Читать книгу Mansell: My Autobiography - Nigel Mansell - Страница 12

Оглавление2

THE BEST OF RIVALS

When I first started in Grand Prix racing there were many top names involved, each of which will always strike a particular chord in the hearts of Formula 1 fans around the world: Niki Lauda, Jody Scheckter, Gilles Villeneuve, Didier Pironi, Nelson Piquet, Patrick Tambay, Alan Jones, Carlos Reutemann, Alain Prost, Elio de Angelis, Jacques Laffite, Keke Rosberg, to name but a few. A lot of those drivers were either World Champions at the time or became champions in the next few years. Thirteen of them had won Grands Prix. I was lucky to enter Formula 1 at a time when there were far more significant names around than there are today.

In the late eighties there were only four âacesâ â Ayrton Senna, Alain Prost, Nelson Piquet and myself. Into the nineties and by the end of the 1994 season, Prost had joined Piquet in retirement and Senna had tragically died, so it was down to three: myself and the emerging talents of Damon Hill and Michael Schumacher. The new breed of drivers have not been able to establish themselves yet, either in the record books or the publicâs perception, and their reputations remain unproven.

The biggest thing for a driver is to gain worldwide recognition and respect and you only get that by doing the job for a number of years and getting the results. You need years of wins and strong placings to establish your name. No disrespect to any Grand Prix driver, but until you have won five and then ten and then fifteen and then twenty Grands Prix, you cannot be considered an ace.

Only three drivers have won more than thirty Grands Prix: Prost, Senna and myself. If you go down the list of prolific Grand Prix winners, many have either retired or died â Jackie Stewart, Niki Lauda, Jim Clark, Stirling Moss, Graham Hill, Juan Manuel Fangio, and so on. One reason for the gulf between the big names and the rest is that in the late eighties, when much more non-specialised media became interested in Formula 1, they could only focus on a limited number of drivers and so instead of looking at seven or eight drivers, they focused only on three and put them under the microscope. Because Prost, Senna and I were winning everything, the non-specialist media totally disregarded some other good up and coming drivers.

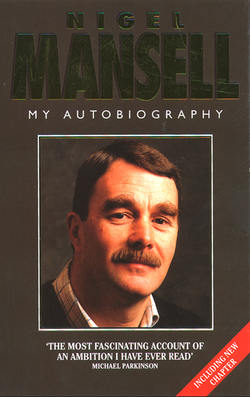

When I decided to commit myself to motor sport and to strive to be World Champion, I knew that I was an outsider. I was told at the beginning of my career that with a name like Nigel Mansell I would never make it to Formula 1 or make anything of myself in life. I guess I proved them wrong.

In the early stages of my racing career, as I struggled to scrape together the money to pursue my dream, I became aware of a group of drivers whom I nicknamed âThe Chosen Onesâ. These are the people who are expected to make it, to go all the way to the top. The phrase âfuture World Championâ is bandied about with reference to these people, some of whom do make it, many of whom donât. What unites them is that they have the backing and support of wealthy sponsors or corporations and their path to the top is marked out for them. Influential people in the industry back them and tip off the magazines and newspapers to âkeep an eye on this boyâ. Consequently they get a lot of publicity and this pleases their sponsors, who put in more money. If youâve got the money in this sport, you get the best equipment and on it goes. You can understand why these people are âThe Chosen Onesâ, because in this sport you need a lot of money and support to make it and people are unwilling to back outsiders, like me, who have no money.

But the unavoidable truth of the sport is that it takes talent to win races and championships. You cannot compete at the highest levels without having that talent. When I was coming through the ranks, âThe Chosen Onesâ were drivers like Andrea de Cesaris and Chico Serra. They got huge backing and much ink was put on paper about how they would conquer the world. Yet neither of them won a single Grand Prix. Chico Serra was run in Formula 3 by Ron Dennis, now the boss of McLaren, and they used to have their own video cameras out on every corner so they could analyse what the car was doing. And yet Chico came up to me on the grid one day and said, âExcuse me Nigel, could you tell me how many revs youâre using at the start?â

The history of the sport is littered with examples like this and itâs still going on today. Maybe there is a young outsider out there who is struggling to get the money together but has the self-belief and the determination never to give up. If there is, I hope he draws strength from this story and I wish him the best of luck. Heâs going to need it.

