Читать книгу The Long Journeys Home - Nick Bellantoni - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPrologue

Deborah Li‘ikapeka Lee, a young adult Native Hawaiian (Kanaka Maoli) woman, woke in the wee small hours of an October night in 1992 far from her homeland in Seattle, Washington, to an inner sensation, impossible to define and equally impossible to ignore. Alone and unsure of what was happening to her, she feared illness and anxiously rose from her bed searching for the comfort of her Bible. She felt as if she were being called to do something, but what? The sensation continued to well up inside her, forcing its way up and out, yielding a voice that spoke as clearly as if its source were standing in front of her. She heard five words: “He wants to come home.”

Marlis Afraid of Hawk, an Oglala Lakota grandmother (unci), heard her call in the form of a midnight reverie on a warm spring night in 2012. She dreamt of a young Lakota man with flowing hair on horseback riding toward her, clothed traditionally, blowing melodiously on a flute. She was a child in her dream, standing immobilized, transfixed as the anonymous rider motioned toward her to follow, turning his horse and riding away, leaving the earth behind, galloping into the sky. To her amazement, she recognized ancestors and tribal members, dressed in regalia, emerging from the surrounding clouds falling in line behind the mysterious rider, dragging their dog-pulled travois into the heavens. Who was this Lakota who could command followers? Why had he come to her? Marlis spent days searching for the meaning of her dream from the spirit world. Ultimately, consulting with tribal elders, cloaked in ceremony, the message was revealed: the young man was her father’s uncle, or in Lakota kinship, her grandfather (lala), who had left the reservation a long time ago, never to return. She was told: “He wants to come home.”

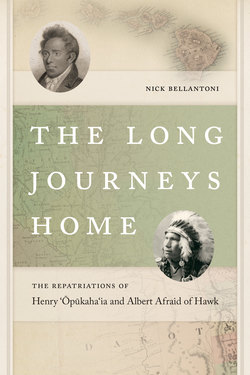

Two Native women heard spiritual appeals that eventually led them to Connecticut and my office. As the Connecticut State Archaeologist, a position I held for almost thirty years, I had the responsibility of supervising, in hopefully a professional and respectful manner, the archaeological removal and the forensic identification of the surviving skeletal remains of Henry ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia and Albert Afraid of Hawk, young men who died and were buried in our state in the 19th century. We worked with the Lee and Afraid of Hawk families and a team of funeral directors, forensic scientists, archaeologists, and historians to conduct the exhumations and prepare the remains for the final leg of their journeys home. Our involvement is the bridge between these Hawaiian and Lakota narratives.

Henry ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia considered leaving the Big Island in the first decade of the 19th century “rather than live without a mother and father”1 who had been brutally slain before his childhood eyes by Kamehameha’s warriors. As a teenager, he secured passage onboard an American merchant ship, sailing halfway around the world hoping to replace pain and memory, attempting to outrun his survivor’s guilt, seeking peace from the violence he experienced in his youth with its resultant despondency. His journey would take him to Connecticut, where he was introduced to Christianity, experienced a St. Paul-type revelation accepting Jesus as his personal savior leading to his study of the Bible in hopes of returning home as a missionary to convert Native Hawaiians to the Gospel, but tragically dying of typhus fever in Cornwall, Connecticut, on Feb. 17, 1818, and buried under frozen New England earth. Considered the first Christianized Native Hawaiian, Henry’s journey stalled far from his birthplace until Debbie Lee, Henry’s cousin seven generations removed, heard in the still of the night his desire to come home and began the process for his return.

