Читать книгу Antonia Mercé, "LaArgentina" - Ninotchka Bennahum - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление| THE FORMATIVE YEARS (1888–1912) I serve a mute art and seek the full range of expression through step patterns, through the unfolding of movement, and through the use of mime. My surest vocabulary proceeds through my ankles, my arms, my hands, the lines of my body, and the expression on my face. I like and am accustomed to making myself understood in silence, or rather, adding only to my silence the musical voice far from words, which I find of somewhat limited use. I really believe that as a result of asking nothing from words in the practice of my art, I have learned to live at a certain distance from them. — La Argentina, quoted in de Soye, Toi qui dansais, Argentina | 2 |

Antonia Rosa Mercé was born in a boardinghouse in central Buenos Aires on 4 September 1888. Her parents were dancers who earned a little extra money touring South America with a company of stars from Madrid’s Teatro Real. Like the Russian Imperial Theaters (the Maryinsky), the Teatro Real enjoyed royal patronage; King Alfonso XIII loved dance, mime, music, painting, and pretty women. Under Alfonso’s watchful eye, the Teatro Real engaged Italian and Spanish dancing masters, considered the best, to train his corps de ballet and principal soloists in the complex art of French, Italian, and Spanish theatrical dance.1

By the end of the nineteenth century, the Teatro Real de Madrid and its affiliated academy, the Royal Academy of Dance, had come under the influence of the Italian teachers and their choreographic practices.2 Argentina’s father, Señor Mercé, taught Spanish classical technique, a court form that required musical precision, focus, muscular strength, and balance.

The Spanish classical school’s main step—the bolero—was, as Carlo Blasis described it in 1831, “a dance far more noble, modest and restrained than the fandango,” that Moorish-Gypsy dance that Argentina would later incorporate into her Spanish classical repertory. While the Italian ballet emphasized the linearity of the upper torso, the body held in seemingly weightless and effortless poses, the Spanish technique required the dancer to become the musical line; it used the body as a means of expressing the music. The body became the musical agent, the accompaniment to the castanets.3 The Spanish dance was, indeed, less concerned with the outline or contour of a dancer and her posing and more evocative of space and time. The Spanish school—the escuela bolera—in particular, was a technical dance form; its emphasis lay less on the aerial flotation or bodily extension out into space that was typical of Italian ballet and more on how well the dancer used quick moves of the head, arms, and feet to express emotional states. The escuela bolera was the technique to which Señor Mercé dedicated his life, in which he reluctantly trained his daughter.

Argentina’s father, Francísco Manoël Mercé, native of Castile, was one of the dancing masters. Born in Valladolid in the year 1860, forty-five kilometers from Madrid, Mercé was both primero bailerin and maestro.4 He was considered to be a “a remarkable technician” in his prime.5 In a 1936 interview with French biographer Suzanne F. Cordelier, Argentina described her father as “a great interpreter of the Spanish schools of dance”: the Spanish classical school, the Franco-Italian classical ballet school, and the many Spanish regional dancing styles.6 Argentina, influenced by her father’s training system, took these three schools recognized by the Spanish dance academy and combined them with Gypsy flamenco, thus recognizing Gypsy dance as a fourth school, an aesthetic genre of its own. Taking the flamenco technique out of its folk dance categorization and placing it on an equal footing with regional dances of the Spanish classical technique, Argentina refocused the training and, therefore, the sociocultural aesthetic of Spanish dance tradition. Placing flamenco and Spanish classical dance together with western and northern European ballet traditions, Argentina transformed Spanish dance, organizing its schools through modern(ist) dance steps, the basis for her fame and her legacy.7

The boarding house in Buenos Aires where Argentina was born on 4 september 1888.

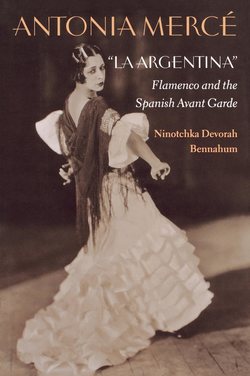

Argentina posing in costume for Suite Andaluza, 1935.

But Argentina criticized her father claiming that “he went no further…. He never created…. He didn’t live through his soul. For my father dance was a body of cold and very solid rules, as dense as lead.”8 This is a very harsh criticism from a forty-eight-year-old woman, clearly mature and successful in her own professional career when giving this interview. However, Argentina’s open anger and frustration at her father’s inability to go beyond academic strictures must have felt suffocating to her as a child. The quote bears witness to Argentina’s rite of passage, from young student of her father’s to innovator and reformer of the Spanish classical training system.

