that Hilary met Jimmy Tarbuck, who was also a redcoat at the hotel, and another Butlin’s girl, Valerie, who was to become one of her very best friends. Valerie was a redcoat, too, but was working as an entertainer because she had a great singing voice. She arrived at the hotel two days after Bill and Hilary, and the two girls hit it off straight away. Even though Hilary was newly married to Bill, she and Valerie were always together. Whenever they had time off or a break, they would get together for a drink, a few laughs and a dance. They learned all the new dances that were coming in, like the twist, the Watusi, the mashed potato and the locomotion – at the time it seemed like someone was coming up with a new dance every couple of weeks.

Coronation Street had just started on ITV and they both loved it, so they were always trying to sneak off duty and go to the television room to watch it. The ballroom at the hotel doubled as the venue for the cabaret shows, and Valerie and Hilary were often on duty together operating the spotlights and changing the colours of the acetate filters to suit whatever dresses the singers were wearing. However, the start of the shows coincided with Coronation Street, so, desperate to watch it, the girls decided that they would get two of the guests’ kids to do the lights while they sneaked off for half an hour. Children under the age of twelve weren’t allowed at the hotel, so Valerie said to Hilary: ‘All we’ve got to do is find the two tallest boys’ – they had to be tall to be able to change the filters and operate the lights – ‘and give them the sequence of acetates for the first half-hour, because Coronation Street only lasts half an hour, so we’ll be back before they get any further into the show. Simple!’

They found two tall boys who both jumped at the chance – they’d do anything for the redcoats, and playing with the spotlights sounded like good fun. So after giving them their final instructions, Hilary and Valerie left them saucer-eyed with excitement and went off to the television lounge.

Coronation Street was already hugely popular, its gritty realism, ordinary-looking characters and northern dialect a stark contrast to the ‘drawing-room and French-windows’ settings and received pronunciation of most other television programmes at the time, so a lot of the hotel guests were already in there with the lights off watching the show when Hilary and Valerie sneaked in. They sat down out of sight on the floor at the front and whispered to the guests: ‘Don’t let anyone know that we’re in here, will you? Or we’ll get into trouble!’

‘It was funny,’ Hilary remembers, ‘because a lot of the guests came from the South of England and they just didn’t believe what they were seeing on the screen when Coronation Street was on. They kept saying to us, “It’s ridiculous, people just don’t change the wheels of their bikes in their front rooms,” but we said, “Oh yes, they do in the North. Believe me, we’ve seen it!”’

Their plan worked; the girls’ young deputies did the job perfectly and no one noticed. When the boys went home with their parents at the end of their holiday, Hilary and Valerie found another pair to take over. To start with, all went well again, but one night, they’d only been in the TV lounge for about five minutes when they heard the entertainments manager shouting, ‘Where are they? Where the hell are they?’ And they didn’t need to be told who ‘they’ were. They tried to sneak out but walked straight into him and had to stand there, rather shamefaced, while he tore them off a strip. When he paused for breath, Hilary said, ‘How did you know we weren’t doing the lights?’

He burst out laughing. ‘Because it was like World War Two was starting all over again inside the ballroom. There were searchlights flashing all over the sky!’ The two boys had got bored with just focusing on the performers and had started swinging the lights all over the ceiling, pretending to shoot down enemy aircraft. The audience were in hysterics, but the artists who were performing on stage were rather slower to see the funny side.

As well as working in the Brighton hotel, the girls also went to the various campers’ reunions and promotional visits that Butlin’s held in cinemas, theatres and ballrooms all over the country during the winter. It was just one of the ways they tried to build loyalty in their campers and encourage them to book again the following year. People who’d made friends at one of the Butlin’s camps would arrange to meet up at the reunion, and redcoats would put on entertainment for them. On the Friday night it was like a show night at one of the camps, complete with all the entertainment, just to remind those who had been to Butlin’s what it was like, and show those who hadn’t what they were missing. Then on Saturday morning they would put on a big free film show at the local cinema. ‘There would always be kids queuing up to come in for the show,’ Hilary says. ‘And some of them broke our hearts because they were so poor. You’d see them standing out there in the freezing cold with no coats, no socks, and their little shoes with the soles worn through.’

Hilary and Valerie were always well aware that there were many people who were much worse off than they were, which helped to put any of their own troubles into perspective. A lot of disabled people, especially children, used to come to the camps with their parents or carers. ‘Even though they were only there for a week,’ Hilary says, ‘you often did get very attached to them, and it was the sort of job where you had to go and find them and make sure that they were having the very best time they could.’

While working at the hotel, Hilary also became friends with a few other redcoats, and has remained so to this day. Her friends Des and Mair met each other there and, like Hilary and Bill, later got married, and there was Rocky Mason, who also came from Bradford. ‘Perhaps because there were only a few redcoats working in the hotel,’ she says, ‘we formed a really close-knit group, almost a family. We got to know each other so well and I really became close to them all.’

