Читать книгу Forgotten Islands of Indonesia - Nico De Jonge - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

MALUKU TENGGARA: THE FORGOTTEN ISLANDS

Maluku Tenggara, the Southeast Moluccas, is the name of a chain of islands in the east of Indonesia which stretch in a gentle arc over a distance of almost a thousand kilometres between Timor and New Guinea. The islands he between the easterly longitudes of 125° 45' and 135° 10' and the southerly latitudes of 5" and 8°30' and have a total land surface area of 25,000 square kilometres. Administratively, the region is part of the province of Maluku, which consists of three districts (kabupaten); from south to north, Maluku Tenggara, Maluku Tengah (Central Moluccas) and Maluku Utara (North Moluccas).

Maluku Tenggara is a sparsely-populated, isolated area and in many respects it lies on the periphery of the Indonesian archipelago. It has 288,248 inhabitants (1990), which amounts to a population density of less than twelve inhabitants per square kilometre. Large parts of the region are very difficult to reach, notwithstanding improvements in the infrastructure in recent years. Only the eastern islands have airline links with the outside world (Ambon). The western islands can only be reached by boat and only then with difficulty.

Tourists seldom visit the area. It lies far from the beaten tourist paths. The only Westerners to have visited the islands for long periods of time during this century have been Dutch administrators and military personnel, scientists from all over the world and missionaries of various persuasions. In the last two decades western Maluku Tenggara has been practically cut off for long periods from the outside world as a result of the Indonesian invasion of East Timor in 1975 and the war which followed.

The isolation of Maluku Tenggara, however, is just as much an inheritance of Dutch involvement in the islands. Before the arrival of the Dutch in the 17th century, the Southeast Moluccans had lively trading links with places both inside and outside the region. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) put a violent end to that with disastrous consequences for the local economy. Despite a relaxation of the restrictive regulations during the latter period of colonial rule, the economy did not recover, nor were there improvements in external relations.

In fact, with the departure of the Dutch contact between the remote region and the outside world was reduced to almost nothing. Becoming part of the Republic of Indonesia, the government of which is situated in faraway Jakarta, did not substantially change the isolation of the "forgotten islands."

A tiny part of Maluku Tenggara: a coral island in the Banda Sea.

Disappearance of Cultural Objects

The Dutch presence in Maluku Tenggara also had far-reaching consequences in the cultural field. The pacification of the area and the introduction of Christianity at the beginning of this century went hand in hand with— among other things—forced resettlement of complete village communities and the suppression of the important cult of ancestor worship.

The collective exertions of the government and Christian missionaries had disastrous consequences for the traditional material culture. It was the Protestant missionaries, in particular, who proved to be fanatical in the destruction of ancestor statues. Those which survived were "appropriated" by art collectors, among them both Protestant and Roman Catholic missionaries. Payment sometimes consisted of expensive goods such as axes or a priest's robe, but often nothing more than, for example, a little tobacco. These "exchanges" did not always enjoy the full endorsement of the population and were sometimes concluded under coercion.

Later this century, collectors came across other cultural manifestations which, like the wood carvings, were evidence of a unique artistic, appreciation. This particularly concerned the products of sophisticated goldsmiths and the rich weaving tradition of Maluku Tenggara which, in addition to the wooden statues, became highly-desired collectors' items. Even sacred heirlooms which, thanks to their ancestral powers, protected their owners from calamity and which traditionally only left the house in an exchange of gifts between families, found new owners. Though the export of such pieces is now forbidden, poverty still forces families to sell them.

Within the space of a century the population of Maluku Tenggara was robbed of a significant part of its cultural heritage. Nowadays, a great number of unique cultural objects can only be admired in museums and in private collections. In general, these are regarded as among the most fascinating to have come out of Indonesia. They are unknown, however, to a wider public, because an exhibition or a published work specifically directed at the culture of Maluku Tenggara has until now never been realized. In this respect, too, one can rightly speak of the "forgotten islands."

