Читать книгу Antonia Mercé, "LaArgentina" - Ninotchka Bennahum - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление| GIVING GRACE A BODY: FROM THE MUSIC HALL TO THE CONCERT STAGE (1912–1923) Internal rhythm, poetic emotiveness, elegance, plasticity, everything in Antonia Argentina sings a hymn to grace. — El Universal (1915) I believe she both created a new form of dance technique combining the elements of classic technique with all Spanish folklore, as to have the result of a great theatrical art on the stage … but she was so clever that she seemed to have completely forgotten the base technique, to be a real “Spanish Dancer” and not a “ballet-dancer” dancing folklore, what they all do now. — Monique Paravicini | 3 |

At the beginning of her career, performing first in the cramped spaces of Barcelona flamenco bars (1904–7) and then on the vast out door stages of French cafés chantants (1910–12), Argentina relied greatly on the flamenco vocabulary that she had learned from Gypsy women in the south of Spain. Flamenco’s interpretive technique, competitive edge, and highly composite body of individual dance styles nourished her. In search of a movement vocabulary with which to speak, Argentina discovered in flamenco her means of communication. Flamenco’s body, its attack, line, plasticity, elasticity, and dramatic potential, provided it for her. In its emphasis on the way in which the foot attacks the floor, from ball to heel, and in the sinuous reach of the arms into the air, flamenco offered Argentina an emotionally charged dance as well as an expandable musical form.

In the early twentieth-century cabarets of Europe, the dancer filled many roles; she sang, acted, mimed, and danced.1 The French author Colette wrote in 1910, “the music hall has made of me a mime, a dancer, even a comedienne occasionally, but it has also turned me into a very honest, hard-working tradeswoman; the least gifted of women quickly knows her business.”2 She continued, “Music hall artistes are so little known, so despised and misunderstood. They are romantic, proud, full of an absurd and absolute faith in Art. Only music hall artists would dare to declare with sacred fire, as they do—An artiste must not—cannot accept—cannot allow. They are proud, even if sometimes they complain bitterly about that filthy life.” This was the world Colette satirized, and the world that Argentina would leave—Colette’s description of “earning 150 francs a day” would never satisfy a diva like La Argentina.3 (By 1930, Argentina would earn 10,000 francs a night.)

By delving deeply into the musical aspects of the Spanish dance during this early part of her career, Argentina became a success on the music hall stage. She could dance any role—any rhythm—and was becoming a master of the castanets; what was more, she knew she could do it all better than anyone else. But where was she going? What was she searching for? How would she discover within herself the choreographic bridge that would link Spanish musical modernism to the French avant-garde world of visual arts, fashion, and poetry? Indeed, Argentina’s early conservatory training in music offered the link between her visual designs for the stage and her choreographed configurations for her new blend of Spanish dance.

Argentina’s body would, from 1912 to 1923, become the point of departure for a new Spanish dance-theater, as envisioned and executed in performance by its new dance director. By 1921, when Russo-French dance critic André Levinson and French poet Paul Valéry saw Argentina for the first time on the concert stage, Argentina was already thirty-three years old. Slimmer than when she was playing Spanish tablaos, Argentina had emerged into a long, thin, graceful embodiment of “the plastique”—the modernist iconic contour that the American dancer Loïe Fuller had already brought to France in 1892. Argentina’s slimming accompanied her honing, crafting, and refinishing of the choreographic act that would be her communicative vocabulary on the North and South American continents throughout World War I. How could Argentina become a creative agent during a period of political instability in Spain and the widespread killing in Europe? She was young and determined. As an artist and a director, she was unstoppable.

Before she found a way to build her own company, bringing individuality and charisma to whatever small part she was given in Paris by the producers of shows at the Jardin de Paris, the Moulin Rouge, the Olympia, and the Femina music halls, Argentina was like no other Spanish dancer who had preceded her to France. Although she would travel the same route they did, touring South and North America and northern Europe, Argentina would not remain in the the music halls.

