Читать книгу Antonia Mercé, "LaArgentina" - Ninotchka Bennahum - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление| ARGENTINA AND SPANISH MODERNISM | 1 |

Antonia Rosa Mercé y Luque (1888–1936), or “La Argentina, as she was generally known, was the most celebrated Spanish dancer of the early twentieth century. Adopting as her professional name the country of her birth, Argentina was the only female member of Madrid’s avant-garde to dance. In 1890, at the age of two, she was taken to Spain by her parents, dancers on tour. Her mother was a première danseuse at Madrid’s Teatro Real, and her father was its principal ballet master. She was trained by him from age four, joined the company at age nine, and was appointed première danseuse at age eleven. In 1910, after a long trip through southern Spain with her mother, where Argentina began to study flamenco dance and Gypsy life with Sevillian Gypsy women, Argentina went to live in France where she would make her home, her career, and her life. Argentina’s modernism was shaped by three colossal forces: Paris and its avant-garde art world, Spain’s Gypsy past, and European Romantic neoprimitivism.

Paris in 1910 was the center of the modern art world with a European and American émigré population of artists. Georges Clemenceau, president of France, commented that the future rests always with the avant-garde. The cubist legacy of Paul Cézanne and the coloristic ideas of Henri Matisse had radicalized young artists of all genres into believing that the old-fashioned academy no longer held the answer—the formula—to making “good” art; high art. One could actually be self-taught, and young artists, like Salvador Dalí, were discovering that their own personal ideas—highly influenced by Sigmund Freud’s theories of the unconscious mind in the dream state—could provide the modus operandi and inspiration for an entire painting, or an entire ballet.

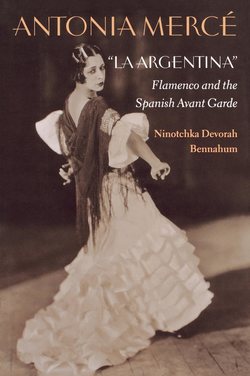

A young Argentina posing in Spanish dress, 1920s, Paris.

From Paris and from her world tours, Argentina’s lifelong correspondence with the Spanish vanguard—Manuel de Falla, Federico Garcia Lorca, Enrique Granados, Néstor de la Torre, Joaquín Nín, and Gregorio Martínez Sierra and María Sierra—establishes her importance to modernist Spanish art, both in Paris and worldwide, from the second decade of the twentieth century until her death on 18 July 1936. Alongside and in collaboration with such outstanding artists, Argentina also transformed the Spanish arts of the period. Her collaborations with numerous Spanish composers, painters, writers, and poets secure her importance as an artistic force in Spanish cultural history.1

Argentina’s career coincided with a particularly volatile moment in Spain’s history. With radical syndicalism and incipient revolution on the horizon, women were politically restrained by Spanish law and social mores, limited in movement, and in their right to express themselves as they desired. Paris, by comparison, was a serene city in which to work, more liberating for a woman living and working alone, and Argentina found a home there in 1921. It was in Paris that Gertrude Stein and her brothers Leo and Michael would provide a salon and showcase for Matisse, Picasso, and many other modernists, mainly Spanish and French, who were also interested in theatrical design. Although industrially polluted and heavily populated, Paris was a beautiful city that provided a certain anonymity. And, by virtue of its artists, its exiled and émigré populations from World War I, its café culture, its theatrical traditions, and its audiences, it was appealing to a young artist seeking a place in which to realize herself.

Flamenco as Modern Art

For Spaniards, flocking from the conservative and Catholic atmosphere of turn-of-the-century Madrid, Paris became a haven for the exploration of their radical ideas. In Paris, their dismissal of historical portraiture and their adoption of an austerely Spanish cubism would speak not only of and to Spaniards, but become, in the hands of a Picasso or an Argentina, a universal language of modern art. Who best to describe the Spanish aesthetic credo but its greatest supporter, the American aesthetician Gertrude Stein, who lived in Paris and encouraged the latest trends in the arts?

Stein believed that the “new” art of composition that was created in Paris arose solely from the exodus of Spanish artists—Julio Gonzalez, Picasso’s teacher, Pablo Picasso, Juan Grís, and Joan Miró—to France in the early twentieth century. For Stein, the “instinctive tragedy” and the stark compositions of synthetic cubists like Picasso and Grís was a Spanish phenomenon. “Americans can understand Spaniards,” wrote Stein in her autobiography of 1925. And “cubism” as created and executed by Spaniards “is a purely Spanish conception; only Spaniards can be cubists.”2 That commentary may be a bit limited, but as the main supporter and collector of early cubist work, Stein was relating not only to the “insistent iconography”—the object as subject—of a painting, but also to the primary feeling of the composition. Stein once referred to Picasso’s “passion and sexuality, directed wholly toward his painting.” By this, she meant his Spanish persona and his Spanish-informed genius.3 Further, the words “insistent” and “passionate” also reveal a violent and angry temperament—the Spanish persona about which Stein wrote. A parallel will be drawn between the intensity of Picasso’s brushstrokes and the fury associated with flamenco footwork as choreographed and performed by La Argentina in her most mature works of cubist design.