Eighty years later, at the close of the 19th century, Albert Afraid of Hawk, Oglala Lakota Sioux, first-generation reservation Indian born in the earliest days of the Pine Ridge Agency in South Dakota, was also looking to leave his homeland. He set out with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West troupe to escape the stifling colonization of the reservation system that forced him to share his childhood with starvation and ethnocide, forbidding him the fulfillment of his Lakota birthright. His grandfather rode with the undefeated Red Cloud and instilled the childhood Albert with stories of past Lakota glories and their harmony and balance with the universe before the coming of the waschius (white man); his father was beside Crazy Horse at Little Bighorn fighting against George Custer’s Seventh Cavalry; and his older brother travelled with Spotted Elk (aka Big Foot), surviving the massacre at Wounded Knee. Torn between two cultural worlds, he yearned to find identity, which on the reservation was being denied by a dominant, subjugating society. He wanted to be Lakota, free as his grandfather and father before him had been—warriors, buffalo hunters, men of honor—not enslaved as wards of the federal government. He left the reservation hoping to assume that life, even as a show performer. His journey would take him throughout the eastern seaboard and eventually to Danbury, Connecticut, where he died June 29, 1900, of food poisoning and was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in Wooster Cemetery. His journey suspended far from his homeland until Marlis Afraid of Hawk, Albert’s grandniece, heard his yearning plea within a deep sleep and began the process of his return.

Teenagers when their journeys began, ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia and Afraid of Hawk had heard separate callings to leave their homelands, crossing over to inhabit the world of the cultural other. Traditional ways of life had already broken down due to contact with Western society, disrupting their Indigenous cultural systems and leading to intense warfare, depopulation, environmental destruction, and ultimately loss of lands to the American government whose imperialist goals purposely undervalued both Hawaiian and Lakota cultures by prohibiting practices, such as ceremonies, dances, traditional dress, and the speaking of their ancient languages. More than 100 years after their untimely deaths, descendant women would hear their spiritual voices and seek to repatriate their ancestors’ remains, completing their long journeys home.

While the odysseys of these young Native men and the aspects of Manifest Destiny that crippled their Indigenous life ways are analogous in a remarkable fashion, they also represent distinct cultural traditions (Hawaiian and Lakota), differing time frames (Henry died fifty years before Albert was born) and legacies (Henry became celebrated while Albert remained relatively anonymous). Henry was buried under a stone monument, especially built to commemorate his memory forever; Albert was interred in an unmarked grave, its location unknown for 108 years. These two accounts were chosen for this book not only due to my personal involvement, but to highlight the disruptive commonalities of expansionism that led to massive deaths, conflicts, colonization, and conformity that continue to shape contemporary Hawaiian and Lakota communities and the resurgence of both cultures.

We know more about the life of Henry ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia due to the posthumous publishing of his chronicles by Rev. Edwin W. Dwight than we know of Albert Afraid of Hawk, who has no written autobiography. The Memoirs of Henry Obookiah, A Native of Owhyhee, and a Member of the Foreign Mission School, who died at Cornwall, Connecticut, February 17, 1818, aged 26 Years, contains a first-person account of his life in Hawai‘i, his private New England diary, letters from the Congregational community, and Dwight’s heart-rending description of Henry’s death. Even 19th century authors like Mark Twain, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Jack London knew his story from Sunday school lessons. This book relies heavily on the Memoirs among other primary and secondary sources in relating ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia’s story and his impact on Hawaiian history.

Contrariwise, there are few primary documents referencing Albert Afraid of Hawk beyond U. S. Indian Census records, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West “Route Books,” and newspaper accounts of his death. The Lakota didn’t have a written language then, so only Euro-American records are available for us to reconstruct his life. After death, Albert, for the most part, had become anonymous, lost even to his family who never learned why he hadn’t returned home from his time with Buffalo Bill, and, except for photographs that Indian art collectors cherish in the Library of Congress, memory of him became obscured through time. As a result, we have taken more liberties with the telling of Albert’s story, reading between the lines and even going so far as to suggest motives for his leaving Pine Ridge. ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia had a profound effect on the Euro-American culture; Afraid of Hawk barely had the opportunity to penetrate it.