Until 1923 when she had her first Parisian concert performance and gave her first lecture-demonstration with André Levinson, Argentina was in search of a venue. She sought a respected place of “high” art-dance, in which she could reinvent the Spanish dance as she came to envision it in 1920s Paris. Argentina’s artistic and geographical journey from the Moulin Rouge to the Théâtre Femina, from Madrid to Paris to Russia and New York, laid the groundwork for her later full-length flamenco theater pieces, El amor brujo (1925) and Triana (1929).

Interestingly, she would never ask her countryman Picasso, who lived in Paris throughout her career, to design for her (although he would paint the modernist sets for Le Tricorne, a Spanish flamenco ballet that was presented by Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in 1919). Argentina wanted to realize her own complete staging, from mise-en-scène to flamenco footwork. That drive helped catapult her into contemporary consciousness, taking her from the commercial stage and placing her on the Paris Opéra stage in 1921, where she presented an evening of Spanish dance and music. Yet she would return to the music halls and to the casinos of Biarritz, Saint Moritz, Nice, and Monte Carlo throughout her entire life, as there she could earn large fees, enough to pay her dancers, musicians, and staff, to rent big-city theaters, and to support her own family (her brother José and his two children) in Madrid.

Argentina had left the Teatro Real de Madrid in 1898, when she was ten, and traveled widely in Spain, and found dance and cultural material with which she would eventually form a repertory of more than sixty-seven solo dances. By the early 1920s, when she was in her thirties, Argentina had become an artist whose vision was transnational; it crossed borders, wedding the artistry of music, scenery, and dance. Then in 1925, she would realize one of the most important Spanish ballets of the twentieth century, one that is still performed around the world today: El amor brujo. In 1923, Argentina had already joined some solos into one-act, formally narrative ballets. In them, she retained her earlier emphasis on the primacy of rhythm as the driving force, the modus vivendi behind any storyline. During her lifelong search for ideas and inspiration, she gathered materials with which she would create seven complete, full-length ballets between 1925 and 1934.

Paris could be grand in 1912. Its cafés were filled with stylish French ladies and gentlemen, and with American and European expatriates, some of them drinking café crèmes at the Café de Flore. Many flocked to all night dance clubs like the Mabillon in Montmartre where a dame seule could dance alone, with a friend, or pay for a partner at a franc a dance. Everyone knew how to dance the tango—a two-step—and many faked Le Fox, or the Fox Trot. Others had heard rumor of the complicated, four-step Le Java dance, but few knew how to execute it. The ladies wore low-backed evening dresses, tight pearl chokers, and high-heeled stiletto shoes. Their long cigarette holders were perpetually held to the side, like some prop in a musical at the L’Empyrée Clichy music hall, where Colette had often worked.4 The men wore shirts with high-necked collars and silk foulard ties. They smoked cigars and stroked long thick beards, which they rarely trimmed or shaved. They wore fitted suits and heavy cloaks, and they twisted and waxed the ends of their long mustaches upward to the sky.

The French dance halls (bals musettes) were a part of every Parisian neighborhood, but they were special in the Left Bank bohemian quarters of Montparnasse and Montmartre. Women and men drank a great deal of champagne in those clubs de nuit in the Champs-Elysées district.5 Poets, painters, writers, and the voyeurs who eavesdropped on the Left Bank frequented Montparnasse. They sat on the café terraces of the Dôme and the Select, as well as the infamous Deux Magots. The literati, such as Hemingway and, later, Jean-Paul Sartre, spent hours on end in cafés observing and talking. Writing was discussed at the Closerie de Lilas café, “across from the old Bal Bullier dance hall,” and discussions were interrupted by people reading one of the eight daily Paris papers.6 By the second decade of the century, the “lustrous, slicked-back” Argentinian tango had become Paris’s new dance rage. Couturier Paul Poiret was accentuating the female form, hugging tight the hips and buttocks, and leaving free women’s naked arms for long gloves adorned with multiple rings of gold and pearl bracelets.

Into this Parisian world Argentina came from Spain in 1910, at age twenty-two (but she often shaved two years off). Following the success of her short number, La corrida, in Valverde’s comic operetta La Rose de Grenade, Argentina felt encouraged by theater managers and the popular press to continue engagements in the music hall venue. Such bookings proved both lucrative and challenging; and, as Colette reminded her readers, they were the place for a fledgling artist.

