Читать книгу The Paradise Stain - Nick Glade-Wright - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Three

Оглавление4.30 am Sunday

Kant woke to the clattering of his alarm clock.

The night’s storm had run out of spite. No excuse now not to have that jog he’d promised himself before visiting Melinda and Rosie. It would be an invigorating start to his birthday and the last day of his holiday. Tomorrow, BKS would encircle him once again. He raised himself onto an elbow.

His glasses had fallen into the creases of the doona over night and become twisted. He tried to straighten and match one arm to the other side. Damn. Inspecting the line of the burgundy toned stainless steel, a shade lighter than his new car, he began to wonder why he’d needed to buy the latest model Audi. ‘Wretched thing spends most of its life parked,’ he mumbled out loud as he changed into his jogging gear.

And when was the last time I wore shorts, with no shirt, and wandered carefree along a beach, bare footed on cool sands?

Apart from visiting Melinda and Rosie during his break Kant had dithered around, never quite organising to do anything substantial. He hadn’t been able to clear his head of the Afghan woman, lugging her pain around with him like a sea anchor, and now it was almost time to go back to work. Abrar Abdullah hadn’t won, and the least Kant thought he could do was drive her back to her home, a three hour trip back to her empty flat. She’d sat silently, insisting she’d sit in the back seat of the car, and on arrival had told Kant he was a good man. As he drove back to Hobart his tears had been acidic with guilt.

The Domain was quiet when he arrived on foot half an hour later.

‘Where the hell did it go?’ he yelled at a row of whispering poplars. ‘No, not the holiday; the last sixty bloody years!’

Kant jogged up towards the tennis centre and back down through the wooded hillside, crowded with pines, spruces and cypresses, like an industrial walkout from the Botanical Gardens on the other side of the hill. Fingertips tingling he caught his breath by the rusty bicycle racks near the Cenotaph before heading down towards the docks, emitting pasty puffs like an aged dragon unsure of what to do with any fire that might still be in his belly.

The apartment felt oven hot. Kant threw open the balcony doors to a cool sea breeze that barged past him and into the interior’s cloying warmth as he watched three sleek cyclists below glide by effortlessly. He glanced down at what was the miniscule beginning of a paunch and huffed, ‘You’re thirty years younger!’ to the swishing blur of colourful body lycra.

Kant showered and changed.

In the kitchen he made coffee, tutting at the granite bench, like his mother used to whenever anyone spent money extravagantly. A pang of something flicked him as he ran his hand over the highly polished surface, a lump of coarse rock once, in a Bulgarian quarry, its rudimentary origins now forgotten.

Is that me? he wondered, his thoughts pressing into the stark back streets of Lutana where he was brought up. He smiled, impressed with his analogy.

It wasn’t so much the soulless rows of cheap government housing where his father Desmond still lived after a lifetime that got to him, but that the old man’s scope of desire was embedded in a way of life that neither allowed the new in or the old to be reinvigorated. Many applauded this as being happy with one’s lot . But, inside, Kant cringed at the utter waste of potential for his father’s lifetime. Kant’s fabulous new home, not fifteen minutes’ drive through the city, might as well be situated on the pinnacle of Frenchman’s Cap on the wild West Coast for all the times he’d had a visit from his father.

Desmond had visited only once, coerced into coming for drinks when the show started two years ago. One of Kant’s cameramen had gone to pick him up.

‘You done all right for yourself,’ his spindly old dad had said, intimidated by the marvellous world his son now inhabited. He had gingerly caressed carefully positioned ‘objets’, palmed the warm floor tiles in the bathroom, counted the number of colour coordinated pillows on his son’s bed, and inspected the kitchen work surfaces, with disbelief at the unmitigated extravagance.

Life was a procedure for Kant senior, like the smelting of aluminium, a malodorous process he knew all too well from his forty eight years’ labour at the Electrolytic Zinc Company, just a short walk from his home. Sarah’s death was ‘spilt milk cobber’. Not as an insensitive summation but fathomable like an inconvenient factory mishap. Almost Buddhist in its simplicity Barry had tried to rationalise positively at the time. After the young Barry had graduated with honours at the university in journalism and political science, his father’s wisdoms, which had been the family’s mainstay, carved from a myopic existence, seemed to become obsolete as academia shoved a wedge between father and son’s capacity to converse at any great depth. Any paternal offerings became safely wrapped, clichéd ingots, excusing him from any uncomfortable intimacy that might arise between them, something Desmond had never experienced with his own father. Besides, it was unmanly.

Three Message Received s had come up on Kant’s iPhone display while he was in the shower. The first was from Vashna, who sang in a high pitched southern accent the first line of a Neil Young song, ‘Old man look at yourself’, omitting to sing the second line, pointedly distancing himself further from his friend’s age. The next was a voice message from Rosie, who giggled whilst Melinda endeavoured to coach her as to what she could say. In the end she managed, ‘Gampa’s birth day …’ before the rest of the message became swamped in chortling.

The third text read, ‘woch your back fagot’. Kant instinctive ly deleted the message.

