Читать книгу The Long Journeys Home - Nick Bellantoni - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2 | “I Have Neither A Father Nor A Mother… But, He”

She awoke with a start, rising up in bed while the room was still draped in eerie nightly darkness. As she later explained to me, something strange was happening to her that she did not understand. A sudden rush emerged overwhelmingly from the depths of her inner being like a swelling impulse needing to be forced out. Her heart raced, short of breath. “What is this?” she thought, unsure if health was failing her young adult body. Rather than asleep, now, at two in the morning, she was wide-awake and anxious.

Debbie Li‘ikapeka Lee, thirty-two years old, a seventh generation cousin of Henry ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia, rose from her bed and took hold of the Bible on the nightstand, seeking comfort and reassurance. She recognized the need to let go of this feeling though she remained puzzled, “What am I to do?”

It was Sunday, Oct. 11, 1992, in Seattle, Washington, a thousand miles of ocean separating her from her devoted Hawaiian family in Hilo. Alone in the dark, she sought an explanation for this feeling that was mounting inside her. The Bible brought solace but no immediate clarification. Then from within her heart and soul, five words emerged in a voice as clear as if being spoken, “He wants to come home.”1

The surfing waves of Kealakekua Bay began to fade from sight. Onboard the Triumph, setting sail eastward toward the Baja coast, ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia and Thomas Hopu occupied themselves by learning the work of a luina kelemania e: preparing sails, climbing yardarms, pulling and tying ropes, and doing their best to stay out of the way of experienced sailors. They were unwittingly components of a diaspora that would diffuse hundreds of Hawaiian men to ports around the globe. ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia loved his uncle and grandmother and he would surely miss them, but the urgency he felt was overwhelming, driving him forward on his journey. Challenged by the uncertainty, he was in pursuit of a new life, an existence rid of the violence and despondency that took its unrelenting toll on his youth. The physical journey over the vast oceans would be outward, his personal quest rooted within the depths of his psyche inward.

The sailors began calling ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia, Henry, a name Capt. Caleb Brintnall entered into the ship’s log and, in an attempt to pronounce and spell his Hawaiian name, they contrived the phonetically sounding, “Obookiah.” Accordingly, “Henry Obookiah” would become his common name onboard ship and for the rest of his life in New England.

The crew of the Triumph reunited with more than twenty sailors decamped off the Baja coast to procure seal furs for the China trade. One of the crewmembers culled was Russell Hubbard, a Yale College divinity student who embarked on this sea voyage to improve his health. Hubbard took a shine to the bright and engaging Hawaiian and took it upon himself to tutor “Obookiah” in the fundamentals of the English language, using the Bible as a primer to learn reading and writing. Henry felt the friendship and protection of at least two men onboard the Triumph, Capt. Brintnall and Hubbard, sensing himself a fortunate young man at the start of his journey.

From Baja, loaded with about 50,000 sealskins,2 the Triumph sailed back to Hawaii for further provisions, providing the youths with a chance to return home, though both Hopu and ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia were determined to proceed on the voyage to China and America. In Macao, a well-established trading post for Europeans, Brintnall exchanged sealskins for tea, silk, cinnamon, and other commodities. The Chinese valued the under-fur of the seals to line winter clothes and were willing to exchange items of high value to New Englanders.3 The China trade brought extraordinary profits for all parties, even to the sealers who had the bloody and rancid work of killing and curing furs. After a six-month stay and the fulfillment of all regulations and protocol, including taxes and bribes, the Triumph left China in March, 1809, embarking on the last leg of the voyage through the Indian Ocean, around the Cape of Good Hope, into the southern Atlantic Ocean, and finally northward toward New York City, their home destination.

The Triumph’s arrival in New York City completed a 157-day voyage from China and two years from its New Haven departure. Formerly the budding nation’s capital, New York City in 1809 was a growing metropolis, second in population only to Philadelphia, the municipality that took its place to become the temporary home of the incipient United States government. Only the southern tip of 14-mile-long Manhattan was occupied. The rest of the island was made up of scattered farms and forests. However, residential buildings were quickly advancing northward, driven by population increase and fear of yellow fever; the most desirable locations were now located beyond Canal Street. Ferry boats crossing the Hudson River between Manhattan and Staten Island were stiffs or rowboats—one of the operators, a young Cornelius Vanderbilt. The new City Hall was in various phases of construction at the cost of an astounding half a million dollars. Two years earlier, Robert Fulton and Chancellor Livingston successfully ran their steam-powered Clermont up the Hudson River to Albany, marking the beginning of regular ferry service between the cities without the worry of tides, currents, and winds. Mayor Clinton DeWitt established the first public school with forty students in attendance, and the city had recently christened its second playhouse, the Bowery, to accompany the venerable Park Theater.4 The waterfront of lower Manhattan teemed with wooden sailing vessels, moored side-by-side, their masts rising like dense forests with leafless branches of yardarms jutting out from the shore. More ships, more buildings, and more people than Henry and Thomas could ever have imagined: New York overwhelmed them with culture shock and bewilderment, awed silence and mutterings in their Native language.