Others, like Ayrton Senna, Alain Prost and Michael Schumacher were more successful. None of them spent much time in poor equipment and all of them were well financed along the way. The main thing which united them, however, was their supreme talent. It annoys me when I read that I do not have the natural talent of a Senna or a Prost and that I âmade myselfâ a great driver. Firstly, you cannot run with, let alone consistently beat guys like that unless you have as much talent and, secondly, I have the satisfaction of knowing that two of the sportâs greatest figures, Colin Chapman of Lotus and Enzo Ferrari, both considered me to be one of the most talented drivers they had ever hired. Their opinions speak for themselves.

Part of my problem was that I spent many years in number two driver roles and in terrible cars. It wasnât done deliberately, it was just a set of circumstances. Lotus gave me an opportunity to show a little of my flair as I led races, qualified well, and got on the podium a few times, but when I was given a real opportunity in 1985 at Williams I flourished, winning two races in my first season; and in my second year I won seven more and almost took the championship.

When the opportunity presented itself I grabbed it, but it took a little longer to come to me than it did to some of the better supported drivers.

Over the years I have driven against some of the legendary names of the sport and some of my favourite memories come from knowing and racing against these characters.

Driving as team-mate to Keke Rosberg with Williams in 1985 was a great experience. Whenever Keke did anything he did it at ten or eleven-tenths. He was always driving totally flat-out, and he had unbelievable commitment. Iâll never forget his qualifying lap at Silverstone in 1985, when he set the first 160mph lap, the fastest ever lap in a Grand Prix weekend. If Keke wanted to go anywhere then he would do it by the most direct route. He was a real flair driver, instinctive and courageous. He didnât know much about the technicalities of a racing car and didnât spend too long working on the finer points of set-up. If his car was balanced, he would simply drive the wheels off it and that was always terrific to watch.

Before I joined Williams in 1985 Keke said that if Frank took me on he would leave. He had a very negative opinion of me, based on hearsay which at the time was coming from Peter Warr, who had taken over from Colin Chapman at Lotus and who was spreading all sorts of stories about me around the paddock. When Keke and I got together I could tell that he was working under duress, but to his credit his mind was not completely closed and as the months went on he clearly formed his own opinion of me which was much more favourable. From then on our relationship was terrific. He showed me a lot of things and I learned a lot from him about how to carry myself as a professional racing driver. He was fantastic with the sponsors and used to give really engaging and entertaining speeches to the corporate guests in the hospitality suites before a race. I watched him and learned from him.

We only spent one season together in the same team. The South African Grand Prix at Kyalami was the second to last race of that season. Iâll never forget it and neither will he. I was on a real high because I had just won my first Grand Prix a few weeks before at Brands Hatch. I grabbed pole position and afterwards he came up to me and said, âNow I know why you are so fast and why you have pole position here. It is because you are a complete bloody maniac. I watched you run right up alongside the concrete wall for fifty yards. Youâre mad.â He had a huge grin on his face and we both fell about laughing.

It was a hairy run, but it served its purpose and won me pole position. Keke could see that my confidence level was really up. The car was working well, the team was giving me full support and I had learned the secret formula for winning Grand Prix races. He could see that I was like a starving man who has just worked out how to get into the fridge. Nothing would stop me. The race was close. He and I were both under pressure from Senna and Prost. I won, making it two in a row. Keke has described it as one of the hardest races of his career and I would agree with that.

Gilles Villeneuve was a great driver, but more than that he was a great friend. We got on really well. When I first arrived in Formula 1, he took me under his wing and showed me a lot of things about how the Formula 1 game worked. We shared a lot of confidences. Like me, he was a plain speaking man and he always said what was on his mind. I understood where he was coming from and respected his judgements on people in the paddock. My arrival in Formula 1 coincided with the power struggle between the governing body and the constructors and Gilles encouraged me to go to the drivers meetings and take an interest in what was going on. He helped me a lot.

We had a lot of fun together, both on the track and off. The racing was pretty raw and competitive in those days and it was always cut-throat. The best man and the best car won on the day, but we had some massive scraps and then we would talk and have a laugh about it afterwards.

His road car driving was legendary and there are some great stories about him told by people who travelled with him at enormous speed on road journeys. I also travelled with him in his helicopter and because he was so fearless and such an accomplished person he could carry out the most extraordinary dives and manoeuvres as a pilot.