At the end of February 1912, Argentina left the Olympia Theater in Paris, to travel to Monte Carlo on the Riviera. There she performed in a flamenco operetta, La Bella Sevillana, in which she danced a short solo. According to the Monte Carlo Chronicles, a publication announcing “what’s going on in Monte Carlo,” Argentina was then cast in another extravaganza—“a big spectacle”—called “Espada,” with music by Jules Massenet.7 The show consisted of one hundred and seventy-five dancers. Argentina was one of many principal soloists. It traveled to Brussels’s Royal Belgian Theater, where it had four engagements, and from Belgium to Berlin’s Winter Garden.

In May, Argentina returned to Madrid where she undertook rehearsals for an important engagement. She prepared a series of solo dances to be performed at a private concert at the royal palace on 5 June. Her audience was to be the king of Spain, Alfonso XIII, and members of his royal entourage. Following the performance, King Alfonso presented “La Bella Argentina” with a golden box that housed a pair of gold and pearl earrings, to thank her for her dancing.8 Ten days later, on 15 June, Jacinto Benavente, Santiago Rusiñol, and Romero de Torres, three of the most distinguished members of Madrid’s literary vanguard, had organized an homage to the new star in the house of the Spanish sculptor Sebastian Miranda. They honored her with a portrait of herself, painted by Miranda (which still hangs in the office of the president of the Ateneo in Madrid), bearing the names of intellectuals and artists who admired and adored her: Cánovas Cervantes, Tomás Borrás, Luis Bagaría, Alvarez Quintero, Jacinto Benavente, Luis Bello, Manuel Tovar, Romero de Torres, and Julio Antonio. On 7 December, Argentina debuted in yet another salon, the Salón Llorens in Seville, and remained there under contract until the end of 1912, continuing her flamenco studies and regional folk dance analysis—studies she would pursue for the rest of her life.

Continuing her Salón performances in 1913, Argentina was booked into music hall venues in northern Europe. Everywhere she performed, the local press saluted her castanet-playing, her pretty face, and her dancing. So far, neither the “serious” French press nor the Parisian literati—Paul Valéry, Jacques Rivière, Jean Cocteau, Robert Brussel, Henri Malherbe—had seen her, athough she was hailed as a star in her own country. She played Luna Park in Brussels in early 1913, the Teatro Lara in Madrid, and the Salón Imperial in Melilla. By May, Argentina was performing at the Aquarium Theater in Moscow and at the beginning of 1914, she was performing in London, alongside celebrated Gypsies, in the musical extravaganza El embrujo de Sevilla, there entitled The Haunting of Seville. In this extended engagement at London’s Alhambra Theater (where Diaghilev would premiere the Ballets Russes’ production Le Tricorne in 1919), Argentina was billed as a principal dancer and as a castanet-player. She was performing alongside artists and musicians from whom she had learned, those whom she most respected.9 The show went on to extended engagements in Paris, as well as in London, awarding Argentina as much publicity as a Spanish music hall artist could want.10

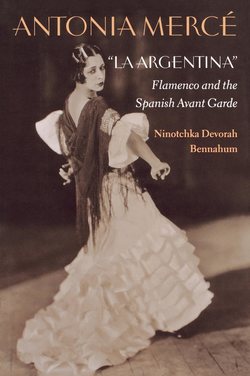

“La Reine des Castanettes,” “Queen of the Castanets.” Argentina posing in her original costume for La Corrida, 1916.

Having toured Europe and Russia, as part of one of several French and Spanish music hall acts and in musical theater works, and having played the Parisian theaters, Argentina was ready to break with other people’s shows. She wanted to continue to create her own work and to be her own artistic, musical, and dance director.11 After a decade in the music halls of Europe, from 1904 to 1914, she was prepared to try to make it on her own. She was also in search of herself: in flamenco, she had discovered a rhythmic heartbeat much like her own, a soulful and soul-stirring source of inspiration.

Like ballet, flamenco’s lines were strict, requiring a particular body carriage, positioning, and dance steps to form a sequence. Flamenco had an internal vocabulary all its own, and in learning and expressing it, Argentina could only become a great flamenca. She could never be of Gypsy ancestry, and she could never completely return to the Spanish classical tradition that had trained and fed her for the first decade of her professional life.