The Content and Arrangement of this Book

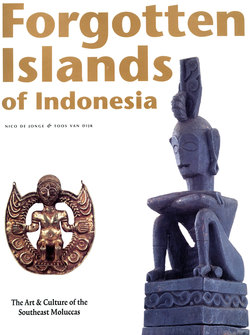

The void has now been filled by this book and by the special exhibition of the same name which opened in October, 1995 in the Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde in Leiden in the Netherlands. The book is divided into three parts and offers a survey and description of the traditional culture of Maluku Tenggara. In addition to the objects which have almost wholly disappeared in the region itself, such as ancestor statues and jewellery, attention is paid to the products of the weaving, plaiting and pottery-making traditions which have always flourished in the islands.

In the descriptions, the traditional significance of the objects within the Southeast Moluccan culture is dwelt upon comprehensively, as far as possible, the pieces are set in their cultural context. Boat symbolism, which permeates practically all southeastern Moluccan cultures, and ancestor worship, which is at the heart of the traditional religions, function as important frameworks. The discussions of these, brought together in Part II, form the core of the book. In order to do justice to local differences, a distinction is made between the eastern and western islands. The cultures of the islands between Timor and Tanimbar, for example, were characterized by a great fertility ritual which did not take place in eastern Maluku Tenggara. Moreover, in order to measure the richness of the island cultures as broadly as possible, a separate line of approach is followed for each region. A thematic approach has been chosen for the western islands, while a more geographical oriented approach has been followed for the eastern islands.

In treating boat symbolism and ancestor worship, conceptual dichotomies come continually to the fore. Heaven and earth, sea and land, man and woman, hotness and coolness, represent poles whose coming together is thought to be of essential importance to the functioning of man, society and the cosmos. In Part III, this dualistic way of thinking is expressed succinctly in the discussion of jewellery, textiles, earthenware and plaited objects.

The descriptive parts are preceded by a historical sketch of Maluku Tenggara (Part I) in which attention is devoted to both the prehistoric, as well as the more recent, past.

The coastline of the island of Marsela, Babar archipelago.

THE LAND AND ITS INHABITANTS

Administrative Divisions

Maluku Tenggara consists of a number of separate groups of islands. The biggest of these are the Aru, Tanimbar and the Kei archipelagos, all lying in eastern Maluku Tenggara. Under Dutch administration these three groups of islands were known collectively as the Southeast Islands; the other islands were known as the Southwest Islands. These names refer to the position of the islands with respect to the island of Banda (Central Moluccas), which at that time was of great economic importance. The distinction made between eastern and western Maluku Tenggara in this book corresponds to the original administrative dividing line.

Nowadays the district of Maluku Tenggara is divided into eight sub-districts (kecamatan). Five of these— Pulau-pulau Aru (Aru islands), Kai Besar (Greater Kei), Kai Kecil (Lesser Kei), Tanimbar Utara (North Tanimbar) and Tanimbar Selatan (South Tanimbar)— lie in eastern Maluku Tenggara. Pulau-pulau Babar (Babar islands), Kepulauan Leti (Leti archipelago) and Pulau-pulau Terselatan (the Southern Islands) lie in western Maluku Tenggara. Tual, in the Kei islands, is the capital of the Maluku Tenggara district.

Administratively speaking, the islands of Teun, Nila and Serua belong to the district of Maluku Tengah (Central Moluccas) but because of their great cultural similarities with the more southerly islands, in this book they are regarded as being part of the southeastern Moluccas.

Natural Conditions

The landscape of Maluku Tenggara is extremely varied. Some islands are mountainous, with peaks of 400 metres on Wetar, 650 metres on Moa and 868 metres on Damer. Others, such as the Aru islands, the highest point of which is only 70 metres above sea level, are fairly flat. Green, forested islands lie close to bare rock formations. Rugged, rocky coastlines, plunging steeply into the sea, contrast with beautiful white sandy beaches. A savannah-like landscape, featuring here and there tall Mi-palms (Borassus sundaicus) is characteristic of the interior of most of the islands. Kayuputih-forests (Melaleuca Leucadendron L) also appear. The coral-rich coasts are girdled with coconut palms (Cocus nucifera).

The Kei islands, paradise on earth.

Geologically speaking, two types of island, corresponding with the same number of "island arcs," can be distinguished. What is known as the Outer Banda arc stretches from the Leti archipelago in a northeasterly direction through Luang, Sermata, the Babar, Tanimbar and Kei islands and then runs in a northwesterly direction through to Seram (Central Moluccas). The islands in this arc consist of coral and are dry and fairly infertile. Fossilized shells can be found on the high coral rocks, which indicates that these are areas of geological upheaval. The highly-remarkable, layered terraced forms found on some of the islands were created by successive upheavals.