When Argentina came to dance on the French stage; she could not help being influenced by Picasso and his fellow cubist, Georges Braque. At the 1925 Spanish Pavilion for the Exposition des Arts Décoratifs, where she danced, she was bound to have encountered Juan Grís, a fellow Madrileño whose painting The Green Cloth hung in the Nouveau pavilion. Indeed, this very pavilion was designed by Le Corbusier, an architect whose work might have reminded her of the Catalonian structures built by Antonio Gaudi (1852–1926). Argentina would become what Stein felt Grís was: “A Spaniard who combines perfection with transubstantiation,” a painter whose “very great attraction and love for French culture” made him a compelling artist.4

Although Argentina missed the 1905, 1907, and 1909 Salon des Indépendants and Salon d’Automne, she was most likely captivated by Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), his still lifes with guitars (1907–14), and Grís’s Flowers (1914). She was a discriminating woman, a woman of taste, who saw everything, inhaled everything, and then used what she liked as material for her own work. Inspired by both French and Spanish design, as she was by Diaghilev’s, Nijinsky’s, and Massine’s theater, Argentina broke with traditional Spanish ballet. Although she was the soloist, she was no longer always at the center of the composition: at times, her set designer’s looming scenery would be tipping toward the stage, absorbing the dancer’s violent footwork just as Picasso’s decomposed compositions flattened his figures through violent brush strokes, removing hieratic and hierarchic significance from the composition and imposing a more evenly distributed (or disruptive) sense of disproportion, disunity, and disorganization. Second, these Spanish cubists’ break with what Stein called “the evil nineteenth century” breathed a neoprimitivist aesthetic. For example, Picasso’s use of a pre-Roman Iberian mask for his portrait of Gertrude Stein and his use of Yoruba masks for Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, although a cultural theft on his part, might well have provided Argentina with the idea of looking into Gypsy culture, an oriental culture that lived in hiding within Spain itself.

Just as Picasso would use the Iberian mask for Stein’s face to re-invent his subject, objectifying her so that he could capture her colossal will and extraordinary single-mindedness, Argentina would use Gypsy rhythm as the sole signifier and accompaniment, the principal choreographic and musical agent throughout an entire ballet (for example, La vida breve). The idea of rhythm for Argentina—and for the Gypsies—like the unspecific look of the mask for Picasso, allowed the aesthetic of the ballet to become more important than the dancing bodies themselves. As Argentina’s choreography and taste for scenic design improved and matured, the semiotics of her late ballets like Sonatina and El contrabandista not only subsumed the composition; they became its genesis. Just as Picasso used—and stole—the African mask from its original context, translating its masklike exterior into a new formal vocabulary which he then reconfigured, out of Argentina’s use of the flamenco rhythm, accompanied by Manuel de Falla’s use of ancient Jewish liturgical chant, the saeta antigua, would emerge a modern, cubist composition in which bodies were no longer bodies but the objects of sound.

Argentina and Les Ballets Espagnols in Scene 1 from Triana, Opéra-Comique, 27 May 1929.

Like Picasso, Argentina began to draw on the decorative aspects of Gypsy and Spanish peasant culture, exploring color and design motifs and using them as theatrical through-lines. Argentina’s interest in the local as an expression of a homogeneous, self-contained people became the onstage cuadro, or group, a reflection of the isolated Gypsy clans.5 For Argentina, the Gypsies’ utterly private, tribal existence provided a utopia, the perfect ethnographic laboratory. The artist, she felt, could discover the essential “tools” of her movement language in her own land; in the authentic, unobtrusive, objective voice of Andalusian culture. It was for her a completely subjective universe of song and dance that could be modified and recomposed through the body of a part Andalusian, part Castilian performer. It was, finally, a Romantic vision of Spain transfigured into modern artistic expression.

Argentina in a solo performance of La Corrida, at London’s Aldwych Theatre, 15 June 1936.

Argentina’s productions that were collaborations offered modernist visions of a multinational Spain. Her ballets Triana and Juerga, for example, embraced both Andalusian Gypsy and Spanish folk culture.6 Her professional relationship with the Spanish modernist composer Manuel de Falla, especially, became the catalyst for two other lyric dance-dramas, both prime examples of her modernism: El amor brujo and La vida breve. The New York Times critic John Martin wrote that both works demonstrated her ability “to capture the aliveness of the Spanish body and hold it in the bounds of form.”7

In 1925, she created the full-length story-ballet around the old Andalusian Gypsy legend “El amor brujo” (Love, the sorcerer). For it, she developed new dimensions for mise-en-scène using Spanish themes, as she reworked Spanish dance. She took the Spanish classical dance technique and, experimenting with Gypsy flamenco rhythms and stories, realized a new and succinct dance vocabulary that became a performed national language for the next decade on the stages of Europe and the Americas. Her fusion of Gypsy and Spanish classical traditions became the basis of her working vocabulary, one she used to train her company of dancers, who themselves were fine flamenco artists, often of Gypsy ancestry. Argentina produced the first modernist dance-dramas created by a Spanish choreographer. Working only with Spanish collaborators, Argentina had developed an art form that was genuinely national. She had rediscovered the narrative potential of Spanish movements and music and made them symbolic of Spain’s complex history, recognizing its peoples, cultures, and physiognomy.