The timing of the Triumph’s departure and arrival could not have been more fortuitous. The ship left port prior to President Thomas Jefferson’s Embargo of 1807, designed to keep America out of the Napoleonic Wars by instigating economic hardships against England and France and as punishment to Britain for impressing U. S. sailors into the Royal Navy. The embargo halted all commercial sailing vessels going to and coming from the United Kingdom. The Triumph was able to obtain highly desired trade goods in China and return in time to be one of the first ships re-entering the port after the unpopular embargo was lifted. Needless to say, Brintnall found buyers to be plentiful in New York and received especially high prices for their cargo.

Once the Triumph docked and unloaded its valued goods, with the paid crew dispersed, the two young Hawaiians remained with Capt. Brintnall, accompanying him to his hometown of New Haven, Connecticut. Prior to setting out via Hell’s Gate and Long Island Sound, the boys were entertained in the city by two local merchants who invited them to attend a performance at one of the playhouses with its candlelit stage, proscenium, and celebrated orchestra. Henry and Thomas knew little of the English language and had difficulty understanding the show’s content other than interpreting the physical movements, facial expressions, and tone of the actor’s voices. Probably attending the newly-built Bowery Theater, they had never seen so many people in one “hut.”5

Their first real exposure to American culture outside life aboard the ship was overwhelming, loading them with so much information to decipher, “it seemed sometimes that it would make one almost sick.”6 The effects of culture shock heightened when the gentlemen brought the boys home for dinner. They had never seen so many rooms in one house and were especially shocked to see men and women eating at the same dinner table together,7 a behavior that never would have gone unpunished back on the islands.

Henry and Thomas’s acculturation persisted in the strangeness of New Haven where they were introduced to many new people, including young students from Yale College. They were readily accepted into Brintnall’s household as servants and were treated with utmost kindness. However, as men of color, they were considered “heathens,” socially defined as worshipers of pagan gods, possessors of limited intellectual potential, and containing the inherent possibility of becoming slaves. As servants, Henry and Thomas labored side-by-side with enslaved and free people of African descent, adding to their own curiosity of human biological variability. British-American New Haven society was relatively unfamiliar with Polynesians and remained challenged as where to place Hawaiians within their social hierarchy. Eventually, Thomas and Henry separated when Hopu was sent to live with the family of physician Dr. Obadiah Hotchkiss, Brintnall’s neighbor, while “Obookiah” remained within the captain’s household.

It was during these early days in New Haven that Henry once again heard the Christian Word of God, recalling his initial teaching by Russell Hubbard aboard the Triumph. At first, his English-language skills improved slowly, but the bright and inquisitive “Obookiah” longed for more formal learning. Hopu had begun to receive instruction, attending school with other students, but ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia had yet to be present at these tutorials. He was obliged to sit through Sunday service, understanding little of what the minister said, no matter how much he longed to comprehend. Was the congregation listening to the memorized verses of their traditional stories, as he had learned at the Heiau Hikiau? If so, where were the ki‘i, the wooden idols, and why didn’t the kahunas conduct their rituals privately behind wooden enclosures? Strange as the behavior appeared to him, his inquisitiveness sought knowledge and understanding of the peculiar behaviors of the haole.

An account from Thomas Hopu’s journal relates the story of young Henry weeping on the steps of Yale College. Approached by Edwin W. Dwight, a Yale divinity student and a relative of college president Rev. Timothy Dwight, concerning the cause of his distress, Henry cries, “No one will teach me.”8 The Memoirs of Henry Obookiah do not mention this crucial meeting in quite the same emotional manner, though ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia does state that Edwin approached him, inquired if he was the friend of Thomas Hopu, and asked if he also wished to learn how to read and write.9 Henry was eager, and Dwight assumed the role of his personal tutor.

At this junction in Henry’s emerging American cultural experience, Brintnall informed the boys of a ship preparing to sail out of New Haven for the Pacific Ocean, stopping at the Sandwich Islands. The captain assured both Henry and Thomas that should they wish to return home, he would provide for them to take the voyage. However, neither Hawaiian took the offer, desiring to continue in America longer to complete their education before returning home to their families. Moreover, ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia’s personal journey, though he travelled thousands of miles, was scarcely underway.

Henry took to his studies immediately, and once again proved a hard-working and intelligent apprentice. The New Haven community slowly began to realize that this young “heathen,” who in their cultural bias seemed at first so backward and uninspiring, had a huge thirst for knowledge and a heightened capacity to comprehend his teachings. He learned quickly, duplicating the arduous effort placed at the heiau, though many aspects of his training did not come easily.

Since there is no “R” sound in the Hawaiian language, Henry had difficulty pronouncing syllables containing the letter, which often came out like the sound of “L” when spoken in English. Edwin Dwight would repeatedly beseech him, “Try, Obookiah, it is very easy!” Henry took secretive delight whenever Dwight said this and eventually would turn the tables when Henry began teaching his mentor some of the habits and practices of his Native culture, specifically demonstrating to Edwin how to hold water and drink by cupping his hands. Adjusting the thumbs, clasping and bending the fingers together, ‘Opūkaha‘ia made an effective and natural drinking vessel with his hands. When his instructor attempted the maneuver, water dripped through his fingers onto the floor, frustrating the effort. Henry smiled, “Try, Mr. Dwight, it is very easy!”10

Edwin Dwight and others within the Yale community were becoming aware of Henry’s singular ability to entertainingly mimic the mannerisms of people around him. He would challenge, “Who dis?” and start to walk in a distinct style that imitated one of his new-found friends. With gales of laughter, his fellow students knew all the intended victims of Henry’s impersonations. When the New Englanders mimicked ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia’s gait, he fell to the floor laughing, “Me walk so?”11 He was becoming a favorite; his personality, humor, intelligence, and educational zeal endeared him to all he met in New Haven. His friends started to see him not simply as a curiosity from the pagan world, but an entrancing and unique individual with delightful personality characteristics previously unappreciated.