Although Cordelier relied heavily on Argentina’s memory, so many years after the fact, she was careful to include the words of the Spanish dance critic Luis Montsalvatge, who completed Mercé’s daughter’s critique with praise: “He was a dancer of the trade,’’ claimed Montsalvatge, “full of technical knowledge…. Manuel [possessed] irreproachable technique…. [He was] a true and loyal performer.”9

Manoél Mercé was trained in all styles of traditional Spanish classical dance. As a dancing master he transmitted this knowledge of the three schools of the Spanish dance to his many students, most of whom came from Madrid’s wealthiest families.10 As premier danseur, Mercé also functioned in the capacity of teacher at the Music Conservatory, prepared both by his performance experience, as well as his stylistic knowledge of the form. His training of dancers was considered “rational and rigorous.”11

Mercé was a strict disciplinarian. He never veered from the traditional styles he had learned; he never extrapolated upon them and he was strict and demanding. Cordelier cites this conventionality on the part of Argentina’s father as one reason for her desire to break out of the traditional Spanish dance in order to express herself.12

By 1880, Mercé had become the theater’s principal dancing master, or maestro de la escuela bolera.13 His title informs us that he specialized in the dances of the Spanish classical school: the boleros of Catalonia, peteneras of Andalusia, the jota (a dance closely associated with Aragón), Basque dances, and the western European ballet traditions of Jean-Georges Noverre (1727–1810), Jules Perrot (1810–92), and Enrico Cecchetti (1850–1928).14

On tour at the Teatro Municipal in Córdoba, Spain, Mercé met Josefa Luque, “a pretty young Cordoban … who belonged to an old Andalusian family” that had lost all of its money.15 As she was very beautiful and of good family, she had received many marriage proposals, but turned them down, thinking that a poor woman had no right to marry a wealthy man.16 Mercé was not a rich man, nor was any dancer attached to a large European theater with a corps de ballet of roughly one hundred, as well as principal dancers on the payroll.17 It is curious, however, that an upper-class family would have allowed her to marry a dancer at all.18

The Andalusian folk dance, sevillanas, and the boleros were often taught to young girls in late nineteenth-century Spain. Further, a girl from a good family would have been sent to dancing school, dance being considered an accomplishment for a young girl, and a good influence on a maturing adolescent. It seems only logical that Josefa had studied dance as a teenager and had returned to it later in life upon marrying Maestro Mercé. Although Argentina herself, in a 1936 interview with Elizabeth Borton, describes her mother as having begun dancing at a late age, the rigor of the jumps of the jota and the stamping footwork required by the peteneras would have made it impossible unless she had started as a girl. Argentina tells us that only a Spanish woman can “move as a Spanish woman … can walk in a Spanish way … portraying the mannerisms inherent within a Spaniard”19 Perhaps it was for this reason, that Argentina would have surmised her mother able to take to the stage without prior training at such a late age. In any case, if all young Spanish women learned boleros, perhaps the few from good homes became ballet dancers.20 (Middle-class Andalusian girls and boys were taught the seguidillas sevillanas, a Sevillian folk dance of Moorish, Spanish, and Sephardic origin adapted by Gypsies and passed back to Andalusian Spaniards at fiestas and weeklong fairs.) They were not brought up to lead the existence of a dancer, touring at times without chaperones, able to earn their keep and make their own decisions.

In Madrid, Josefa, a kind and loving woman according to her daughter, studied privately with her husband and, by the age of thirty-three, became primera bailerina at the Teatro Real. At times, she danced alongside her husband. At such an advanced age for a dancer, she would only have been considered for certain dances. Most likely, she would have been considered a bolera, or a Spanish “fancy-dancer.”

Boleros required jumps, quick turns, and turns of the leg accompanied by a tightly held upper body carriage while playing the castanets. Even a determined dancer, such as Josefa Luque, however, could have attained no more than bolera status.21 She might also have danced peteneras, jotas, and valencianas, required dances at the Teatro Real in the late nineteenth century.22 Her ability to dance at all is questionable. Perhaps her family status was exaggerated by her daughter and she was sent to dancing school in order to learn a viable profession. Josefa Luque must, however, be seen as an ambitious, creative woman who loved the theater. Luis Montsalvatge described Josefa in relation to her husband: she was, “in contrast to [Manoël] … more sophisticated, with a kind of aristocratic intelligence…. [She] possessed the gift of grace to a lofty and resplendent degree.”23

In speaking about her parents’ extraordinary marriage and her mother’s ability to learn the art and craft of dancing at such a late age, Argentina speculated that it was her mother’s creativity and her father’s ability to teach—to break down a combination into a simple, comprehensible series of steps—that enabled her mother to become a principal dancer so late in life. (It was an almost impossible feat in any period of dance history as the essence of the dance is training the body to learn physically from an early age, giving oneself, through one’s body, an innate consciousness about space and time that is physically communicated between mind and body.)24 But Argentina also attributed her mother’s ability to perform so late in life to her father’s authoritarian personality. She described him to Cordelier as a strict disciplinarian, while her mother was a more loving, emotional caregiver. It is no wonder that her career began after her father’s death.