Instead, in France, with its elegant Beaux Arts backdrop and new Art Deco lines, with its “liberated” women, its cafés, its artists and writers, Argentina had found a new way of seeing the female and of investigating the possibilities of shape, outline, motion, color, and power. She would soon take the potency of flamenco verse, the anxiety of its cante and its earthbound rhythm, and go on to generate a composite of what she most admired on the streets of Paris, fashioning it for the stage in the image of the Ballets Russes’s productions. She became herself as she wanted to be, at a time—August 1914—when the twentieth century was turning cruel and falling into World War I. With Tsar Nicholas IPs mobilization, Germany and Austria were fighting France, Russia, and Great Britain—and by 1917, the Russian Revolution began in earnest. The war ended in 1918 with the highest death toll ever on French soil at the Battles of the Somme and Verdun.

Argentina spent the war years on tour in South America. By 1918, with the armistice, Argentina would find herself back in Paris and the city would welcome her look, her dance, and her performances as part of postwar Parisian life. The Paris Peace talks, which settled the postwar treaties—and asked Germany to pay huge reparations—and established new European borders, focused great attention on the French capital and in nearby Versailles. After several years of their international diplomacy and their diplomatic high life, the talks ended. Paris night life would soon be changed by Russian, Jewish and Eastern European exiles and American expatriates. It was the roaring twenties.

Two late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Spanish dance hall stars had, in a sense, paved the way for La Argentina to leave the music hall behind her and take to the stage of the Paris Opéra, the Opéra-Comique, and the Femina theaters. Carmencita, the “Pearl of Seville” (1868–1910) and Carolina, “La Belle Otero” (1868–1965), each in her own way, had demonstrated the strengths of the Spanish idiom to be more than unspoiled exotic Gypsy ritual or the mere representation of regional folk dance; in their own ways, each showed flamenco’s earthy sensuality and boldly classical verticality to be both feminine and balletic, formal yet mystical. Further, each demonstrated the theatrical possibility inherent within the Spanish and Flamenco genres.

Both Carmencita and Otero had appeared as the exotic “other,” playing on the myth of the seductive, licentious Andalusian Gypsy woman. They energized numerous dance acts, injecting a highly sexualized performance of sinuous femininity that traveled beyond exoticism, projecting the idea of a Spanish dancer who might become something beyond the “ethnic” act—a performer who was not just the family breadwinner but, perhaps, an “artiste.” They each had a certain special rhythmic, and therefore dramatic, story-telling capacity. Carmencita’s fandango, performed on a tiny New York music hall stage in 1890, “filled with tobacco smoke,” displayed a “poetry of motion” that was “revelatory, sensational, and devastating” to the viewer’s eye.13

One spectatator in 1890 had recalled Carmencita’s performance as the appearance of youth—much as Loïe Fuller’s symbolist followers would describe her skillfully lit appearance. Carmencita’s “graceful and sinuous movements and ever-changing attitudes” displayed “a flexibility of body” performed in “an abandon of the physical” that is “perfectly astonishing.”14 Another writer remembered her “impassioned moments” of dance as the display of an “extraordinary personality that seizes the beholder and leaves him mystified with the power of their effect. She is [indeed] the incarnate harmony of form and motion. She is art personified.”15 Interestingly, as early as September 1890, “modern,” a word that would be used to describe Argentina’s South American performances between 1915 and 1918, had already been used to describe Carmencita’s predecessor.

By the late nineteenth century, an interesting Spanish “art” dancer on the New York music hall stage had toured America. Like Carmencita, who has been captured in William Merrit Chase’s 1890 impressionistic painting, Carolina Otero also performed on New York dance hall stages. Unlike Carmencita, whose performance was considered a “curious mixture of feminine chastity” and Spanish “passion,” with multilayered skirts offering perhaps the best reminder of Sevillian Gypsy dancing, Otero preferred to play the Spanish diva, costumed in a white flounced gown that fell outside the traditions of her native Spanish origins.16 Although La Belle Otero could pull off the traditional 1890 crowd-pleasers—the seguidillas, jotas, boleros, tonadillas (ditties), and the singing that accompanied some version of the original cachucha17—it was her modern street dress combined with just a hint of an “authentic” Spain that helped make her a music hall star.