Henry’s intellectual training soon advanced to the point where he requested leave of Brintnall’s family to reside fulltime with the Dwight clan, accelerating his education and improving his chances of getting into an established school. The captain readily gave permission, and Henry moved into the home of the president of Yale College as a servant, continuing his secular and religious training. In Rev. Timothy Dwight’s household, he would be exposed for the first time to a true “praying family morning and evening.”12 It would mark the start of ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia’s sojourn throughout three New England states residing within many Christian households.

The Rev. Timothy Dwight IV had succeeded Ezra Stiles as the eighth president of Yale in 1795, born into a family with many ties to the college. Jonathan Edwards, credited with flowering the First Great Awakening, was his uncle on his mother’s side. Rev. Dwight was an enormous authoritarian figure in the church and college, at times derogatorily referred to as “Pope Dwight.”13 Teaching and the ministry were his vocations with ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia taking on the role of a rather special redemptive focus.

Although ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia did not fully understand all of the Dwight family’s Christian prayers, he could sense that they were at times praying for him and his salvation. They mentioned God to him often in daily conversation though Henry believed “but little.”14 After all, he had been training to become a kahuna, the spiritual conduit of his people where preparation had been intense and instilled with the knowledge of appeasement toward the many gods that controlled existence on the islands and possibly the world, including the lives of his American friends, though they seemed not to realize it. Instead, they prayed to their all-powerful, monotheistic God, strikingly different from the pantheon of Hawaiian akua, who had their own individual sources of authority.

Residing among the Dwight clan, the young “Obookiah” would learn of the “Great Awakenings,” religious revitalization movements that initially appeared in the American colonies during the 1730s. The “First Awakening” shook New England by storm. Powerful preachers like Jonathan Edwards convinced parishioners of their private guilt and the need to seek salvation through personal actions. To experience God in their own way required them to take responsibility for their own spiritual failures and acknowledge them through public penitence. This reduced the need for rituals, replacing the old theology with individual religious conviction.15 The First Great Awakening split the Congregational Church between Old-Lights, who strived to maintain the traditional orthodoxy, and New-Light revivalists attempting to return the church to its “original” orthodoxy.

Then, around the year 1800, an added wave of religious revival took form. While the earlier crusade concentrated doctrine exclusively toward church adherents, the “Second Great Awakening” sought to revitalize declining church memberships by accepting those outside the congregation into the fold, bringing thousands of new parishioners together in anticipation of the Second Coming of Christ, which they believed eminent. Church membership soared throughout New England, creating new denominations and sects. Significantly to Henry, the Rev. Timothy Dwight played an enormous role in helping to create and spread the spiritual resurgence.

The sky opened, cascading a powerful deluge. Lightning pierced the humid afternoon air, sending five young men running for the shelter of a nearby barn. The thunderstorm had disrupted their twice-weekly outdoor prayer vigil by a maple grove. Samuel John Mills, Jr., Harvey Loomis, Byram Green, Frances Robbins, and James Richards sprinted for the protection of the farm building to continue their invocation. Once sheltered from the torrential rain at the lee side of a large haystack, Samuel Mills, namesake and son of a leading Connecticut clergyman and a student at Williams College in Massachusetts, confided to his colleagues his maturing thoughts on spreading the Word of Christ to foreign countries.16

True to the concepts of the Second Great Awakening, Mills saw the necessity for missions to exotic lands: the call to arms to save the souls of the “heathen,” who would burn in hell simply for their lack of knowing the one true God. His companions instantly recognized the “truth” in Mills’ words and decided to band together as “The Brethren,” a secret society devoted to the promotion of the Protestant American foreign missions. Led by Samuel Mills, Jr., the “Haystack Prayer Meeting” participants would commit themselves to sharing their passion and evangelism for spreading the Word of Christ around the world.

While studying with Edwin Dwight, “Obookiah” met Samuel Mills, Jr., soon after the Haystack Prayer Meeting. On completion of his undergraduate work at Williams College, Samuel ventured to New Haven in pursuit of theological studies at Yale and, as a friend of Edwin, was poised to meet the young Hawaiian. Samuel, like many other students, became enchanted by ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia’s charm, envisioning in Henry’s intellect and resolve to learn, the validation of his emerging missionary reasoning. If this “heathen” had the mental capacity to comprehend the Bible, so could other Indigenous Peoples around the world. To Mills, this happenstance introduction to ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia was nothing short of Divine Intervention. If instructed and inspired properly, Mills reasoned, “Henry Obookiah” could serve as the foundation of the missions to his homeland. Samuel’s dreams and aspirations were now collected in the persona of this young Native Hawaiian. To further his ambitions and oversee Obookiah’s conversion, he proposed that Henry reside at his father’s farm in Torringford, Connecticut, to live within the context of a loving Christian home and receive personal instruction directly from the famed Rev. Samuel Mills, Sr.17