Scene 1 from the ballet Juerga, 10 June 1929, full company, music by Julian Bautista, sets and costumes by Fontanals, premiered at the Théâtre Marigny.

La Escuela Bolera

Argentina believed that the tradition in which she had first been trained must form the basis—the model—for her vision. Argentina’s aim was to create a new form of narrative and wholly Spanish dance-theater, fully orchestrated and costumed for the proscenium stage. Her “uniqueness,” as the French author Anatole France described her meticulous approach to Spanish dance, was academically classical in its use of ballet-inspired boleros and jotas—dances of the Teatro Real de Madrid. Argentina’s early repertory, from 1910 to 1915, drew significantly upon the bolero tradition. The bolero—as a dance and a genre based on a combination of indigenous Spanish dances by eighteenth-century dance masters—was used as both a choreographic tool and a dance style. Argentina, however, used the bolero as a solo and not as the couple dance that had been modified in the mid-eighteenth century from the seguidilla bolera (and from the 3/4-time seguidillas manchegas before that).8 It allowed her to demonstrate extremely technical, classical technique, while accompanying herself with castanets and quick changes of direction.

In using the step and the style of the escuela bolera, Argentina paid tribute to the artistry of her parents, especially her father, while developing a modern sensibility on an old-fashioned form. The escuela bolera was a synthesis of early nineteenth-century bolero, other Spanish dances, and elements of French ballet that came together in Seville during the Napoleonic era.9 Argentina changed the bolero through the incorporation of Gypsy flamenco footwork and armwork. Together, light bolero jumps and turns combined with earth-centered Gypsy dance traveled a dual-national but Spanish dance from the eighteenth to the twentieth century. In its newly transfigured form (1925–36), Argentina’s vision of the bolero would become a reinvented Spanish tradition that could survive both the modernist artists’ abhorrence of the past (that is, the ephemeral qualities of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Romanticism) and the cubo-futurists’ embrace of twentieth-century mechanization (that is, linearity, angularity, and the aesthetic of the ugly). Instead of allowing the sylph to disappear entirely from the stage—turned into an earth-driven Gypsy flamenca—Argentina, in combining the bolero and the bulerías (Andalusian song and dance), folded a more ethereal vision of dama, perhaps preindustrial, into the cosmopolitan working woman.

Nevertheless, Argentina’s dance was also motivated by an ethnographic interest in Spain, her adopted homeland; this interest took the form of an assiduous exploration of the dances of Castile, Aragón, Navarre, Valencia, Galicia, and Andalusia. Her multiethnic vision of Spanish ballet was recognized by the Russo-French critic André Levinson as early as 1923. Levinson’s critiques of her Parisian performances, as well as his 1928 monograph on the artist, helped launch her to fame. In this later work, Levinson explained her transformation of the Spanish dance: “Argentina,” he said, “was transposing the themes of Spanish folklore, the native dances which are the first rude stammer of primitive instinct, into style. She understood perfectly the two-fold nature of that dance—scene and spirit—that makes it so fascinating. Thanks to her, Spanish dancing has now entered a new phase and risen to hitherto unattained heights of sublimation.”10

Argentina on tour in Holland, 3 April 1935, press conference.

La Prima Modernista

Argentina had first achieved broad recognition as a soloist in 1916, touring Spain, North and South America, and northern Europe with her guitarist and family friend Salvador Ballesteros and her pianist, Carmencita Pérez. By 1923, Argentina’s name was uttered in the same breath as that of the great French tragedienne Sarah Bernhardt, the American dancers Isadora Duncan and Loïe Fuller, the Spanish film and stage actress Raquel Meller, and the Spanish “art” dancer Tórtola Valencia. In the company of these women, Argentina performed in Paris, Moscow, New York, London, Madrid, Seville, Tunis, Tokyo, Shanghai, The Hague, and Mexico City. She would return to her birthplace only on short tours.

Like Tórtola Valencia and many other female soloists of the 1920s, Argentina also incorporated an exotic approach to the Spanish dance, juxtaposing the escuela bolera, the bolero school, which had its origins in ballet, with flamenco puro, or pure flamenco. In order to realize this, Argentina became an ethnographer, traveling Spain’s forty-nine provinces with her pianist, who would transpose local melodies to be used later in full orchestral compositions. Argentina went in search of regional sounds, colors, and stories, which she used to people her ballets, clothe her characters, and decorate her scenes. In doing so, she brought to the stage her vision of the immensely varied Spanish dance. She breathed life into centuries-old Gypsy dances, while paying close attention to the rituals and customs found in Gypsy culture.11 Argentina’s interest in authentic sources paralleled that of the Russian-born Ballets Russes choreographer Michel Fokine, and it anticipated the 1922 Concurso de cante jondo—a “deep song” singing competition organized by Spanish composer Manuel de Falla and poet Federico Garcia Lorca.12 It was part of an effort to resuscitate the legacy of flamenco music and song.