In 1892, the Mercés returned to Madrid, settling in a middle-class Salamanca neighborhood. They took up residence in a small house with a drawing room large enough for Mercé to continue giving his evening lessons. Her father’s private pupils frequented the Mercés’ living room late into the night for tutorials with the maestro. In this work-filled, artistic environment, the four-year-old Argentina was exposed on a daily basis to Spanish dance. Unhappy that she might become a dancer, Mercé insisted that she study music, an art cultivated by all aristocratic young girls.25 Argentina was sent to the conservatory to learn music theory, general music history, singing, and castanets, all of which she detested.26 Josefa “saw her daughter as a singer” and was determined that she go onstage as a “lyric artist” of some kind, even if she did not become an opera singer.27 In the ultraconservative atmosphere of turn-of-the-century Madrid, singing was considered an acceptable profession for a young woman, if she were to have a profession at all. To be a dancer, however, wearing few clothes, dancing, perhaps, in a music hall or a singing café, was thought totally unacceptable by Victorian and Catholic standards, especially for a girl from a good family, even a dancing family such as the Mercés’.

Cordelier’s biography contains a number of quotes from Argentina about her father’s surprised reaction to her youthful triumph in Córdoba. Argentina’s memory of her father’s prejudice against her dancing must be seen in its context. Speaking in hindsight, forty-four years after her debut, Argentina remembered her father as helpful by osmosis, never encouraging, except in the area of music. And musicianship was to launch Argentina to international stardom as the greatest castanet-player the world had ever known.

Argentina’s father wanted her to become an excellent castanet-player, as well as a singer. For Señor Mercé, the castanets represented the soul of Spain, her history and culture. A delicate instrument that could accompany song and dance, they would provide the musical sensibility that would enable his daughter to understand rhythm. And for a maestro of the escuela bolera, the castanets were a symbol of an accomplished Spanish artist. They were, he felt, an upper-class pastime, reminiscent of Goya’s picturesque, pastoral scenes in which the nobility clicked their castanets as they passed one another in couple dances performed in immense ballrooms.

In late nineteenth-century Madrid, castanets symbolized both aristocratic majas and majos, as well as poor, classless Gypsies. It is only necessary to look at the Gypsy drawings of Gustave Doré and John Singer Sargent, and the café cantante (singing café) paintings of Joaquín Sorolla and José Llovera, for evidence of the vast use of castanets by Andalusian Gypsy flamenco dancers.28

If played with attention and care, the castanets created a sonorous, almost airy sound. At the turn of the twentieth century, castanets were used by Gypsies and non-Gypsies as accompaniment to flamenco dance. After the Spanish civil war, castanets were no longer used to accompany flamenco, but were retained for escuela bolera. With Paco de Lucia’s jazz improvisations in the 1960s and 1970s and the death of Franco in 1975, castanets were once again seen on the hands of the flamenco performer. Who revived their usage and at what exact moment they were reincorporated has yet to be studied. Further, one must ask whether Flamenco performers’ prejudice against the Spanish castanet was a Franco-era holdover or a postmodern reaction to a light-sounding, aristocratic instrument that viewed the castanet as a conflation of eighteenth- and twentieth-century socioeconomic and political values.

For his daughter, learning them was a lesson in concentration, discipline, control, and musical perception. Further, if played with authority and dignity, the castanets could awaken patriotism and delight in most Spanish audiences, bestowing upon the performer immediate and laudatory acceptance as a high artist in the Spanish tradition of theatrical performance. It was, therefore, no surprise that castanets were featured in Argentina’s first solo performance outside the Teatro Real, which took place in 1905 on the concert stage of the Romea Theater. There, “on a splintering floor,” Argentina sang, danced boleros, and played the castanets in public for the first time.29

In a 1932 London interview, Argentina recalled her first reaction to these small, unassuming hand instruments:

When I was little, barely five, I constantly heard castanets in my parents’ house, as they taught dance lessons. This anti-musical sound irritated me to the point where I hid in the farthest room of the house to escape its echo. There I practiced my girlish fingers on a pair of little castanets that my father had given me. I was forcing myself unconsciously (since, at that age, one doesn’t reason) to get sounds out of that instrument, sounds that would not hurt my ears like the others. Those were my beginnings in the art I now practice, and I can very well say that the liking I took to my castanets followed my dislike of the castanets of others.30

It was not until she left the Teatro Real that she took a real interest in what it meant to play castanets. After several years of training herself, however, Argentina became a maestra. She recalled that “I ordered castanets to be made with a variety of different degrees of concavity.31 The castanet-maker was furious, saying that I was trying to tell him how to do his job. My response was that, in return for his work, I could sell the whole world castanets that he was already making; but for my own use, I needed the others.”32 As Vicente Escudero recalled so poignantly in his memoirs, Mi baile, Argentina became not only a great castanet-player, but a connoisseur of the instrument itself. “I believe the secret was in the artist herself,” he said, “and she has taken it with her to heaven, because up to this point, no one has managed to reproduce it, and no one ever will. Although she was the creator of the school of playing that everyone cultivates today, they all lack the genius of the master.”33