The physical remains of both men were archaeologically “resurrected” from their graves and welcomed home to great acclaim from long, arduous journeys. The parallels to their stories are striking. This book is an account of their lives, the histories of their people, and our experience repatriating their physical remains, an experience that has left me with a profound respect for the importance of family, heritage, and spirituality among Native communities in response to changes in the modern world and giving rise to my own personal journey as an archaeologist. In the spirit of Indigenous oral tradition, our approach in chronicling both long journeys home is through storytelling rather than scientific treatise. The danger of this approach is unintended romanticizing. The journeys they embarked upon were rites of passage, exhibiting universal elements of “separation, initiation, and return,”2 and, as a result, ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia and Afraid of Hawk have inadvertently become champions who reappeared to bestow promise, cultural continuity, and pride to their people. They are links to a cultural past that has been modified greatly by the modern world system. Their stories are inspiring and have contemporary connotations. Our challenge has been to introduce Henry and Albert to the reader in pragmatic, unsentimental ways without losing the moving experiences of their personal tragedies and the inspiration they provide to their descendants. My intent is to memorialize and celebrate Henry ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia and Albert Afraid of Hawk, not idealize them, though perhaps because of our personal involvement, I may fail at times.

When I began my study of, and subsequent career in, archaeology over forty years ago, contemporary Native Hawaiian/Native American communities and anthropological archaeologists rarely communicated. Archaeologists piously believed that they were the scientists, the PhDs, the experts in antiquity. What could contemporary Indigenous Peoples tell us about their unwritten past that has been so changed, so distant, and so unlike their lives today? They surely had lost too much to ever recall their unrecorded cultural history.

This view of Indigenous Peoples’ ability to tell their own stories contained unintended and, at times, intended Western racist undertones. Archaeologists felt no compelling need for consultation with tribes. We analyzed pottery shards and stone points, wrote manuscripts about the cultural behavior of “prehistoric peoples” and made careers without regard to, or input from, the descendants that manufactured the objects of our study. We simply did not appreciate how our research into the distant past affected the lives of living people. Accordingly Native Peoples viewed archaeologists as part of the exploitative system of Western society that killed millions of their ancestors, took their land, and left them impoverished on reservations of the U. S. government’s making. We took, rarely gave back, and never associated with them.

I distinctly remember attending a powwow in the mid-1980s and hearing Dakota actor and activist Floyd (Red Crow) Westerman express his indignation through an audio speaker heard throughout the entire fair grounds, that Indian people had two enemies in this world: the FBI and archaeologists! I was stunned when he said that.3 I didn’t get it. How could he compare archaeologists, me, to the sometimes strong-handed tactics of the Federal Bureau of Investigation on Indian reservations? After all, weren’t we working to preserve Native American heritage, to help them restore their cultural past?

“Archaeologists,” Red Crow explained, “dig up the bones of our ancestors, study them in laboratories, and exhibit them for people to gawk at. Archaeologists hold our ancestors prisoners in museums! And the FBI unjustifiably arrest and hold our young Indian men in federal prisons! Prisons for our ancestors! Prisons for our youth today! They are both our enemies!”4

Over the years I had nurtured developing friendships within the Connecticut Native American community, and nervously I scanned the fair grounds wondering whether they looked on me as an enemy. I was confused, angry, and ashamed—all at the same time. They were infuriated; we were arrogant. Neither side understood one another or seemed to care to.

As an undergraduate student in anthropology I had read treatises by the Lakota scholar Vine DeLoria, Jr., who harshly criticized anthropologists citing our motivations as benefiting ourselves and doing nothing to respect the concerns of Native Americans who were against our actions perpetrated in the name of “science.”5 With the rise of Red Power in the 1970s, Indian activists expressed their distress by disrupting archaeological excavations, conducting “sit-ins” at museums, and organizing “The Longest Walk” from San Francisco to Washington, D.C. to bring attention to Native American anxieties about the desecration archaeologists were wreaking at burial sites across the country and the museums that housed the bones of their ancestors on hidden storage shelves. I understood these concerns intellectually, but not emotionally; after all, I was training to be a scientist and convinced myself that our work, in the long run, would benefit the Native American community. Nonetheless, Indian activism was bringing about a change within our science and a lot of soul-searching.

