Читать книгу The Paradise Stain - Nick Glade-Wright - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Seven

ОглавлениеKiwi Janine, who was wearing a smart shirt with jacket and slacks, knocked and entered Kant’s office. Kant looked up from a share prospectus Maxwell had advised him to study. Phew, Dorothy’s had a word in her ear, Kant thought as she ushered John Sturges in.

‘Here’s Muster Sturges, Muster Kant.’

‘Ah, welcome John. Please sit down. Can I offer you a coffee?’ Kant said, standing up and shaking his hand.

‘I’m pretty right, thanks. The lass ’ere just made us one.’

Janine lingered at the door. Kant suspected the girl had aspirations to be more involved with the proceedings at the station. Television stations often brought out romantic notions of fame with some of the younger employees.

Kant nodded at her. ‘Thanks, Janine.’

She swivelled and disappeared.

‘Nice lass,’ John Sturges said warmly.

‘Yes, very pleasant.’

‘Told me she come from Christchurch. Real bad about that earthquake.’

‘Yes, it was terrible. Please John, have a seat.’

Kant sat in the other armchair, crossed his legs and leaned a little towards his guest, who had perched himself near to falling on the edge of the chair holding his knees.

‘So. Vince has had a preliminary chat with you at home.’

‘Well yes, he did. He come round, brought some little cakes too. Nice fella.’

Kant smiled. ‘That’s why we employ him. And I have to say, John, he must have really liked you.’

‘Oh? How’s that?’

‘Well he’s never brought me any cake before.’

John grinned with pride. ‘Sorry about that.’

‘It’s okay really. Now … ’

‘I don’t know what ’e told you but it’s hard to just remember everything off the top of me ’ead. Dunno why I agreed really. But he made me feel kinda easy, you know, to tell stuff.’

‘Sure. All right, well how about you start at the beginning, and if we decide that your story is suitable then we’ll go through how the interview will be carried out on air so there are no surprises for you. The program is not live so we always have plenty of time in which to edit things that don’t work well for you, or indeed us. Think of this as just a chat between two mates … in a pub, very relaxed. How does that sound?’

‘Righteo then, sounds fine.’

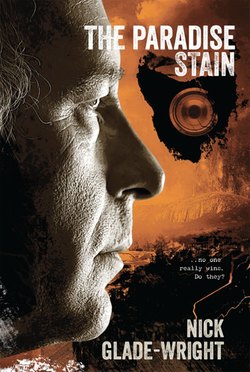

John Sturges looked about seventy years of age but he had told Vince he was sixty four. It had not been a compassionate life that had embraced him. The gritty lines, parallel furrows in arid soil, had long been ploughed across his forehead, signs of life’s brutal grip. His wiry unkempt grey hair was in need of basic grooming and his clothes were op shop specials. But it wasn’t so much his appearance that gave the man a washed up look but the way he carried himself. This was not an assertive man with straight back, looking assuredly into a bright future, no. This man’s whole demeanour was weighted down as if merely keeping his body together, his arms, his shoulders, his head, was an effort.

But to get on the show there would have to be more than just feeling sorry for yet another down trodden old fella fallen on hard times.

‘I told the other bloke about how I was treated real bad when I were in State care. Like, you know, Wyborough Hall up Mangalore, ’n’ Ashley Boys’ Home, ’n’ that.’

‘Ashley Boys’ Home?’

‘Yeah. I also spent some time earlier with the Salvos too. That was real bad too. Then when I was at Brighton Area School this kid died of a brain tumour; they reckoned it were me what killed him. I’s called murderer ’n’ stuff. The psychiatrist, he said there was nothin’ wrong with me. The kids and even summa the teachers said I bashed ’is ’ead on the concrete. I never did. Even in Ashley they bashed the guts outa ya.’

‘The boys’ home?’

‘That’s right.’

Kant was already losing the continuity of the man’s nervous ramble. Things that had happened to John Sturges forty or fifty years ago had fused together into a cluttered medley.

‘John, you mentioned the Salvation Army. Surely they would have provided a safe haven for you?’

‘You’d think so, wouldn’t you? There was Major Finlay and Captain Sullivan; keep y’in a dark empty room with nothin’ to keep warm, no bed all night.’

‘How old were you when this was happening?’

‘Five, thereabouts.’

‘Five!’ Kant repeated. ‘Surely you could have told someone. What were your parents doing then?’

‘Dunno. They sent me there ’cos I were a tearaway really; runnin’ away, stealin’ stuff.’ John smiled at this description of himself. ‘I were a bit of an ’anful, see. They just took off, I s’pose. I think someone said they went to Queensland, or me father did anyway. I dunno.’

Although John had clearly endured a hard time growing up in the fifties in Tasmania, there were lots of other people who did it tough. Social support networks were not so much in place then, and so many were left to their own devices, to either sink or swim. There would have to be more to John’s story for him to be a viable contestant.

