Читать книгу The Long Journeys Home - Nick Bellantoni - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1 | “Oh, How I Want To See Owhyhee”

His dry, hacking cough could be heard throughout the large, two-story colonial saltbox that served as the parsonage of the Rev. Timothy Stone, pastor of the South Parish in Cornwall, Connecticut, a picturesque town tucked in the state’s Litchfield Hills. The entire Stone family, along with four of his Native Hawaiian (Kanaka Maoli) companions, stood witnesses to the violent attack on his body, but could not feel the intense pain of his muscles or the severity of his headaches. The young Hawaiian Christian man, Henry “Obookiah,” lay in bed during a cold, bitter New England February in 1818, surrendering to the ravages of typhus fever, far from his warm island birthplace. Henry had been studying at the newly formed Foreign Mission School with hopes of returning to Hawai‘i with the Gospel of Jesus Christ in his hands. His early death would steal the opportunity.

Throughout his month long illness, Henry’s attitude remained steadfast, patient, even cheerful at times, and above all resigned to the Will of God. Mrs. Mary Stone, who took it upon herself to care for Henry on his deathbed, read the Bible and pray with him daily, was impressed with his Christian conviction. Near the end she inquired if he thought he was dying, and Obookiah responded in the affirmative, weakly uttering, “Mrs. Stone, I thank you for your kindness.”

Fighting back tears, she responded, “I wish we might meet hereafter.”

Feebly, he assented, “I hope we shall.”1

When asked if he was afraid to die, Henry cried, “No, I am not. Let God do as He pleases.” Then again, he so desperately wanted to live. Live to be a powerful witness to the one, true God. Live to bring salvation to his people. Live to see Hawai‘i. “Oh, mortality!” he cried out one night.2

Insisting that his Native companions remain close to him during his ordeal, he beseeched William Kanui, fellow-student at the Foreign Mission School, who also nursed ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia during his sickness, “William, if you live to go home, remember me to my uncle.”3 Bursting into tears and raising his hands heavenward, Henry lamented, “Oh, how I want to see Owhyhee!”4

His approaching death was peaceful. He seemed to be free of pain for the first time in weeks. With his compatriots beside his bed, he spoke in his native language, “Aloha o‘e”—My love be with you.5

Damp with perspiration, the cotton shirt clung to my back as I hunched on hands and knees over a narrow dirt base leveled at almost five feet into the earth alongside the burial. But it wasn’t until the moisture gravitated onto my nose, dripping to the ground below that I truly appreciated the July heat and humidity that had descended onto the small knoll in Cornwall Center Cemetery that summer morning in 1993. The stage from which we excavated was only a foot wide at the head area, leaving sparse room to maneuver beside the grave, necessitating balance and concentration to gently scrape away earth while not impacting the fragile skeletal remains hidden under mere inches of loose sandy soil.

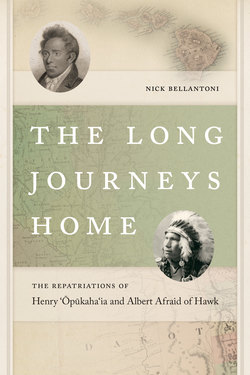

Portrait of Henry Obookiah. by Adelle Summerfield, n.d. (Courtesy of Author).

The anticipated skeleton would, hopefully, be the remains of ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia, the first Christianized Native Hawaiian—the young man whose untimely death in 1818 inspired missionaries to venture off to the Sandwich Islands, charged with converting the “heathen” who up to that time possessed no knowledge of Christ; whose intelligence had created a phonetic Hawaiian alphabet which he applied to translate the book of Genesis from Hebrew; whose personality and cogent arguments for allowing Native men to save Native souls led to the development of the Foreign Mission School; and whose life and death story would be told in Sunday Schools to this day. His New England Calvinist patrons gave him the Christian forename of “Henry” while spelling and pronouncing his Hawaiian birth name “Obookiah.” As Connecticut state archaeologist, I was given the responsibility to conduct the professional and respectful disinterment of his physical remains per the request of his genealogical relatives for repatriation home to Hawai‘i. After almost two centuries in New England soil, the best we could hope to recover would be a decomposing skeleton.

Our archaeological field crew had already removed the heavy marble tombstone engraved with the epitaph of “Henry Obookiah” off a granite table marking the burial. The stone monument had also been systematically disassembled, as were three layers of supportive foundation, which extended well below the frost line. Thinly slicing through mixed-mottled sandy soils with the sharp edge of a mason trowel, I encountered the first evidence of the top of the coffin at fifty-two inches below ground surface when rusted metal hardware appeared. The horizontal pattern of nails revealed a hexagonal-shaped box laid in a classic Christian mortuary practice where the deceased was reposed supine with head oriented west, facing east, which means that as one reads the epitaph on a historic New England tombstone, the deceased is not in front of the stone, as most people suspect, but behind it with their feet moving away. Accordingly, on the Day of Resurrection, the dead would be able to witness the rising Christ coming up with the sun and awaken to join Him in everlasting life.

Further evidence of the wooden coffin became visible when a thin, dark, linear stain appeared, a decomposing shadow of the sideboards. Though all that remained of the wood was soil discoloration, it provided a clear outline to the coffin. Excavating within, a pattern of brass tacks with preserved wood adhering materialized along adjacent sides about the chest area. My initial impression was that the tacks secured a draped cloth or decorative linen lining the interior of the coffin. But as I carefully continued deeper into the side margins, the tack pattern changed, descending downward as we dug toward the pelvic area. A second row of brass tacks underneath the discovered row on the right side of the coffin also became visible, forming a semi-circular pattern like a half moon; on the left side, the second row tack configuration emerged but took on a dissimilar shape, horizontal.

As more of the arrangement was revealed, it became apparent that the wood and tacks were not associated with the sides of the coffin, but were actually part of the lid. When the overburdened soil collapsed into the decaying coffin interior due to weight pressure from the foundation tiers and monument above, it split the decomposing top board down the middle, filling the coffin housing with sand and compressing the lid along the sides like swinging a downward, horizontal gate. Brushing the edges revealed that the brass tacks patterned an “H” on the left side and an “O” on the right. “Henry ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia!” I thought to myself, smiling.

Our mandate was to remove for repatriation the remains of “Obookiah,” and his remains only, so we had to be unconditionally certain that this was his grave and not that of another individual. Though we had yet to encounter skeletal remains, the brass tack pattern of initials was an optimistic first indication. We were confident now that this was his coffin, but would there be any associated remains? Acidic soils are the bane to organic preservation in New England. So we tested the sandy ground for its pH content, which fortunately yielded a relatively neutral reading (6.8), suggesting less acidity than we normally find in Connecticut’s mixed-deciduous and high precipitous environment. We remained hopeful.

