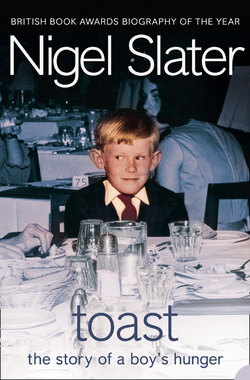

Читать книгу Toast - Nigel Slater - Страница 19

Sweets, Ices, Rock and Politics

ОглавлениеIt would be wrong to say we were wealthy. ‘Comfortably off’ might be nearer the mark, though without the implied smugness. There were tinned peaches and salmon on the shopping list but Mum still checked Percy Salt’s delivery scrupulously, running her finger down the list and ticking things off with a blue biro. Dad took cuttings and planted seeds – yellow snapdragons, nemesia the colour of boiled sweets, and those daisy-faced mesembryanthemums that only opened up when the sun shone – because it was cheaper than buying ready-grown bedding plants. Needless to say I had no more pocket money than any of my school friends.

I bought the odd book, annuals mostly, a few singles, ‘Can’t Buy Me Love’ or Dusty Springfield’s ‘I Only Want To Be With You’, and once, a stick insect, but most of my pocket money went on sweets. Buying sweets, chocolate, even ice cream was shot through with more politics than an eight-year-old should have had to contend with. Sweets could put a label round a child’s neck in much the same way as a particular choice of newspaper could to an adult. For a boy certain things were off-limits. Fry’s Chocolate Creams and Old English Spangles were considered adult territory; Love Hearts and Fab ice creams were for girls. Parma Violets were for old ladies and barley sugars were what your parents bought you for long car journeys. Cones filled with marshmallow and coated in chocolate were considered naff by pretty much everyone, though I secretly liked them, and no one over six would be seen dead with a flying saucer. Sherbet Fountains were supposed to be strictly girly material, an idea which even then I refused to buy into. Milky Ways were what parents bought for their kids, which gave them a sort of goody-goody note as did Jacob’s Orange Clubs. Selection boxes were what you were given at Christmas by the sort of people who weren’t relatives but who nevertheless you called Auntie.

We never really bought the penny chews that Mr Dixon had loose on the counter, though I did nick the odd liquorice chew, the ones that came in blue-and-white striped paper, when his back was turned. Dad’s favourites were Callard & Bowser’s Butterscotch, which came in thin packs like cigarettes, and Pascall’s oblong Fruit Bonbons with gooey centres. He also loved peanut brittle, which he ate by the barful. Mine were sweet cigarettes, which may not have given me lung cancer but made up for it with fillings. At Christmas, Dad bought himself metal trays of Brazil nut toffee with their own little hammer from Thorntons, while I got more cigarettes, this time made of chocolate wrapped in paper which went soggy when you put it in your mouth. Dad said they were expensive. Mum only ate sweeties that came in round tins, old-fashioned things like lemon drops and fruit pastilles with a faint dusting of icing sugar or those chewy blackcurrant gums that came in a flat white-and-purple rectangular tin.

Boys’ stuff, by which I mean gobstoppers, Milky Bars and Rolos, never really hit the spot for me. I spent most of my money on sweets that made your tongue sore: acid drops, sherbet lemons, chocolate limes and roll after roll of Refreshers. The price for which was mouth ulcers the size of shirt buttons, and on which I would put salt-and-vinegar crisps to see just how much pain I could stand.

Holidays meant sticks of rock, pink or humbug-striped with red letters running through it. I never ate mine till I had kept it for at least six months in the fruit bowl. By which time it had gone soft and chewy, like mint-flavoured toffee.

Your choice of ice cream depended more on who was buying. Mum would get me a cornet with a rectangle of vanilla ice cream wrapped in white paper. It was an ice fraught with danger. You had to peel off the paper and push the block of ice cream down into the cornet while at the same time licking every last, precious drop of vanilla from the paper. For herself, she would get a little block of ice cream wrapped in paper and two wafers, or a choc ice in foil. The best bit was the crackly chocolate which was so thin that it would shatter and fall off into her lap in jagged pieces. At the cinema or the pantomime we always had tubs, though my father invariably complained about the price and having to queue for so long that the second half had started before he got back to his seat.

My parents disapproved of the ice-cream van, with its pineapple Mivvis and belching smoke. I found the music – wobbly, like a music box running down – faintly sinister, like those clowns with white faces and pointed hats. I think my parents just thought it was common to queue. My favourite was the banana lolly or the chocolate one which tasted like weak cocoa. Mum drew the line at Mr Whippy cornets, which she considered beyond the pale, and 99s were simply vulgar. Heaven knows what she would have said if she had seen me on my way to school, biting off the end and sucking the soft, grainy ice cream through the bottom.