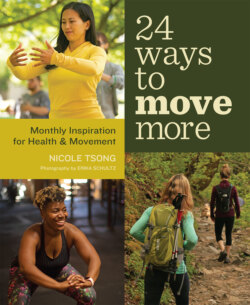

Читать книгу 24 Ways to Move More - Nicole Tsong - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

my

movement journey

ОглавлениеI couldn’t stop grinning, my hair plastered to my head. I was breathing hard, and I didn’t care. I shrieked with laughter as friends bounced me off-balance on a giant blue-and-yellow inflatable tube. I jumped off a tall platform onto a huge inflated landing pad.

Splashing around in a lake on inflatable toys, watching my friend Kristen scream as she flew over the water on a rope swing, cooling off from the intense heat in Texas hill country, I had never felt so strong, so trusting of my body, so happy it could play so hard. Not my adult self, anyway.

I knew, technically, that my strength was above average. For the previous six years, my body had endured long yoga practices several times a week. My legs no longer shook in an extended warrior hold, and I’d made progress on holding a handstand without a wall. For two years, I had taught the sweaty yoga I loved, encouraging my students in a high runner’s lunge or when they attempted a new arm balance. I took teacher trainings where practices sometimes lasted five hours, sweat dripping off my nose onto my mat in downward-facing dog.

Even so, I didn’t feel like a real mover. Sure, I did yoga four days a week. I felt stronger on hikes than I ever had. But I didn’t think of myself as a physical person, surely not an athlete.

But that day, playing at the lake, something inside me clicked. Moving my body in ways outside my norm didn’t feel overwhelming or hard. I laughed when other people bounced me off-balance. I raced around like a kid, convinced I could do anything on the inflatable toys scattered across the lake. I was gleeful jumping into the water.

I felt exhilarated—while moving my body.

The experience etched itself into my memory. A couple of years passed before the notion that moving my body was an instant pathway to feeling happy and joyful cemented itself—when I knew in my bones that my body was not only strong and capable but also that moving it was an essential ingredient to feeling good on a daily basis.

Now, I center my life around this fact: moving my body makes me happy.

If you had told me at age 16, 25, or even 30 that I would love moving so much that it would be a mandatory part of daily life, that I would write a weekly fitness column for The Seattle Times for six years and then turn it into a book dedicated to getting you to bust a move on the dance floor or lace up a pair of roller skates, you may as well have told me I was going to be an A-list movie star.

But that’s exactly what happened. The fitness part, not the movie star part.

A WOBBLY BEGINNING

Perhaps the memory of Dorothy Hamill and her 1976 Olympic gold medal lingered into the early 1980s, so it made sense to my mom that her two girls should learn to fly across the ice. Michelle Kwan was only a toddler then, years away from her Olympic medals. Credit to my mom for being at the forefront of the trend of Asian-American figure skaters.

At age five, the only reason I stepped out onto the slippery ice was to be like my older sister, Ingrid. I would do anything to keep up with her; I even pretended I wanted to ice skate. I didn’t like falling on the hard ice, so I skated carefully, going slowly as I stepped one foot over the other doing crossovers in the little rink where I learned to skate forward and backward and to perfect T-stops.

A few years later, my radio alarm clock went off twice a week in the morning darkness, startling me out of sleep. I hit snooze until my mom opened my door and snapped, “Nicole, you up?” I rolled out of bed and stumbled to the bathroom, grumpy that I had to be up so early to practice.

I donned a teal-green zip-up jacket with matching short skirt, shiny tan tights, and scuffed white skates for private lessons with my coach, Yvonne. Yvonne’s feathered, grayed-out blonde hair looked almost white. She was taller than me, though not by much, and wore a long blue coat with a fluffy white lining to keep herself warm on the ice. She had kind blue eyes and a maternal quality.

Figure skaters showed up early at the ice arena’s parking circle, dropped off one by one, walking over a concrete bridge that crossed a tiny creek. When I opened the doors, the biting-cold smell of ice and dank carpet in the lobby hit my nose. I dropped my heavy duffel bag underneath the carpeted brown benches in the lobby and stuffed my toes into my tight boots, which hurt my feet every time I wore them. I carried clear nail polish in my ice skating bag in case I got a run in my tights.