‘Your dad, what was he like?’

‘Dunno really. Used to bash ya when ’e was drunk. Never touched me sister though. I s’pose I couldn’t fight back being a bit younger ’n’ that. Back then, as I said, I was a bit of an ’anful, you see, a bit wilful like.’ Again, the sheepish grin.

‘So how old were you back then? When your father … hit you, John?’

‘Two.’

‘Two!’

‘I think so. Oh, maybe two ’n’ a ’alf,’ he added, as if the extra six months made a difference. To Kant it sounded like an apology for being such a handful, excusing his father’s violence because that was all he had possibly ever known.

‘Jesus,’ Kant whispered. He hadn’t meant to lose his compo sure but all he could think of was Rosie, proud to be two and a half, steeped in so much love and nurture.

‘See, I reckon it was me being a tearaway. That’s why they sent me to the Salvos. Later, after I left the Brighton school I was sent to Ashley in Deloraine. I was twelve by then but they still kept it on the books like. You know, me being a murderer an all.’

‘You mean the misguided suspicion that you had hurt the boy?’

‘I dunno. I think they always thought it were me, like they wanted someone to blame for stuff. Summa them guards, like I don’t reckon they were very happy themselves.’

‘Yes, I can certainly understand that.’

John scratched at the stubble on his chin. ‘Them kids there, and even the staff, still used to bash ya. I run away, I did. Just took off. They told me eventually that it wasn’t me. Not for a coupla years though. Like, you begin to wonder whether you really did do it. I stole a few things, nothin’ real big, when I took off to the city, you know … like a bicycle off of a verandah to get round and stuff.’

‘How do you feel about that part of your life now, John? It was a long time ago.’

‘Yeah I know but … ’

Kant waited. He suspected there was more to the story. There must be. How could anyone remember such details after half a century? Just then a text came through on Kant’s iPhone. Ignoring it, he looked at John with a reassuring smile.

‘It’s hard, isn’t it? So much from our past can get lost, or hidden,’ Kant said, not realising how prophetic his statement would become.

‘It’s not that; it’s hard ’cos some things just don’t go away and … ’ John heaved a sigh.

‘It’s okay, mate, your story’s safe with me. And if you don’t want to go ahead, everything you’ve told me will remain completely confidential.’

John looked around the walls at the artworks, his eyes remaining for several seconds on each piece before moving to the next.

‘You have some nice things ’ere, Mr Kant.’

‘Thanks, but call me Barry, please. I collected them all over a lifetime really. They’re like a chart of my travels with my wife.’

‘I like that.’

John breathed in and filled his lungs. He allowed the air to smooth out a clench that seemed to have constricted his chest. ‘See … like … like there was this other time … I spent in Dominic; you know, the Catholic school.’

‘Here in Hobart?’

‘Yeah. I spent some time there, only a few months. Me older sister Elsie, who lived down Primrose Sands, said it would be a good safe place to go and … like … get better, be cared for, but … ’

A fearful realisation began to churn in the pit of Kant’s stomach. Oh God, here it comes, I should have guessed.

After a few minutes Kant wound up the interview and booked John Sturges into the show. He had to remind himself this was not a counselling session as he watched the old man trudge heavily from the room. His was a big story, even for BKS, and Kant, already feeling the enormity of the responsibility, needed time to assimilate the dreadful nature of a crime that had been perpetrated on this gentle old man so many years ago and was still poisoning him like a rusty spike driven deep into his soul.

Already, Kant’s first day back had given him more than he was ready for, so he postponed the afternoon interview with the African lad for a later date, to be confirmed, and fixed a strong coffee for himself. While the coffee machine was doing its thing he opened up the message on his iPhone. It read: your fulla shit fagot.

Kant stared at the message for several seconds. It was his turn to sigh. ‘Is that a fact?’ he said, pressing the delete button. Boiling brown liquid began to splutter into his cup.

*

At the top of the wooden stairs, rising directly from the street to the first floor landing, Mungo flicked a light switch that activated several low wattage globes in the dim passageway and in the largest room to the left, which had become the main studio. There was no light switch in the room. Random, dodgy modifications over the years had presented such anomalies to the workings of this character space but suited the nature of their experimental work. The three men had all made various forays into the Art School as well as completing degrees at the Conservatorium of Music. A solid grounding in formal techniques was essential before the true creativity of bending all the rules could take place.

Below on the street frontage was a Moroccan rug shop next to a milk bar. To the lads, Moroccan food in a Kasbah would have been preferable.

Elizabeth Street was the main artery connecting the city’s heart, several blocks down the road, with the fashionable North Hobart nucleus of cosmopolitan activity a few blocks up, with its restaurants and trendy cafés, wine sales, pubs, alternative cinema, art galleries and music venues. Not with a Lygon Street sort of Melbourne ethnicity or with a Kings Cross Sydney exuberance, but in a ‘ there’s no one around after ten in Hobart’ sort of graveyard way, as Sammy, the band’s twenty four year old percussionist often complained about it.

