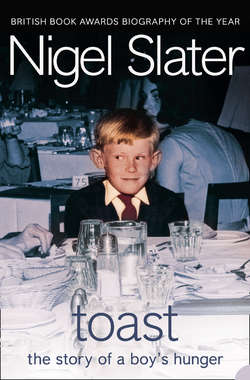

Читать книгу Toast: The Story of a Boy's Hunger - Nigel Slater - Страница 10

Sherry Trifle

ОглавлениеMy father wore old, rust-and-chocolate checked shirts and smelled of sweet briar tobacco and potting compost. A warm and twinkly-eyed man, the sort who would let his son snuggle up with him in an armchair and fall asleep in the folds of his shirt. ‘You’ll have to get off now, my leg’s gone to sleep,’ he would grumble, and turf me off on to the rug. He would pull silly faces at every opportunity, especially when there was a camera or other children around. Sometimes they would make me giggle, but other times, like when he pulled his monkey face, they scared me so much I used to get butterflies in my stomach.

His clothes were old and soft, which made me want to snuggle up to him even more. He hated wearing new. My father always wore old, heavy brogues and would don a tie even in his greenhouse. He read the Telegraph and Reader’s Digest. A crumpets-and-honey sort of a man with a tight little moustache. God, he had a temper though. Sometimes he would go off, ‘crack’, like a shotgun. Like when he once caught me going through my mother’s handbag, looking for barley sugars, or when my mother made a batch of twelve fairy cakes and I ate six in one go.

My father never went to church, but said his prayers nightly kneeling by his bed, his head resting in his hands. He rarely cursed, apart from calling people ‘silly buggers’. I remember he had a series of crushes on singers. First, it was Kathy Kirby, although he once said she was a ‘bit ritzy’, and then Petula Clark. Sometimes he would buy their records and play them on Sundays after I had listened to my one and only record – a scratched forty-five of Tommy Steele singing ‘Little White Bull’. The old man was inordinately fond of his collection of female vocals. You should have seen the tears the day Alma Cogan died.

The greenhouse was my father’s sanctuary. I was never sure whether it smelled of him or he smelled of it. In winter, before he went to bed, he would go out and light the old paraffin stove that kept his precious begonias and tomato plants alive. I remember the dark night the stove blew out and the frost got his begonias. He would spend hours down there. I once caught him in the greenhouse with his dick in his hand. He said he was just ‘going for a pee. It’s good for the plants.’ It was different, bigger than it looked in the bath and he seemed to be having a bit of a struggle getting it back into his trousers.

He had a bit of a thing about sherry trifle. That and his dreaded leftover turkey stew were the only two recipes he ever made. The turkey stew, a Boxing Day trauma for everyone concerned, varied from year to year, but the trifle had rules. He used ready-made Swiss rolls. The sort that come so tightly wrapped in cellophane you can never get them out without denting the sponge. They had to be filled with raspberry jam, never apricot because you couldn’t see the swirl of jam through the glass bowl the way you could with raspberry. There was much giggling over the sherry bottle. What is it about men and booze? They only cook twice a year but it always involves a bottle of something. Next, a tin of peaches with a little of their syrup. He was meticulous about soaking the sponge roll. First the sherry, then the syrup from the peaches tin. Then the jelly. To purists the idea of jelly in trifle is anathema. But to my father it was essential. If my father’s trifle was human it would be a clown. One of those with striped pants and a red nose. He would make bright yellow custard, Bird’s from a tin. This he smoothed over the jelly, taking an almost absurd amount of care not to let the custard run between the Swiss roll slices and the glass. A matter of honour no doubt.

Once it was cold, the custard was covered with whipped cream, glacé cherries and whole, blanched almonds. Never silver balls, which he thought common, or chocolate vermicelli, which he thought made it sickly. Just big fat almonds. He never toasted them, even though it would have made them taste better. In later years my stepmother was to suggest a sprinkling of multicoloured hundreds and thousands. She might as well have suggested changing his daily paper to the Mirror.

The entire Christmas stood or fell according to the noise the trifle made when the first massive, embossed spoon was lifted out. The resulting noise, a sort of squelch-fart, was like a message from God. A silent trifle was a bad omen. The louder the trifle parped, the better Christmas would be. Strangely, Dad’s sister felt the same way about jelly – making it stronger than usual just so it would make a noise that, even at her hundredth birthday tea, would make the old bird giggle.

You wouldn’t think a man who smoked sweet, scented tobacco, grew pink begonias and made softly-softly trifle could be scary. His tempers, his rages, his scoldings scared my mother, my brothers, the gardener, even the sweet milkman who occasionally got the order wrong. Once, when I had been caught not brushing my teeth before going to bed, his glare was so full of fire, his face so red and bloated, his hand raised so high that I pissed in my pyjamas, right there on the landing outside my bedroom. For all his soft shirts and cuddles and trifles I was absolutely terrified of him.