In the early 1980s, I was a graduate student in anthropology at the University of Connecticut entrusted with the forensic analyses of seven Indian skeletons earmarked for the first-ever Native American reburials in the state by the Connecticut Indian Affairs Council. Invited afterwards to the re-interment ceremony, I met a young Native man who seemed to have nothing but contempt for me. We launched into a long discussion, really a debate/argument, on the treatment of human skeletal remains. By handling the remains I was playing with fire, he warned me, a nuclear energy that would subsume me because of my “disrespectful work.” I responded with hopes that my “forensic work” made the reburials more personal since I was able to give description to each individual—sex, age, diseases, life stress pathologies, and traumas—by letting their “bones” speak to their personal histories from hundreds of years ago. I hoped that our work made the ceremony more meaningful. The young Native man counter-argued that he didn’t need science for him to hear his ancestors’ stories; he heard their voices whenever he sang to them in the forest. It was all he needed to know. I countered that I heard them, too, but through the physical study of their “bones.” We parted not truly comprehending each other’s perspective: mine steeped in western material science, his embedded in Native spiritualism.

Five years later when I became the state archaeologist with the role and responsibility to work with Indigenous Nations over their concerns about archaeology, vandalism, and the adverse effect of construction activities on sacred sites, I began to meet regularly with tribal representatives, participating in powwows and other gatherings. Gradually, I was developing an understanding and sensitivity through dialogue and personal relationships. While I was going through this incipient transformation in the late 1980s, I met Maria Pearson (Hai-Meacha Eunka, Running Moccasins), a Yankton Sioux woman who became the “voice” for the pan-Native American reburial movement. Maria and a nationwide delegation of tribal leaders had been invited to the annual meeting of the National Association of State Archaeologists to address their concerns over the differential treatment of Indian burials by state governments.

Maria related an account that simply put the issue into perspective for me. Her husband, John, she told our gathering, worked for the Iowa Department of Transportation, and one day he came home telling a troublesome story. An unmarked pioneer cemetery had been encountered during road construction activities. All the remains were removed and reburied into another cemetery except those identified as a young Indian woman and her baby, whose skeletons were sent to the state archaeologist for study and repository. Maria was astonished. Why were the two Native burials treated differently than the white burials? Why were Indian remains considered objects of study while Euro-American remains were respectfully reburied? Under the United States’ own laws this differential treatment was plain and simple discrimination. Maria spoke eloquently and persuasively, presenting a straightforward, sincere story that put a complex controversy into perfect context.

Attitudes have changed remarkably since the 1980s. Archaeologists and Native Americans and Hawaiians have since opened up dialogue to mend misunderstandings and to develop trust relationships based on communication and personal empathy. While many Indigenous Peoples remain angry and many archaeologists continue to be suspicious, both communities are working to find common ground. Many tribes see the benefit of archaeological investigations and have gone so far as to engage archaeologists to jointly work with them on their reservations.6 Many archaeologists today are employed by Native communities and have developed equitable partnerships forging research designs benefiting both parties. Sonya Atalay’s book on “Community-based Archaeology” represents, in part, a methodological paradigm shift that incorporates descendant communities into the scientific process from conception to interpretation.7 Archaeologist Chip Colwell has examined the history of repatriation and offers model examples for what improved relationships between archaeologists/museums and Native communities should look like.8 In the last decade, collaboration has increased and the number of college-trained Native American archaeologists has skyrocketed.

Connecticut is a marvelous example. The Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation has developed a world-class museum to tell their story to the public, much of it stemming from their own sponsored archaeological investigations. The Eastern Pequot Tribe has coordinated with the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in conducting archaeological surveys on its North Stonington reservation for over fifteen years. The Mohegan Tribe of Connecticut has trained tribal archaeologists overseeing cultural resource management projects and below ground historical research in their homeland. Times have changed and for the better.