Henry’s friends thought the idea wise since they shared concerns that his continual presence in New Haven held the chance of his being kidnapped into the slave trade.18 With consent from Timothy Dwight, Henry willingly moved to the rural northwestern hills of the state in 1810. In Torringford, he would no longer be a personal house servant but instead was taught the work of the farm: cutting wood, pulling flax, and mowing hay for the Rev. Mills and his family, who found ‘Opūkaha‘ia “a remarkable youth.”19 He immediately felt welcomed and loved within the Mills’ household—“It seemed to me as my own home.”20

The physical journey of ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia extended over three quarters of the globe, westward from Hawai‘i to Connecticut. The spiritual journey seemed to be travelling as great a distance but remained far more uncertain. He had been exposed to a new cultural dimension, enduring some of the strange customs of these English Americans. Their clothing and food were relatively easy to adopt, yet their beliefs and worldview were alien to his kahuna training and were more difficult to accept. He wanted to please his new companions who treated him so warmly and took such great care of his physical needs. He certainly did not wish to disappoint them in his learning and acceptance of their ways. Rev. Timothy Dwight and Samuel Mills, Jr., seemed to have high expectations for him, making it clear that he had been purposely sent by their God to serve as the foundation for delivering the Gospel to his Hawaiian brethren. But he remained silently apprehensive and doubtful.

For a long while, ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia did not desire for ministers to approach him and talk about God. He hated to hear it.21 He had a deep desire to learn intellectually, not emotionally. He left the islands to remove a stigma, to set his mind with separate thoughts and pursue an education in the haole world. All the same, the pain remained. The cruel and violent deaths of his family, the captivity to the warrior who murdered his parents, the heartbreak and the loneliness even after he was reunited with his uncle, and the murder of his aunt had taken a toll. He recalled his hard days devoted to kahuna teaching and his uncle and grandmother’s disappointment at his sudden desertion. He had had enough of gods needing to be appeased.

John O’Donnell preceded our arrival at the cemetery the first morning of Henry’s disinterment. He had roped off a large area around the grave to keep anticipated spectators and reporters from getting too close to the edges of the burial excavation. The Cornwall Cemetery Association and the United Church of Christ brought a beautiful, decorative wreath set on an easel at the foot of the monument and placed flowers around its borders out of respect to ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia and his journey home. The American national and the Hawaiian state flags were placed in the ground at the head of the memorial. The tableau was lovely and tranquil.

Laying our hand-tools on the ground, the first order of business was the careful removal of shrine offerings and the inscribed marble headstone resting on the granite table. Flowers and flags were collected and all the offerings safeguarded. We slid the dry-laid tombstone gently forward off the stone table, securing its borders as if pallbearers, carrying the heavy marble down the hill to the cemetery’s storage vault to await restoration.22

The task of disassembling the granite table proved to be the most strenuous and time-consuming phase of the preparation. Dave Cooke had reviewed the monument the day before to determine the necessary field tools for dismantling. He arrived prepared with crowbars, wooden rollers, sledgehammers, four lengths of heavy chains, ropes, and a come-a-long.23 Careful use of a hammer and chisel by Will Trowbridge, our mason, loosened the mortar that bound the large granite blocks together. Placing the edge of the chisel against a seam, Trowbridge gently tapped the grout, crumbling enough space for a crowbar to be inserted into the crevice, gradually prying the blocks apart. Once released, the stones were carried downslope away from the gravesite although a few were so substantial they required the use of wooden rollers.

No mechanical equipment was used; every aspect of the work was performed by hand. Prior to removal, each boulder was photographed, sketched, and numbered to facilitate the monument’s stone-by-stone reconstruction. The interior of the table was not hollow but packed with mortar and smaller stones that also had to be carefully removed. The entire morning was taken with finishing this initial task.

Under the mortared granite table, we found a tier of dry-laid rectangular and rounded foundation stones supporting the aboveground structure. The largest stones were leveled at the lower foot area, providing greater downslope stability. These were measured, drawn, photographed, and removed. Once the stone layer was detached, we were surprised to find a second layer of foundation underneath, consisting of smaller flat stones with the largest supporting the upslope head region of the monument. Assuming we had finally exhausted foundation levels, we were astounded to encounter yet a third tier of stones resting well below the frost line. ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia’s memorial had been solidly constructed with three tiers of foundation providing reinforcement for the structure on its steep embankment, facilitating its survival for 175 years without shifting or pulling apart.

It was not until the mid-afternoon once all the stones were pulled away from the gravesite that we were able to erect a portable, aluminum-framed canopy to keep direct sunlight from contacting the anticipated skeletal remains. We cleaned up the bottom of the excavated area, leveled the floor and sidewalls, and rid the excavation unit of loose soil and stones that had toppled when the foundations were cleared. After all data, including soil samples, were taken from the exposure, a plastic tarp was laid out on the grass adjacent to the excavation unit. A hardware quarter-inch mesh screen was set up to sift excavated soils in case any funerary objects were missed during the excavation process.