Then, moving my trowel gently over the soil leveling the head region of the coffin, I heard a dulled tone. Immediately thinking I had encountered a small stone or another metal coffin nail, I put my trowel aside and grasped a small, fine-hair paintbrush among the various hand tools gathered under me. The material encountered felt hard, too hard for bone that had been in the ground for 175 years, I thought, but as my brush swept the granular soil aside, uncovering a one-inch diameter circle, I recognized the rounded structure of the forehead. My God, he is here, I realized, and his skeletal remains were firm, unusually well preserved for a grave of this time period.

An array of anxious people had aligned above me, peering down into the excavation unit, attempting to see over my shoulders, but from their perspective they could only distinguish a small, unidentifiable brownish speck where I had been excavating. I could hear the responding buzz of excitement and anticipation from the onlookers, but before resuming the process of exposing more of the cranium, I allowed myself a moment to appreciate that I would soon be the first person since his death and burial on this sandy knoll in 1818 to look upon the facial structure of Henry ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia. From the scant part already exposed, I realized that we would recover his intact skeleton, bequeathing his repatriation to his awaiting Hawaiian family. I remember thinking to myself, “Henry will return home.” Also aware that the attending crowd stood clueless as to what had been discovered, I turned my head over my right shoulder, looked up and gave identification to the emerging speck: “He’s here!”

The Hawai‘i ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia longed to see once more rose from the depths of the Pacific Ocean thirty million years ago when vents on the ocean’s floor developed a crack or hot spot through which poured molten lava from the earth’s mantle. For tens of millions of years, subterranean liquid rock slowly seeped and spurted, gradually accumulating layer upon layer, until eventually emerging from the sea. Beginning from the northwest end of the rupture, small islands, beginning with Kure, reached the surface of the ocean. This continuous volcanic process created the five largest islands: Kaua‘i, O‘ahu, Moloka‘i, Maui, and Hawai‘i (The Big Island) to the far southeast. The outgrowth is a series of 122 forming islands along a chain spreading out for almost 2,000 miles.6 That is the western scientific explanation. Contrarily, Native Hawaiian tradition relates that the islands were born like humans, conceived by their parents Papahānaumoku, who gave birth to the archipelago with her partner, Wākea, the sky father.7 Together, they genealogically connect the Hawaiian people to their beautiful islands, perceived as relatives, giving rise to the powerful Hawaiian love of their land (aloha āina).8

These nascent islands with their barren topography would welcome hundreds of species of plants and animals that somehow found their way through wind and water. Lichen and moss grew as factors of wind and rain pulverized the lava into bits of soil. Birds came feeding on fish, depositing their digestive waste containing seeds, which germinated and grew. Insects, blown by jet streams, found the cooled lava their home. Coral and mollusk larvae as well as seaweed surfed the bounding waves from other Pacific islands reaching Hawai‘i and setting their roots along shallow inlets. Storm swept seeds, drifting logs, and branches of wood found their way.9 Within this emergent island ecology, life adapted and developed untouched by human hands until the first Polynesians ventured forth.10

Hawai‘i’s founding Polynesians sailed in large, double-hulled canoes, some seventy to eighty feet in length, lashed together affording a platform that carried sixty or more people, as well as water, household goods, animals including pigs, dogs, and chickens, and vegetables and fruits such as bananas, taro, and coconut.11 Their seafaring crafts were floating communes, probably the swiftest ships in the world 1,000 years ago. So intrepid and warlike were the Polynesians that they have been referred to as the “Vikings of the Pacific.”12 How their flotillas ranged the great expanses of the Pacific Ocean, at least 2,000 miles from the Cook Islands and Tahiti where they had presumably journeyed from, when they had no knowledge of the lands before them, is a wonder of human history. By the time they approached Hawai‘i, they had already inhabited almost 290 far-reaching islands, spatially the widest spread cultural population in the world.13

Whether these valiant voyagers came through single or multiple migrations also remains unknown. Undoubtedly in their voyage(s) they were confronted with massive storms, exposure to wind, rain, along with the harsh effects of salt water and sun. They had to take into account the doldrums, an equatorial regional phenomenon where the trade winds converge and flow upward instead of horizontal, leaving them becalmed in a windless sea, straining their self-propelled rowing energy as well as food and water supplies. Even so they persisted. Faith in their ancestors and gods, along with their vast knowledge of oceanic and island worlds, they travelled great distances without the use of navigational instruments. Rather, they closely observed the sun, nightly stars, patterns of waves, cloud formations, and the behavior of dolphins and birds to direct them to new islands. They had to be fearless and faithful and courageous.

Survival of these intrepid Polynesians depended on all family members, ‘ohana, working closely together, developing strong bonds and dedication to each other. Most likely driven to inhabit new islands by population pressures, limitations to environmental resources, and cultural tension, Polynesians, astride their “village” canoes, eventually attained the northern apex of the Pacific Triangle.14

Upon Polynesian arrival, Hawai‘i contained no carnivorous mammals or snakes; rather, they found flightless birds with no natural predators to defend against. Fish, coral, and underwater plants abounded off shore; onshore, flowers bloomed. But other than the fish in the water and birds in the sky, there was little for humans to digest. The plants and animals they brought with them would have to bear fruit and offspring to secure their long-term survival. Serene as this Eden-like world might appear, it had immense dangers: volcanic eruptions, tsunamis, hurricanes, and earthquakes—all of which could strike unexpectedly and suddenly.

To deal with these calamitous events, the southern Polynesians brought to the northern islands concepts of their many deities, who needed to be appeased through rituals and behavioral taboos maintained by the chiefly ali‘i class, who were supported by a social system based on genealogical rank, to ensure balance and harmony in their unpredictable world. Travelling with them were Kāne, the Creator; Pele, the goddess of fire and volcanoes; Nāmakaokaha‘i, the goddess of the sea; Lono, the benevolent god of fertility; and Kūkā‘ilimoku (Kū), the fierce god of war. The island’s formation was one of fire and water (Pele and Nāmakaokaha‘i), providing cogent dichotomies of form: liquid and solid, seaweed and plants, fish and birds that enhanced their worldview.15 These gods (akua) were spiritual, powerful, and dangerous—considered physical ancestors who partook in the ocean voyages and brought social stability to the newly-founded islands. The akua provided life, but could just as easily cause death. They were both feared and loved by the Kanaka Maoli (Native Hawaiians), hence worthy of worship.16