By the age of seventeen, however, as she toured Spain and South America as a solo concert artist, when Argentina was asked about her castanet-playing, she became almost dismissive: “That’s not worth talking about,” she exclaimed. Castanet-playing “is not something one learns; it comes from far away.”34

Also at the age of four, Argentina began to dance, having watched her father’s nightly classes from behind a curtain in the living room.35 She remembered: “As my parents refused to teach me to dance, I learned by attending the courses they were giving.”36 Imitating the classical tutorials of her father, Argentina learned to dance by practicing the Spanish classics: the cachucha, as well as the jota of Aragón, the hundreds of dances from the Basque provinces and Navarre, and the valenciana from Valencia.37 In 1893, at five years of age, Argentina found herself dancing a lead part in one of her father’s ballets in Córdoba, as the original dancer had been injured. Argentina begged her father to let her play the role. At first, he declined. So she danced it for him, having seen the original star execute the movements. Argentina made no mistakes. The maestro was desperate, as this was a performance for royalty, and at last he agreed. Argentina not only completed the dance without faltering, but did so with such clarity and fluidity that she received enormous applause. Although her father remained, until he died, opposed to his daughter dancing, he could not but tell her she had danced well and had understood the rules of the Spanish dance without lessons.

Argentina with the castanet maestra Orfilia Rico, taking a tutorial, 1915.

It was after her enormous success in a popular zarzuela, The Nephews of Captain Grant (1894), however, that Manoël began coaching his daughter.38 Only seven years old at the time, Argentina executed the difficult dance of the zamacueca, once again replacing the premier sujet, who was taken ill suddenly during the company’s tour. Small and thin at the time, Argentina danced the zamacueca with “grace and elegance,” adding to the dance number a special personality.39 At the turn of the century, zarzuelas were Spanish operettas based mostly on satirical themes.40 Spoken dialogue and sung text carried the story alongside large dance scenes. Within the popular zarzuela comic musical, one could attain fame among a large section of the Spanish population. Immensely popular until the Second World War, they allowed celebrated performers the chance to appear before a large audience. The early twentieth-century Spanish popularity for the zarzuela theater prepared Argentina for the music halls she played in Paris. She had acquired a taste for variety acts, getting used to performing on the same program with a film, a dog, an acrobat, a singer, as well as to condensing her solo if time was short.41

Argentina’s hands.

Merce now placed his daughter at the barre in the living room, teaching her the fundamentals of the Spanish technique.42 Between 1899 and 1903 she began seriously studying music and dance at the conservatory. At the end of 1903, her father had a stroke and was left paralyzed, unable to dance, teach, or even to walk. His wife took over his evening classes and, in December, when he died, Argentina began to help her in order to pay the household bills.43 Her mother also supplemented her father’s lessons by tutoring her in music. By 1904, Argentina had succeeded in passing all the dance examinations while purposely flunking the examinations in music, except for castanet-playing.44

With Mercé’s death, the fifteen-year-old Argentina took her fate into her own hands. She would sever her ties to academic Spanish dance, devoting her life to its origins. “My parents only knew classical Spanish dance, in the tradition of the escuela bolera…. Flamenco and folk-dancing were unknown to them. I read all I could find out about it; I ransacked secondhand bookstores, now and then finding engravings.”45 Argentina began to develop an insatiable appetite for ethnographic accuracy and her desire to methodically study dance forms would follow her throughout her career.

Argentina’s early repertory (1910–15), significantly drew upon the bolero tradition. She used the bolero both as a choreographic tool and as a dance style incorporated into an extensive and evolving movement vocabulary. Argentina used the bolero as a solo and not as a couple dance. It allowed her to demonstrate both extremely technical, classical technique while accompanying herself with castanets and quick changes of direction. In using the step and the style of the bolero school, Argentina paid tribute to the artistry of her parents while developing a modern sensibility on an old-fashioned form. She juxtaposed it and changed the actual Spanish dance in relation to Gypsy flamenco footwork and armwork. Together, the light bolero jumps and turns, combined with the earth-centered Gypsy dance, created a dual-national Spanish dance from the eighteenth to the twentieth century.

For Argentina, the bolero could only work on the modern stage in conjunction with flamenco. Flamenco’s technique of florea and braceo, the intricate and sinuous carving of space with shoulders, hips, hands, head, and feet, were executed in conjunction with Spanish classical bolero steps. Through the insistent rhythms and articulation of hands and feet, Argentina would incorporate flamenco into a total physical expression of the Spanish dance. For Argentina, then, the airy, ephemeral technique of eighteenth-century Spanish dance, combined with the mechanized, razor-sharp edge of twentieth-century flamenco interpretation helped her to build a bridge between Romantic visions of an ethereal woman and modernists’ attraction to seemingly architectonic bodies—speedy and self-confident. In Argentina’s romantically modern universe, the ballet sylph meets the urban woman, dressed in Gypsy robes, a kind of arcadian bliss mixed with self-satisfaction in which early twentieth-century artists swam.