Prepared for the disinterment, we commenced by slicing the soil thinly with flat, sharp-edged mason trowels to level the excavation and highlight differences in the coloration and compaction of the mottled earth. Soon a distinct outline of a hexagonal coffin appeared, confined at the head, expanding outward to the shoulders and tapering down to the narrow foot. We were at a depth of forty-two inches from the upper ground surface, and the configuration of the coffin was clear in soil coloration contrasts.

As we continued digging into the late afternoon, ominous dark clouds appeared in the west and were moving rapidly toward the cemetery. Within minutes we were engulfed by dangerous lightning strikes that preceded a violent thunderstorm. The crew hurriedly secured all the equipment into vehicles while I finished up the last level of the day under the canopy.

Amid lightening flashes, remains of the sideboards of the wooden coffin became exposed, appearing as a linear soil shadow of dark brown, decomposing wood and a pattern of hardware nails that would have held the top board in place. We were now working within the coffin and getting close to determining if Henry’s remains had been preserved. At this point, I didn’t want to stop though my heart pounded as lightening bolts flared overhead and thunderclaps deafened. Dave Cooke and I had made an earlier decision not to expose any skeletal remains this late in the afternoon. John O’Donnell arranged for overnight security, so I reluctantly climbed a short wooden ladder out of the burial unit, watched lightening hop-scotching the bordering hills, and anticipated tomorrow’s rendezvous with Henry ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia.24

The sweat beaded upon his forehead, seeping into his burning eyes. He swung the steel axe, repeatedly cutting wood for “Mr. F,” a neighbor of Rev. Mills amid the rolling hills of Torringford, stacking the logs between two small trees.25 The morning sun was relentless; the day already seemed long, the work tiring. Yet, ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia maintained his pace methodically, swinging the blade as he mimicked other field workers. Then he stopped. He experienced a rushing sensation overcoming him. His heart beat heavily; he felt weak, and in his rising anxiety a fearful thought occurred, “What if I die today, what would become of my soul? Surely I would be cast off forever.”26 His apprehension was followed by a voice that seemed to encompass him, “Cut it down, why cumbereth it the ground.”27 He gazed around. No one was within sight.

He dropped his axe and fell to his knees, looking up to the heavens, seeking help from “Almighty Jehovah.”28 Realizing now that he was nothing more than a “hell-deserving sinner” and that God had the right to thrust his wretched soul into eternal damnation;29 he deserved nothing less. He had ignored the Word though presented to him by many gracious and religious friends: Russell Hubbard onboard the Triumph; Edwin and the Rev. Timothy Dwight at Yale College; and now Rev. Samuel Mills and his son in Torringford—all of them had tried to save his soul. He had listened, yet refused to hear. Now he was pitiful.

‘Ōpūkaha‘ia lost track of the time spent on his knees in meditative reflection until removed from his revelry by another sound, the earthly voice of a boy beckoning him to lunch. At the Mills’ home, ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia picked at his food and looked forlorn enough for people to question the source of his apparent melancholy. He kept to himself, went to bed early, and laid awake most of the night, sorting out his emotions. He rose promptly the next morning before the others to find a place where he could be alone. Morning turned into afternoon, afternoon into evening. He did no labor, remaining distant.30

Troubled and searching inwardly, he recalled the long days studying with his uncle at Heiau Hikiau; learning the traditions of his people and devotion to the island akuas; beseeching the deities to intervene favorably in the lives of his people; and, honoring his warrior father and priestly uncle. Was he not Hawaiian? Could he commit to this religious conversion and worship the singular God of these British Americans? Or was he simply seeking the approval of these at times arrogant and pious Calvinists by adopting their rhetoric and mores? He did aspire to get religion into his head, intellectually, as a means of learning that much he understood. But ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia remained uncertain about allowing this new belief, this Christianity “into his heart.”31 He had felt the same struggle learning the disciplines of Lono and Kū. He studied, memorized, recited, and sought knowledge though coveted little emotional involvement. Having been traumatized in his youth, Henry blocked any passionate responses from his mind. Now, for the first time, he would consider an alterative conviction.

The revelation in the wood lot was sandwiched between trips to Andover, Massachusetts, attending Bradford Academy where ‘Opūkaha‘ia boarded in the Abbot household, a family he considered as pious as that of Dwight and Mills. His earlier attendance in Andover was marked by his refusal to accept any solemn feelings for the Christian God, however, after the wood lot experience, his second attendance at Bradford marked more resolve in learning Scripture. He now immersed himself in the Gospels, memorizing every story, every miracle. He absorbed his spelling book so he could write and read the Bible more proficiently. He learned and made rapid progress in his religious training, exerting the concentrated work he had shown when schooled by his uncle. He remained inquisitive; his willingness to learn saw no bounds.