Deities, as all things animate and inanimate, contained mana, a powerful and vital life force. Mana could be obtained by humans through genealogical descent, through the killing and sacrifice of an enemy, as well as peacefully through personal relationships and altruistic accomplishments.17 So sacred and powerful was mana that laws and restrictions, kapu, had to be instilled to maintain order, or evil and disaster could attach itself to the people. To maintain balance and harmony, the sacred kapu system provided a set of behavioral do’s and don’ts. Akin to the Tahitian tabu, kapu encompassed many prohibitions, such as fishing out of season, walking on a chief’s shadow, and the exclusion of men and women from eating together. If broken, violators could be put to death to protect the whole world; exoneration could only come from a kahuna or the reaching of a pu‘uhonua, a place of refuge.18

Polynesian chiefdoms represented a level of political complexity based on concepts of hereditary inequality19 with the chief representing a formal office within a ranked society including commoners and a servant class. As their populations grew, competition for limited productive farmland and other natural resources lead chiefly families to obtain, usually by force, suitable agricultural territories to which they would hold title. The common people (maka‘āinana) would receive rights to farm the chief’s land, sanctioning the chief’s authority over natural resources, wealth, and regulation of labor. The ali‘i nui (high chiefs) maintained social control by making judgments, resolving disputes, and punishing wrong doers as well as enforcing and creating kapu. While the chief’s word was law with the power of life and death over commoners and servants, these social relationships benefited all the Kanaka Maoli by maintaining harmony and equilibrium within their world.

Since ancient Hawaiian society was an oral rather than a written culture, values and history were learned through trained storytelling, which was considered sacred. Developed hundreds of years before contact with the Western world, the Kumulipo consists of chants and songs that tell a creation story of the universe and the Hawaiian people from the time of darkness to that of daylight. The Kumulipo provide a vast cosmological genealogy that stresses the relatedness of the entire world: the land, the gods, the ali‘i, and the maka‘āinana, who are all closely and affectionately connected as ancestral kin, all descendants of Wākea and Papahānaumoku.20 Only through a full understanding of their great genealogy are the ali‘i able to assert their chiefly rank. The natural and supernatural worlds are one and the same with no distinctions. Hawaiians share a lineage with all of creation.

How to respond to this complex worldview was the role of the kahuna. These priests gave order and guidance; consoled and healed; advised when to plant and harvest; instructed when to fish; ordered to war or to remain at peace; conducted sacrifices and rituals; and proffered penance and forgiveness to breakers of the kapu. To appease the gods and maintain stability of the ali‘i, kahunas carved the spiritual wooden ki‘i (images) and oversaw the building of elaborate heiaus (temples) where offerings were issued to the divine, sometimes through human sacrifice.21 From the practical to the spiritual, the powerful kahuna, holding their ceremonies on stone pyramids in private wooden enclosures, were the vital life force of the Hawaiian people.22 The teenage ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia would be trained by his priestly uncle, tutored at the Hikiau Heiau at Kealakekua Bay, Kona, to become such a kahuna, translating the Kumulipo and other sacred legends for the Kanaka Maoli.

It was there, in 1778, a decade before the birth of ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia, that Hawaiians had greeted the British sea captain James Cook. Although other foreign populations may have made earlier contact with Hawai‘i, it was Cook’s encounter that brought the awareness of the islands to Western societies. The Hawaiian Islands would never again be isolated from the rest of the world; the period of being totally Native, Oiwi Wale, had ended forever.23

After the arrival and subsequent death of James Cook at the hands of the Hawaiians, the appearance of British and American sailing vessels was less frequent due to the Western world’s concern regarding the perceived ferocity of these Native people. However, as time passed and with the recognition of the islands’ strategic midway location in the vast Pacific Ocean, the sight of European and American sailing ships, whaling and merchant, became commonplace. One ruling chief who welcomed these foreigners was the tall, physically thickset, young adult ali‘i, Kamehameha.

Kamehameha had greeted James Cook on his initial arrival to Hawai‘i and even boarded the HMS Resolution to trade and have dinner with the British sea captain. Recognized as exceptional among the chiefs, Kamehameha appreciated the usefulness of steel weapons obtained from Western traders in military warfare, especially against his enemy’s stone and wooden armaments. Employing these newly available technologies, Kamehameha launched a campaign for domination of the Big Island and, once achieved, the unification of the entire Hawaiian archipelago under his absolute rule.

According to ancient legends, a great chief would be born with the appearance of a shooting star, and that chief would unite all of the islands under his reign. In 1758, the year of Kamehameha’s birth, Halley’s Comet passed prophetically in the night sky. He was the son of Keōua and the grandson of Keaweikekahia-liikamoku, a former ruler of the eastern portion of the Big Island. Upon his birth, a kahuna of standing prophesized that one day this newborn would become a Mō‘ī, Ali‘i Nui (King, holding the highest of chiefly ranks) of the entire island.24

Since his family kept him isolated in the mountains during his youth out of fear that jealous chiefs might take his life, and due to his introspective behavior, Kamehameha was labeled “The Lonely One.” His uncle, Kalani‘ōpu‘u, Mō‘ī of the Big Island, who welcomed Captain Cook to Kealakekua Bay, brought Kamehameha back from exile and bestowed upon him the trademarks of a nobleman with a feathered helmet and cloak. The young man grew in strength and wisdom, was tutored in the arts of combat, and known for his courage in battle.

In traditional Hawaiian society, whenever an ali‘i nui died, his successor had the right to redistribute land and other valued resources, which meant that competitive conflict would breakout between contenders for vacated, exalted positions. When Kalani‘ōpu‘u died in 1782, Kamehameha competed with the ali‘i nui’s two natural sons, Kīwala‘ō and Keōua, over control of the chiefdom. Kīwala‘ō attempted to placate Kamehameha by naming him the caretaker of the war god, Kū, and making him the chief of the luscious and productive Waipi‘o Valley. Unfortunately, this did not satiate the ambitious Kamehameha. Warfare broke out between the cousins. Kīwala‘ō was killed at the Battle of Moku‘ōhai, and Keōua was declared the new High Chief.25

With the advantage of muskets, swords, and cannon obtained from European and American trading partners, Kamehameha warred continually with Keōua for four years. Yet the steel weapons gave no immediate benefit against the aggressive son-chief who had a large following. Feigning a desire to end the continual conflict, Kamehameha invited the suspicious Keōua to a peace parlay in early 1792, which the High Chief, whose resources were being exhausted by the incessant warfare, cautiously accepted. When Keōua came ashore at Kawaihae Harbor north of Kona, Kamehameha’s warriors assassinated him and his men, sacrificing his corpse to Kū in a newly constructed and massive luakini-type heiau.26 Kamehameha forthwith possessed Keōua’s powerful mana and was deemed the outright Mō‘ī of the Island of Hawai‘i. Now middle-aged and with both Kiwala‘ō and Keōua dead, Kamehameha coveted additional islands under his personal chiefdom. We call the archipelago the Hawaiian Islands because that’s the Island of Kamehameha’s birth.