Once on the ice, shivering, I skated in circles to warm up. Skating fast was the best part of practice. I felt free zooming around the ice. I didn’t have to think; muscle memory took over. I went to the same patch of ice every time, spinning on one foot and learning to waltz jump, skating forward on one foot and landing backward on another. I watched older girls throw themselves into difficult double loops or lutzes, stumbling or falling out of the jump and trying again.

One day, when I was eight, I skated up to Yvonne at the hockey bench where we met for my private lessons. Yvonne looked over the top of her glasses, assessing me.

“Nicole, I think it’s time for you to compete,” she said.

My heart fluttered in my chest. Ingrid was already competing. I envied the confidence of older skaters, heads held high as they danced around the ice in shiny, colorful dresses with shimmery sequins for competitions and the annual ice show. But I didn’t want to compete, not really. Skate alone in front of an audience, with people watching me? I squirmed inside.

“Okay,” I answered, obedient to my coach.

Yvonne wanted me to compete in freestyle solo and also in compulsory skills, showcasing technique. She asked if I also wanted to do interpretive figure skating, a free-form event where skaters are given an unknown song and don’t have a routine.

“No,” I said. I had some limits back then.

Yvonne didn’t push. She shuffled through her tapes.

“First, we have to figure out a song. Then we can create a program,” she said. “Do you want fast music or slow?”

Fast meant I would have to skate faster and jump higher. Fast would push me. Fast sounded terrifying.

“Slow,” I answered.

She chose “Rainbow Connection” from The Muppet Movie. I practiced my routine until I could do it without thinking, the jumps and the spins ingrained, timed to match every swell of Kermit’s voice.

At my first competition, I thought I might throw up waiting for my name to be called. I stood, shaking, at the side of rink. Yvonne rubbed my arms as I waited. Once I was on the ice, posing in my starting position in a new blue dress adorned with white and maroon sequins, the familiar strains of the song floated toward me. I moved, extending my arms side to side and following the program stamped into my muscles.

It took me years to understand the gift of my early years of ice skating and competition. I was much older before I appreciated how it cultivated balance and strength, how I learned discipline from the early morning practices, how the challenge of performing in front of people was my first step to rising into something bigger than myself.

Later, I was grateful for those seminal years of skating, for the ease I still have on the ice, for the discipline I learned working on my jumps and spins, for understanding what it’s like to feel scared and skate out on the ice anyway, and for learning to leave the sport at the end of eighth grade when I was done.

I’M NOT AN ATHLETE

By junior high, my timid kid-self turned opinionated. I didn’t want to skate anymore. It wasn’t cool. Cool kids played soccer or soft-ball. I silently resented my mom for choosing sports for us—we also took ballet—with zero social cachet. I wished she had put me in grittier ones with practical skills, ones that would be social capital in high school.

It felt too late to learn soccer or other team sports, but as I looked ahead to high school, I thought I might be able to catch up with tennis. Our girls’ varsity team had recently won the state competition for large high schools. I had watched the players, admiring their strength on the court, their physicality as they ran after shots and fired hard returns. I wanted to be part of it all. I hoped playing on a high-level team would help me get into college.

My friend Sue had started playing, so I asked my mom to sign me up for tennis lessons at our local raquet club, with the goal of making the freshman tennis team. Sue and I entered tournaments in the summer to get ready to play competitively, and I managed to win a game. I left with a T-shirt and a twinge of pride from the proof that I was better than one other player.

The day of the freshman team tryouts, I clung to Sue’s side. I didn’t know how I would stack up. We lined up against the fence, watching as, one by one, girls went to the baseline and hit ground strokes with the coach.

“Next!” I felt sick, my stomach bottoming out, just like at an ice skating competition.

On the court, I told myself to move my feet, to watch the ball—all of my tennis coach’s instructions. I felt crushed when I hit the ball into the net or out of bounds. I worried my serves wouldn’t go in.