Many smaller islands in this arc are largely deforested and have a dry, almost parched aspect. The alang-alang (Imperata arundinaced) which covers the ground colours the landscape almost red during the dry season. The larger islands are more richly forested and have more water. The sago palm (Metroxylon rumphii) can also grow in these islands.

The Aru islands lying to the east of the Outer-Banda arc also consist of elevated coral but are very different in appearance to the other eastern islands of Maluku Tenggara. Their vegetation consists of mangrove swamps and palm forests. The six main islands—unique in the world— are separated from each other by long, narrow straits.

A smaller, more westerly-lying series of islands forms the Inner-Banda arc. This runs from Wetar through Roma, Damer, Teun and Nila to Serua, and then northwards through Banda (Central Moluccas). The islands in this arc are of volcanic rocks and in most of them the soil is much more fertile than it is in the coral islands. The earth under Teun, Nila and Serua is still moving and in 1978, the government considered it necessary to move the population of these islands to Seram (Central Moluccas).

The flora and fauna of Maluku Tenggara, like the whole of Maluku, form a transitional zone between Southeast Asia and Australasia. It is for this reason that scientists have long felt drawn to this part of Indonesia. The fauna of the Aru archipelago is particularly unusual. The presence of the kangaroo, the bird of paradise and the cassowary in these eastern islands is evidence of their close affinity with New Guinea. In contrast, the fauna of, for example, the western island of Wetar, shows clear Asian characteristics, although the large mammals of West Indonesia do not live here.

The climate of the region is dominated by the monsoons, whose season and direction is determined by the position of the continents of Asia and Australia. The powerful westerly monsoon blows from December to April and this may bring severe storms, heavy rainfall and thunderstorms. After a short transitional period the second rainy season, in which the less powerful easterly monsoon blows, follows from April or May until August The hot, dry season begins in August and lasts until November. Following a second transitional period, the rains of the westerly monsoon break again in December.

The Economy

Maluku Tenggara is a fairly poor region with limited economic opportunities. The population exists largely by agriculture and fishing. In addition, goods are exchanged with inhabitants of other islands.

The population is very dependent on climactic circumstances in all its economic activities. In agriculture, the main food crop is generally planted twice a year—just before the westerly and easterly monsoons. On most islands this is maize. On Aru and Damer sago is the principal foodstuff. The staple that is supplemented by rice, sorghum, root vegetables and pulses and small quantities of green vegetables and fruit.

Failure of the harvest is not an unusual phenomenon on the small, dry, eroded coral islands. Hunger is an almost annual occurrence. The inhabitants of the more fertile islands exchange food for goods such as homemade plaited work. Rice is also obtained from Chinese traders, but money is required for this. Money is obtained by selling copra, shells and other products of the sea to Chinese shopkeepers. Old and new homemade textiles are also offered for sale. Money can also be earned by pearl diving around the Aru islands and by working on Ambon and Seram (Central Moluccas).

The sea always yields a great deal, although the catch is also dependent on the seasons. During the easterly monsoon, for example, a village on the east side of an island cannot harvest much from its fishing grounds.

February and March is the mating season of a little seaworm (Polychaeta). On certain nights coastdwellers trek with torches and lamps to the reef, where the surface of the water is covered with these little creatures. Bucketfuls are scooped out of the water with nets and then eaten roasted or fried.

During the hot season, the fish harvest is a celebration! The wind has died away and sometimes the reef is almost completely dry. The women and children spear fish and collect shells. The men, as elsewhere, set their bamboo fish traps out in deeper water and fish from their canoes. Sometimes a large sea animal is caught—a dugong (sea cow) or a turtle, sometimes even a whale.

In the hot season the smaller islands suffer from a serious shortage of water. Village wells might dry out completely. Cisterns which catch rainwater offer the only relief. Then, instead of water, palm wine is drunk. This is the fermented juice tapped from the flowering stems of the koli palm and the coconut palm. The dry season is pre-eminently the opportunity to brew a strong drink, sopi, from this palm wine. This is done with a simple distillation apparatus made from bamboo. Eighty litres of palm wine produce eight litres of sopi. This drink is indispensible for the traditional feasts and it is also an important medium of exchange for obtaining food.