During his campaign, Kamehameha invited Nāmakehā, the powerful chief of Ka‘ū in the southern district of the Big Island, to join forces against Maui rival chief, Kalanikūpule and his armies on O‘ahu. Instead, Nāmakehā rebuffed Kamehameha and challenged his authority with power. Hostilities erupted between the two chiefs with the parents of ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia aligning their allegiance with Nāmakehā since his mother was a noble-born relation. Tragically, after Nāmakehā’s death in a fierce battle at Hilo, Kamehameha sought revenge by attacking the fallen chief’s settlements and unleashing his deadly forces against the family of ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia.

The name “Henry ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia” was completely unfamiliar when I received the phone call in the spring of 1993 from Henry L. Fuqua, whose Hartford funeral home had been contracted to remove Henry’s physical remains and prepare him for repatriation to the Big Island. As a well-established funeral director in the region, Fuqua had had a good deal of experience disinterring contemporary burials using mechanical excavators to lift metal caskets out of their vaults. But fragile, decomposing wooden coffins dating to the early 19th century were far beyond his experience.27 He needed a forensic archaeologist to conduct the sensitive exhumation and was advised to contact the state archaeologist for assistance.

Law in Connecticut is such that any time human skeletal remains are uncovered and determined by the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner to be older than fifty years and associated with an unmarked historic grave, the investigation is turned over to the state archaeologist for identification, removal if necessary, and reburial according to the cultural prescriptions of the deceased.28 Under this legislative mandate, we had investigated a number of accidental burial discoveries as well as cemetery vandalisms, including a sand and gravel mining operation that inadvertently exposed a colonial farming family’s burial ground, a house expansion project that yielded 17th century Native American graves, and a mausoleum that had been violated to obtain human skulls for satanic cult rituals. As state archaeologist, we had run the gamut from modern criminal investigations to the respectful and professional treatment of historical burials accidently uncovered during construction activities or marred by deliberate unlawful desecration. We worked closely with the state’s Native American Nations, historical societies, churches, descendant families, and other associations representing the dead to facilitate respectful reburial of human remains.29

The unique request to disinter Henry ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia posed the first instance where we had been called upon to remove an undisturbed burial for purposes of repatriation. On the phone, Henry Fuqua related the Lee family’s petition for the return of their ancestor; upon hearing the story, we were more than pleased to use our expertise to assist.

Pleased, but also struck by the intimidating responsibility of handling ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia’s skeletal remains, his iwi, which houses his spirit (‘uhane), his powerful mana. The archaeological treatment of the iwi required restraint, respect, and sanctity. We were cognizant that ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia’s ‘uhane would be near, and our commitment was to handle them reverentially.

The morning broke bright and windy although the seas were unusually calm in the late summer of 1796. The playful surf splashed gently over rocks, soaking the sand of Hilo harbor. Peace and serenity gave way when Kamehameha, believed to be in O‘ahu at the time, unexpectedly appeared amid his war canoes around Pepe‘ekeo Point from the north. Nāmakehā, a rival chief from the southern Ka’u district, had threatened Kamehameha’s hegemony and transferred his warriors and their families to the northeastern Hilo districts, invading Kamehameha’s territory. When the ali‘i nui heard of the threat, he quickly returned with his large peleleu fleet of battle-ready canoes which emerged in great numbers across the sun-swept waters.

Prepared to engage the enemy with all their strength, Nāmakehā’s warriors were hopelessly outnumbered by Kamehameha’s forces. The invading canoes were paddled by strong, young men bent forward, sweeping their powerful rowing strokes in unison, borne by the floodtide, moving the attackers at an amazing and deadly speed toward the beach near the mouth of the Waiākea River.30 The Battle of Kaipalaoa had begun.

The combatants were mostly comprised of commoners—fisherman and farmers whose duty was to support their ali‘i nui, though some were professional soldiers, trained from their youth in the art of warfare. Once the invaders were on the beach, the attack started with a massive missile bombardment composed of javelins, followed by pikers who formed in ranks moving as an advancing wall of sharp spears. Then hand-to-hand combat ensued featuring the deadly art of lua, which emphasized bone breaking, wrestling, and strangulation, sometimes followed by dismemberment. To defend themselves, common warriors lathered up their bodies with oil making it difficult for their enemy to grasp them. Chiefs wore feathered cloaks which served as battledresses more than garments of opulence, used for protection from stone missiles and to hurtle their enemy onto the ground to be finished off with a spear or dagger.31

The warring parties fought their bloody battle along the waterfront. Defenders and attackers punished each other. Nonetheless, Nāmakehā’s supporters were overpowered and horribly slaughtered by Kamehameha’s invaders. As one of the last rival chiefs to oppose Kamehameha’s rule, he was hunted down, killed, and sacrificed at the Pi‘ihonua Heiau.32 In their frenzy of revenge, the conquering forces turned on the villagers that supported Nāmakehā, continuing their reprisal on the families of the defenders. The alarm was sounded among the survivors; households fled.

When Keau, one of Nāmakehā’s warriors, recognized that his fellow-defenders were being overwhelmed and the battle lost, he withdrew from the beachfront, retreating toward the village to protect his young family. Gathering up his wife, Kamoho‘ula, their two sons, an infant and the adolescent ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia, the family fled into the mountains. Running desperately on top of and around molten flows of hardened black rock and dense vegetation, they quickly escaped inland and upland, seeking refuge from the carnage.

Finding a small lava tube cave in the higher elevations, they concealed themselves for many days until hunger and thirst sent them on a quest for water at a nearby stream. As they quenched their parched, dehydrated throats, a war party of the enemy surprised them, capturing Kamoho‘ula and the young boys while Keau, hoping the warriors would chase after him, was swift enough to escape.

To entice Keau from his nearby hiding place, the warriors began torturing their captives, knowing that the cries of his wife and children would bring the father/husband/warrior out of his concealment. And it did, though his initial efforts to free his family were unsuccessful, forcing Keau to flee a second time. The torture continued; with the cries of his family unbearable and their suffering intolerable, Keau made another futile attempt to rescue them, only this time to be captured.

