Читать книгу Mansell: My Autobiography - Nigel Mansell - Страница 18

Оглавление7

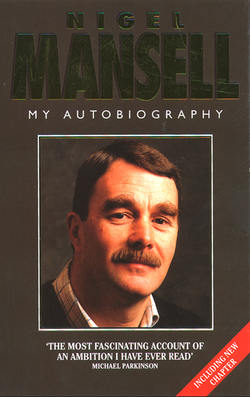

ROSANNE

Nineteen-seventy-eight was without doubt the worst year of my life and by far the lowest time in my racing career. I had been given a lot of false promises and told I would get a lot of support and help which wasnât forthcoming. I was bitter about it, but there was nothing I could do. In many ways the frustration was the worst part; I felt as though I was powerless to stem the flow of disasters and body blows. I wanted to take control of the situation, but I couldnât see a way forward for my career. We needed money before we could begin to look for any solutions.

Rosanne had been the bread-winner ever since I had turned professional the year before and now I had to lean on her even more. She had a very good job and she put in all the hours that God sent. Although a lot of my time was spent looking for drives and for sponsors to pay for them, I carried on working for Peter Wall down in Cirencester, so Rosanne and I were forced to spend time apart, which put a strain on our marriage.

Although we were both very committed to getting on with what we had decided to do, namely my racing career, the awfulness of our situation began to put that commitment into question. When we were together we talked long into the night about the future. Should we abandon our plans? Should I forget about trying to be the Formula 1 World Champion and go back to engineering or should we stick to our guns, tough it out and hope that someone, somewhere would give us a break soon?

We reminded ourselves that what we were trying to do was something you can only do when you are young. We knew that eventually we would want to have children and so we needed to make the most of the opportunities now. In most jobs, you go to your office or place of work each day, do your job and if you like it and the company is happy with your work, you can do that job up until the day you retire. Before I left Lucas I would occasionally thumb through the magazine which the company sent out to all its employees. There were always photographs of people who were celebrating their retirement after years of faithful service. Sometimes the magazine would honour an old gentleman who had been with the company for 40 years. I used to look at the faces of these people and wondered how they could spend almost half a century doing the same job.

They had made their choices of what they wanted to do with their lives and, with Rosanneâs support, I had made mine. Motor racing was calling us and we knew that although we had hit rock bottom, if we didnât dedicate ourselves even more at this time to what we believed we could do, then all the money we had lost and all the sacrifices we had made would be for nothing. It would just be a bad memory for the rest of our lives. I have never wanted the word âregretâ to be part of my vocabulary.

I know how competitive I am and could see that if I stopped racing now I would carry a chip on my shoulder about it for the rest of my life. We turned the situation around by looking at it in a different way. We drew positive lessons from the negative experiences we had suffered. The disasters and the knocks spurred us on to succeed and made us all the more determined not to give up.

Iâm sure that there are a lot of people who, if placed in the same situation, would have given up. They would probably have stayed low for years and would have carried that bitterness and sadness through the rest of their lives. But in Rosanne I had a pillar of strength and together we managed to turn things around.

Unfortunately, renewing our commitment to racing did not put food in our mouths. This was a lean time financially. We had only Rosanneâs salary plus the few quid a week that I earned from my office cleaning sorties to Cirencester. We were caught in a trap. We had only enough money to live on and to pay the bills on our rented apartment. We so badly wanted to take a holiday or just go out for a night to cheer ourselves up, but we couldnât afford to do anything. In the early days of our marriage, before most of the funds were channelled into racing, we used to take holidays abroad. That was out of the question now.

There was maybe an afternoon or a week during this period where we had a great time, but it was so infrequent that you almost couldnât remember it. And usually it was something which was free, like going swimming in a lake. We had sold almost everything so we didnât have any possessions we could enjoy. We used to spend a lot of time walking my parentsâ dog on a great big park called Umberslade. We would walk for hours, chatting and playing with the dog. It became a big part of our routine because it didnât cost anything and we could spend some quality time together relaxing, away from people and the pressures of the telephone and life in general.