On Aru the hot season is the traditional time for pearl diving. Pearls, mother-of-pearl and other products of the sea such as tripang (sea cucumber, Holothurioidea) and agar-agar (seaweed) are bought by the local Chinese merchants. Nowadays a few Japanese companies are also cultivating pearls in these waters.

Wild pig and buffalo are hunted in the forests of the interior; in Aru deer and kangaroo are also hunted. On very special occasions the meat of these animals forms part of the festive feast. Domestic pigs are also kept in the village and goats are kept in fields outside the village.

Because of difficult economic circumstances on the islands, large numbers of island-dwellers live semi-permanently on Ambon or Seram (Central Moluccas), or even in Irian Jaya, the Indonesian half of New Guinea. The lack of medical and educational facilities in Maluku Tenggara also induce many to leave. The medical care for an entire island is often in the hands of only a few nurses. The larger islands have a health centre. Opportunities for education have been improved by the authorities in recent years; besides a sekolah dasar or primary school, many villages now have a secondary school.

Tall koli palms are characteristic of the landscape of many islands in Maluku Tenggara. In the hot season fermented, tapped from the flowering stems of the trees, is drunk instead of water.

Language

Austronesian languages are spoken on almost all the islands, as they are in most of Indonesia. The exception is in two villages in the southeast of the island of Kisar, where the inhabitants speak Oirata, a non-Austronesian language.1 The dozens of Austronesian languages spoken in Maluku Tenggara, according to a recent classification, belong to the Central Malayo-Polynesian (CPM) group of languages. The Austronesian languages of the Central Moluccas and the islands to the east of Sumbawa, such as Flores, Sumba and Timor, are also CPM languages.2

The languages spoken in western Maluku Tenggara, 24 in all, are classified as a sub-group of CPM languages.3 The people of Luang believe they are all derived from the ancient language of Luang, which in their eyes was once the cultural centre of this region. The languages of Aru, Tanimbar and Kei in eastern Maluku Tenggara form two separate sub-groups of the CPM group of languages.4 Despite great linguistic heterogeneity, a clear language affinity can be observed throughout the whole of Maluku Tenggara. One striking fact is the linguistic unity of the Kei islands, the pride of the inhabitants.5

Malay was introduced to the region centuries ago through trading contacts. Moluccan Malay is peppered with Portuguese and Dutch words and is still the lingua franca. It has been assimilated into Bahasa Indonesia, the national language of Indonesia which is taught in schools.

A fish trap is set on the bottom of the sea; coral stones are used to prevent it from being washed away.

Religion

According to 1990 statistics, half the population of the Southeast Moluccas (158,107 inhabitants) belong to the Protestant church. About 23 percent (66,770) are Roman Catholics and more than 21 percent (61,360) are Moslem. The small residual category belong to other faiths.

Islam was the first modern world religion to arrive in Maluku Tenggara. From the 15th century onwards, the people of Kei and Aru, in particular, were introduced to Islam though their trading contacts with the Javanese and Malayans. It was only in the second half of the last century, however, that Islam built up a large following, originally on Kei and then on Aru.

Protestant Christian belief came with the arrival of the Dutch in the 17th century. The conversion of the population sometimes occurred in an abrupt and forced manner. The first attempts at conversion failed; it was only at the beginning of this century that Christianity began to make headway (see Chapter II).

From the end of the 19th century onwards Roman Catholic missions were also active, first on the Kei islands and then on the Tanimbar islands. Missionaries of the Sacred Heart—dispatched by the Dutch province of the Missionarii Sacratissimi Cordis Jesu (MSC)—were active there and did a great deal of work in the social and medical fields. The people of Aru were only introduced to Roman Catholicism in the 1960's.

Today, branches of the Moluccan Church, Gereja Protestan Maluku, the successor of the Protestant mission in 1935, are found all over the district. This church practically has a monopoly in the western islands. In addition, there are also Seventh Day Adventist churches in Tanimbar. The Moslems and Roman Catholics are concentrated in the eastern islands. The Dutch Catholic missionaries who worked here have now been largely replaced by Indonesians. The last Dutch bishop of the diocese of Amboina, of which Maluku Tenggara is part, was succeeded by an Indonesian in 1994.