Argentina in a solo performance of Tango Andalou, music by Ballesteros, at Brooklyn’s Academy of Music, 3 June 1935.

For Argentina, Falla and Garcia Lorca provided a neonationalist design for the study and canonization of flamenco music and verse. But it was Argentina who began as early as 1905—her first adult trip to Andalusia—to study and then use flamenco’s other elements: its fierce zapateado (footwork) and its intensely contemplative, sensually focused individualism of the bailaor (dancer). Flamenco was intended to complete the Spanish neonationalist philosophers’, Felipe Pedrell and Adolfo Salazar’s, mission: to help “save” Gypsy culture from commercialization and industrialization. Like most dancers, Argentina believed that to preserve a culture was to embody it. Yet Argentina was to go one step further than such figures as Pedrell, García Lorca, and Falla. She was to use the flamenco tree, its cantes chicos y jondos (light and heavy songs), to modernize Spanish ballet, thus helping to elucidate Spanish culture.

Falla recognized in Argentina’s work the visual realization of his scores. “With so much excitement,” he wrote, “did I read what you told me about the latest of El amor brujo, which owes so much to your splendid art. I can’t imagine it any more without your work! I assure you of that! And with your work it will have to be.”13 And García Lorca echoed his great friend in his dedication of three ballads from Poema del cante jondo to the artist of whom he was a “fervent admirer.”14 “This is where I wanted to express the very personal art of La Argentina, the creator, inventor, indigenous and universal,” he wrote.15

After 1915, Argentina’s modernist approach to Spanish theater—exoticism as neoprimitivism in the service of the neonational—appeared with greater frequency. And Argentina’s solos became longer, with fewer danced each night, as each dance began to contain a more sophisticated narrative. Slowly, Argentina began to mount full-evening ballets with libretti and orchestration. By 1925, she had created El amor brujo, thus realizing her personal aesthetic.

Argentina posing with Filipino folk dancers after her own performance at a dance festival in Manila. From the Filipino dancers Argentina learned the steps and music for La Cariñosa, which she made into a solo ballet with costumes sewn by the Callots Soeurs.

Argentina had also absorbed the local traditions of other countries in which she toured. For example, in the Philippines she learned a popular folk dance, la cariñosa, performed in layers of silk cloth (color plate 6). She learned the dance’s rhythms and repetitions and copied the costume. She lengthened and straightened the dress into a columnar cascade of straight, Art Deco lines, however, and added a fan, a typically Spanish prop. Argentina’s La cariñosa, became one of her most famous and frequently performed solo dances.16

French Orientalism

Interested in the new Paris fashions—Jean Patou’s gowns, Maximilian’s furs, and French haute couture designs—Argentina achieved a kind of fashion synthesis, an idiosyncratic couture for her production, with folk motifs, usually two-dimensional, representational drawings of agrarian scenes, and Néstor de la Torre’s cubist fracture of Gypsy tabernas (taverns) and grottos. Between the resulting curved and straightened lines she danced, using her complex choreographies to unite sight, sound, and effect.

Argentina’s expression of these cultures became ceaseless, echoing what Théophile Gautier termed “les couleurs locales.” The neoprimitivist aesthetic of El amor brujo, Juerga, and Triana, in particular, which were examples of a neofolk vision, sewn onto costumes and stamped out in taconeo, or heelwork, give evidence of Argentina’s innovation—her ability to “reinvent traditions,” as Eric Hobsbawm has described such ethnographic art.17

Several other important sources fueled Argentina’s representation of the Spanish folk: the French Romanticism that began in the 1840s in painting and literature, and the ethnographic modernism that had been associated with the Ballets Russes’s productions, such as Petrouchka and Le Sacre du printemps. French interest in Spain had awakened during the French invasion and occupation of the country during the Napoleonic period. The French regarded Spain as “the gateway to the Orient.”18

At that time, the Spanish saw themselves as separate from the rest of Europe. The southern regions of Spain—what Garcia Lorca referred to as the three-cornered hat of Seville, Granada, and Cordoba—had been ruled by moderate and fundamentalist Islamic caliphs from North Africa during the Middle Ages from 711 to the last in Granada, in 1492. The Spanish Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella, reconquered a new, all-Catholic, white Spain. Nevertheless, the vast architectural and cultural influence of the eight-hundred-year presence of the Moors and Jews—of Mozarabic culture—dominates the Spanish landscape even into the twentieth century. (The Jews, who entered Spain as Roman slaves and merchants in 450 B.C.E., and the Moors inscribed an oriental socioeconomic and political outlook on Andalusia—a non-Western approach to social behavior and artistic creation that, though long gone, still continues to influence southern Spain today.

Argentina on her third world tour to Asia, 1930.

The philosopher Miguel de Unamuno explained Spain’s self-identification in this light. “We must Africanize ourselves ancientwise,” he said, “or we must ancientize ourselves Africanwise.”19 This self-orientalism explains something of the Spanish character: sensual, sometimes cruel, and self-deprecating, the conquered and the conqueror at once; the victim of her own bloodlust, like that in the bullfight. In La corrida, Argentina’s signature piece, she reflected Unamuno’s words.