Caricature (1934) of Argentina in Belero clásico by Iradier, at the Théâtre de l’Opéra-Comique in 1929.

Performance of Bolero Clásico, 1929, costume by Iradier.

From this initial literary exploration of Spanish folk forms, Argentina, being a dancer, decided that the best way of learning the flamenco dance styles was to do them. Several months after her father’s death, Argentina accepted an engagement in a Sevillian café cantante, and, performing as part of a cuadro, or flamenco corps de ballet, earned enough to pay her room and board, dancing at the beginning of the evening, as the stars danced last. Next, Argentina observed the flamenco greats of the period, including La Macarona and La Malena. Argentina then auditioned for the permanent troupe of the Teatro Variedad.46 She performed well. Out of roughly fifty flamenco auditioners, Argentina, although still relatively unfamiliar with the enormous repertory of flamenco lettras, performed the “Soleares de Arca” successfully and was accepted into the company.47 “I worked for one year in this theater,” recalled Argentina. “I earned five pesetas a day.”48

In the summer of 1905, Argentina moved to Barcelona for a one-year engagement dancing in a flamenco tablao (show). She debuted as a flamenca on 1 June at the Allaran Español music hall.49 She was miserable. “They all made my life unbearable. People laughed at me and criticized me, but paradoxically, imitated me…. They thought my dance style was refined and stylish.”50 What dances Argentina performed in Barcelona remains unknown, although she was most likely one of many young women included in an all-female cuadro that filled in between solo dances in order to give the principals time to rest. She learned rhythms through imitation, perhaps soliciting advice and demonstrations from more experienced Gypsy dancers. Both flamenco and Spanish classical technique require a controlled, vertical, yet elastic upper torso, Argentina had been trained at the conservatory to interpret dance well. She quickly understood the complex, rhythmic hierarchy required by the flamenco canon: a head that moves in contratiempo to the feet, counting rhythm, turning from side to side, right to left. It was most likely the initial footwork (zapateado) and the accompanying sung verses (coplas) that proved most difficult for Argentina to master. But a Gypsy community utilized the innate sense of rhythm created by singer, guitarist, and dancer. (She would return again in 1908, with a growing reputation among Spanish and South American intelligentsia and balletomanes. This time, she would go to the Teatro Arnau and the Salón Doré.)

In the early twentieth century, Barcelona was the most industrialized region of Spain, as well as its leading commercial center. Although frequented by Gypsies, the city’s tablaos were filled with foreigners, also doing business in the Catalan capital. A common evening entertainment was the flamenco café or bar where Spaniards, European businessmen, flamenco aficionados, and tourists gathered. In this atmosphere, Argentina danced and perfected her knowledge of the complicated flamenco technique. The flamenco cuadro was in no way protected from its audience, which was composed, at times, of rowdy drunks. The café owners in big cities like Barcelona were not always flamenco experts, or aficionados, but businessmen interested in profit. The well-being of female performers, each one easily replaceable if she complained, was overestimated. And, unlike the Teatro Real, where dancers came under the scrutiny of teachers, rehearsal mistresses and masters, and directors, a flamenco company could easily be harassed by the boss.

It was in this gritty, unsafe atmosphere, where one appeared with guitarists, singers, and fellow dancers who could alter rhythms during performance, along with the uncomfortable nature of dancing in a bar, that Argentina began to learn what rhythms underlay the dance and song of the Gypsy. After a year, she left and traveled west to Seville. There she studied intensively with gitanas flamencas, fat, elderly dancers who taught her as many step patterns and rhythmic sequences as she could absorb. She departed for the French capital at the end of 1905.

Argentina obtained a three-month contract at the Jardin de Paris, dancing as one of a hundred “girls” in the corps. The Jardin was one of the largest outdoor cafés chantants in Paris, and therefore, a very visible place to begin a French career on the music hall stage. Located on the edge of the Place de la Concorde, on the leffhand corner of the Avénue des Champs-Elysées as one faces the Etoile, the Jardine’s tables were shaded by the treetops of the Champs-Elysées.51 “Between a tyrolienne singer,” wrote Edouard Beaudu, “and a baronne who does his haute école, Argentina danced and astonished. Her thin arms, held just above the head, the soft clack of her heel-work, and her hands always beating the castanets… She was a goddess with a long train behind her”—the traditional bata de cola.52 Dancing several months in Paris, she returned to Spain, again picking up her engagement in Barcelona.