Huddled together on the ground, Keau attempted to protect Kamoho‘ula by encompassing her with his arms and body, while a warrior’s leiomanō, a sharp-edged, shark-toothed sword, slashed away at them.33 ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia watched in horrid disbelief as the assailants cleaved unrelentingly at his parents until they were brutally dismembered; heads decapitated; arms and legs severed. Panic-stricken, in shock, the urge for survival took hold. As his parents’ blood splattered his body, ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia gathered his infant brother, slung him over his back, and fled. His freedom was short-lived. A warrior’s pāhoa, or two-edged spear, impaled his infant brother, killing the newborn and toppling ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia to the ground. He was the lone family survivor of the torture and brutal onslaught.

With the blood of his parents and brother soaking into his skin, the boy was wrestled and subdued to the ground by the warriors. Being young and posing no threat to the enemy, ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia was hauled away as a prisoner of war while the corpses of his mother, father, and brother lay behind, exposed on the ground for feral pigs to consume. Despondent, the abducted ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia was coerced into serving as the personal servant of the warrior who mutilated his parents, compelled to submit and live in the household of the murderer of his family.34

Big Island of Hawaii highlighting places associated with ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia.

‘Ōpūkaha‘ia was born in the shoreline village of Nīnole, in the District of Ka‘ū, near Punalu‘u along the southern coast of the Big Island of Hawai‘i, circa 1787–1792, though it may have been as early as 1785.35 ‘“Opū-kaha-‘ia” translates as “stomach cut open” and may suggest a caesarian delivery, a birthing technique that would have been unknown at that time and highly unlikely since his mother survived and had another child.36 Some have suggested that the name may have been bestowed in the tradition of inoa ho‘omana‘o to commemorate the event of a slain, dismembered royal person, maybe a chief during battle. However, ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia related a story to Thomas Hopu while they were sailing the Pacific Ocean onboard the Triumph: that he had received his name when a woman in his village died during childbirth. Her husband immediately cut open her stomach to save the infant and “ ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia” was chosen as his namesake in honor of the event.37

He was descended from a family of Hilo chiefs on his mother’s side, distant kin to Kamehameha.38 He was not a commoner, though not considered royalty; his pedigree derived from noble family lines in Maui and the Big Island.39 His childhood would have been as any traditional Hawaiian boy, predominately ‘ohana-centered, working together and sharing all aspects of social life from the physical land, food, and shelter to the spirit of Aloha. He would have had a far wider range of behavioral freedom than his restricted European/American counterparts since traditional Hawaiians raised their children in a far more relaxed and less constrained manner.

‘Ōpūkaha‘ia was nurtured by his parents and kūpuna (grandparents) residing in the same household. As he developed into boyhood, his grandfather carved a wooden bowl into which ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia would place a small stone as a form of confession if his behavior were not up to the family’s standard. He did this voluntarily when he knew he had disobeyed or was amiss in his actions. He did not have to be told. He would not lie or deceive his ‘ohana kinsman for they were his entire world.

‘Ōpūkaha‘ia’s education came from elders whom he venerated. He learned from his father how to fish, run swiftly among large lava boulders, dive, and swim strongly into the tide; his grandfather taught the cultural ways of Hawaiian traditions through storytelling, especially the family’s complex genealogy which defined their place in society. He developed into a resilient, intelligent boy with a sense of humor that was often entertaining, especially when he mimicked personal characteristics of family and village members. Great Aloha existed within this tightly bonded family, but dreadfully “Great Aloha” was broken by the warrior’s sword, which yielded death and captivity.

In preparation for ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia’s archaeological disinterment, I made arrangements to meet with Cornwall Cemetery sexton John O’Donnell to consider the logistics of the undertaking. John was a burly, muscular, no-nonsense caretaker who wanted this exhumation to be conducted properly. Meeting at the cemetery entrance, we drove to a prominent hill in the southeastern section where the earliest graves were located. I walked out ahead of John, ascending a relatively steep slope of manicured lawn, studying late 18th and early 19th century tombstones delineating long-standing, prominent Anglo-Saxon names in the community. A small, damaged tombstone, having toppled over and lying on the ground, caught my eye. It was dedicated to Thomas Hammatah Patoo, a native of the Marquesas Islands who studied at the Foreign Mission School and died in Cornwall five years after ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia.40 I continued my search for a similarly deteriorated vertical or horizontal headstone engraved with the name “Obookiah” but could find none. At last, John joined me and silently motioned to follow him further up the hill.

‘Ōpūkaha‘ia’s burial monument, Cornwall Center Cemetery, Cornwall, CT. (Courtesy of Bill Keegan).

As we ascended the steep slope, John was advancing straight toward a rectangular stone table. The platform, composed of granite boulders, some the size of basketballs, was positioned on the incline of the hill so that the top of the table at the upper (head) end toward the west was less than a foot off the ground, but almost two feet at the downslope eastern (foot) end, leveled to balance the precipitous embankment. Lying face-up on the table was a beautifully carved, white marble tombstone with shell beads, pineapple, coins, candy, and other trinkets placed on top. Though the stone’s engraving was darkened by years of acid rain, the epitaph was still legible. The sizeable lettering at the head of the stone read:

In Memory ofHENRY OBOOKIAHA Native ofOWHYEE

When I queried John concerning the beads, food, and money, he acknowledged that visiting Hawaiians often made pilgrimage to Cornwall specifically to pay their respects to ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia, their countryman who never came home. In tribute they frequently placed offerings on his memorial. I was dumbstruck. Expecting a timeworn vertical fieldstone marking the grave, I was unprepared to find a raised-stone pedestal usually reserved in historic New England cemeteries for the most elite members of the community, mainly ministers, and totally unheard of for a man of color. I certainly did not anticipate a place of pilgrimage, a shrine.

‘Ōpūkaha‘ia, now a prisoner of war, was compelled to serve and reside with the warrior who murdered his parents and brother.41 He was taken to his captor’s home at Kohala,42 birthplace of Kamehameha and the northern point of the Island of Hawai‘i, the geographic opposite from ‘Opukaha‘ia’s home village at the southern extent. At the onset of his altered life, he suffered the constant anguish of survivor’s guilt. If only the pāhoa that impaled his infant brother had penetrated deeper, he would have died with them. What had he done wrong? Should he have stayed and fought to the death over the bodies of Keau and Kamoho‘ula? Would his brother be alive if he had not fled? Was he a coward? His remaining years on Hawai‘i, and even later in New England, would be characterized by a tormented mind, subsumed in the abyss of the dark hours, sustaining periods of self-remorse and despondency, searching to find answers to questions that gave no answers, no resolution.43

The wife of his captor treated him kindly and even the man that killed his parents did not abuse or overwork him. Nonetheless, the face of the warrior that had tortured him and violently executed his family was a constant reminder of the horror he withstood. ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia existed solely with feelings of profound culpability. He suffered many nights where he cried himself to sleep while living with his captors for almost two years.44

