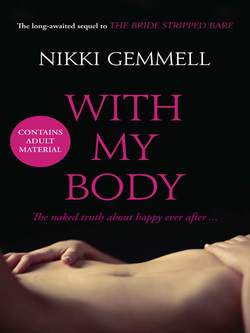

Читать книгу With My Body - Nikki Gemmell - Страница 27

Lesson 21

ОглавлениеElegant infamy

There is only one word for your naivety then. Magnificent. You have learnt no defences for the wiliness of grown-ups, their sophisticated ways, have never had to. You have lived your whole life in a bell jar of isolation.

Learning how to fashion a bridle out of a piece of rope and splint a broken bone when you’re stuck out bush, learning when to sense a coming rain; how to read a kookaburra’s laugh. Your tiny house is bereft of pictures on the wall, ornaments or books. A Bible on a side table is the only tome – unread – and the television is on every evening but it’s never the ABC with those posh, city voices. A Sydney Morning Herald has never crossed its threshold; classical music has never wafted out, it’s all Johnny Cash and Elvis, talkback and the Daily Telegraph. Your father is deeply suspicious of the world of the Big Smoke, of the well-born and the educated he rarely encounters, their social and intellectual confidence. The ease of them. It is only physically that the likes of him can ever compete, not that he wants to. His world is this valley.

Not a doll is in the house, not a frill or scrap of pink. Your treasured possessions are your Snoopy diary and your bike, Peddly, which becomes your horse as soon as you sit on its saddle, winging you every day to other worlds than this.

Your school, at Beddy Number One, is a single classroom. Twelve kids, aged five to eleven. Your teacher is like many of the women of the valley, soft-fleshed and ambitionless beyond snaring a husband and a motherly life; soon to be married and she’ll then leave teaching, which she has never liked, to devote herself to the job of wife. Her job is limbo land, the dead zone until something else.

‘Why do you want to do that, Miss? Wouldn’t you prefer to be with us?’ you ask, cheekily. ‘He’s a right old bush turkey the bloke you’re marrying, that’s what my daddy says. Beyond his use-by date.’

‘Get out.’

Which is what you want, of course. Almost every day you are released from the tiny classroom. She has given up on you, doesn’t know what to make of your blunt voice, your absence of understanding what’s wrong and right, your wildness and your wilfulness, your constant gazing out the window, champing at the bit.

Wanting out. Licked by sun and wind. Now. Not a part of this. Every day.

She doesn’t see your knottedness, your enormous heart, primed for love – to give and receive it. Doesn’t know what to make of your vast alone that she senses has no desire for her world, for everything she represents. Because you perceive in her, even then, some kind of an erasure, that there is no audacious sense of who she really is. She wants to disappear into someone else’s life; she desires it more than anything else. That, to you, is bizarre. The one message your teacher imparts to you, upon the dewy, blinkered brink of her shiny new existence, is that women who are thinkers do not get married.

Then there’s Anne. Waiting in the wings to take over your life.