Misspelled or ‘text’ spelling? he pondered, intrigued by this deterioration of language. Negative calls and anonymous malicious pranks were usually the method of choice for denigration of BKS. He put it down to an inevitable consequence of success, never quite bad enough for the police to get involved. But these messages felt personal and always left a scratchy residue at the back of his mind.

After the success of the first series, the rapid adoption and hip use of the BKS acronym by the public was ‘a gift from a greater power’, Mackelroy had elucidated, as if he’d had a direct line to the Creator. It wouldn’t have surprised Kant if his self possessed director had.

James Mackelroy’s head wasn’t shaved as a reaction to a receding bald patch. No way. His cranium was a faultlessly sculpted classical manifestation, tanned and polished like his self opinion, positioned elegantly on a lithe body that would have mingled effortlessly in an Olympian athletics squad of marathon runners. Quick witted and shrewd, qualities he’d sharpened in Sydney’s cut throat TV industry. Mackelroy was wholly ambitious as far as BKS was concerned. Kant’s considered reserve was a crucial counterbalance for his director’s impulsiveness.

Over the two years the two men had become accommodating friends, almost by default, spending more time in consultation about the show than was probably healthy, drinking gallons of perilously strong coffee together at the station whilst debriefing after each new contestant had run the gauntlet. It was an alliance constructed primarily on Mackelroy’s steely belief in the show’s controversial format, and his absolute confidence that Kant played a huge part in its success.

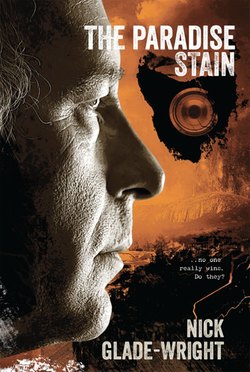

One reviewer had compared Kant to Michael Parkinson, whose smooth interviews “were undemanding because his guests are all celebrities”. But Barry Kant “has the uncanny ability to make distraught individuals feel at ease about articulating their worst nightmares, degrading abuses and horrific losses to an anonymous studio audience and hundreds of thousands of home viewers. Or is that millions now? On the small screen Barry Kant’s kind face, altruistic brown eyes and luxuriant mane of silky grey, somehow seem to make broken souls feel worthy and at ease in his presence, as if they are alone in private consultation with a judicious oracle” .

Life for James Mackelroy, single but never short of nocturnal female company, was all about BKS, his baby, and basing it in Hobart rather than Sydney with exclusively Tasmanian contestants kept a perverse edge on the show. It seemed to reflect the dark passages of the island’s history. Mackelroy liked to crow about discovering Kant and grooming him for the position. BKS had injected the success serum into Mackelroy’s veins, transforming people’s misfortunes into dollars, lots of them.

‘BKS! You can’t buy this sort of marketing. It’s pure adulation. We’ve created a popularity avalanche in the suburbs with your smile and Rex Harrison good looks. Well, your own good looks really. You really are The Man BK! Don’t get me wrong, you prick, but this is the height of … it’s a fucking triumph! We’re up there now,’ Mackelroy, exuberantly drunk, had rambled, while pointing to some mythical nirvana in the ceiling, his zeal exploding like firecrackers at the celebration drinks after the second series had finished.

BKS’s first two seasons had made a devastating impact on the TV ratings of the conventional current affairs programs with their banal, repetitive social docos. And after the third ten week season, several reality shows, with their puerile, mind numbing activities, were sent scuttling back to their drawing boards. Nobody had expected it, least of all Kant, who never forgot his humble beginnings reporting for the Mercury news paper at sheepdog trials, country fairs, traffic accidents and the court of petty sessions. That life was now an impossible solar system away.

‘It’s just like CNN, FBI and NYC; the letters are planetary institutions!’ Mackelroy had rambled on absurdly, foaming bottle of champagne in hand.

‘Don’t forget KFC,’ Kant had thrown in as an aside, exhausted and slumped on a couch underneath a parched and yellowing rubber plant.

The studio set was awash with the entire Nerve Two work force. Everyone, including the cleaners, who had also been invited to the party, laughed convincingly at Kant’s comment.

‘Not so BK!’ Mackelroy lurched on jubilantly. ‘Some of the dishes might be a bit unpalatable but it’s silver service!’

Kant hadn’t meant for such a cynical tone to wash his words. He couldn’t argue with the show’s popularity, or that he had made a significant, if not the lion’s share of the input into the style. So it was with some apprehension that he had begun to have concerns about the ethical nature of the show. Indeed, he even wondered whether he was in fact making a difference at all to the contestants’ lives. He knew that wasn’t Mackelroy’s motivation. Was he merely exacerbating their sorrows with false hope?

Then the third series broke all the records again.

Before BKS, the television station Nerve Two, a small set up in Moonah, just north of the city, had been a fidgety table tennis player frantically struggling for primacy amongst a melee of muscled VFL ruckmen, skipping around, dodging the stamp of giants, wanting to be taken more seriously in a highly competitive arena. The tables finally turned after the success ful marketing of the Barry Kant Show to several mainland networks, resulted in it connecting up to all other mainland states.