Repatriation of Indian skeletal remains and tribal artifacts of cultural patrimony is now the law of the land. At the federal level, the U. S. Congress, influenced in part by the activism of Maria Pearson and others, approved the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) in 1990 acknowledging that federal agencies and funded institutions, housing artifacts and human remains originating through the cultures of contemporary descendant Native peoples, have an obligation to collaborate with those communities and return human skeletons and items of cultural patrimony when requested.9 While NAGPRA remains controversial, complicated, confusing and is not always a given, the law does represent a philosophical and legal shift in the Native and scientific/museum communities.

At the state level, the Connecticut General Assembly passed legislation creating the Native American Heritage Advisory Council (NAHAC), providing tribes (federally and non-federally recognized) input to the state archaeologist and State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) on matters of Indian burials and sacred sites (C.G.S. 10-388, et.seq.). Though many states have preservation mechanisms incorporating Native voices, NAHAC is uniquely poised as a state agency with advisory responsibilities for responding to issues protecting burials and sacred sites on private lands. As a result of this consultation process, Connecticut has reburied scores of Native American skeletal remains and funerary objects, including those housed in museums and accidently discovered during construction activities.

Fearing the loss of valuable artifacts and human skeletal collections, many museums have resisted NAGPRA mandates by searching for technicalities in the law. Many cases brought by Native American tribes seemed to represent differing views of resistance or respect by museum authorities, whose stance seemed not to recognize that this land originally belonged to the tribes.10 As a result, cogent arguments have to be made by Indigenous Peoples seeking the repatriation of their ancestors or artifacts of their heritage with the legislative burden on them to demonstrate patrimony. Museums simply did not want to give up what they felt they were preserving for all of humanity and the advancement of science regardless of whether the people who had a cultural continuity to those artifacts and skeletons objected. How were museums to educate the public to the diversity and artistic achievements of Native American cultures if their collections were returned to the tribes, who would then have the ability to keep them from the public if they deemed appropriate? How were we to advance scientific knowledge of the history of diseases and the migration of ancient peoples if Native skeletons were reburied?11

By the time the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) was enacted by the federal government, our office had been working with the Connecticut’s Indigenous Peoples for a number of years and had prepared artifact inventories for the state’s two federal-recognized tribes: The Mohegan Tribe of Connecticut and the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation.

In 1996, we received requests for repatriation from both tribes. At the time, the Mohegan were actively working with ten museums to recover sacred items associated with their tribal history, including nineteen objects from the Norris L. Bull Collection, which were part of the Anthropological Collections at the University of Connecticut. Based on our inventories, all of the requested objects had been removed from 17th century Mohegan burials with the exception of one artifact, a two-faced soapstone effigy pipe that belonged to the Uncas family and had originally been taken from a significant cultural site referred to as “Uncas Cabin.”

Uncas was the first sachem (paramount chief) of the Mohegan Tribe and probably their most important cultural figure in the Post-Contact Period. Mohegan oral tradition indicates that pipes of this kind had been passed down long before Europeans arrived and are still in use within the Mohegan community. Mohegan traditional religious leaders indicated that present-day adherents for the practice of traditional Mohegan religion would use this particular steatite pipe.

Of the eighteen objects found with human remains, eight were recovered from the Royal Mohegan Burial Ground along today’s Elizabeth Street in Norwich, Connecticut. This well-known Mohegan cemetery had been badly disturbed through economic development and looting over the last 200 years. In the Bull Collection, grave goods from the Royal Mohegan Burial Ground consisted of a charm stone, a faceted orange glass bead, one trade axe, metal and stone pestles, a trade snuffbox, a copper kettle, a black angular stone pipe, and a paint pot with ocher staining, among other funerary objects.