What endeared ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia to the Abbot family was not simply his growing scholarship but also his “excellence of character.”32 Mrs. Abbot confided to a friend that Henry is “always pleasant. I never saw him angry. He used to come into my chamber and kneel down by me and pray. Mr. Mills did not think he was a Christian at that time, but he appeared to be thinking of nothing else but religion. He afterwards told me that there was a time when he wanted to get religion into his head more than into his heart.”33

With renewed diligence in his Bible study, Henry began to submit to the devotion of the Christian God. Heartfelt and sincere were his new feelings, no longer simply academic. With the fervor of a convert, he began to see his kahuna knowledge as irrational. He would tell a fellow Hawaiian, “O how foolish we are to worship wood and stone gods; we give them hogs and cocoa nuts and banana but they cannot eat.”34 Once ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia threw off the veil of his youthful training in the polytheistic religious beliefs of Polynesian Hawai‘i, he was free to embrace Christian salvation. We can only imagine how hard it must have been to release the cultural beliefs of his ancestors; disregard what had been taught him during his childhood; denounce the pantheon of akuas instilled into him during his training at the heiau. It required a revelation, but once released, he reformed in both mind and spirit. “In my secret prayer and in serious conversation with others…I thought now with myself that I have met with a change of heart.”35

While at Bradford, ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia learned that another Hawaiian lived in the vicinity of Andover. Seeking out his fellow Kanaka Maoli, Henry stayed a full day and evening in his company. Neither of the boys slept that night. Instead they lay awake, talking in their Native language until dawn. When asked later what he had learned from his companion concerning news from Hawai‘i, ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia replied, “I did not think of Hawaii. I had so much to say about Jesus Christ.”36 He had truly been reborn, converting to the “one true God” and setting seeds for his actions and words as a future missionary.

In the spring of 1812, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) appointed Rev. Samuel Mills, Jr., to travel through the Mississippi Valley, surveying those areas for future missionary efforts among reservation Indians and plantations of African captives.37 Soon after Mills’ departure, ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia would spend time in Hollis, New Hampshire, where his newly-won belief would provide its first test of faith through an ordeal of sickness.

The fever appeared to come on suddenly, leaving ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia frail and bedridden for five weeks. In Hollis he would live within a number of households including that of the Deacon Ephraim Burge where the sickness overcame him. Dr. Benoni Cutter presided over his young patient, praying with him many times. All in Hollis feared that the “Obookiah” they cherished in their thoughts of his complete devotion to God would be taken from them before his salvation could be secured. Mrs. Burge inquired of his willingness to die and leave a world of sin, “Do you remember the goodness and the kindness of God towards you?” ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia answered in the positive, “Yes, for I have neither a father nor a mother, nor a brother nor a sister in this strange country but He. But O! am (sic) I fit to call him my Father?”38 Often ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia felt alone and meaningless, affected by his survivor’s guilt. “Many times I meet with the dark hour.”39

He was able to fight off the fever and despair, regain his footing, and find a loving and forgiving “Father,” one who truly cared about this “Henry Obookiah” and represented the head of his spiritual and earthly family. Within the short time he was in Hollis, he would go through the conversion for which New England had prayed. It was here that “Henry’s heart was renewed by the Holy Spirit.”40 With his physical and spiritual state bettered, Henry would leave Hollis, return to Andover, and eventually go “home” to Torringford,41 where he would take one further giant step in his transformation to realize the meaning of his journey.

When Samuel Mills, Jr., returned home from his two-year missionary tour in the early summer of 1814,42 he inquired about the state of young ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia’s Christian learning. He was gratified to hear that Henry was giving his life to the Lord and continuing his spiritual and academic training with friends and tutors in Litchfield, but what he found just as gratifying was the acknowledge that Henry was translating Hebrew chapters of the Bible phonetically into the Hawaiian language. In doing so, he compiled a dictionary and a grammar book, and by 1815 maintained a diary of his personal development. Henry wrote and memorized the Bible similar to his kahuna training, so that when Mills arrived home, he found ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia in the midst of an immense emission of creative intellectual energy.

With his continuing education, Henry’s confidence developed. He began to speak in public, took on the learning of Latin, Hebrew, geometry, and geography while continuing to work on his English. He started to write an increasing number of letters, even beginning a personal memoir telling of his youth in Hawaii and his journey to New England. Now in his twenties, Henry’s heartfelt enthusiasm for all things scriptural provided a personal joy and triumph for the Mills family.

Henry was also physically maturing into a formable young man. Edwin Dwight describes him as being above the ordinary size of young New England men, standing just less than six feet in height with limbs and body well proportioned and large. At sixteen, ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia had been regarded as “awkward and unshapen” (sic.), but now he appeared “erect, graceful and dignified.”43 His skin was described as olive in coloration, a mixture of dark African and “red” Native American complexions. His black hair was cut short and his clothing westernized. His nose was prominent and his chin projected.44 There was no questioning his “otherness” when he mingled in the company of British Americans.

If Henry stood out physically, his personality and character also separated him. “In his disposition, he was amiable and affectionate. His temper was mild. Passion was not easily excited, nor long retained. Revenge or resentment, it is presumed, was never known to be cherished in his heart.”45 ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia was considered a good and reliable friend, always grateful for favors bestowed upon him and, most tellingly, he felt an ardent affiliation toward the various Christian families with whom he resided.