The activities of the mission at the beginning of this century were characterized by the heavy-handed suppression of the traditional religions of Maluku Tenggara. Central to these was ancestor worship. In the traditional notions of the universe the contrast between heaven and earth played a large role. In the past, the cosmic entities were sometimes represented as a masculine sun god and a feminine earth. In a "holy marriage,'' they provided for the continued existence of life on earth.

Traces of old religions and former fertility rites— extremely important on the preponderantly infertile islands—can still be found. Ancient rituals have melded with western celebrations such as Christmas and the New Year's feast Nor is the role of the ancestors a thing of the past! Great influence on the lives of their descendants is attributed to them throughout the islands.

Social Organisations

Southeast Moluccan society, like many others in Indonesia, can be typified as a "house society," in which the house forms one of the most important social units. In former days a single large house built on poles, with smaller annexes, could constitute a whole village. There were also larger-scale village complexes with a great number of houses, however. The villages were situated in isolated, easily-defendable locations, such as hilltops or headlands, and were surrounded by a thick stone wall. This strategic position was to provide protection in frequent violent wars. At the beginning of this century, the colonial administration required the village peoples to settle in new, more easily controllable villages along the coast.

Much has changed over the course of time. In the modern villages, houses built on poles are scarcely to be found any longer and bricks have replaced wood as the basic building material. Moreover, the authorities are attempting to discourage large households consisting of three generations, in favour of single-family households. As a consequence, the traditional rules concerning descent and residence have come under pressure. On Leti, Lakor, Luang, Sermata and Damer, descent was determined for centuries through the female line; after marriage, the man went to live in the family house of. the woman. On Damer this situation has changed and— as on most of the other islands—the male line is sustained. In the Babar islands both principles apply side by side and in various hybrid forms.6

On many islands, the social rank of the man and woman is still of importance in choosing a marriage partner. On Kei, Tanimbar and various islands to the west of Babar, men must traditionally marry within their own caste, on pain of hefty fines. There are generally three castes: a nobility, a middle caste and a slave caste. The middle caste is regarded as the autochthonal population. The holders of the important offices within the village mainly belong to the nobility, certainly in areas where social stratification still holds sway. Offices are inherited. The village is controlled by a headman who is supported in his task by a council of family elders.

SOURCES

Material for this book is derived from a variety of sources, ranging from the reports of Dutch administrators, missionaries and scientific researchers to the dissertations of cultural anthropologists of various nationalities.

In the last 25 years much cultural anthropological research has been carried out in Maluku Tenggara, particularly on the eastern islands. From 1971 onwards Cecile Barraud carried out repeated fieldwork on the Kei island of Tanebar-Evav (also known as Tanimbar-Kei). Susan McKinnon (in 1979 and 1980 on Fordate, Tanimbar), Simonne Pauwels (in 1984-86 on Selaru, Tanimbar) and Patricia Spyer (in 1986-88 on Barakai, Aru) also carried out research. In the western part of Maluku Tenggara fieldwork was conducted in 1986-87 by Sandra Pannell on Damer and in 1981-83, the authors of this book carried out fieldwork on two of the Babar islands.

Despite all this recent work, this book could not have been written without the efforts of three people who in the past made accurate reports of what they saw and heard. They appear time and again in this book.

The fauna of Aru, notably the cassowary, shows dose affinity with New Guinea.

The first is the German ethnologist Wilhelm Müller-Wismar, who was attached to the Museum für Völkerkunde in Berlin and who travelled throughout the area in 1913 and 1914. During his travels he kept diaries in which he entered scientific data and he was also active as a photographer and collector. His most detailed information concerns the western islands.

We know a great deal about the situation on the Kei and Tanimbar islands during the first three decades of this century through the monographs, articles and collections of the Catholic missionaries Henri Geurtjens and Petrus Drabbe who were active in the area as priests of the MSC. Geurtjens worked from 1903 to 1922, mainly on Kei but also on Tanimbar, while Drabbe carried out his duties on Tanimbar from 1915 to 1935.