Rosanne was so strong. She was just as committed to my racing career as I was, even though she had no family background in racing and had only become aware of it properly when she met me. She did not regard my goal of winning the World Championship as a pipe dream, as Iâm sure many wives would have done under the circumstances. She believed in my talent and she knew as well as I did that if I could just get one decent shot at it, I would make good. We had only been married for three years, but she gave me all the support a man could reasonably ask of his wife and far more besides. It makes us appreciate what we have now all the more, because we have not forgotten those times when we had nothing.

Rosanne came into my life when I was seventeen. She is a year younger than me and we were both students at Solihull Technical College near Birmingham. Although we were not in any of the same classes, I had seen her around the college and she had really caught my eye. She looked bright, confident and strong and I knew that I wanted to meet her.

My chance came one morning while I was driving to college. I had passed my driving test and bought a second-hand Mini van. I saw her walking along the road, so I pulled over.

âHey, youâre going to the college, arenât you? Do you want a lift?â

She hopped straight into the car. She told me later that she only did that because she thought I was somebody else â a neighbour of hers â and that if she had realised it was a total stranger offering her a lift she would never have got in. As she has said since, âItâs funny how things happen in life, isnât it?â

It was only a short drive and we talked in general terms about this and that, but she made a major impression on me. We ran into each other more and more frequently at the college and before long we started going out together. It was a good relationship from the start and we made sure that we saw each other every day.

She was the youngest of three children from a loving family. She knew nothing about motor racing when I met her. Her brother watched the occasional Grand Prix on television, but didnât consider himself a fan.

I introduced her to karting and I think she could see immediately how important it was to me. What impressed me about her was how willing she was to muck in. Although I took her on some exciting nights out, we also had plenty of long nights in working on the kart and she became quite handy with the sandpaper and the plug spanner. She always used to stick around and help me and we developed a deep bond. Although karting was thrust upon her and she much preferred horse riding, she was behind me from the start and came to almost every race with my family.

Then came the Morecambe accident and she began to see the other side of racing. She was always nervous about watching me race â she is to this day â but Morecambe gave her a nasty shock. She was there when the priest gave me the last rites. She had never seen anything like that before, let alone when someone she cared for was the victim. It was her first experience of the dangers which motor sport can bring. It was a worrying time for her and, being fairly young at the time, she found that she was having to be very mature when dealing with a different side of life.

She could have tried to persuade me to stop after that, Iâm sure many girlfriends would have done, but she could see how much it mattered to me and I suppose she could also see that my competitive instinct would always need an outlet. If it wasnât karting it would have been something else.

As well as being highly competitive, I have always been very aggressive and very physical. As I matured as a racing driver I channelled these characteristics into positive aspects of my driving, but before I met Rosanne I used to like raising hell with my male friends.

I donât scare easily and I was never afraid to get into something with someone bigger than me. Having said that I was pretty large myself at that time. As we all know, beer is very fattening and by indulging my taste for it my weight shot up to almost 200lbs, which is a lot for a man of 5ft 10in. It was all pretty pointless, but when youâre a teenage male there is always pressure to be tough and to look after yourself. We used to dare each other to do daft things like jump off motor bikes at 30mph. That escapade landed one of my friends in hospital.

Rosanne was always a cut above all of that and I did not want her to get involved with that group of friends. In the early days of our relationship I would enjoy a civilised evening with her and then after I dropped her off I would go out again and hit the town with my friends. Gradually I changed, broadened my horizons and took more of an interest in the things which interested her. We would go on day trips in the car with a picnic, or visit stately homes and art galleries. She was really into horse riding, so I went along with her on rides. We enjoyed each otherâs company so much that it became second nature to me to want to do these things. After all it was only fair; she supported my karting and helped me work on the karts. We were happy and very much in love.