In time—and quite unexpectedly—‘Ōpūkaha‘ia reunited with his mother’s brother. This uncle, Pahua, was the praying priest (kahuna pule) at the Heiau Hikiau in Nāpo‘opo‘o and had arrived in Kohala while traveling around the island to collect tribute to cover the costs of the Makahiki festivals.45 At these times, chiefs would confine people to their huts by virtue of kapu, while the kahunas, bearing the figure of the god Lono, would liberate them through the collection of tributes (i.e., pigs, dogs, tapa, etc.) paid to the ali‘i in support of the Makahiki, which was initiated in honor of Lono’s wife, Kaikilani.46 Pahua had trained under the tutorage of Hewakewa, the high priest (kahuna nui) of Kamehameha, and may well have been present at Kealakekua Bay when Capt. Cook was slain.47

At first, Pahua did not recognize his nephew. The last time he had laid eyes on the boy ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia was a mere child, and he had now grown into a young teenager. Uncertain, Pahua inquired about his parents and when he heard the name of his sister, Kamoho‘ula, the priest broke down in tears. He had thought ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia dead. Trembling, Pahua could hardly believe his fortune. His nephew was alive, saved by the gods and reunited with him.

The kahuna resolved that the boy should not return to the home of his captive, insisting that he must dwell with him and his maternal grandmother, Hina, in Nāpo‘opo‘o. Reconciled with his true family, Pahua planned to take ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia under his wing, tutoring the boy to follow in his footsteps and enter the priesthood, devoting his life to the gods who had saved him. Determined, Pahua instructed the young boy to return to his captor and petition for his release.48

The warrior who retained ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia did not take the request calmly. Angered at the thought of releasing the boy, the countenance and menacing voice of the man put renewed fear into ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia, who would never be allowed to leave until his slaver died, or the boy died first, which the warrior threatened. ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia wanted so desperately to go with his uncle—to be rid of the face that reminded him continually of his parents’ merciless deaths. Yet he was powerless. The confrontation reopened deep emotional wounds.

After his encounter with the warrior, ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia sought out his uncle and told him of his captor’s ire at the mere idea of yielding his freedom. Pahua fashioned an attitude, instructing ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia not to return to this vile man, but remain by his side. Let the warrior, his sister’s murderer, come to discuss this with the priest. Pahua would handle the situation personally; as a kahuna, he had the power and influence to do so.

A few days later, the warrior approached Pahua to collect his property. Pahua spoke eloquently of ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia as his own child, making it clear that he would not let the boy leave him under any circumstance. If the warrior insisted, he must take both ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia and Pahua back with him as captives because the priest would never let the youth leave his house alone.49

In the end, there would be no confrontation, no frightening outcry. Pahua was a man who served the gods. His mana was far more powerful than that of the abductor. Whether out of respect or fear of the kahuna, who was capable of praying someone to death,50 the warrior acquiesced and agreed to give ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia his freedom. He gave the uncle one curious stipulation: “You must treat him well and take care of him in a proper way, just as I have done.” Pahua agreed that it would be satisfied.51 Had this enslaver of ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia, murderer of his family, become fond of the boy? Or had he accepted that he was in no position to challenge the kahuna and, thus, attempted to make a good appearance of his predicament? Whatever his motives, ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia was now free to live with his uncle and train to be a kahuna, maybe even take his place as the praying priest at the Heiau Hikiau.

Under Pahua’s mentorship, ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia matured into a bright and resourceful young man. Beginning his apprenticeship as a kahuna, Pahua trained him hard, demanding long tedious hours commencing at sunrise and continuing throughout the day, well into the late night. ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia strained to learn and memorize long litanies; repeating them daily at the heiau, ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia prayed for the life and happiness of the chiefs, for their safeguard from enemies, for beneficial weather and productive crops, for protection and appeasement of the akuas to prevent volcanic eruptions, tsunamis, and earthquakes. He was intelligent and quickly learned the extensive prayers and associated rituals to uphold kapu and to forgive violators. He committed to memory thousands of verses that were part of the significant oral histories of the Hawaiians, including Kumulipo, the Hawai‘i creation chants. Though the long hours and intense study commanded his attention and brought on exhaustion, during the evening, thoughts of his family’s deaths still haunted him into the night until welcomed sleep approached. Beginning a new life under Pahua’s protection and Hina’s guidance, ‘Opūkaha‘ia was being groomed to be a person of great magnitude among his people. Nonetheless, his soul remained anguished.

His seminary was the Heiau Hikiau in Nāpo‘opo‘o, by now an international deep-water seaport. Hikiau is translated as “moving current” which graphically describes the heiau’s location along the lower edge of an ancient surfing beach at the inner, easternmost recess of Kealakekua Bay. Heiaus were special places of reverence. All Hawaiians lived to honor the gods and frequently had a small heiau, usually an altar or shrine in which to worship daily, within their houses. Formalized, larger heiaus, where ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia studied and institutionalized priests held ceremonies while praying for the needs of the chiefs and their people, consisted of wooden-fenced enclosures upon large stone platforms containing several houses, including massive open-air temples on top of the extensive stone podiums. Multiple carved wooden idols, akua ki‘i who stood upright sporting grimaced faces, required appeasement. Only the chiefs, nobles, and priesthood could enter these large stone platform heiaus of the luakini-style, designated for human sacrifice. Maka‘āinana were restricted by fear of death.52

The dichotomies of peace and war as well as conformity and conflict were a part of ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia’s preparation. He became knowledgeable in the manner to pray, serve at rituals, and carve wood to symbolize religious icons. His entire existence was encompassed into a pantheon of akuas, spirits and other supernatural beings residing in the woods, amid volcanic boulders, in the ocean and onshore, entering into all animate and inanimate objects. There was no distinction between the natural and supernatural worlds. They were one and the same. ‘Opūkaha‘ia was trained to become the vehicle for maintaining the proper relations between these spirits and the people, the mediator between the gods and the Kanakas Maoli, maybe even becoming a kahuna nui at Hikiau, and presiding over all aspects of their Native religion behind the sacred wooden enclosures.

Adjacent to his seminary and along the shore, ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia constructed a small, personal heiau he named, Helehelekalani. Within, he built three small shrines to Lono, Kū, and Laka, the god of the hula.53 Pahua was proud of his nephew, but he may have worried that being away from the secured enclosure on top of the heiau would bring ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia in closer proximity to the seafaring haole (foreigners), with their irreverent behaviors and disregard for kapu, posing a threat to all existence.

