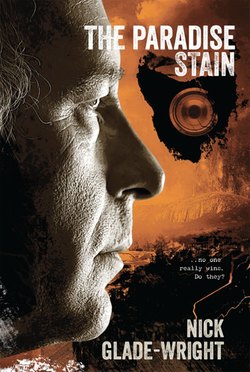

Читать книгу The Paradise Stain - Nick Glade-Wright - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Two

ОглавлениеIn the weeks following Sarah’s death two things induced Kant’s decision to move away from the sanctuary of his home in the country.

Melinda had never before witnessed her father weep, so at the sight and sound of him distraught and defenseless, and grieving her own mother’s death to the Cruel C, as she called the disease, she ached with sorrow.

‘Please come up town, Dad, so we can all be near each other.’ And knowing her father’s softness for his granddaughter, ‘You know how much Rosie loves her grandpa.’

He did. He felt supremely grateful. Amongst the rips of his emotions, barely keeping his head above water, this little girl, without an inkling of her influence, had buoyed her grandfather up in the bleakest of storms.

The second thing happened a week later.

Vashna and Barry’s other longtime friend Maxwell Dartford drove down from the city to stay the night at the cottage. A boys’ night’s what the maudlin old bugger needs, they’d plotted. Get him out of himself and back on track, they had decided before they phoned, refused to hear any excuses, turning up an hour later with a couple of Johnny Walkers.

‘Jesus, Barry, you’ve got more dirty dishes lying around than a Bangkok brothel,’ Max had started as soon as he entered the kitchen where the warm and welcoming aromas of home cooking had been replaced by a rancid and stifled coldness.

Max was a rare breed of human being, knowing nothing of emotional pain in his untroubled existence as capitalist, inheriting a bulging portfolio of investments, giving him the means to live more than comfortably, almost without having to lift a single digit. Financial advisers, brokers and a creative accountant took care of everything. All he had to do was find appealing ways to spend the profits while fostering his small city mystique and flashy front, which had the side effect of giving Barry’s life of solid plodding some pizzazz, like confetti sprinkled over a grazing bull’s back.

To give old Max his due, he did help propel the ailing economy when he became an art buyer, an activity that granted him specious social credibility. Healthy rumours that he was bound to be into some kind of unethical practice, and a brief scandal about an exploratory gay liaison, were to his manicured persona like healthy dividends at the end of the financial year.

‘Sensitive as ever, Maxi,’ Vashna had said. ‘Besides, it’s not about the dishes but the sustenance that’s been offered on them.’

But as Vashna’s mystical wisdom flowed, Barry had been distracted by a buzzing black ball of blowfly on one of the plates, spinning upside down between knife and fork frantic in its attempt to get airborne.

‘There I am,’ Barry muttered to himself.

Maxwell banged the bottles down on the table with significance, and began rummaging around for something hygienic from which to drink.

Startled by the noise, then pointing like a foot weary traffic warden, Barry snapped, ‘Fellas, go and find a seat in the sitting room and I’ll rinse a couple of glasses.’

An hour later all their banter was witty, to them, and it was in this climate of intoxicated fellowship that Vashna, the group’s self appointed sage, started illuminating his philosophic counsel, ‘Mate, mate, come up town and start a new history … ’

Vashna’s unshaven patches of gorse, on a bony outcrop, never quite cohesive enough to be called a beard, reflected his loose approach to self grooming. Downy white hair curtained unstyled to his shoulders. Clothes, loose fitting colourful aberrations, hung from his beanpole frame. Real name, Spencer, but only used in conjunction with his Broadhurst’s Collectables dealership, giving his business public credence, habitually a debatable trade with dubious earnings. He just happened to spend a hedonistic year or so drifting around India in his twenties, before running aground in a pot infused ashram in Goa on the West Coast, and for the last few decades Vashna had been a self proclaimed custodian of a number of esoterically wise and mystical one liners, invariably not backed up with any substantial research or reasoning.

‘Sarah’s had her story, shortened but beautiful. Now it’s time for his story, a new one,’ smiling at his old buddy, mind roaming in some whisky infused celestial no man’s land while Barry’s eyes remained morosely fixed on the dry glass at the bottom of his fourth whisky.

‘Clever, Vash, very clever.’

‘Haven’t finished yet. That’s when my story starts!’ And, in case his old friend had missed the subtlety of his convoluted insight, which he had, and trying not to look too smug at the same time, ‘You know … the Mystery.’

Maxwell stirred, feeling it an appropriate time to add weight to the profundity of the moment, ‘Baz doesn’t need bloody mystery. He needs to come up town and get a mistress with a nice pair o’ pups.’

Barry wasn’t sure if Vashna’s wordplay was taking the piss, but it really didn’t matter, his good hearted intentions combined with Max’s simple vulgarity had worked their magic on him once again and he found that he hadn’t forgotten how to laugh. So when Barry woke the next morning the words come up town, first from Melinda, and now these slumped and snoring reprobates, had settled themselves in his head like a mantra. Within the month he’d sold the cottage and bought the rundown apartment on Hobart’s harbourside.

No more visceral reminders, etched like a calling card into his memory of his marriage: the familiar growling squabbles of the ringtail possums in the white peppermints and on the cottage roof after dusk; the honking of the geese and swans on the pond; or the rooster sentinel at dawn. And, at last there was an end to the incessant scratching by the Long Overdue For A Prune Wisteria on the bedroom window on breezy nights.