Although Argentina was unhappy dancing in Barcelona, she cited in her essays her early work in peñas (flamenco bars) as the beginning of her flamenco education. For the next few years, aside from dancing to support her mother and brother, Argentina became totally absorbed by the study of flamenco, its rhythms, singers, guitarists, dancers, and castanets. These instruments Argentina eventually made the protagonists of entire orchestral performances, although she had never considered them concert instruments in their own right. Castanets and the intricate zapateado sequences would become Argentina’s signatures, countering time with time, answering the arpeggios of guitar, violin, and voice.

Within the flamenco genre adopted and later adapted by Argentina, time represented everything. Representing only an idea—the idea of itself on the stage—time was revealed to the audience through rhythm and counterrhythm produced by dancer, solo guitar and piano (and in Argentina’s more mature works, through the fluid interaction between orchestra and dance company).53

In the beginning stages of her solo career, however, Argentina adhered closely to the flamenco vocabulary’s basic features: time and meter. The elements used to produce tempo and dynamic change in flamenco were footwork (zapateado), clapping (palmas), singing (cante), guitar arpeggios (toque and rosqueado), and Argentina’s hallmark, the castanets (las castañuelas). These rhythmic accompaniments underlay every musical score and choreographic composition created from the moment she began original solo compositions in 1910 until her death in 1936.

The Gypsies of southern Spain taught Argentina how to reproduce time, how to multiply and fracture it so as to compose new tempi, new rhythms. Through multitudes of polyrhythmic formats, Argentina learned to engage an audience. The Gypsies’ clapping, snapping, and footwork taught her how to extract rhythm from rhythm, how to create and to use music as a dramatic character, thus producing the story of itself, a tale about music.54 Time for the Gypsies, then, as transmitted to Argentina, was and remains an abstraction, one so powerful it represents life. By 1910, Argentina, like Falla, was to incorporate the flamenco verse (copla) and the flamenco rhythm (compás) into the turns, kicks, and jumps of the escuela bolera, thus forging an intensely dramatic connection between poetry, music, and dance.

Thus, in Argentina’s fusion of Gypsy flamenco with Spanish dance, rhythm spoke narrative, as well as accompaniment. It was a means of telling the story, providing variations on that story through contratiempi. The castanets clicked as the arms formed circles in the air, accompanied by the drilling of the flamenco shoes on the floor. An intertwining of body, producing rhythm with drama, thus unfolded.

The role played by the voice—the cantaora, as the singer is known in flamenco-provided, perhaps, the most important musical line. Throughout her career, Argentina never forgot the cante, choosing Ninon Vallin, Marguerite Beriza, María Barrientos, Alicita Felici, and many other great women singers, to accompany her on stage, together with guitar, piano, and, at times, a fifty-member orchestra.

As an American critic noted in 1916, Argentina possessed an innate sense of time: “a perfect sense of rhythm gives her performance an exceptional perfection … in the liveliness of her dances… she executes delicately, and not by way of vigor or simple muscular control. She is also a virtuosa in the playing of the castanets, in which she has never been outdone.”55 Argentina would begin every ballet she created, conceptually, through a written score executed by Manuel de Falla or one of his students. She then superimposed on each score the rhythms of her feet, head, and hands. Onto those polyrhythms, Argentina added those of her company. With this massive musical resonance in mind, she began to choreograph. This intensive focus on rhythm she learned from the Gypsies and from observing her father beat out rhythms with a cane (known in Spanish as a palo seco), standing before his private students at night, and from her early musical training at Madrid’s Conservatory.

Argentina with Spanish open singer and close friend Maria Barrientos, London, 1931

At the end of her year’s stay in Barcelona, Argentina formally resigned from the Teatro Real. Although deeply unhappy dancing in a flamenco bar, Argentina chose an even more difficult route, the intensive and private study of flamenco rhythms. Josefa kept the house on Olmo Street, but she had closed it, once again, to accompany her daughter to Seville in early 1904. This trip marked the beginning of her career.

In her quest for the deepest personal understanding and physical experience of the Spanish dance, Argentina trained all the day in, zapateado, compás, and in an ornate and articulate style of holding the upper torso, head, and arms while the feet drilled out time.56 What was not so alien to Argentina was the body carriage of the gitanas flamencas, who held themselves upright, at times swaying arms and hips from side to side, but always with control, agility, and strength. It was, indeed, the carriage of the waist to the head that came naturally to Argentina, as it was not so different from the upper-body carriage required in the escuela bolera.

Argentina’s formative education in how the female Gypsy carried her upper-body weight and framed her face with bent elbows and wrists was further reinforced by an intensifying awareness of florea (the flowering of the hands and fingers). The arms traced continuous circles, beginning at the shoulder joint, continuing to the elbow joint, and breaking at the wrist so as to leave the fingers free to form endless circles, akin to the Indian mudra.

In August 1906, Argentina was invited to tour Portugal. The flamenco cuadro was to be directed by the celebrated cantaor Antonio el de Bilbao, with whom she would later share a London booking at the Palace Theater. In 1906, however, it was an engagement at the Casino International de Figueira da Foz, located in Foz, a seaside city several hundred kilometers north of Lisbon. This was Argentina’s first official international tour.