Gilles was a very special man, who lived his life to the full and who always drove at the limit. Looking back, the best race I had with him was at Zolder in Belgium in 1981. It was my first visit to the circuit and I managed to beat him for third place to claim my first podium in only my sixth Grand Prix start.

The following year we returned to Zolder for a rematch, but we never had the opportunity as Gilles was killed in an accident during qualifying. It was an awful incident in an awful year. Driving past the scene of the crash, I could see that it was serious as bits of his car were strewn all over the track and the surrounding area. I didnât stop because there were already a lot of people there and the emergency crews had arrived in force. I was practically in tears as I drove around the rest of the circuit, repeating over and over again to myself, âPlease, please let him be all right.â It was shattering blow when I found out later that he was dead.

Gilles has been sorely missed in Grand Prix racing ever since that terrible day. He brought a magic to it, a sparkle, which is what endeared him to Ferrari and the passionate Italian fans.

I was very happy when Gillesâs son, Jacques landed a drive for Williams having moved over from IndyCar, where I raced against him in 1994, straight into one of the two top Formula 1 teams. Itâs a real piece of history and Iâm happy for Jacques. I was slightly amused when I heard he signed because I remembered Patrick Head, Williams technical director saying something about IndyCar drivers being fat and slow ⦠then all of a sudden heâs signed one up!

Another driver for whom I have great respect â and I believe the feeling is mutual â is Niki Lauda. He is a total professional, very analytical, with tremendous courage. He was a superb racing driver who won many races through his intelligent handling of the car.

Niki was very good at getting himself positioned within a team and he was one of the few drivers to get the best out of Ferrari. He told me that if I had used my head differently I would have won more championships and heâs right. If I had been more political I would probably have won two or three more championships, but thatâs just not the way I am. Iâm not the sort of political manoeuvrer that some of my rivals were. Iâm more romantic than that. I like to think that I am what a racing driver should be. I like to win by having a fair race and a fair fight with someone. If there has been some skulduggery in the background which means that a fair fight isnât on the cards then that isnât my scene and I donât think itâs worth as much. Iâve gained more satisfaction from what I have won and the things I have achieved. I do try to look after my interests a bit more these days. But when it comes to politics, Iâll never be on the level of Alain Prost.

Alain Prost is the expert political manoeuvrer. He has won 51 Grands Prix, more than any other driver in the history of the sport, and he has four World titles, one less than Juan Manuel Fangio. You have to respect Prostâs record, but at least one of his titles was won more by skilful manoeuvring away from the circuit than actually out on the track.

Prost almost always had the best equipment available at the time: he drove for Renault in the early turbo days, then switched to McLaren, who dominated the mid-eighties with their Porsche-engined cars and the late eighties with the support of the Honda engine.

Heâs a bit of a magpie. He uses his influence to pinch the most competitive drives. At Ferrari in 1990, Prost worked behind the scenes pulling strings and getting the management of Ferrari and its parent company FIAT on his side. At the end of 1989, Ferrari was my team and I was looking forward to a crack at the world title. Prost came along and tried to ease me out. The ironic thing is that Prost himself was fired by the management of Ferrari at the end of 1991.

When we did race on a level playing field he would rarely beat me. Thatâs why he didnât want to compete with me on equal terms. Getting himself into a position where he doesnât have to compete on equal terms is part of his strength. Thatâs part of the game, but itâs more romantic and far more satisfying for everyone if you have equal equipment and say âLet the best man winâ. You have to be clever to get the car in shape, but to use political cleverness away from the circuit to get an advantage is not good for the sport.

It was disappointing not to be able to take him on in a fair fight either at Ferrari in 1990 or at Williams when he took my seat at the end of 1992. But itâs not the end of the world because I know how good I am. I raced alongside him in 1990 and knew that the only way he could be quicker than me was when the equipment wasnât the same. Iâm not interested in political manoeuvring or in working to disadvantage my team-mate. Naturally, I want success for myself and to win, this is positive, but I donât want to do it at the expense of the person with whom I am supposed to be collaborating. I am simply not motivated like that. Itâs so negative.

In my early Formula 1 days we got on reasonably well and played golf together occasionally, but as soon as I began to beat him on the track and to pose a serious threat to him, he didnât want anything to do with me, which was a shame.

Ayrton Senna was one of the best drivers in Grand Prix history. I was probably the only driver consistently to race wheel to wheel with him and there is no question that he was the hardest competitor in a straight fight; I wouldnât say the fairest, but certainly the hardest. You knew that if you beat Ayrton you had beaten the best.