Through Henry’s conversion, intellect, and personality, Samuel Mills, Jr. could now envision the formulation of “The Brethren” plan. ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia would be the bridge to the Hawaiian missions—a bridge that would span the oceans; a bridge over which Mills and other missionaries would walk across to bring salvation to the “pagans” of the Pacific Islands. With Henry’s noticeable development, Mills and Adoniram Judson took the opportunity to present a formal letter at a meeting of Congregational Church leaders seeking permission to organize a missionary effort consisting of both New England men and women accompanied by Native youths returning to their homelands in the spirit of Christ. The church leaders deliberated. The fulfillment of the “Second Great Awakening” beckoned; the timing was ripe. Support was given to The Brethren plan and the Foreign Mission School was born. A powerful vision was formulated: Henry “Obookiah” would complete his journey home accompanied by Samuel Mills, Jr., and together they would replace the kapu system with the Gospel of a loving God.

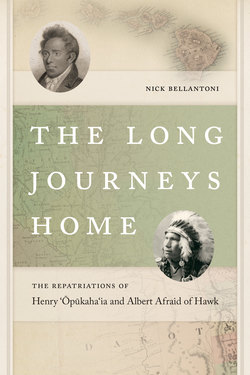

Frontispiece Portrait of Obookiah, engraver unknown, 1818, from Memoirs of Henry Obookiah, A Native of Owyhee and A Member of the Foreign Mission School (New Haven: Office of the Religious Intelligencer.) National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

‘Ōpūkaha‘ia, heartened by his new confidence in the Holy Spirit, found the courage to petition the North Consociation of Litchfield County to take him under their care and provide counsel and direction into his life.46 The Consociation voted overwhelmingly in his favor and appointed a three-person board to supervise his education. Now focused, dedicated, and resourceful, Henry was being prepared for meaningful accomplishments and, with discussions of developing foreign missions, a possible reunion in Hawai‘i as a budding Christian kahuna.

Though the thought of a Hawaiian homecoming had never been far from his consciousness, he had seen no earlier purpose to it, not when the meaning of his journey had no full perception. Yet returning as a Christian missionary to spread the Word of his newfound “Father” and paving a path to salvation for his brethren would be the fulfillment for which he was striving, the reason to go home. He had a message to share, a message that demanded to be heard—a message that would save Hawaiians from the pangs of hell and fold them into the arms of their benevolent protector, their Father who would love and care for them. Henry had searched for and found a family to replace the one he had violently lost. “I have neither a father nor a mother… but He.”47 Invoking his Native beliefs in the comingling of the supernatural and natural worlds, ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia viewed Jesus as a biological Father, as real as Keau. For years he had probed his mind for the reason why he was the lone survivor of all the ferocity forced on his family and for the agonizing guilt associated with complicity in their suffering. He now had an answer and a joyous reason for a homecoming.

‘Ōpūkaha‘ia sought the strength to speak of his new desire. To a Native friend, he broached the subject, pleading with his companion to accompany him to Hawai‘i. Getting no encouragement, he suspected that his confidant might be influenced by the fearful consequences of attempting to introduce a new religion to the Kanaka Maoli. “You fraid?” Henry asked. “You know our Savior say, ‘He that will save his life shall lose it; and he that will lose his life for my sake, same shall save it.’”48

In April of 1815, ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia expressed his desire to become a formal member of an established church, and with the support of the senior Rev. Samuel Mills, Henry was received into the Church of Christ Congregational in Torringford.49 However, dissatisfaction resulted among many parishioners when Mills sat Henry and other Hawaiians in his own pew in front of the New England worshipers. The church had previously remodeled slave pews located in the gallery over the stairs, an area boarded-up so high that people of color would not have to be tolerated by the white assembly below.50 Mills rejected the idea of separation for the Hawaiians and had them seated prominently with him, much to the dismay of other church members.

By this time, “Father” Mills, as Henry called him, bestowed upon ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia all of the love and compassion of a true son. His powerful influence on the community gave the young Hawaiian a foothold into the congregation. Rev. Mills was a tall, well-proportioned man with a large face and round head. His eyes were bold, yet benignant. He was stately and gave his finest appearance standing at the pulpit. At times when he preached to the people attending worship, his religious themes seemed to border on the oddity, and his expressions would often solicit a smile, sometimes even provoke laughter. The great themes of Father Mills’ life were “souls and salvation,”51 and ‘‘Ōpūkaha‘ia was his spiritual son, loved as much as Samuel Mills, Jr., his biological son.

Venturing back to Amherst, Massachusetts, at the end of 1816, Henry lived with Rev. Nathan Perkins, an agent of the ABCFM. The board was moving forward in establishing a special “Foreign Mission School,” commonly referred to as the “School for Heathens,”52 choosing Litchfield County as its home since many of the Hawaiians and other potential candidates lived in the area, and it was situated away from the temptations and dangers presented by big city life. In his association with Perkins, Henry commenced a speaking tour through New England for the purpose of soliciting donations for the benefit of the “Heathen School.”53

The prevailing debate throughout Congregational New England and elsewhere among British Americans was whether the “heathen” possessed the mental capacity to comprehend the Bible, let alone preach it. This being unsure, previous financial and spiritual support was relatively lacking. “Obookiah,” with his personality and intellect, would change many minds about the scholarly capabilities of Indigenous Peoples and, consequently, untie many conservative purse strings. Reverend Perkins noted that wherever Henry travelled, “he was much beloved.”54 Visiting many towns and speaking to church congregations, Henry addressed his conversion and his knowledge of Christianity, never failing to impress. He always presented himself appropriately, solemnly, and interestingly. He aroused New Englanders, who had no expectations for the missions, to become satisfied that conversion of the “heathen,” by the “heathen,” and for the “heathen,” was attainable, even practicable.