When I got word I’d made it onto the team, relief swept over me. Sue made it, too. When they handed out uniforms, I couldn’t wait to wear the white pleated skirt that signified I was a real tennis player. I had done it; I had made it onto a high school sports team.

I grew into a solid player, in part because I was dedicated, practicing outside on humid, hot weekends during the off-season. I could hit hard when pressed. By my junior year, I made it onto the vaunted varsity team.

I also fell in love with the sport. I felt strong on the green-and-blue courts with white lines, hitting deep forehands into the precise corner I intended or returning a serve with a fiery backhand, sending opponents scrambling around the court. I felt part of something, hanging out on the bus with my friends and cheering on my teammates during long tournament weekends. I felt cool, wearing the bulky red team sweatpants, then heading out to the court to warm up.

I didn’t dare call myself an athlete, however. In my mind, the real athletes ran up and down the basketball court, scored on the field hockey team, or blasted down the track in sprint relays. They owned the hallways with their long, lanky strides. I was a not-so-sporty, school-focused Chinese-American girl, who also played tennis.

“I’m not an athlete,” I whispered to myself, even when our tennis team won third place in the state competition.

I didn’t know it would be one of the most active periods of my life. Once I moved on to college, the strength I had built over years of tennis retreated. I walked a lot; dabbled in tap dance, rock climbing, kayaking, and yoga; and pushed myself into feats like a 50-mile hike. But stress and all-nighters ate away at my strength.

As an adult, any lingering athleticism disappeared into the keyboard at work, where I looked at a screen and wrote story after story at the former Anchorage Daily News. It vanished into the couch as I sighed and watched television after a long day of writing on deadline. It faded into the elliptical at the gym, where my half-hearted 20-minute sessions were dedicated to preventing additional post-college weight gain.

I will give myself credit for the desire to move. I loved hiking, and I chose jobs near the mountains. I lived in Anchorage for a few years, hiking several times a week in the summer and skate skiing two to three times a week during cold, dark winters to keep my energy and spirits up. I pushed my body because I loved the rush of accomplishment at the summit of a mountain, the connection to mental peace brought on by a 360-degree view, a full day of effort rewarded with pizza and a beer.

I asked a boyfriend once if he thought I was an athlete.

“Not really,” he said, shrugging. “Athletic, maybe, but not an athlete.”

The comment stung, but he was saying something I already felt inside.

At that time, I worked out primarily to control my weight. I hoped hiking regularly or skiing would drop the fluffy extra pounds that had accumulated after college. Weight loss was the only goal that kept me going to the gym during the spring and fall, transition seasons when I waited until it was time for my favorite outdoor activities again.

LEARNING FROM YOGA

Weight loss was also my underlying driver to do yoga. When I moved to Seattle to work for The Seattle Times, I needed a consistent way to move that didn’t include the humdrum gym or the traffic battle to hike.

The first time I took a power yoga class, I found my answer.

Back then, the idea of being strong the way I’d felt in high school seemed distant and impossible to rebuild. At 27, I didn’t think I could ever reach the strength I once felt on the tennis court, not when my arms wobbled holding a side plank. I struggled when my legs burned in a warrior. I despised the wheel, a deep backbend.

But with steady practice, I lost a few pounds, which motivated me. I went three times a week and was sore every day in between. I limped around, feeling my quads, hamstrings, and glutes screaming at me from new body awareness and being pushed after years of weakness. I wanted to get stronger; I just hadn’t realized the road to strength had to be walked with trembling legs.

I also started to absorb what my yoga teachers said about judging my body and myself. I realized I had hated my soft, rounded belly my entire life. In class, I bemoaned my lack of flexibility in a forward fold. I envied my teachers’ toned arms and wondered if my arms would ever look like theirs.

For the first time, I saw how hard I was on myself, every day.

In time, my legs quivered less. I could stay upright during balancing poses. I felt comfortable doing handstand hops, even if I couldn’t hold a handstand in the middle of the room. I loved workshops where I learned new poses.

I also was shifting out of the harsh conversations I regularly had with myself. I would start class stressed about my latest story at the newspaper—what I had written or what I’d potentially messed up. I would leave class feeling peaceful, less critical about what had happened that day at work.