France’s romanticized view of Spain persisted until the Spanish civil war (1936–39). The French adoption of the mystical and mysterious nature of Spain’s Moorish heritage was paralleled by the vogue for Spanish dancers and singers on the Paris music hall stage. “Spanish” acts of dubious authenticity were popular. Beyond that, they were associated, as in the case of Carolina (“La Belle”) Otero, with dancers of equally questionable morals. The result projected an image of Spain divorced from the rest of Europe. The Spanish specialty acts on the music hall stages presented an exotic, erotic, and culturally separate “other” Their representations of Andalusian Gypsies, much like that of nineteenth-century American minstrel shows, portrayed a lewd and lascivious population. In the case of the southern Spanish Gypsies, they were situated within Spain almost by chance. Although Gypsies had wandered into Europe between the ninth and the fourteenth centuries, exiled from Rajasthan by Muslim invaders, they are considered outsiders to this day, just like the Moors and the Jews. Gypsy customs—their dancing, singing, clothing—were considered strange and inferior to those of the white European, even after their incorporation into European tradition over the centuries, with their forced conversion to Catholicism from the early fifteenth to the early nineteenth centuries.

Argentina on her fifth world tour visiting the Sphinx in Egypt with a guide, 1934

French painter Henri Matisse’s large triptychs of seated North African women surrounded by deep purples and the light blue of a highly sensual, luscious, and romanticized Mediterranean, for instance, serve as perfect examples of the French fascination with Moorish culture along the Iberian Peninsula. Their heads bowed down in quiet contemplation, the women appear almost invisible, hidden in the shadows of rounded doorways or seated subserviently, awaiting someone’s entrance. So silent are Matisse’s views, one can hear the wind. Matisse’s round skies and flat figures would become backdrops for Argentina’s ballets.

Russian Orientalism

A major influence on Argentina’s choreographic composition, perhaps the most significant, was the Ballets Russes, the Russian-trained modernist ballet company first brought to Paris by impresario Serge Diaghilev in 1909. The Ballets Russes productions were the result of close collaborations among musicians, poets, painters, designers, and dancers. There is no question that Argentina saw a number of their productions from her time in the French music halls to the time she formed her own company. It was evident in the fusionist ideal underlying Argentina’s mature work, in her close and collaborative relationship with artists like Néstor and Ernesto Halffter and others of the so-called Spanish New School. Argentina’s friend and mentor, Manuel de Falla, introduced her to the idea of lifetime collaboration. Falla had composed Le Tricorne for Diaghilev in 1915 as the Ballets Russes sat out the First World War in non-aligned Spain, and working with Diaghilev, he might have thought it the best means of creating dance-theater: musical, libretto, scene design, and choreographic elements produced by different people, and brought together as an integrated composite spectacle.

The meticulous professionalism of her productions, whether small-scale or large, proved that her desire was to create a Spanish form of modernist dance-theater much like that created by Diaghilev. With her own company, Les Ballets Espagnols, Argentina demonstrated her allegiance to the broad aesthetic of the Ballets Russes: the collaboration of Fokine and Stravinsky in Petrouchka (1911), Nijinsky and Stravinsky in Le Sacre du printemps (1913), Falla and Massine in Le Tricorne (1919), and Stravinsky and Bronislava Nijinska in Les Noces (1923).

Moreover, much like the “primitive” people who populate Nijinsky’s Le Sacre du printemps, as well as the populist acrobats who catch the eye in Fokine’s Petrushka, Argentina’s flamenco cuadros signify her desire to return to popular roots, much as Diaghilev had.20 Might she have seen Sacre? Argentina was in Paris in 1911 when it was first shown. It is most likely that she saw it, and that it had a significant effect on her choreographic structure. Perhaps it was the reason she wanted to perform in Russia; to learn from the Maryinsky dancers and to experience Theater Street for herself.21

Like Fokine before her, Argentina was fully aware of the important play between soloist and ballet company. It is this tension between bailaora and caudro that heightens the isolation of the flamenco figure dancing alone in soleá (a melancholic Andalusian song and dance). Argentina’s lifelong, and most applauded, solos remained the musicless Seguidillas, performed to the accompaniment of her own hands with castanets, and La corrida, performed to Valverde’s music or to her castanets alone.22 La corrida was, in fact, her first choreography for the Moulin Rouge. In it, she reenacted the cruelty and show of the bullfight and its arena, the Corrida.

Argentina’s most important debt to Fokine was the romanticization of the folkloric for use as choreographic material. The crowd became the community just as the corps de ballet had symbolized the onstage family. Like Fokine, Argentina extracted the soloist from the corps, thus emphasizing the body and, later, integrating the solo divertissement within the dances performed en masse. For example, Fokine’s carnival scene in Petrouchka, replete with ordinary street-fair activity—acrobats, magical shows, and food displays—may have influenced Argentina’s fishmarket scene in La malagueña (1932), which bustled with regional dances and various other transactions. Her choreography broke with the routine of traditionally peaceful Spanish ballet displays of eighteenth-century majas (elegant young women).23 Instead, Argentina created background movement and noise and the seemingly ordinary exchange of money at market time, acted out through dance and song.