Where Carmencita’s performance was “one of recklessness and wild energy, Otero displayed delicacy and finished appeal.”18 Carmencita, indeed, particularly embodied “the dance of Andalusia,” and between 1890 and 1910 both women had become huge stars, drawing crowds for music hall owners and producers. But neither even considered going beyond the commercial venue and onto the concert stage. Otero left and became known as a courtesan; Carmencita remained a popular sensation until she could no longer dance. With all of Carmencita’s dancing ability and charisma, her connections to painters like Sargent and Chase, and her many imitators in New York, she never saw herself as more than she was. As for Otero, although considered quite a good singer, a woman of elegant demeanor, and a “high-class” stage presence, she never thought to use this modern flamenca of her own making as a new way of looking at the Spanish dance. That is to say, the entire idiom—the techniques of both flamenco and Spanish classical dance—did not seduce either woman. Neither artist saw beyond the venue at hand, beyond the potential producer or the envious admirer. Yet they prepared the way for Argentina to go beyond mere replications of the Spanish dances.

Argentina would play on both women’s talents, influenced by their costumes and their commercial, clever choice of songs and dances, in order to catapult herself into contemporary consciousness. Argentina was, indeed, combining the modern image of woman with the Romantic sylph. Her modernism was flamenco; her Romanticism was eighteenth-century Spanish court. Eugen Wolff described this type of self-inscribing, individualistic artist in 1888 as a contemporary spokeswoman: “a modern woman, filled with modern spirit, and at the same time a typical figure, a working woman, who is nevertheless saturated with beauty, and full of ideals, returning from her material work to the service of goodness and nobility, as though returning home to her beloved child. She is an experienced but pure woman, in rapid movement like the spirit of the age, with fluttering garments and streaming hair, striding forward. That is our new divine image: the Modern”—the Modernista.19

Carmencita was the Spanish dancer who truly established a way for Argentina to move out of the music hall and onto the concert stage. Unlike Otero and especially Carmencita, Argentina would do nothing but work. From her letters and touring contracts, no mention of sitting in cafés, or even walking around New York or Paris is to be found. Everything that Argentina did was somehow tied to dance, music, and theatrical productions—unlike her predecessors, who were often in attendance at social events. And with her musical lyricism, her austere beauty, and her utter seriousness, Argentina inspired a certain high-mindedness that existed both in her own thinking and, later, in the critiques of those who wrote about her. If Carmencita’s and Otero’s personal lives ended up “undermining their art,” Argentina’s life revolved continuously around her dancemaking.20

In an important way, both Carmencita and Otero had prepared Parisian mixed audiences for a strong, potent, very visible female body on the turn-of-the-century public stage. They had both displayed the Spanish dancer as one of skill and rhythm, whose first objective was not to shock the spectator. Rather, both performed with strength and agility, with pride and humor, allowing Europeans and Americans to “discover,” not fear and avoid an overt display of the female form in motion. Whether at first these imported flamencas were considered as moving sculpture—the subtle means toward acceptance of their femininity—was not so important as the idea that they were revealing knees, arms, and backs in front of an audience who was used to some greater costume coverage. Only in the infamous, disreputable nightclubs were women showing their parts to mostly male patrons (while dancing the cancan, for example).

On tour in London, 1933.

From Otero and the many other Spanish dance artists touring at the time, Argentina may, indeed, have learned what she did not want to be: a woman dressed in seductive layers of lace and pearls. Did Argentina’s fascination with scenery and fabric—important elements in the Paris of the day, in the staging of both the popular Loïe Fuller and the scandalous Ballets Russes, and in haute couture design—reveal a connoisseurship of Carmencita and Otero? Argentina would abandon the multiple skirts of the Art Nouveau period—the Gypsy flamenca’s polka-dotted dress that left a slender waist but puffed up a woman’s hips, modestly hiding her thighs and knees—shortly after her return from her South American tour of 1915. Instead, she would modify her costume and thereby make herself even more slender, asking her designers to lengthen the line of the skirt by first dropping the back into a V