Based on our inventory catalogue, there was no question that these cultural items belonged to the Mohegan Tribe and had been disrespectfully removed from graves and by unauthorized digging at Uncas’ Cabin. So, based on our own information, when tribal representatives requested repatriation from the Connecticut State Museum of Natural History at UConn, there was no question regarding the cultural affinity of the funerary objects. With both parties in agreement and after posting notice in the Federal Bulletin, the formal NAGPRA repatriation occurred in April 1996.

As far as early repatriations would go, this case represents one of the least contentious returns of Native artifacts at that time. Our records were undisputable as to the shared relationships between these items and the Mohegan Tribe, so there was no reason for us to question their cultural affiliation. But, I think there was another reason for the smooth transfer of these sensitive cultural items: a trustworthy relationship that had developed for over a decade. Along the way, I made mistakes and at times circumstances between our office and the Connecticut tribes became emotional and contentious. But I like to think that through it all, a confidence developed; one that came with time, respect, and personal empathy. We came to understand each other’s needs and we worked together for a common goal.

Unfortunately, in many NAGPRA cases, museum personnel and Native People may not know each other or have had the time to develop trusting relationships. In many cases, the road has been bumpy to say the least. Sometimes inventory records and cultural affiliations are not as clear; sometimes more than one tribe may make claim to cultural items. Regardless, there is no substitute for a personal rapport built on a history of communication and mutual respect. Only when we open dialogue with each other and appreciate and address concerns can we seek common ground and do what is right for everyone. Repatriation does not have to be contentious, but it does require dialogue, an understanding of motives, sensitivity, and the willingness to work together. I take heart that the repatriations of ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia and Afraid of Hawk are examples of that confidence and cooperation.

Through this compliant give-and-take, dialogues have opened up, forming pathways to learn from each other. I can testify that the science of archaeology has benefited from its association with Indigenous Peoples around the globe, and we hope that Native populations have also gained from the relationship. Most archaeologists have acquired a degree of sensitivity, and Native Americans have come to appreciate the contributions of archaeology to an understanding of their past.12 We are not enemies; we all make mistakes and are constantly learning. With any change of direction, it can be a long, slippery road to mutuality, but we are working together and making remarkable advancements. The pendulum has swung from exclusive control of Native American artifacts and human remains by museums and archaeologists toward Indian communities exerting their rights to have those objects and remains returned and reburied according to their own cultural prescriptions. We can envision a day when the pendulum will settle supported by shared respect and partnership.

The repatriations of Henry ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia and Albert Afraid of Hawk did not fall under NAGPRA review because they represented the private actions of individual families requesting the disinterment and re-interment of a genealogical ancestor. Had the reburials of Henry and Albert come under NAGPRA jurisdiction, consent would have been required from tribal governments, including lengthy reviews and a six-month wait after publication in the Federal Register of the intent to repatriate. The process would have been more formal and protracted. Be that as it may, all families have the right to disinter and reinter the remains of their ancestors. The deaths and burials of Henry and Albert, far from their homelands, were the result of historical happenstance. In returning them home, the completion of their journeys has had significant personal meanings for their families and Native communities, and, subsequently, special and surprisingly emotional connotations for the research teams that assisted in their repatriations. Although ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia and Afraid of Hawk will endure in Connecticut history, Hawai‘i and Pine Ridge will always be “home” and where their mortal remains should rightfully reside.

As I tell the story of these amazing young men and their families from a Western scientist’s perspective, it unavoidably relates my own personal development as an archaeologist. Like Henry and Albert, I unconsciously set out on a profound journey which began when I started listening to, and learning from, Native Peoples over four decades ago, hearing their voices and concerns.13 It took time, but through dialogue and development of personal relationships, I like to think that confidence was built. I was the outsider, the government official relegated with legal responsibilities and decision-making authority. Yet I assumed my duties seeking to understand a Native perspective toward my actions as a state archaeologist. Eventually, like Debbie and Marlis, I, too, would hear Henry and Albert, though not through dreams and inner feelings, but through a calling to use my training as an archaeologist in returning these young men home. From a Native perspective, I have been told, and I do believe, it was not an accident two such repatriations occurred during my tenure—they were meant to happen.