For her 1925 version of El amor brujo, Argentina seemingly was influenced by Nijinsky’s vision of Russia’s past in Sacre. Like him, she relied on pantomimed magic to tell her tale of incantation and love, reconstructing the Gypsy tradition of sorcery. In it, Argentina danced like a bruja (witch), around a fire built on the earthen floor of a white-washed pueblo in Cádiz. The Gypsy women gathered around the fire, whispering magical tales during the “ritual dance of fire.” The result mirrored the virgin sacrifice in Sacre.

Hispanic Modernism

Folk culture, then, which might be molded and reconstructed, became one of the most significant and useful tools of Fokine, Nijinsky—and Argentina—to express the modernism of the moment. It is seen, for example, both in Nijinsky’s L’Après-Midi d’un faun and in Argentina’s Cuadro flamenco, also known as En el corazón de Sevilla (1928). For Argentina, “hispanism as modernism,” as the French artist Desbarolles termed it in 1851, was a modus vivendi, as well as the material through which she, like her Russian models, discovered her voice.24

With the formation of Les Ballets Espagnols in 1928, Argentina became known as the Flamenco Pavlova, a self-produced female artist. She was accompanied by fifty-member orchestras, often conducted by the Spanish maestro Enrique Fernández Arbós, and she was partnered by Vicente Escudero and the great French mime Georges Wague. When she died on 18 July 1936, Argentina’s obituary appeared on the front page of newspapers around the world. From this recognition, it is clear that her death signaled the end of an era of great Spanish dance-theater. Today, a faint echo of her meticulous attention to detail, her fierce musicality, enormous charisma, and ceaseless devotion to the stage survives in the filmic collaborations of Carlos Saura and Antonio Gades, the dance-dramas of Mario Maya, and the flamenco-ballets of Manolo Marín. Curiously, no other Spanish woman has rivaled Argentina as a performer, director, and choreographer. Yet few cultural historians have remembered her. How could an individual, so famous in her own time, be so little remembered by the country that thought of her as “the soul of Spain,” as its cultural ambassadress?25 Perhaps the politically tense decades, discussed in chapter 6, both before and after her death in 1936 help explain why Argentina remains a forgotten figure in Spanish cultural history.

The Spanish Civil War

In the words of the prime minister of Britain, Winston Churchill, “the gathering storm of fascism” was building to the south. In 1933, with the rise of Hitler, it would change Europe forever; in 1936, with the Spanish civil war, the essence of Spanish life and culture. Argentina, Lorca, Falla, and the Spanish New School writers and composers were about to lose their artistic homeland. Under Franco, Spain would return to the repressive, fascist state it had been during the Inquisition (1478–1834). For many, their lives would be destroyed in the wake of the 1936 invasion by General Francisco Franco’s thousands of troops. The Spanish Falange political movement would come with him from Morocco, through southern Spain, in just three days. It would finally enter Barcelona on 18 July 1936—the day that Argentina died.

The Spanish modern artistic world, with whom Argentina had gravitated to Paris, would soon be dispersed around the world, in a state of permanent exile. Lorca would be killed by the peasant Falange of Granada shortly after the outbreak of the Spanish civil war.26 Despite an American presence in the form of the idealistic volunteer Abraham Lincoln Brigade (where authors George Orwell and Ernest Hemingway had joined in the democratic resistance movement), the Spanish Republic crumbled under the force of German air support and Franco’s troops, city after city falling into the hands of the dictator.

Argentina, like most Spaniards, had foreseen the war. From the summer of 1928 and for eight years until her death in 1936, Argentina wrote to her best friend, the pianist Joaquín Nín (brother of the author Anais), about her great political fears and personal sadness at the “destruction of [my] beautiful country by conservative forces.”27 And Nín replied, “Spain is still sick. Let’s hope that there is a remedy for this crisis and that in the end reason prevails…. So far, there has been little progress. The peseta is anemic. We are managing and that is not bad.”28 The Catalan capital would be overtaken in less than one year. Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937), the first picture he painted since 1935, became a symbol of the bombing. Guernica, a pictorial, political chronicle in black, white, and gray of the horrors of war in the Spanish village of Guernica, bore witness to the outrage which Goya had recorded in 1805. (It now hangs in the Reiña Sophia in Madrid, testifying to the ghosts of that war, and all war—the victims and their silence.) While the Guernica would become an international icon, La Argentina would fade away, until little of her art or memory remained. Few in 1936 would have imagined such a fate for a woman at the peak of her international fame and artistry, with such influence on the artists and culture of her time. Yet, she was forgotten. How this came to be is one of the mysteries of our century. How it happened partly reflects the ephemeral nature of dance, a dynamic art form rooted in the now that defies static attempts at preservation.