Other lessons settled in as I pushed myself into one more wheel or a new pose. Every time I did a pose I didn’t want to, just like the first time I’d skated onto the ice to compete as an eight-year-old, my brain was being rewired. Even if a pose looked intimidating or I was tired, I learned to try it anyway.

My new perspective was simple—I can do more than I think I can.

If you asked my friends, people would say I already lived this way. I moved to China to teach English right after I graduated from college. I lived in Alaska for almost four years, braving frigid, dark winters. I covered Congress at 26 years old. At 27 I got a job at The Seattle Times, my biggest goal yet.

Then, I left a job in the only industry I had ever known—journalism—to teach yoga. Before I gave notice, I sometimes felt immobilized by worry about leaving behind a steady paycheck, health care, and security, not to mention an underlying concern that I wasn’t a very good yoga teacher. Finding the inner strength to walk into my editor’s office and tell her I was leaving and then enter a new field where I was reliant on a brand-new skill set radically changed my self-image. I felt I had finally crushed the voice in my head that told me I couldn’t do big, challenging things.

FIT FOR LIFE

When the editor of Pacific NW Magazine, the weekly Sunday magazine at The Seattle Times, emailed me to see if I wanted to chat about a potential writing project, the role of a fitness columnist did not occur to me. Why would it? I had left the newspaper a year earlier to teach yoga. I assumed she wanted to talk about a freelance story.

During our call, she said, “Nicole, we’re looking for a fitness columnist. Are you interested?”

I was flattered—and baffled. It seemed ludicrous for me to write about fitness.

“I’m a yoga teacher,” I told her. “I don’t know anything about fitness.”

A yoga teacher is a perfectly good credential for writing a fitness column, she responded.

Was it? I knew how to do warrior poses. I knew nothing about taking a barre class or lifting weights. I didn’t even belong to a gym.

The idea, the editor said, was to try new approaches to fitness, take classes, and see what evolved.

I researched fitness columns in other newspapers and couldn’t find a columnist who tried a new activity every week; I wondered if there was a reason. I was unsure I could come up with enough ideas to last a year.

But I missed writing. Though I was still enthralled by my new teaching career, my inner writer clamored for me to say yes.

I wrote a column proposal, with ideas including paddleboard yoga, barre classes, and hula hooping. The editors named the column Fit for Life.

The column merged my peculiar mix of skills—writing, a baseline of strength and body awareness, and a willingness to do new things. What I didn’t know then was I had signed myself up for six years of weekly reminders that I could do more than I thought I could. I didn’t know the column would shatter every internal conversation I’d ever had with myself about my body and strength. I didn’t know Fit for Life would redefine my sense of self and reshape my future into one of a forever mover.

All I thought was: Here goes nothing.

CREATING A MOVEMENT-RICH LIFE

Taking weekly classes taught me that if weights or strength were involved, I’d like the class. If there was a competition, I’d want to win. If I was required to run, I’d detest every step, then tell myself afterward it had been good for me.

I learned that my yoga strength could carry me only so far, like when my brain overloaded from dance choreography in a hip-hop class, or I was sore for three days after bouncing on a trampoline for 30 minutes. For the first couple of years, I was sore. All the time.

I became a perpetual newcomer. I took new classes every week; I rarely took any twice. It was comical and frustrating, fun and ridiculous. If you haven’t been a newbie in years and are nervous about the prospect of trying something you haven’t done before, you are not alone.

I learned to be cool with mastering nothing. As soon as I caught on to a technique in an intro series, the class was over, and I was off to the next. I was forced to let go of concerns about looking foolish, because it was inevitable. You aren’t good at something the first time you do it, ever.

The column became the real-life version of a constant internal practice: Do a new thing. Get over yourself. Repeat.

Four years into the column, after I had tried hundreds of classes and learned a tremendous amount about how to recover from intense movement and injury, I was—truthfully—a bit smug. I didn’t think there was a whole lot more to discover about movement that I didn’t already know. I had done every permutation of high-intensity interval training (HIIT) imaginable. I’d rowed on open water. I’d learned to breakdance, and I’d swung from a trapeze. I’d smiled during swing dance, and I’d swayed my hips to the hula. I’d gotten up at 5:00 a.m. to go to an early morning yoga class followed by a dance party at 7:00 a.m. I’d returned home at midnight after snowshoeing by moonlight.

