Читать книгу Forgotten Islands of Indonesia - Nico De Jonge - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

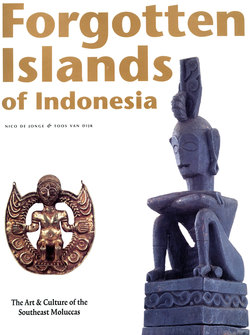

ОглавлениеDetail of the tympanum of a bronze kettle drum. The complete drum is depicted in Photograph 1.2.

Detail of a basta, a long cotton textile originating from India, labelled with a VOC-stamp (PC).

Photograph 1.1. Dongson bronze drum on the island of Luang, weathered by the tooth of time. The maximum diameter is 105 cm; the height is 50 cm.

The roots of the cultures of Maluku Tenggara, as well as those of the rest of the Indonesian peoples, lie hidden in a distant and misty past. Although much research has been done during the last few years to understand these origins more clearly, the available knowledge is still mainly speculative.

Nevertheless some general developments in the prehistory of Southeast Asia which influenced the life and culture of Maluku Tenggara can be indicated with a reasonable amount of certainty. This chapter takes a look at those "traces of prehistoric times" still visible.

The First Inhabitants

Little is known about the very first inhabitants of Maluku Tenggara. It is possible that early inhabitants arrived on foot from the Asiatic mainland during the late Pleistocene era (the so-called “Ice Age”), more than 250,000 years ago. During most of the glacial periods the bed of the China Sea was above sea level, and the Indonesian archipelago was joined by a land bridge to the Asian continent, the "Sunda Shelf.” On Java, remains of anthropoids ("Java Man" or the so-called Homo erectus) dating from this period have been found. We assume that they mainly lived from hunting and gathering products from the woods and sea. We hardly know anything more about the predecessors of the present human inhabitants of the region, and it is a point of debate among scientists as to whether they became extinct, at least in the Indonesian archipelago.

Recent archeologic research makes it likely that the first human beings set foot on the Indonesian archipelago in a migratory wave around 50,000 years ago. (This is approximately the same time that migration began from Asia to the American continents, through another land bridge across the Bearing Strait.) At the time, the Moluccan islands formed part of a land bridge through which Melanesia and Australia were subsequently populated.1

The early Moluccans were frizzy-haired and had a dark skin colour. They were representatives of what is called the Australoid race. From excavations elsewhere in Indonesia it appears that they fed on shellfish, among other foods. It is highly probable that besides the gathering of food, hunting and fishing played an important role. Based on physiological evidence, the present-day inhabitants are thought to be descendants of both these early Austroloids and the Austronesians.

The Austronesians

A process that began circa 10,000 years ago seems to have been decisive for the current picture in many respects. Migrants speaking Austronesian languages set out from a region of origin which must have been located in present-day southern China. These Austronesians, belonging to the so-called Mongoloid race, travelled southwards and gradually started to populate an extending region over a period of centuries. Using rafts, the Austronesians first crossed the China Sea, which had filled again since the last glacial period. They reached, among other places, the island of Taiwan, becoming the ancestors of the present-day aboriginal inhabitants. Research of physical anthropology and linguistics shows that the migrants then sailed to the Philippines, and consequently on towards the western and eastern islands of the Indonesian archipelago. It is assumed that they were present on the Moluccas about 4,500 years ago— during the Neolithic or late Stone Age.

The arrival of the Austronesians caused a complex situation in different parts of the Moluccas. Racially, for example, the inhabitants of many Moluccan islands can not be classified in a simple way. They resemble both the Australoid and the Mongoloid types; hybrids appear in differing degrees per group of islands. The linguistic situation also shows traces of a distant past. Both on the northern and southeastern Moluccas not only Austronesian, but also older, non-Austronesian languages, are spoken (see the Introduction).

The complex situation on the Moluccas can largely be explained by their location: they may be considered a transitional region constituting the periphery of the Austronesian wona, because, in general, the Austronesians did not migrate to New Guinea and nearby Australia, already populated by the earlier Austroloids. Nevertheless, there are indications from eastern Indonesia that Austronesians traveled further east to populate other parts of Oceania.

With the arrival of the Austronesians, many new cultural forms and traditions made their entry. These cultural forms soon became dominant on many Moluccan islands and have been maintained up to the present day. From linguistic research, it appears that the population, besides hunting and fishing, began to develop pastoral activities of pig and chicken breeding. Moreover, agricultural activities were developed; tubers and bananas were cultivated as well as coconut and sago palm trees. In addition, the inhabitants began to use shifting cultivation, an agricultural method utilised for dry rice cultivation.

Photograph 1.2. Dongson bronze drum from China, probably the cradle of metal culture. The maximum diameter is 71 cm; the height is 47.5 cm. The star motif and the frogs depicted are characteristic of prehistoric kettle drums (RMV).

The introduction of certain ceramics and of a quadrangular axe also signified important changes. The latter implement was produced by grinding a large, flat stone into a rectangular shape. Moreover, the arrival of seaworthy boats with outriggers, nowadays a common feature on every Moluccan island, must have been virtually a revolutionary development.