He was often described as being the benchmark for all Formula 1 drivers. I believe that whoever is quickest on the day is the benchmark and it can move from race to race. Admittedly, because of his qualifying record Ayrton was more often the benchmark than I was. But it tended to move between Lauda, Prost, Piquet, Senna and me.

Ayrton tried many times to intimidate me both on and off the circuit. Once, at Spa in 1987 I told him to his face that if he was going to put me off he had better do it properly. We even had conversations where we started to respect each otherâs skill and competitiveness and agree not to have each other off. But he would then forget about the conversation or make a slip and have me off or hit me up the back. It must have been premeditated, because he was too good a driver to do it by accident.

It was unnecessary for Ayrton to act in this way, but I always took it that the fact he did it to me meant that I intimidated him. Nevertheless we did respect each other. We werenât bosom pals and we didnât run each otherâs fan clubs, but when both of us had anything like a decent car he knew that he would have to beat me if he was going to win and I knew that he was the one driver I would have to beat.

Ayrton was a natural racer and was willing to push the limits. Something terrible happened at Imola. There was no question that he was right on the limit when he went off. Perhaps something let him down on the car. He certainly pushed the limits and enjoyed it. We had that in common, we both enjoyed working on the ragged edge. That was where we would set our cars up and where we would drive when the need arose. If you are an honest professional racing driver that is what you have to do.

On my victory lap at Silverstone in 1991, I picked him up after his car had broken down at Stowe. I could see that he was getting a hard time from the crowd and I know what thatâs like from my own experiences in Brazil. So I thought I would help him get out of a tricky situation. It was amazing the criticism I received after that show of support. One magazine said that I was stupid to do it because I allowed him to see the Williams cockpit and to see what was on the dashboard display. It was so small-minded of them. There are some people who are going to criticise you no matter what you do.

When he won his third World Championship at Suzuka in 1991, I hung around after retiring from the race to congratulate him. Later we had a chat and it was probably the closest we ever got. There was a deep mutual respect between us and thatâs how Iâd like to remember him.

Nelson Piquet was the other big name in Formula 1 during the late eighties. He was my team-mate at Williams in 1986/87, but it was an unhappy relationship. Nelson is a big practical joker with an annoying sense of humour; he also worked at splitting the teamâs loyalties and getting people to side with him.

When he joined Williams in 1986 he obviously thought that he was going to win everything, but I showed him up over the next two years and took a lot of wins away from him. Williams has the capability of running two cars close together because of the very high standard of their engineering and the way that Frank Williams and Patrick Head run things. You still have a number one and a number two driver in the sense that the team leader has priority on the spare car and so on, but the number two at Williams always has a good chance of winning races, as I did over those two years.

Nelson didnât like this and he tried to get Frank to give team orders, something which Frank refused to do. Nelson claimed that Williams was displaying favouritism towards its British driver, which wasnât true at all. To be fair, Nelson was a hard competitor when he wanted to be. He could be devastating on fast circuits. Although I beat him at Brands Hatch in 1986 and at Silverstone in 1987, he snatched pole position from me at both with some very committed laps. In a straight fight and when he felt like it, he was somewhere between Prost and Senna.

Michael Schumacher is obviously going to be the star of the future, but I know less about him. I remember when he arrived in Formula 1 he made a big impact, not least when he and Ayrton had a set-to during a test at Hockenheim. I always said that he was very talented, very quick and brave and perhaps now he is settling down to become a good, if not yet great driver. Winning his first World Championship has helped his cause, but only time will tell whether heâs got what it takes to become a real ace. Unlike some champions heâs not had to struggle as he made his way through the ranks. Whatâs more, he has not had the opposition during his career that many of us had. But all credit to him, youâve got to take your opportunities when you can and he certainly did that in 1994 with Benetton.

I am delighted for Damon Hill that he has been able to come on as strongly as he has. Heâs certainly grown in stature and is getting better all the time. When you drive for a top team with the best equipment and you have the opportunity to win consistently, you can improve a lot as a driver. When I did four races with him as his team-mate in 1994, I honestly believed I helped him and that gave me a lot of pleasure. To my mind, he has all the ingredients to win a World Championship, and I really think heâs ready to win it. The pressure he is under is immense â only drivers at the front know what the pressure is like â and I think the way he and his wife Georgie have come through it is brilliant.