If you met me at a party and asked if I had tried a particular activity, chances were about 90 percent I had taken a class in it.

ENTER THE SCIENTIST

When I met biomechanist Katy Bowman, who was introduced to me as an innovator in the world of movement, I presumed she would tell me a more detailed version of what I already knew. By then I was subscribing to the approach that had taken root in functional fitness, that the reason to be strong was to carry your kids and live your life. I wanted to be strong! So I, along with so many others at fitness studios, swung kettlebells, did pull-ups, sprinted, and released sore muscles with foam rollers.

I was on the cusp of learning how much I didn’t know. I was about to have a massive turnaround in how I approached movement in my life.

An author, teacher, and podcaster, Bowman studies how gravity, pressure, and friction affect people’s bodies. What’s more, she shows people all the ways they aren’t moving, me included. Say what?

After reading her book Move Your DNA, I saw all the minutes of the day I didn’t move. I had my fair share of hours in a chair hunched over my computer. I added up the minutes spent sitting in my car and the time spent on the couch in the evening as I decompressed or sat at a table eating lunch or dinner.

The more I dug into Bowman’s work, which spans multiple books, years of blogging, and a podcast, the more I saw how rarely I walked. My shoes had heels and inflexible soles, keeping my feet from stretching and getting stronger. I hunted for close parking instead of walking a few extra blocks. If I was early to an appointment, I looked at my phone instead of taking a quick walk.

In other words, I was like everyone else I know—sedentary.

Wait a minute. Sedentary?

Because of my one to two hours of workouts a day, I was “actively sedentary,” according to Bowman.

Gee, thanks?

But Bowman does not tell people to exercise more. Instead, she prescribes broadening your mind to understand movement and how lack of it affects your hips, back, and shoulders. When you understand how much your body is impacted on a daily basis by choices not to move—enforced all day and everywhere by our sedentary culture—then you can find new ways to add movement back in.

Bowman advocates more time outside breathing fresh air and exposing your body to variation in temperature. Go barefoot on grass and rocks. Sit on the floor instead of the couch or chair. Walk a minimum 10,000 steps per day.

History teaches us healthy movement. In hunter-gatherer times, people sprinted to hunt animals; used their hands, shoulders, and feet to climb trees; and squatted to gather berries from low bushes. Their knees, hips, and shoulders had good range of motion; their feet were supple and strong.

In our modern world, water is piped to our house and food is prepackaged at the store. We sit on a couch, and many of us work at a desk. Sitting on a chair means we skip using ankles, knees, and hips to lower down and get back up. Shoes trap our toes, and elevated heels force us into a position that affects our hips and lower back. We walk less and scramble to find time to exercise.

We have knee injuries, shoulder injuries, and lower back pain. According to the US Department of Health and Human Services, nearly 70 percent of the US population is considered overweight or obese. Bowman says, research has identified sitting and lack of movement as the foundation for almost every physical challenge modern humans face—hip issues, cancer, myopia.

Still, we don’t move, not in the ways that will help.

“It’s not exercise you need more,” she says. “You need to move while getting the rest of your life done.”

Many of her suggestions are small and simple, though they were radical to me at first. Slip your shoes off at your desk and stretch your toes. Stand while working instead of sitting. Sit on the floor once or twice a day. Take five-minute walking breaks. Park farther away and walk to your destination.

The US Department of Health and Human Services recommends a minimum 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise or 75 minutes of vigorous exercise each week to help avoid diabetes, arthritis, and heart disease. Regular exercisers get an average of 300 minutes per week. But a hunter-gatherer moved 3,000 minutes a week, Bowman writes in Move Your DNA.

Bowman wants 10,000 steps to be the baseline, not the goal. She likens exercise to eating something healthy so you can have dessert, but a kale salad doesn’t negate multiple crème brûlées. “We can do better than exercise. We need to do more than exercise,” she writes.