The architecture that until recently determined the appearance of many villages in Maluku Tenggara, might also be considered to be part of the Austronesian tradition: a raised floor structure on piles; decorative gable finials in the shape of crossed horns; and a saddle-backed roof with outward slanting gable ends.2 Due to these, the ridge has the shape of a boat. This architecture suggests that the forms of boat symbolism found in the region (see Chapters III and IV) is also part of the Austronesian heritage.

A number of ideas connected with the function and architectural style of the house are still found on the islands today. Data from western Indonesia suggests that the Neolithic Austronesian immigrants were organised in tribes or groups of related families. Each tribe, as a visible symbol of its community, often owned a large, communal house on piles.3 The house, which had been built by the founders of the tribe, presumably played an important role as a ritual centre of ancestor worship. The building was probably decorated with hunting trophies, which propagated the status of the group. In Maluku Tenggara both these religious and social functions are still connected to many family houses.

Cave drawings on the Kei islands suggest that the Austronesians did not limit their display of prestige to their buildings. Near Dudumahan and Ohoidertawun on Kei Kecil, several drawings have been discovered. According to archeologists, these represent the so-called Austronesian rock art style. Each drawing was made to bear witness to a victory in a sea battle.4 Besides human figures and body parts, figurative signs and boats are depicted.5 The drawings have an estimated age of 2,000 to 2,500 years. They were made during a timespan when attainments of the southeast Asian continent were once again adopted on the islands, the most significant of them being the knowledge of metal working.

The Metal Era

The arrival of the Austronesians is not the only prehistoric development that has left its traces. From research it appears that a large number of Indonesian islands, among them the Moluccas, were part of an extensive Asiatic trade network during the first millenium B.C. This gave rise to a lasting contact situation with other peoples and about 2,500 years ago this must have led to the pervasion of the bronze and iron ages on the archipelago. It seems that the cradle of the metal culture, just as the region of origin of the Autronesian traditions, lay in present-day China.

It seems that the spread of the new culture across the Moluccan islands was effected without many detours. Among other things, large bronze kettle drums—usually called Dongson drums from an excavation site of bronze objects in present-day Vietnam—are cultural manifestations from the metal era. Instruments made on the Asian mainland have been found at various locations on the Moluccas, including eight places in Maluku Tenggara: on the islands of Leti (three), Luang (one), Tanimbar (one) and Kei (three).

Archeologists presume that the drums turned up on the Moluccas some centuries before our era. They relate the drums' presence directly to the spice trade. They base their theory on Chinese sources dating from the Han dynasty (206 B.C. to A.D. 220), in which mention is made of spices originating from the Moluccan islands.6 According to this view, comparable kettle drums found in other locations can be said to mark a prehistoric trade route from present-day South China, via the Lesser Sunda islands, to the Moluccas.

As it did elsewhere in the Indonesian archipelago, the arrival of metal culture led to important changes in Maluku Tenggara. In many places a hierarchical society with leaders, freemen and slaves arose, partly due to tribal conquest and the need for progressive labour specialisation. Divested of its sharp edges, this social stratification is still present on various islands (see the Introduction). At the same time, display of status must have received more emphasis. Head-hunting (which was not banned until the end of the nineteenth century) played an important role in the determination of status. The knowledge of metal working led to, among other things, the development of the "lost wax" technique (see Chapter VII). Moreover, weaving and ikat making are also presumed to have made their entry at this time. Despite the introduction of modern ready-to-wear clothing, these arts are still practised in Maluku Tenggara, owing to the great symbolic significance of the cloths (see Chapter VIII).

Traditional Art Styles

The arrival of the Austronesians and the introduction of metal culture are the two main prehistoric events that influence the current picture in the Indonesia archipelago. A final remark may be made concerning the distinctive characteristics of the local art. It is usually assumed that both Austronesian culture and the metal culture had their own, characteristic formal or artistic "language." The style considered to be connected to the Neolithic is typified as "monumental symbolical" and is characterised by large-scale representations of humans and animals. The style connected to the metal era, especially to the bronze culture, is called "ornamental phantastical." The latter is more decorative in nature and holds the spiral form as one of its main motifs. This style has, for example, been found on the Dongson drums. They are often covered from top to bottom with decorations of curved lines and spirals and extremely stylised humans and animals (see Photographs 1.4 and 1.5). This "ornamental phantastical" style can as well be called the "Dongson style."

It must be noted, however, that relating art forms to the prehistoric cultures of Indonesia has become a matter of dispute. Recent excavations of ceramic materials reveal that the "Dongson style" is probably much older than the metal culture itself.7 For that reason no precise assessment as to the age of the traditional art styles of Maluku Tenggara can be made.

Photograph 1.3. Remnant of the tympanum of a bronze kettle drum in the village of Ami Das on Tanimbar. The name of the matching drum is ibur riti, "copper sack." The exact measurements of the drum are unknown.

Photograph 1.4. Picture of fragment of a bronze kettle drum showing a peacock figure, found on the island of Leti.

Photograph 1.5. Rubbing of a part of the tympanum of a kettle drum, found on Kei, showing flying birds and hunting scenes, among other things. On the tympanum were four bronze frogs (see Photograph 1.2).