By 1939, Franco had killed forty thousand of his dissident countrymen, and the killings would continue there until 1940. Thousands fled to Latin America and to parts of northern Europe, unable to return to Spain for fear of imprisonment, torture, death. Franco’s puritanical, fascist press went to work quickly to minimize or even erase anything he considered threatening to his new regime. A repressive attitude toward women was instituted; thus Argentina, the model of independence and entrepreneurship, the woman of grace, sensuality, subtlety, and popularity, was wiped from the history books (just as the short-lived Spanish Democracy movement was quickly replaced by military rule). By 1975, when Franco died, her reputation had all but evaporated. Spain was desperate to enter the European Economic Community, to become a country that could compete with others and do business with the United States. Like the Escorial, Alfonso XIII’s royal palace, Argentina’s magical portraits of Spain have been ignored, made hollow, translucent, imaginary.

Eight years before, in 1931, King Alfonso, who had so loved the dancing of Argentina, was forced to flee Spain. Primo de Rivera’s anti-monarchical government had successfully, although temporarily, rendered the monarchy powerless. At the same time that Spain was in political transition, Argentina was awarded the French Legion of Honor for her cultural service in representation of her country. One year later, in 1932, following a performance in Madrid, she received the Isabel la Católica, presented to her by the president of the Council of the Second Spanish Republic, Mañuel Azaña.

At the end of 1931, a fond admirer of Argentina’s, the renowned prima ballerina Anna Pavlova, died.29 Pavlova’s death had followed the deaths of Sarah Bernhardt and Isadora Duncan in 1927, and of Loïe Fuller in 1928. By 1929, Diaghilev died in Venice and the Ballets Russes dancers dispersed around the world. One might argue that the loss to Paris of the Russian company was filled by Argentina’s Les Ballets Espagnols. Argentina, as an impresaria, inherited from Diaghilev the position of director of the largest ballet company in Paris. And like the Ballets Russes, Les Ballets Espagnols satisfied the French public as a popular foreign company whose stage designs and dancers appeared exotic and oriental—Indo-European Gypsy and southeast Asian, at once—yet grounded in Spanish ballet technique.

Legacy

Franco’s suppression of the memory and work of Spanish artists associated with the Generations of 1898 and 1927 (that is, any artist involved in the flowering of Spanish modernism) helps to contextualize Argentina’s important association with Spain’s literati prior to 1936. To understand why her work and importance to Spanish culture was obfuscated after the Spanish civil war, one must understand that she was excluded from the history books.30 The Generations of 1898 and 1927, however, whose members included such famous literary figures as Miguel de Unamuno, Ortega y Gasset, Jacinto Benavente, Pío Baroja, Federico Garcia Lorca, María Sierra, and Ramón del Valle Inclán, embraced the same Spanish and Gypsy folk culture that so interested Argentina. The Generation of ’27, having lived through World War I and the Russian Revolution, was far more radical than the Generation of’ 98 who had been fighting mostly against the restraints imposed by the Spanish Catholic clergy. The Generation of ’27 aimed their pens mostly at the monarchy in an attempt to build a parliamentary, electoral government out of the medieval, centralized bureacracy of the Cortes system of the Escorial. Argentina’s performance was symbolic of the nationalist energy of the New School generation; her work further integrated their ideology into Parisian modern art circles. These writers, many of whom wrote reviews, essays, and prose on Spanish dance, used Argentina’s performances as material for their musings. Benavente, Ortega y Gasset, and Valle Inclán, in particular, praised the neonationalist aesthetic of the young Argentina. And in the midst of overwhelming political strife, using her as his muse, Ortega y Gasset wrote his 1922 “Meditations on the Spanish Dance.”

As in the case of Garcia Lorca, one might argue that Argentina’s legacy as a Spanish neoprimitivist, utterly devoted to finding a voice for the Spanish Gypsy, was erased by the neonationalist governmental “reforms” of Spain’s dictator, General Francisco Franco (ruled 1939–75). In his biography Franco, Paul Preston argues that Franco’s effort to root out modernists, liberals, and monarchists—anyone associated with either free thinking or the established church and crown—was jailed or killed during the Spanish civil war. In addition, we know from the records of the sección femenina in Madrid, Franco’s all-female folk dance academy, organized to teach the representative dances of Spain to women, that dance was sanitized by him and used as a form of political propaganda—a fascist-sponsored leisure activity for girls.31 Franco’s attempt to reconstruct a society divorced from its interwar period was successful, of course. The Spanish literati, composers, and visual artists who chose to represent Spain individualistically instead of nationalistically had disappeared by Franco’s death in 1975. It is necessary to place Argentina within that political and social context, as it is impossible to isolate her from the times in which she worked.

Unlike a poet, a composer, or a writer, a dancer loses her place in the minds of her public when her physical body is no longer present. Words reside in pure form as do musical notes, but Argentina’s dancing—like that of Vaslav Nijinsky’s or Anna Pavlova’s—barely captured on a three-and-one-half-minute film sequence, could not hold popular attention for long after her death. This is one reason why she has received so little attention, but there are others.