And now, two years later, they were fading like the echoes of laughter in a forest gully, the peacefully swaying yacht masts around the harbour replacing the tall creaking eucalypts of the countryside, and the hypnotic inky waters of the ferryman’s dock, the reflecting mooring lights and infinite flickering patterns becoming his backyard.

Then a third thing happened.

*

It hadn’t taken long for Kant to be wearied by the social rituals of city life, particularly an encroaching nightlife, only minutes from his apartment beckoning like a gaudy, illusory temptress. Initially, heading for the fleshy strip of Salamanca Place clubs, galleries and bars seemed the easiest way to fill the yawning crevasse that stretched across his heart. But to Kant, these glitzy dens of desire seemed only to spawn a young breed of over dressed, over cologned office workers who congested the fuggy air with their stealthy glances and overly dull inventories of LOL gossip.

Nevertheless it was in one such lair of lascivious grazing, one of Max’s little classics, that Kant met James Mackelroy one evening. Or rather, the twenty years younger, ex Sydney television director recently based in Hobart, introduced himself to Kant, shouting him a beer, before offering him ‘the job of a lifetime with a gold crested salary’.

‘Not sure it’s me you’re after, pal,’ Kant had replied morosely, sipping his beer and wondering if he’d manage to get another expensive stubby of the Belgium Leffe beer out of the conceited out of towner before traipsing back to his apartment for another early night.

Mackelroy had laughed. ‘That’s it! That very unassuming manner of yours I was drawn to in the first place. It’s a rare quality these days. So many talentless hacks out there craving recognition.’

‘I’m sure you’re right,’ Kant replied suspiciously. ‘And when exactly were you … drawn to my manner?’

‘Oh, I’ve been watching your news reporting on the box. It’s serious business finding the right persona. And you have a look attached to that manner, and in the TV show I want you to front, that counts for a lot more than you’d realise. Of course, as director I’ll have to do a little chiselling but you’re almost there,’ Mackelroy said with a devious pat on Kant’s shoulder.

Kant shook his head and smirked. The only look he thought he displayed these days was jaded. ‘Look … James, isn’t it? I’ll be sixty in a couple of years. I’m an old journo milker whose udder’s drying up. To be honest I feel like shit most days, I can hardly get myself to work since my wife died recently, and my greatest pleasure in life is talking to my daughter’s baby. Now, why don’t you look along the bar here and pick out one of these fine young men?’ And momentarily finding amusement in a thought, he added, ‘What about spotted bow tie over there? Pretty sure it’s not me you’re after.’

‘We’ll just have to see, won’t we, Barry Kant? … God, even your name!’ Mackelroy replied, gripping Kant’s shoulder as if the proposal was already a done deal.

Kant did get a second Belgium, and after a third the conversation had ignited something dormant deep inside him. Sarah was gone and only once before in his life had he felt so alone, and in some primal cell in the core of his body he knew this offer could be the antidote he needed to anaesthetise his grief.

Getting more than he bargained for, Kant, in just two years, became a national household name. His life never seemed to be far away from the newspapers, and dominated women’s magazines for months. No more trudging Apple Isle reporting for Barry Kant. The TV icon’s unique television show had smashed all the previous ratings records for National television. The now famous BK Smile, disarming so many early skeptics, had secured him the position as host of the most watched TV reality talk show in the country. The unlikely hit had tantalised the voyeur in society with an alternative keyhole to ogle through, which, according to the ratings was just about everyone.

The tiny island state of Tasmania began to parade its engorged pride relentlessly, Kant’s celebrated image appearing in tourist promotions and a plethora of local product advertising from clip lock fencing to men’s aftershave to Flinders Island goat’s cheese.

The program’s format resembled a chat show, but sounded like an hour long confessional of emotional and psychological collapse with the benevolent host, and depended on a public vote for a winner. The twist came with the cash prize. Not for the best performer with a voice as pure as a lark, or the most inventive mind, certainly not the one with superior survival instincts, or the one capable of devising a delectable, culinary experience. And it didn’t even go to some head bursting brain who could answer inordinately obscure questions about ex prime ministers, fatuous sporting obscura, or agrarian farming practices in the Middle Ages. No, it would be for a wholly unique superlative, the prize of fifty thousand dollars going to the person whose ghastly life story and misfortune was voted to be the worst case. The wretched souls not only agreed to put themselves through the indignity of public exposure but subjected themselves to a final, humiliating question time by a gloating, and in the director’s mind, non too bright studio audience, a cordonbleu recipe for excellent TV devouring.

The show was gladiatorial in its intensity, thumbs up or thumbs down. Nonetheless there was an endless queue of hopefuls happy to divulge their bad luck for some easy money. For some, the mere sharing of their traumas became a purging, Barry Kant becoming their saviour, the compassionate oracle who guided them through their perils of the past with his probing but kind persona that the public warmed to and most ended up adoring. At the end of the first series viewers bombarded the station with texts and phone calls, even the odd proposal of marriage.

There were also the inevitable expressions of outrage. The show was callous and exploited suffering. Simply unfair! One retired Liberal MP had even described it as unAustralian. One mainland newspaper commented that ‘The Barry Kant Show is a blatant manipulation of the already down trodden, particularly the poor souls who put themselves through the wringer to come out at the end, flattened and with nothing’.

Of course, the poor souls who found themselves in the public spotlight were often from a luckless under class who the rest of society had previously not wanted to admit existed in such great numbers in charming Hobart town, and further afield in the broader Tasmanian tourist haven of outstanding beauty. And so it gathered momentum, the ratings soaring higher and higher with the thud of every outrage and the splash of each tear.