At night, Hobart’s CBD, several blocks down the street, was a desolate and windy place where the homeless hunkered down and the crime intent scuttled around ‘ like underfed crocodiles in a caravan park’, another of Sammy’s little lyrical triumphs, particularly when he was on the weed.

The band, Global Synthesis Trio, a purposely pretentious mouthful, (and sick of the tax the genuinely penniless still had to cough up), had set up the studio with the banks of second hand keyboards in two rows facing each other, giving easy access to all the wires, cables and connections in the middle. To one side the drum kit and associated percussion instruments had been set up on a higher plinth, giving Paul elevation to see Sammy and Mungo at their respective keyboards.

Paul Leonard, solid build, head insulated with black curly hair had been brought up in Cairo in his early years. He was often mistaken for being Greek but his parents, archeologists, were actually English. Much of their research was based on hieroglyphics, deciphering the secrets of the past. Paul had met Lena, a Tasmanian who had been visiting the pyramids. Not long after their meeting under the Sphinx she had tempted him with her beauty and the lifestyle of Hobart. To his parents’ disappointment, Paul flew back to Australia with Lena, but they went their own ways a year later. Paul’s brief emotional vacuum became occupied again after teaming up with Mungo and Sammy, drinking buddies only at first until they all realised they shared the same passion for eccentric music.

Whenever another musician ventured into the space a jam session would ensue, injecting a different sound into their music, twisting it even further. Electronic sampling was an important aspect to the finished product, as Mungo explained to Melinda when they first started. ‘You start with something that is basic, unadulterated like a baby at the beginning of life. You take its pure nature and manipulate it through recording it and redesigning it electronically, the denaturing of innocence. In our case we end up with a multi facetted soundscape. An amalgam, representative of all the urban sounds we take for granted and have stopped hearing, but are at the very core of our lives,’ Mungo continued earnestly.

‘I love it when you talk dirty,’ she’d replied.

Littered around the remaining spaces were extraneous objects, junk retrieved from a disused machine factory that tantalised their uninhibited musical impulses, to strike, shake or rotate. PVC plumbing pipes of various dimensions hung from the rafters; the longer they were the lower the note that emanated from them when hit with a rubber thong. Two dismembered piano frames were suspended too, to be plucked, hammered or ruffled. As well, there were sheets of steel, hub caps, even an old vacuum cleaner with the pipe connected to the outflow opening and the other end inserted into a large plastic drum filled with table tennis balls. It was within the process of unconstrained play where the magic was found, recorded then merged with conventional percussion beats and scale structures.

Sammy arrived eating a cold slab of what looked like two layers of last night’s pizza. Paul, the same age as Sammy, breezed in seconds behind, coke in hand, grin on face. The smug expression, cultivated to a fine degree, needed no explanation. Apart from being a reliably accurate barometer for some recent carnal interaction with the opposite sex, he was hopeful it conveyed an alpha male image, suiting his reputation for being unattached and therefore, in his mind, irresistible to all women.

Mungo, who was several years older than the others, had taken on the role of Godfather in the band, ostensibly because he had a kid and lived with a regular partner. This seemed to allow him the unique status of responsible adult which the others were not yet ready to accept for themselves. Sammy and Paul liked to play the single, we have lustful sex every night you poor married bastard game with Mungo, who played along with it because he knew it patently wasn’t true. The lads spent most days and evenings playing music until their bodies were so tired they couldn’t raise the flag even if they’d wanted to.

Mungo looked up. ‘Morning.’

The others replied in unison, ‘Morning.’

Mungo, who had already activated his Korg effects system, microphone hanging in the middle of the room, record button red, played the greeting back to them: Morning … morning …

Then on a loop: Morning … morning … morning … morning … morning …

He sped it up to about twice the speed, inserted a chorus effect, then added an octave below. Paul picked up his drum sticks and began to play along. Kick bass in time with the words, high hat on the offbeat, sticks playing counter beats with the snare and toms and cowbell. Sammy shoved the last two mouthfuls of pizza into his mouth and began hitting two large metal pipes with a lump of wood, the doleful ecclesiastical tones befitting an elegy in some country churchyard.

Mungo adjusted the key to suit the pipes and began improvising a melody with his other keyboard, on top of what was happening. They seemed to play as if their lives depended on it, for a while not even looking at each other, simply imbibing the sounds, the rhythm, feeling and reacting to each other. After about ten minutes they began to give each other know ing glances, their actions getting more radical and the melodies more complex. It was the point where the synthesis of the sounds found a groove, fusing as one. They were all append ages of the same musical body, their minds tuned into hearing and predicting the others’ moves.

Mungo suddenly flicked his keys off, Paul ceased drumming and Sammy burst into laughter.

‘John Cage, eat your heart out!’

And so the young musical revolutionaries’ day had begun.