For more than twenty years, my right hand man on archaeological field expeditions was David G. Cooke from Rocky Hill, Connecticut. Although an amateur, Dave had a passion for history and archaeology that could not have been surpassed by any academically trained anthropologist. A retired machinist by trade, Dave was meticulous in recording data, and he remains simply the best field technician I ever worked alongside. He would be with me for the disinterment of ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia and was especially valuable in the systematic removal of the stone monument weighing above the burial and in organizing the volunteer field crew.

In the late spring of 1993, Dave, along with volunteers, Richard (Dick) LaRose and Gary Hottin, both avocational archaeologists, and William (Bill) Keegan, an undergraduate student of mine from the University of Connecticut, were assisting in the mitigation of sites associated with the 19th century Enfield Shaker’s farming community. Lego, manufacturer of the popular plastic building blocks, was planning expansion of its offices and warehouse immediately adjacent to the Shaker South Family Farm; as state archaeologist I had raised concerns for the necessity of an archaeological survey to ensure that construction activities would have no adverse effect on any significant cultural resources associated with this National Register of Historic Places property.54 The five of us where in the field salvaging a mid-19th century Shaker refuse deposit when I casually mentioned the ‘“Opūkaha‘ia Project.”

Dave consulted with a friend who serendipitously had purchased an 1819 first edition of Edwin Dwight’s “Memoirs of Henry Obookiah” at an antique bookstore days before. Passed from hand-to-hand, the narrative would inspire all of us with the true significance of ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia’s life and death, furnishing a much better understanding of the roles we were about to assume.

Our excavation plan provided for a systematic removal of stone and soil deep enough to expose whatever remains of Henry ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia were still preserved in the ground. The excavation unit was limited to a narrow forty-six inches wide by ninety-six inches long rectangle directly underneath the stone table so as to avoid the possibility of encountering other human remains, which may reside in adjacent unmarked burial plots. We anticipated evidence of soil disturbance from the original digging and refilling of the grave shaft and of encountering ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia anywhere between four and six feet below surface.55 Considering the Cornwall Cemetery Association’s concerns that even with the stone table in place the exact location of Henry’s remains was unknown, we were prepared to record biological characteristics of the skeleton in situ to determine whether the remains were that of ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia prior to repatriation. To assist in the osteological analysis, we invited Dr. Michael Park, physical anthropology professor at Central Connecticut State University and my first instructor in the forensic aspects of the human skeleton, to participate in the field, expediting identification and later to serve in the laboratory, providing a more thorough analysis.

With the field team assembled, we selected July 12, 1993, to commence the exhumation of Henry ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia. Dave Cooke would oversee the archaeological operation; Bill Keegan would be the project photographer; Dick LaRose and Gary Hottin would assist in screening soils, recording of data, and other excavation logistics; Mike Park would be prepared to examine any skeletal remains recovered, and Will Trowbridge, a local stone mason, would assist in the removal of the raised granite table and be responsible for its restoration after the disinterment was complete. Also joining us was the Rev. Carmen Wooster, United Church of Christ, who represented the Lee family, David A. Poirier, staff archaeologist at the State Historic Preservation Office, and Jeffrey Bendremer and Shelley Smith, graduate students in the Department of Anthropology at UConn. All equipment and personnel were on site early that July morning, which was forecast to be hot and humid with the possibility of thundershowers in the afternoon.

It was probably through his uncle that ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia would learn of an aunt, the sole surviving sister of his father, living nearby. Granted a break from his studies at the heiau, he travelled to her village, renewing their relationship. Regrettably, his aunt had angered a local chief by committing an infraction of the kapu, so when the chief sent his warriors to apprehend her, they discovered ‘Opūkaha‘ia. Both were seized and incarcerated in a guarded hut while the chief decided what to do with them. Overhearing the conversation of two sentries that he and his aunt were to be put to death, ‘Opūkaha‘ia made his escape by crawling through a small hole, absconding out the opposite side of the patrolled entrance. Unobserved, he fled into the thick, tropical vegetation and hid. Horrified, ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia watched from his concealment as the warriors dragged his aunt out of the hut and brought her to an elevated precipice. In executing orders from the chief, they flung her over a steep pali (cliff), crashing to her death hundreds of feet below.56

Once again ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia was caught up in the rivalry of competing chiefs; once again he witnessed the violent death of a family member; once again he survived and felt responsible; once again he despaired. Mental pictures of his parents’ brutal murder and his brother’s impalement came rushing back to him with his aunt’s execution. Anger and guilt revisited. Surely he had caused the death of his aunt by escaping from the hut, just as he had his brother’s when they fled from their parents’ execution. What was the point of this unremitting life, filled with the death of loved ones that he, in his cowardly behavior, had caused? He could obtain no answers, elicit no sympathy, find no wooden bowl into which to place a stone to confess and seek forgiveness for his actions. Despair and self-recrimination assaulted his brain.

Confused, his mind raced and his body propelled him, the same as his flight from the sight of his parents’ dismemberment. ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia broke from his concealment, rushing toward the same precipice from which his aunt had been hurled, hoping to replicate her death and follow her into eternity over the same pali, the same cliff. Death would be a welcomed relief.

Two of the chief’s men saw ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia’s charge and took chase, catching up to him before he could hurl himself off the mountain. They tackled and subdued him. He cried out to be released but was held down by the strength of the warriors and the intense weight of his suffering. After overpowering him and foiling his suicide attempt, the warriors transported their captive to the chief’s quarters.57

Learning of ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia’s identity and his kahuna training, the chief who ordered his aunt executed returned his sullen captive to Pahua so the young man could resume his priestly studies under the benevolent care of his uncle. Though free and back home, ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia remained reclusive and contemplative, developing an inner desire that he kept to himself—a yearning to leave the islands and break the cycle of violence, to start anew and journey to some distance place—to forget.

‘Ōpūkaha‘ia wrote many years later that it was at this time in his life that he began to consider leaving Hawai‘i. “Probably I may find some comfort, more than to live there without a father or mother. I thought it better for me to go than stay.”58 He had formulated no specific plan for his exodus until serendipitously he spied the Triumph, an American merchant ship out of New Haven, Connecticut, sailing into Kealakekua Bay in 1808. The Triumph, a rather slow, but sturdy two-mast brig, constructed of strong Connecticut oak,59 dropped anchor in the bay and began loading water, food, and wood supplies, while ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia mulled over the idea of leaving the island onboard this American ship.

Should he forget this notion of abandoning his uncle and his priestly studies? If he left, where would this journey take him? Would he truly forget his personal horrors? While his mind pondered these mostly negative thoughts, he made his decision. He would go; better to do so before he was complicit in the deaths of his beloved uncle and grandmother as he had been for his brother and aunt.