In the spring of 1962, Bill was promoted again and sent to work at Minehead as assistant manager. Hilary went with him and became assistant chief hostess, but she still kept in close touch with Valerie and her other friends from the hotel in Saltdean. The camp at Minehead was brand new. When they were building it, there had been a lot of objections from the locals, because some of them didn’t want a holiday camp built there at all, but Billy Butlin always seemed to get his way in the end. He even managed to turn the one occasion when councillors defied him to his advantage. Having built the Heads of Ayr hotel in Scotland, Billy applied to the council for a late licence for the bars. His application was refused and when Billy told the councillors that he would rather demolish the hotel than run it without the late licence, they treated it as a bluff – whereupon Billy called in the bulldozers and flattened his newly built hotel. If that seemed to be cutting off his nose to spite his face, it proved to be good business in the long term, because no other councils were brave enough to call his bluff after that. The camps at Bognor and Minehead both went ahead despite vigorous local opposition, though at Minehead Billy used charm instead of bulldozers to win them over. He said to all the objectors: ‘When it’s ready, we’ll invite you all along and you can come and look around.’

So when the camp was ready to open, they laid on an inspection and an afternoon tea for the local people. Hilary was given the job of meeting some of them at the gate, showing them round the camp and then taking them for afternoon tea. There were a lot of ladies from the Minehead Women’s Institute there and they must have had a nice afternoon, because at the end of it they had a whip-round and tried to give her a tip. She had to tell them, ‘I’m sorry, ladies, but we’re not allowed to accept tips’ – it was yet another of Butlin’s rules. However, a couple of days later, a letter arrived for her, thanking her again and sending her a cheque for the amount they’d raised in their whip-round: £2. 10s (£2.50). Her wages were only about £4 per week then, so it was a very nice bonus, and Hilary was so touched by that gesture that she kept the letter and still has it today.

As a hostess, Hilary was in charge of the competitions and dealing with all the prizes – ‘and there were so many competitions’, she says with a sigh. A lot of them were sponsored by companies such as Lux Soap and Smiths Clocks, and the prizes for those were the sponsors’ responsibility. Butlin’s provided the rest of the prizes, and Hilary was given an allowance of nine old pence (about four pence today) per camper for the prize fund. In high season, when there might be 10,000 holiday-makers there, it added up to quite a lot of money, but earlier and later in the season it was a lot less. No actual money ever changed hands, because the camps had plenty of shops where she could obtain prizes, so she’d just go around them, choose what she wanted and the shops would then debit the value of what she’d taken against the prize fund.

There were prizes for all ages: toys for the small children, sports stuff for the older ones, scarves and handbags for the women and free holidays at the end of the season for the winners of the bigger competitions. The day after they’d given out the prizes was always bedlam in the camp offices, because people who’d won a prize would often bring it back and try to swap it for something else, either because they had already won the same thing earlier in the week, or simply because they didn’t like what they’d got.

The redcoats would always get a bit of stick from the parents of children who hadn’t won prizes, too, especially the parents of the kids in the Bonny Babies competition. ‘Everyone always thought their baby was the most beautiful baby in the world and wanted to win the prize to prove it,’ says Hilary, but dealing with complaints was all just part of the job. There was never any trouble with the competitions that were just a bit of fun, though, like the Knobbly Knees contest, or when they had campers doing stupid things on the sports field, like chariot races and pram races, with grandmothers in the prams instead of babies. There were one or two anxious moments, particularly when one granny was pitched out of a pram during a race and knocked out cold. Nowadays her relatives would probably have been phoning the lawyers before her head touched the ground, but when she opened her eyes a couple of minutes later, all she wanted to know was: ‘Did we win?’

The redcoats also had campers throwing eggs to each other and trying to catch them. At first, the eggs they were handing out weren’t real, and the campers would be throwing them to each other and stepping back a few paces every time, but of course eventually the redcoats would swap the pretend eggs for real ones, and when they tried to catch them, a succession of campers would be splattered with egg yolk.

They’d also get campers to take their shoes off for a barefoot race across the field. As soon as they said ‘Go’ and the campers had gone haring off over the grass, the redcoats gathered all their shoes together and then threw them up in the air so they came down again in a heap. When they got back, puffing and blowing from the race, the campers had to spend ages sorting out whose shoes were whose. ‘You couldn’t get away with that stuff now,’ Hilary says, ‘because people would either punch you or sue you for emotional trauma or something, but we got away with it back then!’

When the redcoats meet up at reunions now, they all talk about those days and say what happy times they were. ‘They certainly were,’ Hilary says, ‘but it was hard, hard work as well. You were so tired sometimes, but then you were working from eight in the morning until midnight, or even later, and the camps were so big.’ The redcoats often found they were at one end of the camp for one event and then had to go right to the far end of the sports field for the next, and they’d only have half an hour’s break in between them. Hilary had a bike for a couple of seasons, so getting around wasn’t so bad, but those who didn’t have a bike couldn’t even take five minutes off, as it would take half an hour to walk across the camp. So there wasn’t much free time, but there was, Hilary says, ‘still a lot of fun and a lot of camaraderie’.