For the first time, my usual one to two hours a day doing yoga or Olympic weightlifting or that week’s class for the column felt like underachieving. I took a closer look at the ways I could move more frequently.

I didn’t get rid of the couch, but I did build other approaches into my life. I started sitting on the floor to work. I rolled out stiff feet and tight glutes while watching television. Fitting in 10,000 steps a day became a daily minimum. To rest my eyes, I looked into the distance whenever I was outside. I’ve done 20-mile walks with Bowman, who, in addition to being as smart as a whip, is a lively and warm human.

This approach also helps me from getting stuck in the idea I have to “exercise” every day. It’s helped me see that when I am sluggish or mentally stuck, all I need is a short walk to invigorate me. If I don’t have time for a class, I have other ways to move that are quick and that I can do nearby or at home. Movement has always been a way I connect back to myself, and doing it more throughout the day keeps me steady and anchored.

But my happiest days, my favorite days, still include a fitness class. I go to Olympic weightlifting sessions, I take a dance class, or I do yoga because they make me feel strong, energized, myself. The deeper shift showed up in the gaps in between, where my new normal and habits changed to walking, to sitting on the floor, to wearing minimal shoes.

Nowadays, I aim to move my body, all day, every day.

WHAT ELSE CHANGED?

For the next two years, I continued taking classes for my Fit for Life column while also working general movement into my life throughout my day, every day. And then, six years after it started, my weekly column ended. A look back at the final class count astonished me—I had tried roughly 300 classes. As I reflected on what I’d learned, I realized how much I had changed in those six years, and especially the final two.

When the column started, I had never tried high-intensity workouts. I didn’t know hauling myself up 150-foot trees using climbing gear was possible. I didn’t know how much I loved to dance. My original goal had been simple: come up with enough ideas to last a year.

In my early days, I avoided water sports. Now, I relish jumping into the bone-chilling cold of an alpine lake on a hot August day. I like challenging my body to adapt to the dip in temperature. It’s refreshing!

I have not gotten over my dislike of running. I gave up making myself enjoy endurance sports and embraced Olympic weightlifting, channeling my fast-twitch muscles into an aggressive hip snap for the snatch and clean and jerk.

I was 34 when I started writing the column, and I closed it out just after my 41st birthday. I was the strongest I had ever been. Even during a short stretch when I had surgery and was limited to walking for eight weeks, I trusted that if I worked hard enough, my strength would come back. Two months post-surgery, I was back on the weightlifting platform and doing handstands in yoga.

I had become a walker. Even now, walking is a nonnegotiable part of my day. Ten thousand steps, or roughly four to four and a half miles, are mandatory. The best days are when I hit 15,000 to 30,000 steps. I have uneven, forested trails nearby and choose the benefit of the soft trails and green canopy over walking on sidewalks during my twice-daily walks with my dog. If my brain stalls at my computer, the best medicine is to get up and walk.

Influenced by Bowman, I switched fulltime to minimal shoes, going for flat and flexible in my everyday shoes, stretching my Achilles and feet. Now that I’ve transitioned from thick hiking boots to barely-there sneakers (see “Hike in Minimal Shoes” sidebar in Month 3), a knee that had nagged me my entire adult life when hiking down steep inclines doesn’t even murmur now. I credit my strong, sturdy feet.

Other parts of my life have shifted too. When I travel, I walk no matter what, even in 100-degree desert heat in July in Phoenix. I wear a hat to shield my face and remember my body can tolerate a wide range of temperatures. I always walk whenever I can on vacations.

I never question my strength. I may feel awkward as all get out taking a dance class, or I might dislike an indoor cycling class, but I never wonder if I can do it.

By taking new classes, pushing my body day after day, playing ultimate, or learning to trail run, I’ve handled whatever was thrown at me. Was it always pretty? Nope. Was I going to master it in one go? No way. Was I going to feel a little silly? Certainly.

Was I going to have fun? Absolutely.

My delight in pushing my body was real, and it still is.

I started the column as a yoga teacher. I ended it as a mover.