In many ways, though, this is not my story to tell, and I do not claim to speak for the families or for any Native Peoples. However, my involvement in these repatriations serves as the hinge between the two narratives, the bridge that connects Henry to Albert. My contention is that the science of archaeology does have a meaningful role assisting Indigenous communities in the return and respectful treatment of their ancestors. Our archaeological and forensic teams had to meet legal obligations defined by the State of Connecticut for the removal, identification, and return of Henry and Albert. These are secular requirements using Western state-of-the-art scientific techniques and methodologies, but we never lose sight of the fact that we are human beings handling the remains of other human beings. Hence, there are also solemn concerns demanding the ethical and sensitive approach in accordance, in these particular cases, with traditional Native Hawaiian and Lakota belief systems. Our role was to partner in the respectful excavation, sensitive analyses, and preparations for the subsequent reburial directly with the families of ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia and Afraid of Hawk, who have contributed in innumerable ways to this book.

The long journeys home of Henry ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia and Albert Afraid of Hawk are genuine American stories, embarrassingly recounting the disgraceful dealings of the government toward Native peoples in Hawai‘i and the High Plains of the North American continent. The United States, soon after its forming, was not content to simply trade with Indigenous Nations. With westward expansion the government wanted their land, seeking to conquer and undermine their cultures through dominance and colonial tactics. My involvement and telling of these stories are inescapably part of this long history of oppression and subjugation, but I hope that my respect for the men whose remains were returned to their families comes through on all of these pages. The author makes no claim of being Native Hawaiian or Lakota and does not speak or read their languages, so I take on the responsibility of telling these stories with a degree of apprehension and humility, knowing that I cannot convey the complexity of their cultures or the colonial quandary they have been exposed to from a firsthand, insider’s view, but only hoping that my outsider’s perspective does some justice to these historical accounts and their interpretations for the general public to appreciate.

Told through the personal account of the participating archaeologist, The Long Journeys Home transcends historical narrative in its relationship to contemporary Native Hawaiian and Native American families dealing with culture change in the modern world, seeking respect and honor through their collective pasts. It chronicles the Polynesian discovery of Hawai‘i, Kamehameha’s wars of unification, the establishment of the Protestant Christian missions in the Pacific, the political coup appropriating Hawai‘i from Native control, Hawaiian efforts to obtain sovereignty, Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery, Red Cloud’s War, the Battle of the Little Bighorn, the establishment of the Sioux reservations, the horrific carnage at Wounded Knee, and the resurgence of Lakota culture.

Furthermore, the book is about modern archaeological and forensic science and the partnership created with Native families in order to find common ground in the appropriate treatment of their ancestors by bringing them “home.” The assertion of this book is that archaeology and Native concerns are not mutually exclusive, not even in opposition, but strongly interrelated. Archaeologists are not “enemies” and neither are Indigenous Hawaiians and Americans. Working in partnership, scientists and Native Peoples can bring closure for families and honor to the ancestors by completing their journeys home. My goal in writing this narrative is not to enter into debates about repatriation, for others have represented both sides of the argument more effectively than I can; my hopes, though, are that the reader comes away with a better appreciation of repatriation, as well as a greater understanding of the process of “working together” through a personal account. The Lakota say, “Mitakuye Oyasin”—“We are all related.” In many respects, it has been a journey for all of us: archaeologists have listened to Native Peoples and in return they have listened to us. This book also aspires to introduce the reader to the lives of these two remarkable Indigenous men, their individual and family struggles, and the resurgences of Hawaiian and Lakota culture that Henry and Albert have in part contributed toward.

With these factors in mind, we embrace the spirit of Maria Pearson and Native oral tradition by employing a narrative approach, story-telling, weaving the past and the present throughout the book, a hybrid of history and memoir, not necessarily in a linear, chronological order but in an informal manner that emphasizes the circular notion of time without losing sight that these are as much contemporary stories as they are also American history.