Henry’s narratives of his fellow Hawaiians worshiping a multitude of gods, all manufactured from wood, and of priests performing rituals involving human sacrifice, convinced Congregationalists that the need to teach Christianity there was truly great. Dollars poured in. This “Native of Owhyhee” had lifted the dispositions of these fundamentalist, “cold” New Englanders to consider the propriety of “heathen” missionaries. He changed many minds, shattering many misconceptions, and parishioners eagerly reached into their pockets to contribute. In effect, Obookiah was already a missionary, converting, in this case, Congregational New Englanders to the confidence of his cause.55 His effect was all that the American Board of Commissioners could ever have hoped for.

With the donations Henry solicited, the Foreign Mission School became a reality. “Obookiah” would be the inspiration, the first student, the model, carrying the bursting excitement and expectation of Congregational New England on his broad shoulders. The time was approaching for ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia, accompanied by the leadership of Samuel Mills, Jr., to bring the Word and carry the “Cross” over the seas to deliver eternal salvation to his fellow Hawaiian islanders.

With an early start to the second day of the exhumation, I stepped onto a short wooden ladder descending more than four feet into the burial unit and balanced once again on the slender dirt platform prepared as my workspace. Ropes were tied to the handles of plastic buckets to hoist excess soil out of the grave shaft and through hardware mesh screens manned by our volunteers and students. I arranged my hand tools—primarily trowels, brushes of various sizes, bamboo picks, a small spatula, and dustpan—underneath my body as I hunched on all fours. The first task was to clean up the effects of the past evening’s thunderstorm. Once I removed the tarp that covered the excavation unit from the rain, the damp, eroded earth had to be leveled and crisply cut to restore the configuration of the hexagonal coffin established the day before, allowing accurate measurement: six-and-a-half feet in length, with widths of one foot at the head board, ten inches at the foot, and twenty inches across at the shoulder.56

Excavating within the coffin boundary, brass tacks and black painted hardwood appeared along the sideboards in the area of the chest cavity. My initial impression was that the tacks were aligned to the sides of the coffin to secure a decorative cloth lining the interior; however, it soon became apparent that they had been hammered into the coffin lid, which had split down the middle, compressed to the sides by earth pressure. The coffin was hardwood, painted black, and except for where the brass tacks neutralized adjacent soils, no other wood survived other than as soil shadows. When the reconstructed coffin lid was mended, the brass tack pattern yielded “H. O. AE 26” enclosed in a heart-shaped motif which are interpreted as the initials of the person lying in the coffin, the Latin “A.E.” for “age of,” followed by the age at death with the heart signifying a sign of Christian endearment. Even without knowing the story of “Henry Obookiah” in New England, the physical evidence of the coffin strongly suggested that the person lying here was very much loved by his contemporaries.

Small, broken fragments of window glass, some twenty in all, were encountered in the region of the cranio-facial complex, establishing that Henry’s coffin contained a viewing glass, allowing mourners to observe his face during the 1818 funeral without having to lift the entire lid. The glass also prevented mourners from cutting pieces of clothing or hair as memorial artifacts. The painted hardwood, brass tacks on the lid providing the deceased’s initials, and a viewing glass over the face represented innovative mortuary designs for early 19th century coffins and reflected state-of-the-art funerary technology for its time. The entire burial complex suggested the high status and importance given to the deceased; little expense57 was spared to give Henry a monument that would perpetuate his memory for a long time after his death.58

The first evidence of skeletal remains was the frontal bone of the forehead, the highest elevated area when the body is supine, which exhibited limited cortical loss for its age and suggested that the rest of the skeleton should possess excellent organic preservation. Excavation proceeded at the superior portion of the skeletal anatomy, concentrating on exposing the high points and maintaining horizontal control. Delicately I brushed around the broken pieces of glass to maintain their positions and reveal the face. Henry slowly emerged before me, the very image of his portrait.

Concentrating on the subtle work at hand, I had not noticed or heard the increasing assembly of bystanders that had accumulated in the cemetery to observe the disinterment until I rose to stretch my legs, giving myself a moment’s reprieve, eager to avoid carelessness through fatigue. As I stood, my shoulders were level to the ground surface where I could see more people gathered than had been there on the previous day, many more, possibly forty or so. While our crew was busy with the responsibilities of the archaeological excavation, I placed a damp cloth over Henry’s face to keep the fragile bones from drying out in the heat, but also out of respect, so public eyes could not gaze upon him.

Wooden coffin lid of Henry Obookiah, exhibiting brass tack patterns of his initials and age of death, outlined in a heart-motif. (Courtesy Bill Keegan.)

Ascending the ladder, I was immediately met by reporters covering the story for Connecticut newspapers. I emphasized immediately that no published photographs of Henry’s remains would be tolerated. Also present at the cemetery were members of the repatriation team including Henry Fuqua and Rev. Carmen Wooster. My reprise from excavation was spent satisfying the role of public relations director and educator, repeatedly explaining our procedures, methodologies, and findings to the various communities present.