*

Kant’s iPhone rang. He picked it up from the kitchen bench. The highland lilt was music to his ears. ‘Vinny! Now there’s a voice I’ve missed hearing.’

‘Och. Sorry to bust in on your last day of holiday, Barry, but I’ve just stumbled on a young laddie, almost literally. A big story and he has a fine way with him too.’

It had been a shrewd move by Mackelroy, after meeting Vince MacLean in Sydney, to offer him a crucial role on the show’s team in the beginning.

MacLean’s reputation as a foreign correspondent, reporting on the Rwandan massacres, and the genocide in Bosnia and Herzegovina, had preceded him. But MacLean was exhausted, burnt out from the years in the field and needed a place to recoup, and maybe never go back to another front line again. The relentless reporting of so much horror had taken its toll in the form of chronic insomnia, his dark nights filled with demons and blood, the screams of innocents and the piercing silence of mass graves.

A haven was what he had longed for. His cousin Hamish told him about the quaint city of Hobart, a peaceful paradise, picturesque and safe from the bad world. So MacLean signed up as crew on a yacht skippered by James Mackelroy, competing in the Sydney to Hobart white water sailing classic. He liked the idea of arriving by sea as the early settlers did. All that salty water and fresh air would surely commence the purge that his soul so desperately needed.

Apart from MacLean’s observational expertise and zeal for uncovering the truth, Mackelroy had been instantly smitten by the lyrical sway of his Scottish accent, one thing the high lander would never lose. MacLean’s immediate answer was a firm no, but the journo in him was a restless spirit and by the time the yacht rounded the Iron Pot light in the mouth of Hobart’s Derwent River he had agreed to Mackelroy’s proposition. His brief, after a well earned respite, would be to locate broken shells, as he’d later refer to them, and encourage them to become contestants in a new reality show.

Finding the right combination of people was time consuming. To begin with MacLean compiled a list of the hearing times at the Family Law courts. He strolled in the parks at dusk and dawn, he hung about at the soup kitchens, hospital waiting rooms, and bus malls in the city, then further out in the grimier suburbs. MacLean engaged with down and outs rummaging for fast food scraps in garbage bins, aimlessly wandering druggies, and eccentric loners who reeked of stale grog and urine and who slept in impossibly windless and murky crannies of the city.

MacLean soon realised it wasn’t only the subjugated under classes that had the rights to dreadful misfortune. The well heeled and the comfortable could also share the fact that ‘shit can happen, any time, to anyone, anywhere’. And no matter how good their intentions to conceal their suffering from the rest of the world, out of dread or disgrace, it would be that hollow, disengaged look in their eyes that would give them away.

Kant took his coffee and sat near the window, sighing loudly for MacLean’s benefit at the proximity of going back to work. ‘Can’t swing a few more days off for me, can you? I was just starting to get the hang of doing nothing.’

‘If I wasn’t just a wee cog in the wheel I’d let you have another year.’

‘Well, I appreciate the thought. So, who’ve you got?’

‘Young African dude, and when I say dude I mean … DUDE!

He’s cool as. But when I found him he was slumped like an unwanted parcel on the steps of the GPO in Elizabeth Street. Saturday morning, round four.’

‘Don’t you ever go to bed?’

‘Och, only in my dreams.’

Kant laughed. ‘You could’ve shared a warm milk with me.’

The pause was long enough for Kant to realise that MacLean hadn’t a clue what he was suggesting.

‘Anyway, thought the laddie was drunk at first but he’d been beaten up something terrible. Said he’d been abducted. Sounded like rednecks to me. Took him up the bush somewhere out the back of beyond and dumped him there to find his own way back to Hobart. Or not.’

‘That it?’ Kant said, thinking this could have waited till he was back at work. ‘Unpleasant as it sounds, it’s just another mugging really. Don’t you think?’

‘Aye, but his big story is what happened to him in Africa. It’s huge. Reaches Tasmania, safe at last, then he gets the locals’ welcome.’

‘Okay, Vinnie. Look, I’m off to see my granddaughter in half an hour so … ’

But MacLean was clearly wound up with the story and needed to finish.

‘He’d escaped a far worse enemy in his homeland. The rebels there, took me back to Rwanda, would make these Tassie rednecks look like a bunch of fairies. Cold blooded killers, child soldiers too, sometimes even friends from the same village. Four weeks fugitive travelling with his siblings at night, hiding in caves during the sweltering days, saw them reach the so called safety of a Ugandan refugee camp. Fifteen he was then.’

‘Fifteen! What’s his nationality?’

‘Sudanese.’ Vince chuckled warmly. ‘Head like coffee bean, and despite what he’s been through he’s got one hell of a smile.’

‘Okay, sounds good. Well … you know what I mean. Book him in, maybe tomorrow arvo. First cab off the rank.’ Kant sighed again audibly, this time for real. ‘Oh, has he got a name?’

‘Has he ever. Ishmael Abraham Liri Mogamba.’

‘Impressive. Thank God for the bible.’

Another of those pauses.

‘How’s the holiday?’

‘Like magic … it just disappeared.’

There was no pause then. MacLean snorted a sympathetic laugh down the phone. ‘Oh, by the way, happy birthday BK!’