Although she was loyal to the left, many of Argentina’s friends and patrons came from the upper class, some of whom were not leftists at all, and the Spanish monarchy and upper class were soon obliterated by Franco. Without them, without performance on film, and without the two intellegentsias, the Generations of ’98 and ’27, how could a star of the dance world be remembered? Who was left to write about her? World War II was then fought throughout Europe from 1939 to 1945, and rebuilding war-torn Europe continued until the 1950s. Moreover, as Argentina had died prematurely, she had never taught or opened an academy in Madrid where she could pass on her knowledge and creative principles to the next generation.

Argentina in the Excelsior Restaurant, Madrid, with the Spanish literary vanguard. Argentina seated all the way at the end of the table (center) in the back of the photograph. Banquet dinner, 1928. Members of the intellectual vanguard include Jacinto Benavente, Enrique Fernandez Arbós, Rosario Pino, Ramon del Valle-Inclán, Alvarez Quintero, Ignacio Zuloaga, Mariano Benlliure, and Manuel Machado.

Still, for Spain to have forgotten such a star remains puzzling. Argentina, so bright in her day, is like a candle that burned out as Franco’s forces, armed with German artillery—tanks, guns, and ammunition, with the German Luftwaffe flying overhead—defeated southern Spain, the source of Argentina’s folkloristic stage paintings. As democratic and Republican forces were allied to fight the fascist front, Spain had no time to memorialize its heroes, let alone remember a great and heroic dancer. Spaniards were fighting death and hunger; there was no time to preserve Argentina’s memory and her legacy.

Argentina’s contemporaries—dancers, mostly—remembered her legacy until their deaths in the 1950s and 1960s. But they were not writers. They held no political power, wrote no memoirs, published no articles for the Spanish daily press, the mass-media tools that could serve her memory. To this day, several choreographers at the National Ballet of Spain remember her art and her dancing. But they, too, have no ability to revive her memory or to restage her works, to reconstruct and teach her technique, to begin to train a new generation, to be the theater-makers that Argentina once was.

In costume for Tango Andalou, Madrid, Teatro Español, 3 December 1931.

And, of course, the Gypsies who had danced for her held no power to implement a revival or a retrospective. Although Gypsy men had fought alongside Franco in the civil war, Franco turned against the Gypsies during his conquest of Spain in 1940, regularly imprisoning and torturing them as unwanted travelers in his land. Dancers like Joselito and Ibanez tried to build their own nightclub careers, uninterested in Argentina’s memory. They, too, were Gypsies, and in hiring them, Argentina had associated herself with their subculture. But under Franco, no Spanish patron would back a Gypsy who wanted to revive an old boss’s choreography, however great.

Economically weak and physically exhausted, Spanish society was in no position to commemorate the days before Franco. He had been utterly successful in blotting out Argentina, in undoing her good, her nationalistic art, and her individualistic representations. Because her ideas of theater, told through the dramatic device of the moving body—a female form that rotates on its axis, around itself in perfect harmony with the music—had not been recorded, as had the plays and poetry of García Lorca or Valle Inclán, she was to vanish forever, only to be recalled later by a few old people.

Reflections

During the 1930s in the United States, the modern dance pioneers—Martha Graham, Charles Weidman, and Doris Humphrey—believed that Americans must share a common experience, common goals, and a unifying form of expression. Graham, especially, discovered Frederick Jackson Turner’s visionary Americanism in frequent visits to New Mexico between 1935 and 1948. She returned to New York, creating Frontier in 1935 and Appalachian Spring in 1944, the movement recalling the earthy vistas of the American painter Georgia O’Keefe and the chaco canyons of the Anasazi people. Graham danced the wide open spaces of the American West. Similarly, Argentina discovered in Spain—a country both austere and beautiful, harsh and sensual—what Graham had found in America. By interlacing her choreographies with Spanish legends and rhythms, Argentina, like Graham, dedicated her life to what she thought to be its essence, its truth. Argentina beat out the compás of Spain’s forty-nine provinces through her heels, as though she existed in every single space simultaneously, as though she were from every part of Spain’s territory, entering and exiting its churches, fiestas, and funerals. In her own way, she donned the hat of the eighteenth-century Catalonian maja, or threw about herself the mantilla of the nineteenth-century Andalusian peasant woman.

Caricature of Argentina in La Gitane, F.B.M.; by choreographed 1919, music by Valverde, costumes by Federico Beltrán-Masses.

It was Argentina’s reflections on Spain that made her the artistic and cultural spokeswoman for that country from 1914 until 1936. (In 1935 she was invited by Eleanor Roosevelt to perform at the White House.) Her inspired vision gave her a place among the Spanish intelligentsia. Argentina told a story that they, too, wanted their fellow countrymen to read, hear, and see. Through the world of Argentina’s ballets, a new artistic vision of Spain was disseminated. In El amor brujo (solo dances, 1923, 1925, 1928), El contrebandista (solo dances, 1927, full ballet, 1928), Triana (solo dances, 1927, 1929), La vida breve (full ballet, 1928), and El fandango del candil (solo dances, 1921; full ballet, 1928), this Spanish visionary produced, presented, and danced her own modernist masterpieces, theater-works that represented a dancer’s story of Spain.