Impulsively, he dove headfirst into the surfing waters, sturdily swimming against the tide toward the twin-mast sailing ship. Though he was a strong diver, his heart pounded at the thought of his impulsive plan coming closer to reality with every stroke he swam. Beside the anchored ship, he reached for the rope ladder and hoisted himself upward onto the deck. Summoning the courage to act, ‘Opūkaha‘ia looked around at the strange wind-burned European faces. He observed a Hawaiian interpreter conversing with the ship’s captain. Approaching them, ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia asked to have his words translated and immediately petitioned Capt. Caleb Brintnall to take him on as a member of the crew.

Sailing out of New Haven just prior to the enforcement of the Embargo Act of 1807, the Triumph was part of the China Trade commerce of the early American Republic. The potential profits from the trading of seal furs for Chinese wares and spices were staggering for its New England investors, and worth the dangers and uncertainties of a voyage that could last two to three years. Under the watchful eye of the resourceful Capt. Brintnall, who ran a tight ship, confident investors found the risk worth taking, especially in exchange for the immense fortunes to be earned in New York City financial markets.

The Triumph carried twenty guns, including four and six-pound cannons for protection against Spanish vessels blockading foreign ships intent on poaching seals off Baja waters. Entering the Pacific Ocean via the tumultuous currents around Cape Horn, the Triumph proceeded northward toward islands off the South American and Mexican coast that offered rookeries where congregating seals could be easily procured. Leaving a small crew behind to manage the dirty work of killing, skinning, and processing fur on islands off Baja California, Brintnall headed west to Hawai‘i to replenish the ship’s provisions.60

Arriving first in Honolulu, Capt. Brintnall received permission from Kamehameha to trade and take on Hawaiian males as additional crew for their return trip to the Baja sealers. Now anchored in Kealakekua Bay, Brintnall looked over the young teenage ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia and felt he would fit the bill, possibly making a good seaman as Polynesians were known to be. Nevertheless, Brintnall was also cautious, wanting no trouble with the Hawaiians. Permission would have to be granted from the boy’s family. When told by the interpreter that the boy’s parents were dead and he was the nephew of an important kahuna, Brintnall invited ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia to have dinner and spend the night onboard ship but would make no abrupt decision.

Onboard the Triumph was another young Hawaiian named Nauhopo‘ouah Ho‘opo‘o (Hopu), called Thomas by the American sailors. Born in 1795, Hopu was nine years old when his mother died. His father taught him the traditional ways of Hawaiian culture, but also instilled in the young boy that today’s magic comes from the haole and all their iron, nails, knives, and guns. Always keep Hawaiian ways in your heart, Hopu would be taught, but acquire the new practices, for tomorrow’s success and continued existence will come by knowing the customs of the light-skinned haoles. Accordingly, when the Triumph arrived, Hopu’s father gave permission for his son to go aboard and travel with Brintnall; he could be educated and learn the secrets of their valuable technology.61

Brintnall kept his eye on ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia throughout supper. He noticed how the young “heathen” seemed to pick up Western gestures and comportment of consuming food at the officer’s table. Though ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia could little understand what was being spoken among the officers, his gift of mimicry allowed him to follow their behaviors and copy their table mannerisms. In his handling of a fork and knife, ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia was deemed a quick learner. Brintnall asked the young Native if he would like to go to America, become a luina kelemania e, a sailor, on their ship. Once he understood, ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia replied with a positive nod of his head and was overjoyed.

After spending the night onboard the Triumph, ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia was informed that he would need his uncle’s permission before he could accompany the crew on their voyage. So the young Hawaiian returned to shore seeking Pahua’s acquiescence to leave the island. When they met, his uncle questioned ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia as to his overnight whereabouts. His nephew told the kahuna pule that he had spent the evening onboard the ship, and furthermore, Capt. Brintnall had invited him to join the crew and sail with them; he very much wished to do so.

Pahua flew into a rage. How ungrateful was this child after the gods had twice spared his life? He and his grandmother had been sick with worry when ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia did not return in the evening, and now he wanted to leave his family entirely, leave the island, leave the heiau and leave his studies? No, he was saved to serve the akuas and that was exactly what he would do! Angrily, Pahua forced ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia into his hut, shutting him in.

Hina implored her grandson to give up this foolish idea of leaving Hawai‘i. They loved him and were frightened that if he did leave, he would never live to return. ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia assured her that he likewise loved them, but he needed liberation. There was an aching in his heart. He had wanted to move on for a long time and this was his opportunity. He must travel on this journey, he insisted. Maybe he didn’t truly comprehend all the reasons why he had to go, but he simply did. He assured her that he would return in a matter of months. She left the hut with tears in her eyes, knowing he would never come back. He was a very foolish boy.62

Pahua would hear none of this pleading. There would be no discussion of deserting the island, his family, or his training. ‘Opūkaha‘ia would be confined to the house, a captive once again, until the Triumph left the harbor. The repeated injustices welled within him. He was incessant, more determined than ever. Defiantly, he would become a luina kelemania e and find the new life he was searching for among the American haole. Nothing would stop him.

While inspecting his latest prison, he noticed a weak spot in the back of the grass hut and crawled through it as he had when confined with his aunt. Unnoticed, he worked his way downhill to the waterfront, hiding until darkness, then silently waded into Kealakekua Bay, swimming out once again to the anchored Triumph. This time he climbed aboard secretly, careful not to be seen by the sailors, and concealed himself below deck among the cargo crates. With luck they would not find him until the ship was well underway, a stowaway. But his plan was foiled when he was discovered the next morning about the time Pahua’s canoe appeared alongside the large sailing vessel.

With the inherent dignity of a proud and influential kahuna, Pahua came onboard the Triumph, declaring to Brintnall that ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia had run away, was hiding on the ship, and must be found. The captain, impressed with the presence of the kahuna, ordered a search for ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia, who was readily brought forth. Straightening himself and fighting back tears, the young man pleaded again for his release to follow the Americans, to go on his journey, appealing to his uncle that a force in his soul cried out for him to leave. He must go, and he would go.

Resigned, Pahua realized that one way or the other ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia was going to abandon the island, either on the Triumph or another sailing vessel. Pahua respected Capt. Brintnall, whom he knew to be honest and trustworthy. If ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia must go, this was the haole that would surely care for him. Nonetheless, the gods would be angry and must be appeased. Pahua would grant ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia his request, but first Brintnall must purchase a pig to be sacrificed to ensure the boy’s protection and consent of the deities. Their parting was disagreeable, but ‘Opūkaha‘ia was willing to “leave all my relations, friends and acquaintances; (and) expected to see them no more in this world.”63