From Lisbon, Argentina decided to make her way to Paris, where flamenco dancers had toured since the turn of the century. The Parisian craze for Spanish flamenco dance and music had initiated a Spanish vogue so popular that the singing cafés, as well as the music halls and variety theaters, contracted hundreds of Spanish dancers to play the “ethnic” act in any number of variety lineups.

In the winter of 1907, Argentina debuted on screen as a solo dancer and castanet-player in the lost film El Brillante de Cartagena, and began to be called “La Bella Argentina” by the Spanish press.

Following her first and only cinematic work (released in 1908) Argentina returned to her base in Madrid, touring the surrounding cities of Oviedo, Lisbon, Valladolid, and Murcia. She premiered on 15 August at Madrid’s Teatro Principe Alfonso and on 15 September at the Salón Madrid. Argentina was now performing so much that her name began to appear frequently in the Spanish press. The publication La tierra cartagenera wrote at the time: “The notable artist of the Spanish dance, ‘the beautiful Argentina,’ appeared last night in this lucky theater, and just as in all the tours she has made here, the ‘queen of the farruca’ [a traditionally male flamenco dance] attained great success.”57 On 12 July, Argentina debuted at Madrid’s great salons, the Salón Novelty and Gran Café Teatro de Madrid.

By 1909, Argentina added every major variety theater in Madrid to her list of performance venues. “La Argentina” had now become associated with the Salón Artístico, the Pabellón Fino, and the Cine Martin, the most famous dance and film variety halls. The Madrid public was now accustomed to reading about her nightly appearances the following day in A.B.C., Nuevo mundo, and La unión.

Argentina also expanded her Spanish tours to include Andalusia. She performed on the Costa Brava at Malaga’s Salón Moderno, and in Vigo at the Salón Artístico, returning to Madrid to play the famous Royal-Kursaal before embarking once again for France. The Malaguenen daily, La unión mercantil, featured daily reviews of January performances, describing her as “master of the farruca,” as well as “beautiful and handsome in body and voice, with such original grace that she holds no rivals.” The paper went on to point out that “in the Garrotín, she reveals herself as maestra, injecting the Indian origins into her dances, so that we may firmly understand” them.58

Argentina, traveling once again with her mother as chaperone, arrived in Paris at the end of the summer of 1910. She immediately found work in the chorus of the famous café chantant, the Jardin de Paris. By the summer of 1910, after enormous personal success and added flamenco training throughout Spain, Argentina was given a small role in a new Spanish musical. According to the Spanish press, Argentina’s youthful energy communicated her charisma to audiences. Now, she employed not only her classical experience on the opera stage, but her flamenco technique on the tablao stage. Due to a bad Montevidean review that characterized her singing as shrill, and unsonorous, Argentina stopped singing during solo dances, which numbered twenty-six in a single evening by the year 1915. Her performance became, therefore, intensely physical and it is no wonder that Argentina’s attention to decor would help fill the dramatic gap left after she removed vocal accompaniment. Her multiple dance techniques and her added years of castanet-playing were about to launch her to stardom.

She was hired later in 1910 by Halévy, Jouillot, and Mareil, directors of a variety bill, composed mostly of Valverde compositions. Argentina performed in a short operetta on the bill and was a success. The show was performed at Toulouse-Lautrec’s Montmartre music hall, the Moulin Rouge. Because they had seen Argentina’s 1906 appearance at the Jardin de Paris, the show’s directors decided to give the young performer a small but noticeable part. She danced alongside Antonio el de Bilbao and the celebrated Mojigango.

Although only one of fifty dancers in the final number, her interpretation of the tauromachic rites enacted in the Moorish arena launched her to fame, and she began to be noticed by the French press. Later on, she was to dance a short solo in the show on a theme composed by Quiñito Valverde, a popular composer known as the Spanish Offenbach. Valverde’s most dramatic dance number in the show, however, was La corrida, the story of a bullfight in which the matador hunts and kills his prey. When Argentina heard it in rehearsal, she immediately recognized the dramatic power of the dance. She asked the directors if she could both choreograph and perform it. La corrida became her signature piece and remained in her repertory of short solo dances until the day she died.

In it, Argentina was to enact both the predatory motion of the bull and the sadistic plunging of knives into the bull’s back by the banderillos. Her effortless control and machine-gun fire-like stamping on the floor, executed as the bull falls to the ground, showed the banderillos to be the sadistic slayers they are.59 In the 28 September issue of the theatrical review Comoedia, the critic M. Emery noted that “the enthusiasm, the adoration of the audience fell, above all, on this small dancer who made her debut on the Parisian stage, if I am correct, yesterday afternoon…. This wonderful Argentina will be one of our idols tomorrow.”60 Monsieur Emery’s intuition proved correct.

After completing the run of the show, Argentina was once again contracted by the music hall impresarios. This time, she was to perform a solo of her own making, set within a new Valverde extravaganza. An operetta in two acts and four scenes, The Rose of Granada, with costumes by the famous Madame Hannaux, became an instant success and ran for a year. Filled with Fredaff’s acrobatic jumps and falls, La Rose de Grenade told an intensely funny tale, a farcical portrayal of toreros, Gypsies, serenos (night-watchmen), and serenades beneath balcony windows, and dancers who ended in proper flamenco desplante (defiant), replete with “olés!”

The Rose of Granada tells the story of a young virgin, Rosita, played by a very blond French music hall star, Mariette Sully. Rosita, although betrothed by her mother to the Marquis de Vera-Cruz, falls tragically in love with a matador who leaves her for a pretty young Granadan dancer.61 Upon hearing the news of the matador’s other love, Rosita falls to the ground in fits of rage and anguish.

The musical was first performed in 1911 in Brussels at the Théâtre des Variétées, beginning a yearlong run in February 1912 at the Olympia Theater in Paris. On a theatrical level, the story was unsophisticated. But as an entertainment extravaganza, which was the purpose intended by its producers, it was a box-office triumph.62 “The great success of this musical,” said Comoedia Illustré, “goes to the dance, which was admirably executed by an extraordinary trio, including Mado Minty, a supple and beautiful mime.” Rafael Pagan, “consecrated after her long run at the Odéon in the ‘Jardins de Murcie,’ stamped out the flamenco rhythms with marvelous traditionality.” Finally, “the Spanish dancer, Argentina, vibrating and voluptuous, her flashy heels covering the musical scales, handled her castanets with sensual pleasure which … astonished” her audience.63 Her charisma and talent were now confirmed by the French popular press and read by “le tout Paris,” the smart set of Paris.64

By 1916, in her first North American performance, Argentina’s rhythmic ability was also confirmed by the New York press. About La corrida, one journalist remarked that “Madame Argentina’s synthesis of the bullfight is one of the most spectacular and picturesque. You will find in it the festive and spectacular side: the horses, the banderillos. It is no sketch; rather, it is a synthesis, scientifically deduced from the general movement of the bullfight.”65

Guy de Pourtalès’ description of La corrida bears witness to the young choreographer’s second essential feature: her fervent nationalism. Evident in this sketch was Argentina’s use of the archetypal Spanish theme, death. Pourtales reiterates poet García Lorca’s oft-quoted lecture on the play and the theory of duende, in which he says that Spain is “a nation of death, a nation open to death.”66 It was Argentina who capitalized on the imagery of the bullfight as representative of Spanish culture. In Lorca’s words, “the popular triumph of Spanish death” captured in “the supremely civilized festival of the bullfight” symbolized the “final, metallic value in death” worshiped by Castilian and Andalusian culture.67 It was in this, Argentina’s first Parisian choreographic success, that she began to discover the importance of an aesthetic representation of Spanish nationalism through dance. From 1912 to 1936, Argentina would follow the nationalist artistic pulse of García Lorca, Manuel de Falla and representatives of the Generations of ’98 and ’27. Lorca discovered an artistic supporter and mirror in Argentina. “All the classical dances of this great artist,” he said, “are her unique signature, at the same time that they are the signature of her country, of my country.”68

The great flamencologist and bailaor, Fernando Rodriguez el de Triana, reinforced Lorca’s words in 1957, when he dedicated his famous work on the artists of the flamenco genre to Argentina. “Antonia Mercé, La Argentina,” he said, “is the messenger dove of flamenco art; the best bailaora de tablao. This is her genius, that Antonia danced as classically and as flamenco-like as the masters and that these masters and professional jondo dancers were enthralled by her performance.”69 Argentina, in the early stages of her career, had become a star who, in her aesthetic emphasis, provoked any Spaniard to reflect upon his country and, perhaps, about the time through which he had lived.

By 1912, Argentina had earned her place alongside Pastora Imperio, Fornarina, Candelaria Medina, and La Monteverde. Her variation on the Gypsy flamenco technique—the formulation of her own dance language on Spanish themes, never repeated by anyone else—became the primary tool by which Argentina would conquer Parisian audiences.

Costume for Triana designed by Néstor de la Torre. Collection Paravicini.

Costume for Triana designed by Néstor de la Torre. Collection Paravicini.

Costume for Tango Andaluz. Collection Cátedra de Flamencología, Juan de la Plata, curator, Jerez de la Frontera.

Costume for Danza de los Ojos Verdes. Collection Marieemma.

Costume for Bolero Clásico. Collection Institut del Teatre, Barcelona.

Costume for La Cariñosa. Collection Mme. Gaube-Bertin.

Costume for La Charrada. Collection Mariemma.

Costume for Lagarterana. Collection Paravicini.